West Arnhem Land

The Aboriginal people of the Cobourg Peninsula, west Arnhem Land, experienced two failed attempts by the British to establish military outposts in their country. During this time, cultural material and human remains were taken to London.

Explore the ways that Cobourg Peninsula Aboriginal people reflect on this time.

Setting the scene

John Bugi Bugi, Muran man, 2015:

Every square inch of Cobourg … indeed every square inch of Australia had a name, and a use, and belonged to somebody.

Carol Christophersen, Muran woman, 2014:

People today can look at those objects and say I know those objects, I know how they are made, I remember my grandmother showed me, I remember that material, I know how to find it, I know what tree it is, I know where that tree is — and that’s a very powerful message in that this knowledge is still here ... It’s not forgotten.

The first peoples of the Cobourg Peninsula, west Arnhem Land, have lived and thrived for millennia in their country of beaches, wetlands, grasslands and forest.

In the early 19th century they witnessed two unsuccessful attempts to establish a British colony in northern Australia: first at Fort Wellington, which lasted only two years, and at Port Essington, which failed in 1849 after 11 years.

Don Christophersen, Muran man, 2014:

1840s — it doesn’t seem like long ago but people’s world changed considerably once they met the first British that came here, and their world would change, their lives would change.

Artawirr (didgeridoo)

This bamboo didgeridoo is the oldest known didgeridoo in existence. It was most likely collected by a British ship visiting Port Essington.

Carol Christophersen, Muran woman, 2014:

These objects ... are part of a collection that the British made during their time here at Port Essington ... They also represent for us a time when the human remains were collected, not only from here in Port Essington ... but all around Australia.

Don Christophersen, Muran man, 2014:

There is a yet unspoken connection between the collection of artefacts and the collection of human remains during the English occupation … This is a significant element of the encounters then and the encounters now, between people and institutions and how to move on from the past … [We] do want the whole story to be told, and for this exhibition not to erase from the records … this disturbing aspect of our shared history.

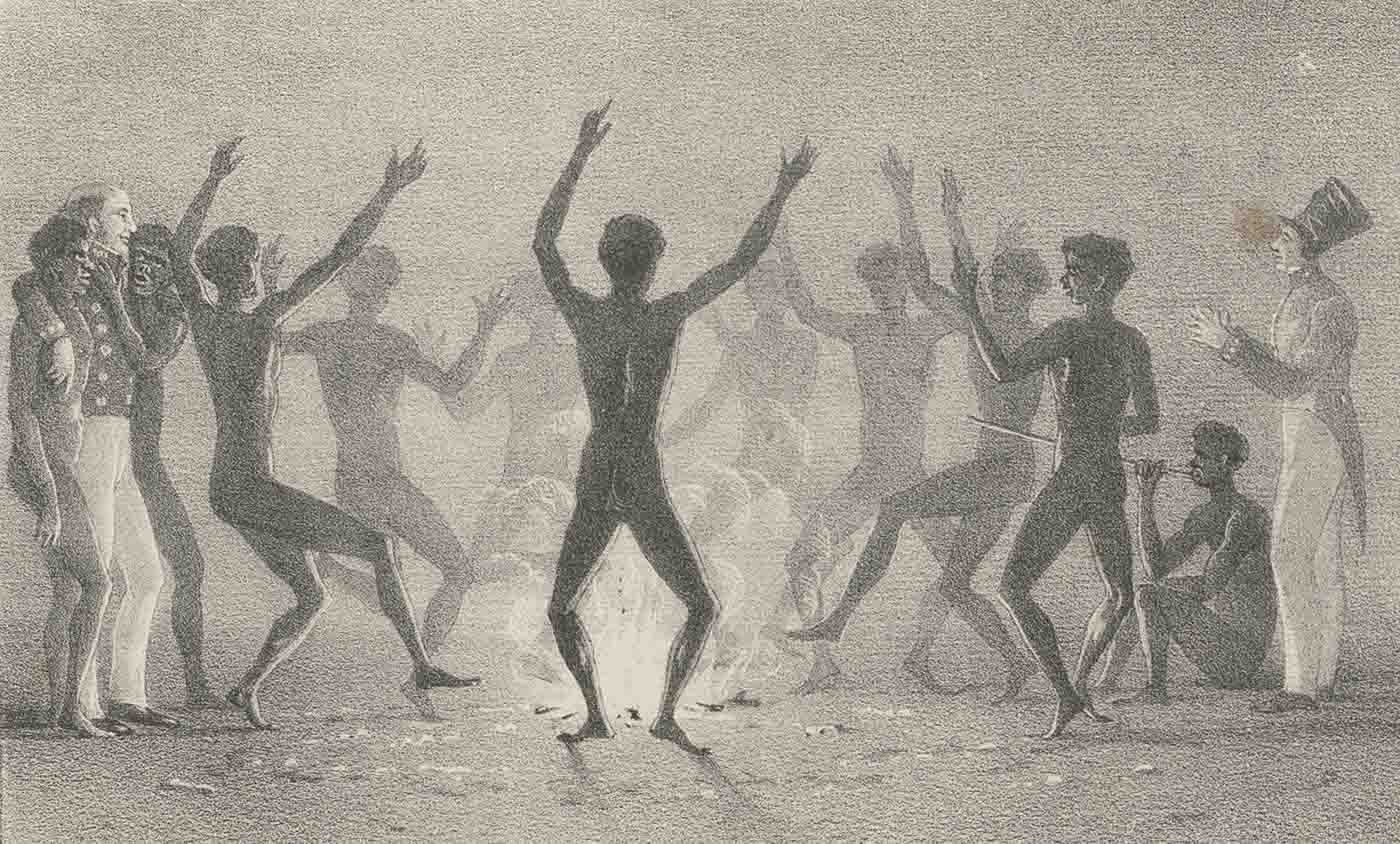

Dance of the Aborigines

Today didgeridoos are rarely made from bamboo, but Aboriginal people from northern Australia sometimes still call didgeridoos ‘bamboo’. In the image above, the man seated at right is playing an artawirr.

Don Christophersen, Muran man, 2014:

I guess what stunned me was to find that etching at Fort Wellington of Commandant Collet Barker with his arms around two Aboriginal men. And there’s a group of men performing a corroboree. There’s a man playing a didgeridoo, and the didgeridoo looks very long and slender like a vacuum cleaner tube, but it’s made out of bamboo … You get a totally different sound from bamboo … You can also make them out of pandanus … I’ve seen photographs in the 1930s and Aboriginal people were still using bamboo.

Bark painting

British ships visiting Port Essington often collected objects which were later acquired by the British Museum. The oldest Aboriginal bark paintings known to exist come from Port Essington. These objects still have meaning for the people of the Cobourg Peninsula today.

Carol Christophersen, Muran woman, 2014:

The Encounters project is really about people. There’s no other way round it. Yes, the British

have got these objects and they want to show us photographs and they want to put some in the

museum, but it is about the people ... Who were these people? Who are these people today?

Well, we are these people ...Without people, they’re just objects. Without the stories, without the knowledge, they’re still just

objects ... For the people of west Arnhem region, these objects show us a glimpse into the past,

of the technology, the creativity and the skill ... our history of the people that came before us.

And it reminds us of how much we still know, of how much we retain — the knowledge we have,

how proud we are.

Marruny (basket)

Ningoldie Blyth, Minaga elder, 2015:

[Marruny] were really important because they could carry water … Every billabong we would fill it up again, walking for days. We would put honey and water … stir it up and drink it to keep us kids going.

Marcus Dempsey, Ulbu man, 2015:

When I saw it, it reminds of me of granddad making it.

Small palm-leaf basket

This basket was made in response to the basket collected from from west Arnhem Land in 1911–12.

Large palm-leaf basket

Marcus Dempsey, Ulbu man, 2014:

That [basket] was from the 1800s. Now, in the new millennium, Nana is showing me how to make [a new one]. I love helping Nana because she is the last one for us … I’m proud of her teaching me, so I can teach my mob.

Video stories

Learn about making a water basket

Watch this video of Cobourg Peninsula Aboriginal people making a water basket.

Activity: This film shows how knowledge and techniques needed to create a basket are passed from generation to generation. Why do you think this so important from a cultural perspective?

What do you know about Port Essington?

More activities

The removal of Indigenous human remains from Australia is an issue of immense significance. Carol Christophersen, Muran woman, 2014:

These objects ... are part of a collection that the British made during their time here at Port Essington ... They also represent for us a time when the human remains were collected, not only from here in Port Essington ... but all around Australia.

Don Christophersen, Muran man, 2014:

There is a yet unspoken connection between the collection of artefacts and the collection of human remains during the English occupation … This is a significant element of the encounters then and the encounters now, between people and institutions and how to move on from the past … [We] do want the whole story to be told, and for this exhibition not to erase from the records … this disturbing aspect of our shared history.

Discuss some of the reasons why human remains were collected in the first place, and why their return is considered so important for people today.

Explore more on Community stories