Yirandali country

Yirandali country in central north Queensland attracted pastoralists keen to exploit the grassy plains.

Explore how Yirandali people, including Dalleburra elder Ko-Bro, and pastoralists interacted, and how people today reflect on those times.

Setting the scene

The grass-covered plains that dominate the country of the Yirandali-speaking Dalleburra people made it highly desirable to pastoralists. Robert Christison established Lammermoor station there in 1863.

The Dalleburra people formed relatively good relations with Christison, in contrast to the violence dealt by settlers on neighbouring stations.

Christison’s daughter, Mary Montgomerie Bennett, in her 1927 book, Christison of Lammermoor, recalls her father declaring to Ko-Bro:

You and me sit down two fellow messmate. Country belonging to you: sheep belonging to me.

Although the establishment of Lammermoor progressed without the violence that accompanied the settlement of other regions, Christison’s relationship with the Yirandali was one based on the exertion of power.

Lee Burgess, Yirandali man, 2015:

When they say Christison ‘first negotiated’ with Ko-Bro, what they’re not saying is that Christison tied Ko-Bro to a post, and talked to him over a matter of weeks. He fed him and gave him water … I wouldn’t have made friends with someone who’d done that to me.

Christison differed from many other pastoralists in that he allowed and encouraged Yirandali people access to their country.

When they sold Lammermoor in 1910, the Christisons sought to secure Dalleburra people’s access to the land. Robert Christison asserted that he would ‘not discuss anything until their right to remain on the station as their home is settled’.

Despite these intentions, Dalleburra people were moved off their country, some ending up on reserves on Palm Island, and at Barambah/Cherbourg.

Dalleburra people

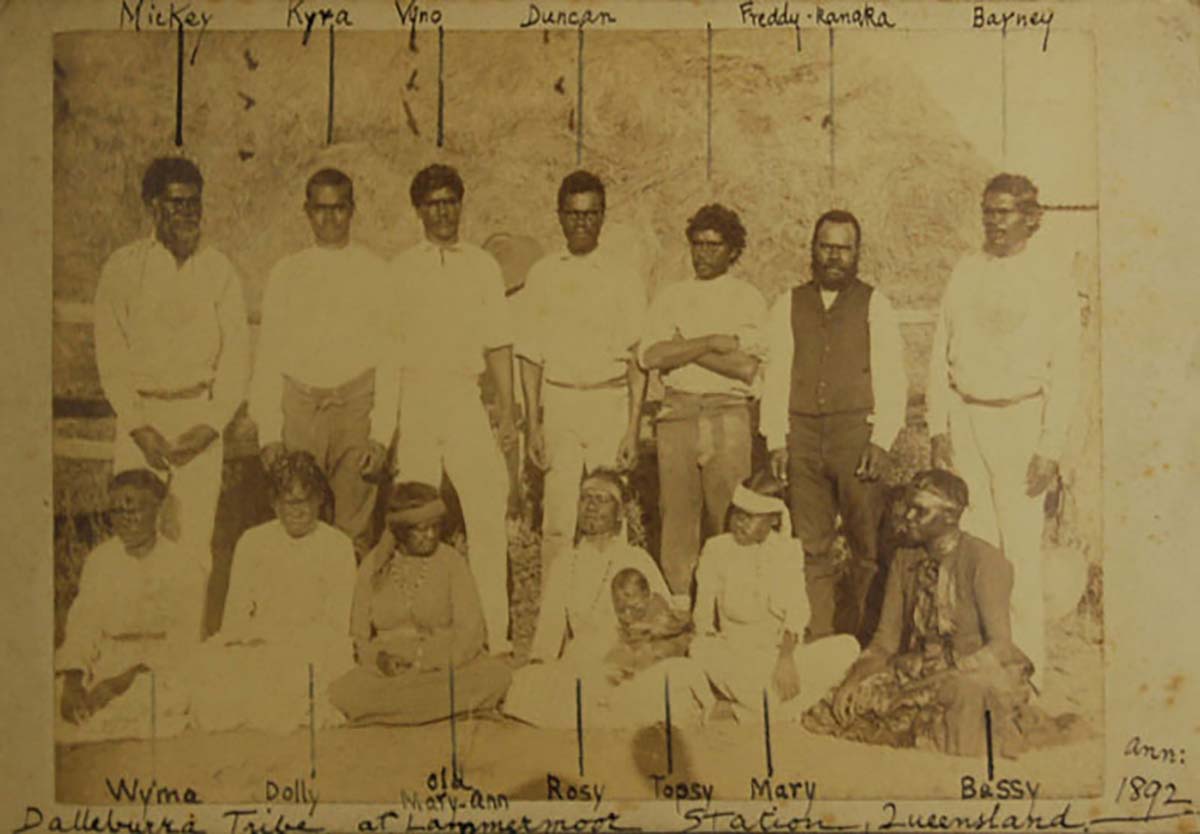

Before they were forcibly removed from their country, Christison took a keen interest in the Yirandali, collecting cultural artefacts which he later donated to the British Museum. His wife, Mary, took numerous photographs of the Yirandali.

Christison’s daughter Mary Montgomerie Bennett, who became a writer and activist for Aboriginal rights, captioned the photographs and later gave these photos and other objects to the British Museum.

These objects and images are a link to a time when the Yirandali practised their culture on their own country. Today, although still denied access to parts of their homeland, they continue to practice their culture through hunting, fishing, art and storytelling.

Jeffery Lammermoor, Yirandali man, 2015:

I know how lucky we are — my ancestors were named in their photos. It shows there was a good relationship back then. Not anymore. We still go back to Lammermoor station but we stay away from the homestead. We go down to the camping grounds and visit the burial sites. They are not marked, but we know them.

Message stick

Christison collected a number of carved message sticks given to the family by Dalleburra people. The markings on them are not a written language, the actual message being delivered by the holder of the stick.

Christison wrote down the messages he received. The message associated with this stick, for example, was recorded by Christison as ‘Mickey want ’em two fellow coat, hat and shirt’. These sticks give an insight into the relationship between Dalleburra station workers and Christison — here Mickey is asking for more clothes.

Just Want to Look Good necklace

Today, Yirandali culture is expressed through the creation of art.

Malcolm ‘Mickie’ Smith, Yirandali and Wanamara man, 2015:

The ancestors made jewellery with what resources they had. I make my jewellery out of old computers.

Video stories

Learn about making a greenhide rope

Watch this video where Yirandali man Fred Hill talks about growing up on stations in western Queensland.

Activity: Have a classroom discussion about what age children left school? Why did they leave school? What did they do when they left? Interview a grandparent or older friend about their school experience. What age did they leave? What hopes and expectations did they have? What did they end up doing?

What do you know about Lammermoor station?

More activities

Yirandali people used message sticks as a way to communicate. Create a poster, or plan a classroom presentation, on how communication devices have changed over the past few hundred years.

Robert Christison allowed Yirandali people to camp on Lammermoor station, whereas other station owners refused entry to local Aboriginal people. Carefully read the information above then discuss what kind of relationship Christison had with the Yirandali people.

Malcolm ‘Mickie’ Smith makes jewellery out of old computers. Design and make your own jewellery, using something that has been discarded.

Explore more on Community stories