Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri country

The Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri peoples have lived in the country that is now the Canberra region for more than 20,000 years.

Explore the Aboriginal heritage and spirituality of the region today.

Setting the scene

Canberra is the host city for the Encounters exhibition. It is also country that has been home to Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri peoples for more than 20,000 years.

Some of their stone tools from Canberra’s Mount Ainslie are now in the collection of the British Museum. One of these, a stone scraper, travelled from Mount Ainslie to London and back for the exhibition — a long journey, through time and space.

Ngunnawal, Ngunawal and Ngambri people continue to live and travel through the Canberra region, preserving their culture by maintaining connections to land and through artistic expression.

Aunty Agnes Shea, Ngunnawal elder, 2013:

As an elder, I welcome people to my country and ask they act and speak with good intentions and I say ‘Ngunna yarabi-yengu’ (you are welcome to leave your footprint on our land).

Aunty Agnes Shea has been identified with the permission of her family.

Wally Bell, Ngunawal elder, 2015:

Our culture is a living culture that’s still developing and growing within itself. We’re learning every day still. As time progresses things are changing. We’re always learning to be adaptable to those changes ... Aboriginal culture is not stagnant like most people think it is.

Aunty Matilda House, Ngambri elder, 2015:

We have always moved all over country. I remember as a little girl just walking over country with my father and him telling me stories for everything.

Stone scraper

William Kinsela, an active collector of Aboriginal artefacts, acquired this stone scraper during a visit to Canberra in the 1930s, searching close to creeks and rivers and in the sheltered parts of hills.

He sent the scraper and some other objects to the British Museum in 1934, with a request that they be exchanged for ‘several small type specimens of English or Continental stone implements of paleolithic man’.

The custodians of the Canberra region reflect on the meaning of country today.

Adrian Brown, Ngunnawal man, 2014:

Stone tools are all over the Canberra regions. They are pieces of country. We leave them where they lie so they will continue to be part of Ngunnawal country.

Tyronne Bell, Ngunawal man, 2015:

Through walking tours we educate people on how to see ‘country’ in a Ngunawal way, and share stories that will build a greater awareness on how to be considerate of country.

Paul House, Ngambri man, 2015:

I don’t know why it surprises people to find Ngambri artefacts in the city and suburbs — the old campsites were the best spots to live. They still are.

My Country, Ngunnawal Country painting

Adrian Brown also made clapsticks painted with the yellow, white, orange and the black charcoal of his country.

Adrian Brown, Ngunnawal man, 2015:

These are the colours of my country. Every stroke in the painting has meaning and connects to that part of my country. The clapsticks are significant because that sound resonates out, calling people, connecting my spirit to country and to ancestors.

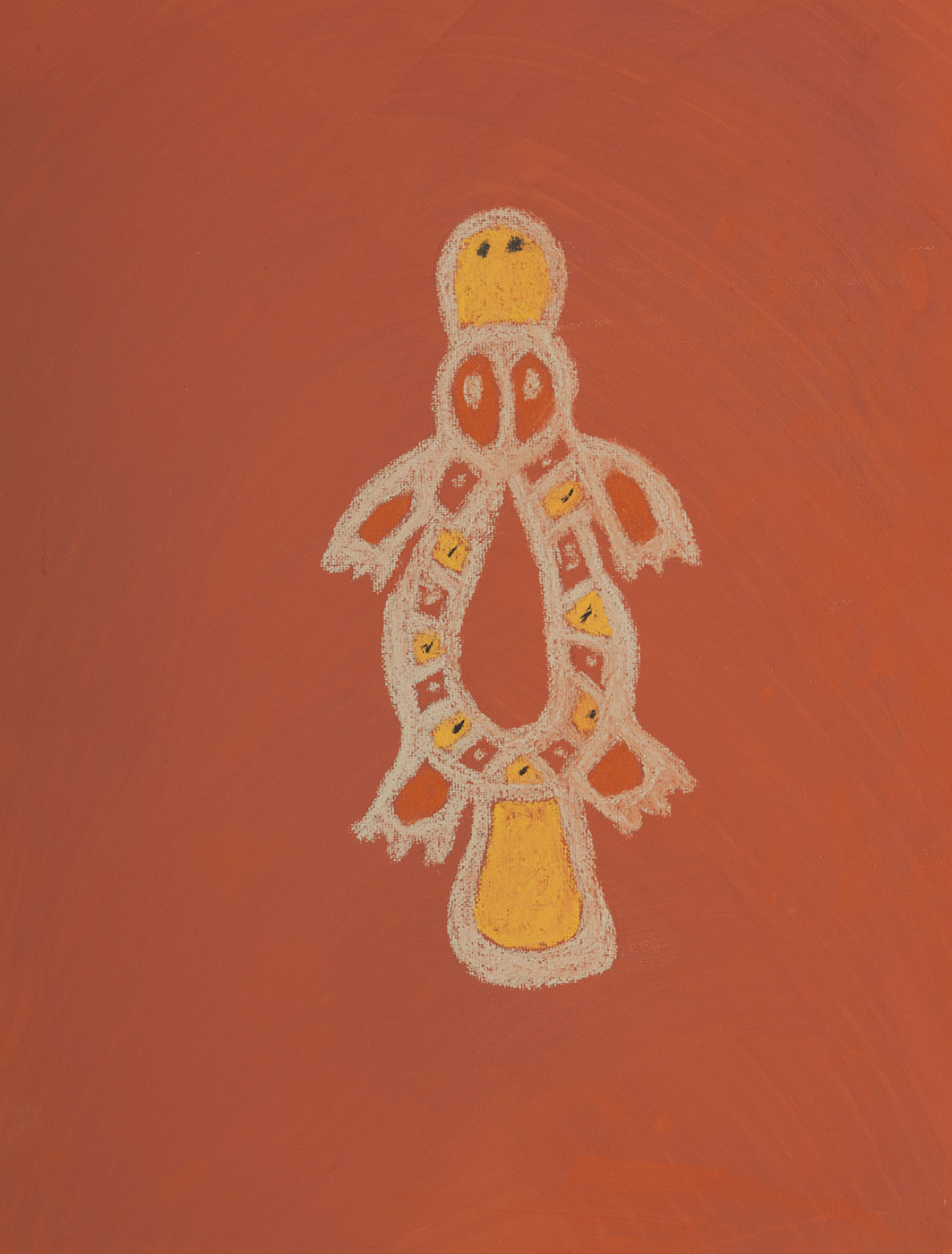

Mulanggang (platypus) painting

Pastoral stations and townships were established in the Canberra region in the 1820s.

Since the 1990s Ngunawal people have been actively involved in consultations and surveys concerning issues of Aboriginal cultural heritage, conservation, parks and wildlife.

Tyronne Bell, Ngunawal man, 2015:

Fresh water is significant to everyone who lives in the ACT [Australian Capital Territory]. We shared waterways with plants and animals, whose wellbeing is just as significant as ours. We are responsible for looking after the land we live on.

Wally Bell, Ngunawal elder, 2015:

Walan [water] is needed by all of us — plants, animals and people. Caring for our waterways is everyday work. Keeping pollution out of our waterways is a constant worry and activity for all of us.

Kicked out of Parliament painting

For thousands of years, Ngambri people have gathered in the high country near Canberra each summer to celebrate the arrival of the bogong moths on their migration south. Attracted by the cool of the mountain climate, moths in their millions seek shelter in rocky crevices and overhangs.

Providing an important seasonal food for the Ngambri and other peoples, they were collected in nets and roasted on fires.

Jim ‘Boza’ Williams, Ngambri elder, 2015:

We have always been known as the Moth people. Tribes from all over came here to celebrate together, and eat bogong moths especially. But not anymore. The bogong numbers are too low — too much city not enough bush, too many lights.

Video stories

Learn about the Welcome to Country

Watch this video featuring representatives of the traditional custodians of the Canberra region: Adrian Brown, Ngunnawal; Tina Brown, Ngunnawal; Wally Bell, Ngunawal; and Matilda House, Ngambri.

Activity: Why do you think it is important for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to welcome people to their country? Can you think of other customs or protocols that apply when moving from one region or country to another?

What do you know about Canberra?

More activities

Ngunnawal man Adrian Brown says his My Country painting (above) connects him to his country:

These are the colours of my country. Every stroke in the painting has meaning and connects to that part of my country.

Do you feel connected to the place where you live or were born? What colours and symbols would you use to represent your country?

Ngunawal elder Wally Bell says his platypus painting, above, represents the significance of water to him and his country:

Walan [water] is needed by all of us — plants, animals and people. Caring for our waterways is everyday work.

What animal could you use to represent something of significance to you or the region where you live?

Ngambri elder Jim ‘Boza’ Williams’ talks about the traditional significance of bogong moths to his people:

The bogong numbers are too low — too much city not enough bush, too many lights.

Think about how changes in the environment brought about by European settlement disrupted the lives of Indigenous peoples in your area.

Explore more on Community stories