About the author

Anne Kirker is an independent art consultant, curator and writer. More about Anne Kirker

Collecting works on paper in Australia: specialisation at risk?

by Anne Kirker

Numerically, works on paper form the major part of permanent collections in Australian art museums. [1] They have traditionally been considered the linchpin for educating audiences in the histories of art. In the 1960s and 1970s there was a push to establish specific departments dedicated to them and a drive for curatorial expertise in such media-specific areas. This produced finely honed connoisseurship and notable acquisitions, leading to exhibitions of discernment and depth. This practice of connoisseurship was a key ingredient in safeguarding the integrity of an art museum’s collection. However, the past decade has witnessed, especially in smaller institutions, the eradication of barriers between media. This partly reflects the impact of postmodernism in the approach to interpreting collections, where the production of meaning is paramount rather than an emphasis on contextualising art works within known frameworks of aesthetic excellence, chronological ordering and links with art history. [2]

There have been notable gains as custodians with overarching collection responsibilities bring fresh insights into the realm of works on paper. Often more heterogeneous explorations – combining paintings, three-dimensional works, film and works on paper – inspire connections that may not readily be made if the objects were isolated from each other. The expansion in understanding of how art can be articulated for contemporary audiences means also that medium-specific exhibitions from permanent collections now freely traverse an identified subject, placing prints from the 1990s, for instance, with their thematic counterparts from earlier periods.

A number of conundrums remain. One is that curators, unless they are employed in large institutions where it is impractical to disband or disperse comprehensive holdings formed under media classifications, are unlikely to be specifically trained in all fields under their care. [3] This can result in errors of judgement associated with appraisal of artworks and collection acquisitions. Another potential loss is the particular passion that specialists bring to a field – say, printmaking, – that, if denied recognition, can leave it on the sidelines.

A further development has been the corralling of modernist or small-scale works of photography, prints and drawings into a medium-specific department, while progressive post-1980s works are relegated to the general area of contemporary art. While we may rejoice in viewing displays of commanding series and installation-scale works on paper, this process is fraught with discrimination as more discrete statements are once more relegated to less frequented display spaces, or to the darkness of a Solander box.

With the rapid growth and popularity of art museums in the 1990s, visible through building programs and increased budgets for marketing, development and public programs, what tends to be hidden is the diminution of the traditional role of curator and the bond that person had with the collection.

Curators in the 1980s were confident of their brief: to have sole leadership in the care, acquisition, selection, research, display, publication and promotion of works on paper under their custodianship. These print curators were prized authorities in their field, and persons to be consulted for accurate and unquestionably sound appraisals and advice.

In the 1970s and 1980s specialist curators were understood to be, along with their fellow curators, the linchpins for defining exhibitions and education according to a clearly defined mission statement.

In opening up to fairer representation and widening of geographical bases for acknowledgement, the study of visual arts today has downplayed the fundamental imperative of curators to appreciate how a work is executed, when it is likely to have been made, and the circumstances surrounding its creation. [4] This disruption to tradition has provocatively ‘opened up’ art history. Yet at the same time it has tended to undermine the science of tracing provenance, of identifying date according to type of signature, paper and other materials used, the importance of language skills for research, knowledge of key reference texts, and of personnel equipped to assist in a work’s authentication. In short, connoisseurship has been dismissed as a preoccupation best suited to auction houses. The word ‘connoisseur’, in fact, is hardly used in the early 2000s.

While few would not welcome the stretching of art history as it has unfolded since the 1980s, what has inevitably been lost is the fact that most works of art have a genealogy and infrastructure of their own. Prints, for example have their own highly specific history, as does photography. [5] This in no way diminishes their valuable usage in mixed-media exhibitions and discursively driven projects.

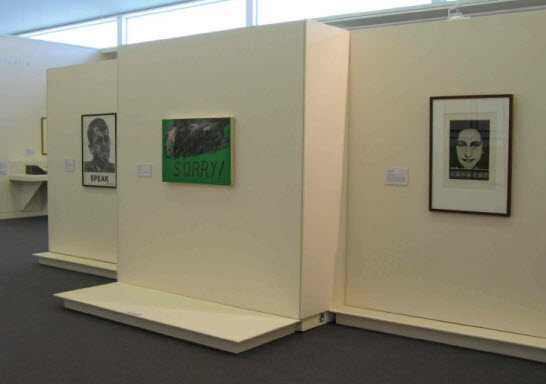

Installation view of an aspect of the cross-media exhibition Masters of Emotion: Exploring the Emotions from the Old Masters to the Present curated by Irena Zdanowicz for the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery 20 April – 24 June 2007. The photograph shows the juxtaposition of an etching ('Seven' 1974) by Bea Maddock with a painting ('Sorry' 1982) by Linda Marrinon. Photo: courtesy of Morning Peninsula Regional Gallery.

By the early 2000s, the very term ‘curator’ has shifted in emphasis from being a noun to being a verb, an active and engaging force. An individual ‘curates’ an exhibition, for example, rather than being ‘a curator’ of a collection. The curator of an exhibition no longer has the luxury of sole responsibility for the initiation, development and presentation of the show, but is usually surrounded by a team of people with an equal stake in the event. These ‘stakeholders’ are also highly trained within their particular spheres, whether it be exhibition design, promotion or education.

In this environment, the curator may be hired as a freelance employee rather than one located within the institution who, over a period of time, has built up a substantial knowledge of the institution and all its collections. The contemporary focus in art museums tends to be on the production of highly visible, entertaining events that are nevertheless educational and which may demonstrate in-depth research. Inevitably they attract the largest resources. They are intended for a broadly based constituency, but with specific programs tailored for groups such as children or senior citizens.

However, in larger art museums with in-depth collections, traditional curatorial standards are most likely to be maintained as a desirable aspect of the institution’s corporate identity. The National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in Canberra is an obvious case in point. Specialist curators have largely been maintained there to ensure the care and maintain the scope of the collection, including acquisition, preservation and access, interpretation and exhibition, research and publication. The sheer quantity of objects owned by the institution, and the desire of most NGA directors to focus on maintaining high levels of scholarship, are the reasons why within culturally determined departments there are curators who are trained in appreciating prints, and/or drawings and photographs. Furthermore, the NGA funds research internships and regular symposia to ensure print practice and scholarship is acknowledged and maintained in Australia.

'The Print Room (dedicated to Ursula Hoff) at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne 2004', Photo: courtesy of Alisa Bunbury and the National Gallery of Victoria.

As a result of the munificence of the 1904 Felton Bequest, the Print Room holdings at the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) boast one of Australia’s most distinguished International (mainly European) works on paper collections. At the same time it has assiduously collected Australian material. The distinguished European émigré, Dr Ursula Hoff, steered the Print Room into its pre-eminent position in Australia at the St Kilda Road site. This model of a discrete department with viewing and research facilities was subsequently adopted throughout Australia. In Adelaide this model continues into the twenty-first century. At the Art Gallery of South Australia, there is one department responsible for 23,000 prints, drawings and photographs covering all schools, with trained staff – at least one formerly from the NGV – following the high standards of scholarship set by Hoff and the staff she mentored in Melbourne.

In contrast, while works on paper continue to be a significant area of collecting for the Queensland Art Gallery (QAG), the approximately 6250 works on paper are currently spread throughout the curatorial departments of Australian Art, Asian and Pacific Art, and International Art and Cinema. An expertise in photography and printmaking as discrete areas of specialisation may still be present, yet overarching briefs subsume it. Sometimes the art works themselves dictate this. For instance, in 1995–97 a large collection of Fluxus works entered the collection, courtesy of Francesco Conz in Verona. Practically all of these items defied the usual taxonomies of classification.

The collecting of works on paper for art museums in Australasia is an evolving phenomenon. This is subject to a number of contexts, including the physical, economic, ethical, and aesthetic as well as dramatic shifts in ideology, especially as they pertain to the function of art museums and the way in which art history has been rearticulated. Accordingly, the role of collection curators has changed significantly since the 1980s as their former autonomy within the institution has been diminished (especially in smaller institutions), and their specialist expertise has often been less valued.

A challenge for art museums in the coming years is to recognise the value of the integrity of their collections, and of congruent curatorial advice regarding exhibitions and publications. Core curatorial duties remain just as essential when changing priorities are facilitating the demonstration of the joy in collecting works on paper to larger audiences than ever. Through stimulating exhibitions and allied events, and all manner of publications (paper and online), their power and relevancy within the scope of the past and of art’s expanded role can be emphasised.

Footnotes

1 If this essay tends to use the print as prime example of the area of ‘works on paper’, it is because such collections began in the early development of collections and have become the mainstay of the print room in major public galleries in Australia. Perceived from the 1960s and 1970s as a democratic art form, being relatively inexpensive, the print was also an educational means to promote an appetite for and understanding of art in general.

2 Konrad Oberhuber, former director of the Albertina in Vienna, one of the world’s premier museums for prints and drawings, wrote that in the late twentieth century there were two kinds of art museums: the museum of ‘information’ and the museum of ‘experience’; the J Paul Getty Museum being an example of the former and Guggenheim Museum Bilbao of the latter. See Oberhuber, ‘Thoughts Regarding the Millennium’, Apollo, January 2000), pp. 19–23.

3 In fact, in some cases where medium-specific curators are no longer at hand, as in the case of the Queensland Art Gallery, it is more likely that paper conservators would be consulting such texts and providing the relevant cataloguer with their opinions. Unlike curators, conservators tend to have job descriptions that are more contained, with functions that are more readily identified.

4 See, for instance the provocative article by Charles Green, ‘Art as Printmaking: the deterritorialised print, Art Monthly Australia, No. 58, April 1993.

5 It is important to note the numbers of works involved. For instance, the AGNSW’s Australian works on paper collections, prints and drawings number 9798 Australian works, of which 4309 are prints. When including those administered by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Contemporary Australian art departments, these figures go up to 10,308 works on paper, incorporating 4653 prints.

Anne Kirker is an independent art consultant, curator and writer.

Cite as: Anne Kirker, 2011, 'Collecting works on paper in Australia: specialisation at risk?', in Understanding Museums: Australian Museums and Museology, Des Griffin and Leon Paroissien (eds), National Museum of Australia, published online at nma.gov.au/research/understanding-museums/AKirker_2011.html ISBN 978-1-876944-92-6