Tasmanian Aboriginal country

Tasmanian Aborigines continue to celebrate their culture and spirituality, despite the actions of British colonial authorities who exiled many of their people, including leader Mannalagenna, to Flinders Island.

Setting the scene

Theresa Sainty, pakana (Tasmanian Aborigine), 2014:

[People say,] oh ... they’ve lost so much. But I think … hang on a minute. Isn’t it wonderful that we have so much culture that we have retained. To be taken from country … taken to those islands where you’ve got nowhere to go — prisoners almost … And yet, they [our ancestors] made sure information is passed down through their families. Against all odds.

Mary Ann Friend, visitor to Hobart, 1830:

The [British] inhabitants are carrying on a war of extermination with the natives who are destroyed without mercy wherever they are met.

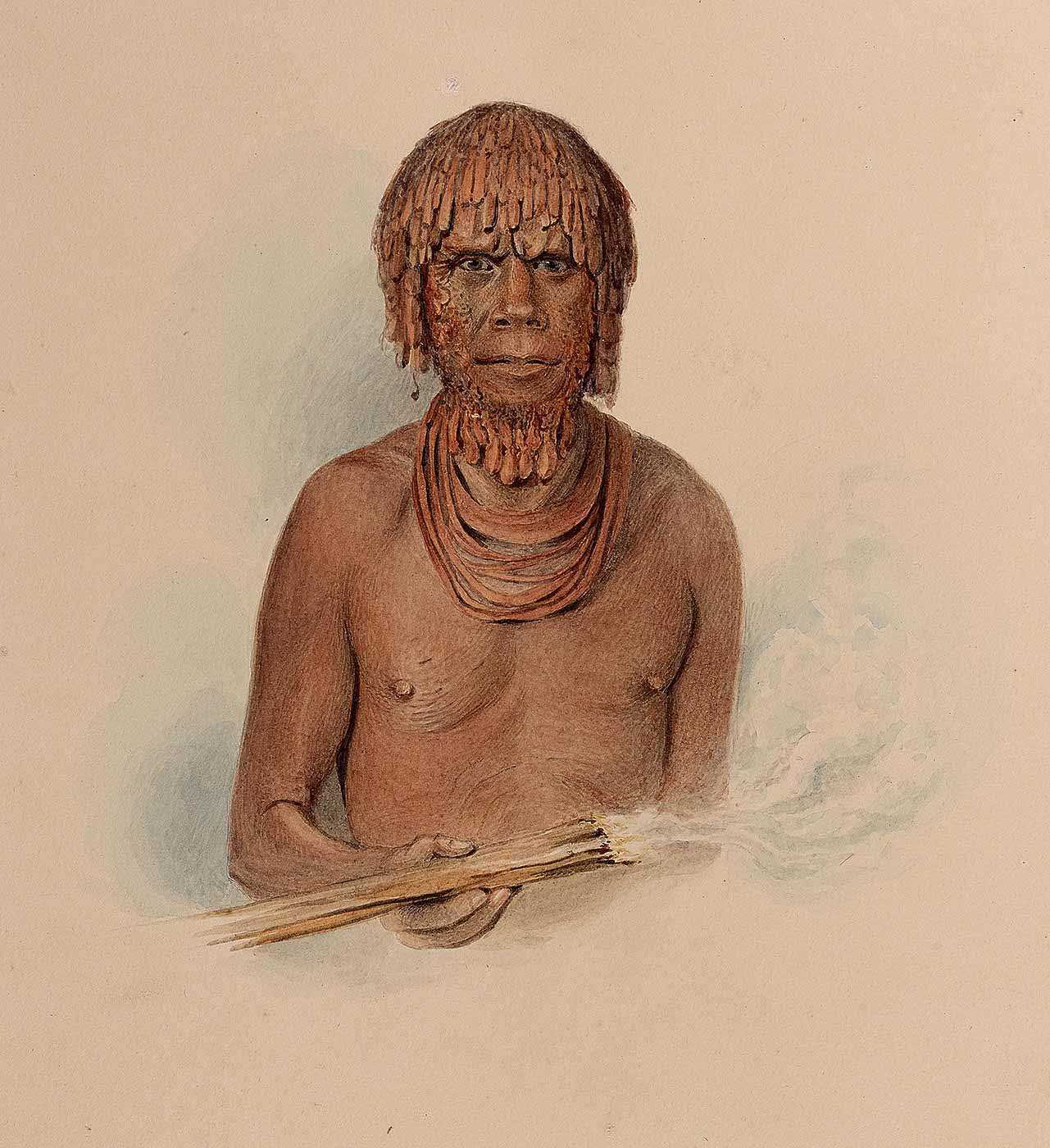

Manalargenna

In the early 1830s authorities exiled 134 Tasmanian Aborigines to Wybalenna on Flinders Island in Bass Strait, about 50 kilometres north of the Tasmanian mainland. The people worked to keep their culture strong, but their sense of loss was profound.

Mannalargenna was leader of the Cape Portland people from north-east Tasmania. He had negotiated with George Augustus Robinson, the Protector of Aborigines, for his people to remain in their country in return for assisting Robinson.

In about 1834 Mannalargenna and his people were exiled to Flinders Island. Although Mannalargenna had kept his word, Robinson had not.

Aunty Patsy Cameron, Tasmanian Aboriginal elder, 2014:

On the boat taking him away, Mannalargenna paced the deck like an emperor … looking through his spyglass at his country for the last time. Just off Flinders Island he cut his beard and his ochred hair, which showed his status as a bungana, a leader of his people ... Within five weeks he was dead.

Mannalargenna is recognised as the ancestor of many Aboriginal people today.

Clyde Mansell, palawa elder, 2014:

The minute I look at that [portrait of Mannalargenna] I immediately within myself reaffirm who I am.

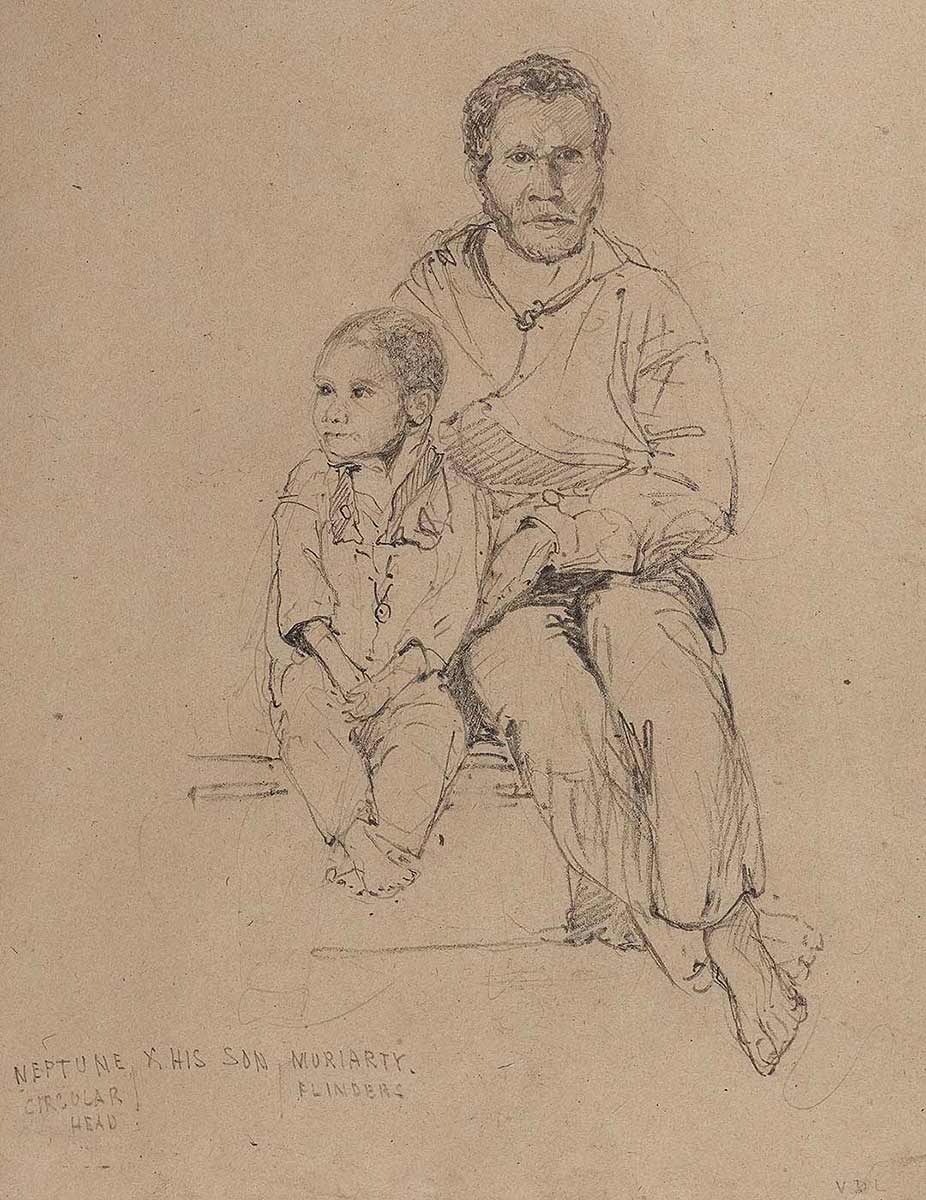

Neptune [Merape] & Moriarty

Artist John Skinner Prout created a series of intimate portraits in early 1845 at Wybalenna Aboriginal Station on Flinders Island. Merape (meaning 'hailstones') was from Circular Head in north-west Tasmania.

Enduring poor living conditions, disease and neglect, many at Wybalenna sickened and died. In 1846 people from Wybalenna petitioned Queen Victoria about the appalling conditions there.

By 1847 when Wybalenna was abandoned, only 47 people remained.

Leonie Dickson, Tasmanian Aboriginal elder, 2014:

At Wybalenna they were so homesick they used to climb to the top of the hill and think that they could sort of fly off and … see Tasmania in the distance.

For Tasmanian Aborigines today, there is both strength and sorrow in remembering this time.

Greg Lehman, palawa, descendant of trawulwuy people, 2014:

These portraits … are a testament to the strength, not just of the Aboriginal spirit but also the human spirit, which allows people to survive these sort of things, whether they occur in Van Diemen’s Land in the 1830s or whether they occur in Europe in the 1930s, only a hundred years later.

Shell necklace

Dorothy Murray, Tasmanian Aboriginal elder, 2014:

When I got to about eight years of age I learned to do my culture then, my shell stringing, and going with the elders to the beaches ... I used to love listening to them talk, collecting shells.

Tasmanian Aborigines have always made shell necklaces. Shells with holes pierced for threading have been found dating to around 2000 years ago.

Women pierced shells with tools of kangaroo bone, then threaded them onto sinew or fibre. Before threading, shells were smoked, then rubbed to reveal their pearly surface, and polished with oil.

Missionary James Backhouse wrote in A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies, 1843:

After receiving a few waddies [clubs] and some shell necklaces from the natives and making them presents in return, we took leave of them.

Coiled basket

A group of Tasmanian Aboriginal women came together from 2006 to 2009 to make baskets, including the one pictured above, as a way of connecting with baskets made by their ancestors.

The project was called tayenebe, meaning ‘exchange’. Women learnt the skills of basket-making and gained an understanding of bull-kelp and other plants that were used to make the older baskets.

Leonie Dickson, Tasmanian Aboriginal elder, 2014:

My descendants will say ... my great, great, great, great grandmother — she made this basket … A Tasmanian Aboriginal woman made this … So many years down the track we’re still going to be recognised.

Video stories

Reflect on a broken promise

Watch this video where Tasmanian Aboriginal elder Aunty Patsy Cameron says: ‘On the boat taking him away, Mannalargenna paced the deck like an emperor … looking through his spyglass at his country for the last time ... Within five weeks he was dead.’

Activity: Are there aspects of this story that you find disturbing or surprising? Make a note of one new thing you learn and one question you have. Share these responses with your class.

What do you know about Flinders Island?

More activities

Activity:

Have a class discussion about a body of knowledge or skill that has been passed down to you, inspired by this quote from Tasmanian Aboriginal elder Leonie Dickson, 2014:

My descendants will say … my great, great, great, great, grandmother — she made this basket … A Tasmanian Aboriginal woman made this … So many years down the track we’re still going to be recognised.

What is the body of knowledge or skill? How did you learn it? How would you teach it to someone else?

Activity:

Learn about the tayenebe project on the Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery website and discuss why you think it is important for Tasmanian Aboriginal women to rediscover and connect with their cultural heritage.

- Download Download the tayenebe education resource2.2 mb pdf [ PDF | 2.2 mb ]

Explore more on Community stories