Erub (Darnley Island)

The sea has always had great significance for the people on the island of Erub.

Explore how this connection to the sea is reflected in their cultural heritage, and how it continues to inspire artists today.

Setting the scene

Bully Saylor, Erub elder, 2014:

Tell the stories about the older times so that [people] can respect the way we lived in the past, all the way to today.

Salt water runs in the veins of Islanders like Bully Saylor, who has an intimate knowledge of the reefs and waters around Erub (Darnley Island), in the Eastern Islands of the Torres Strait. He was one of the people who worked to achieve the 2010 Federal Court decision to recognise native title in the seas of the Torres Strait.

Located on one of the sea routes used by European ships to reach new colonies in eastern Australia, Erub was a frequent port of call for supplies. In the seas around Erub, these crews encountered people long accustomed to trading with visitors.

The sea continues to inspire artists on Erub today.

Le-op (turtle-shell mask)

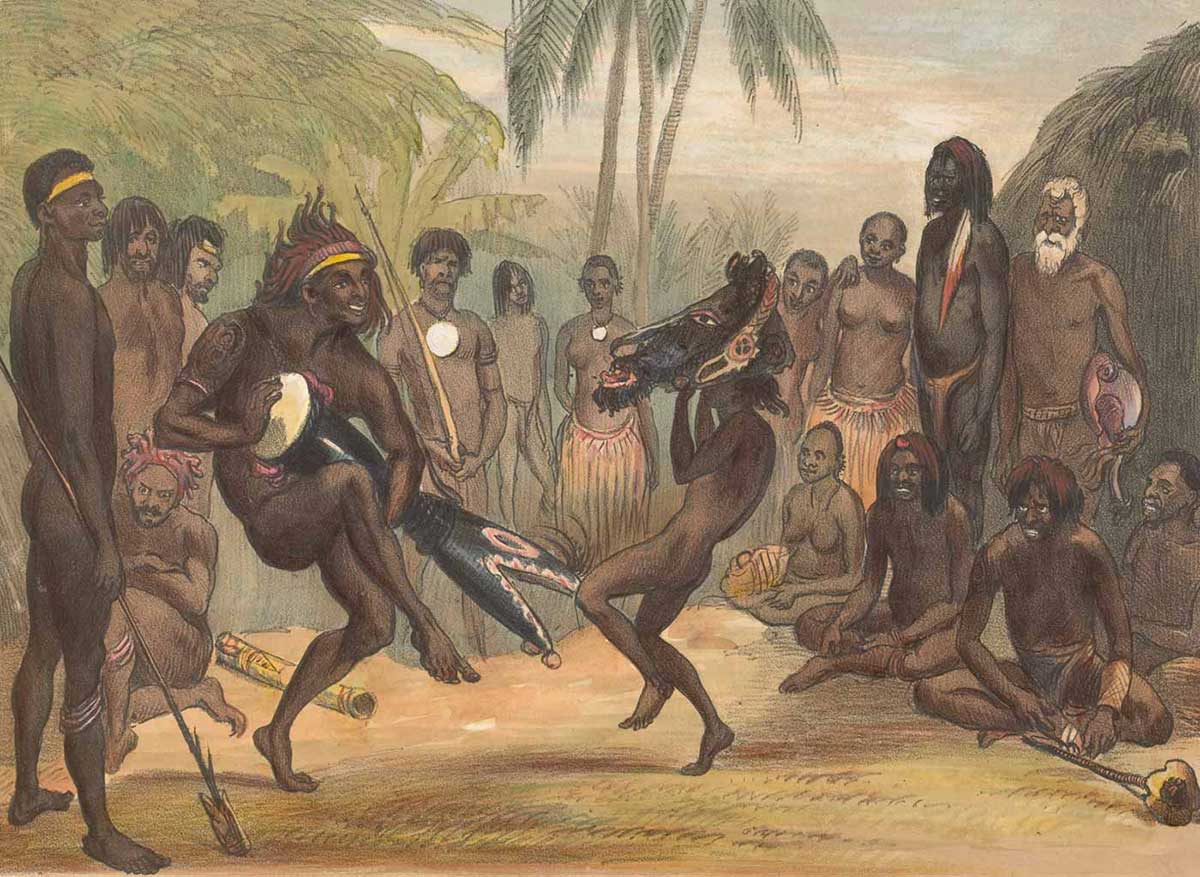

This mask is one of the earliest examples of Torres Strait Islander material known to exist. It was among the ‘curiosities’ collected by the crew of HMS Fly. The visit to the island was part of a British naval project to chart sea routes through the Torres Strait. Scientists and artists, including Joseph Beete Jukes, the Fly’s naturalist, were among the ship’s company.

Joseph Beete Jukes, Narrative of the Surveying Voyage of HMS Fly, 1847:

I purchased for a knife a curious tortoise shell mask, or face, made to fit over the head, which was used they told me, in their dances. It was very fairly put together, with hair, beard and whiskers fastened on, projecting ears, and pieces of mother-of-pearl, with a black patch in the centre for the eyes. This and all the other native implements and curiosities I collected, are now in the British Museum.

A native dance at Darnley

Joshua Thaiday, Erub man, 2014:

I want [people] to have an understanding of all the cultural objects and what it means to us … I want them to make a connection, but also to respect the people that own these artefacts … and you’ll have a better understanding of our culture and our people.

'Loyalty' Dinghy, ghost-net sculpture

The sea remains a source of inspiration for artists throughout the Torres Strait. This dinghy is made from ghost nets — discarded or lost fishing nets and lines — by artists based on Erub.

Florence Mabel Gutchen, Erub elder, 2014:

We are concerned about the ghost net. The ghost net is a threat to our marine life. And the sea, it’s our livelihood ... We talk about the safety for water. Like, please don’t throw things like that to destroy our water. Because the marine life stays. It's for us and for the generations to come ... Because when you look after the sea, it will look after you.

Joshua Thaiday, Erub man:

If I don’t have my culture and the stories and the cultural objects and everything behind it, I am going to be nobody. And if I’m going to be nobody, my sons and my generation after me will be nobody too.

Video stories

Learn about making a ghost-net dinghy

Watch this video about the creation of the ‘Loyalty’ Dinghy sculpture.

Activity: Have a class discussion on what ghost-nets are and what impact they have on the environment? What messages are the people of Erub trying to promote through their ghost-net sculptures? Visit the Ghost Nets Australia website for more.

What do you know about Erub?

More activities

Look at the way recycled materials were used to create the ghost-net sculpture (above). As a group project, use recycled material or materials collected from the shore of a local waterway to create your own sculpture.

Read this quote by naturalist Joseph Beete Jukes in Narrative of the Surveying Voyage of HMS Fly, 1847:

I purchased for a knife a curious tortoise shell mask … This and all the other native implements and curiosities I collected, are now in the British Museum.

Imagine the conversation between Joseph Beete Jukes and a curator at the British Museum on his return to London. Work in pairs to come up with six questions you would have asked Jukes, if you were the curator at the British Museum.

Once you have your questions, pair up with another group and role play — one person can be the curator and ask the questions and another person can play the part of Jukes. After your role play you might like to add some questions to your list.

Explore more on Community stories