Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi country

Aboriginal communities operated complex trading systems. Wirrarri [Birdsville] in Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi country, for example, was an important centre for trading pituri, a stimulant obtained from a local plant.

Explore how the Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi peoples reflect on these traditions today.

Setting the scene

Don Rowlands, Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi man, 2014:

When the whitefellas came they followed our trade routes. This is where the first roads were built, on these trade routes. And every time they built a homestead or a stockyard it’d be on an Aboriginal campsite.

For thousands of years, the Channel Country of south-west Queensland has been part of a complex Aboriginal trading system. Hundreds of people gathered at places like Wirrarri (Birdsville) to trade for weapons, grinding stones, ochre and pituri.

Pituri was a stimulant obtained from a plant (Duboisia hopwoodii) that grows in the region. It was collected, cured, packaged and traded. Traditionally, pituri was used on long journeys as an appetite suppressant and to sharpen the senses during important meetings.

Jim Crombie, Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi man, 2014:

It takes two or three days to dry. They put it in a bag then traded it. They put just a little bit under their tongue. It’s strong stuff, it’s like opium.

The demand for pituri went beyond Aboriginal people. By the late 19th century, colonial scientists, collectors and museums were also keen to obtain samples of the plant.

Bag with pituri

Betty Bunyan, Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi woman, 2013:

This is so precious that it is made from hair. Look how well it’s crocheted, and there will be a lace at the back for opening and closing. I want to hold it. I want to connect with it.

In 1893 William Finucane, a police administrator in Brisbane, wrote to police across the Queensland colony seeking Aboriginal objects for the Police Museum he was establishing in the city. Two years earlier he had received eight pituri bags from Birdsville.

Finucane sold about 40 Aboriginal objects, including the pituri bag pictured here, to the British Museum in 1897 for £10.

Don Rowlands, Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi man, 2014:

The police here in Birdsville have had all sorts of interactions, some not so good, some real good.

Robert Butler, Wangkangurru man, 2014:

I think pituri bags should not have been taken from this country … but we Aboriginal people had no rights in those days … The police here in Birdsville were terrible from what my grandmother told me. But we would not have these things at all if they didn’t take them, because we don’t make them anymore.

Alpunea Jean Barr-Crombie, Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi woman, 2014:

If the white people didn't have this, we wouldn't know about this pituri bag. To know that someone found the bag and looked after it all these years — it's amazing that it's still here. In a way it's good that the white person got it. If he didn't we wouldn't have it today. It's good and bad.

Bag woven from human hair

Joyleen Booth, Wangkangurru woman, 2013:

Hair holds memory of people. My grandmother and mum had a collection of hair samples from family members who had passed away. Also, the cutting of hair was a significant part of mourning. We may not do it anymore, but hair is significant for representing people and their spirit.

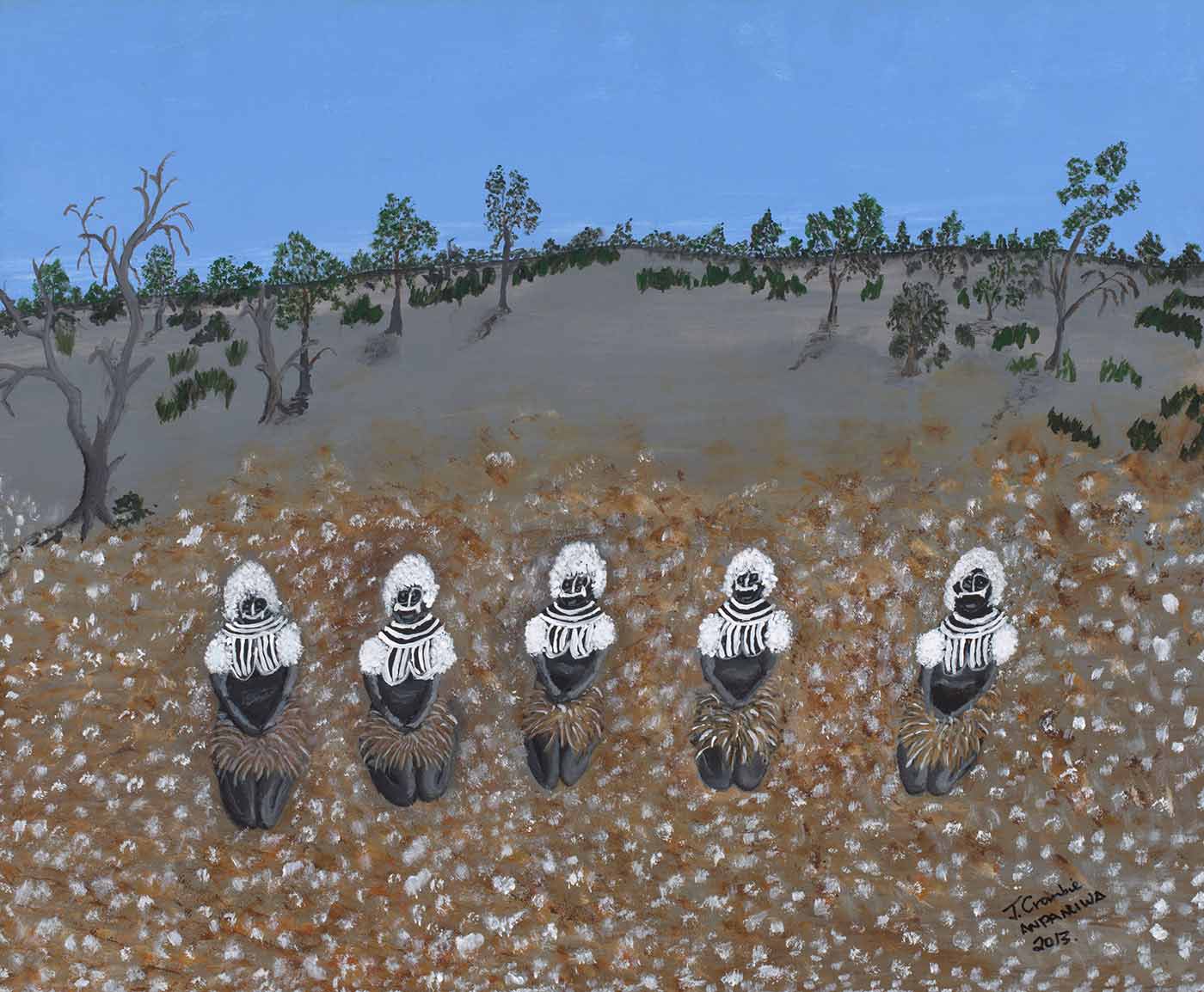

Nanna’s Ready for Dancing

Joyce Crombie, Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi woman, 2013:

This is the story of my family and our lives in our country. Both my grandmothers were medicine women. They came out of the desert. They taught us about country and how to live on it and look after one another. Today, I work as a health officer looking after my people.

What do you know about Birdsville?

More activities

Have a class discussion about the impact of museum collections and removing cultural objects from their place of origin, inspired by this quote from Wangkangurru man Robert Butler:

I think pituri bags should not have been taken from this country … but we Aboriginal people had no rights in those days … The police here in Birdsville were terrible from what my grandmother told me. But we would not have these things at all if they didn’t take them, because we don’t make them anymore.

Take a look at the painting above and consider this quote by artist and Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi woman Joyce Crombie:

This is the story of my family and our lives in our country. Both my grandmothers were medicine women. They came out of the desert. They taught us about country and how to live on it and look after one another. Today, I work as a health officer looking after my people.

What do you think might be some of the similarities and differences between what Joyce does today and what her grandmothers did?

Consider why the location of European roads and buildings mirrored the location of Aboriginal trade routes and campsites, reflecting on this quote by Wangkangurru and Yarluyandi man Don Rowlands:

When the whitefellas came they followed our trade routes. This is where the first roads were built, on these trade routes. And every time they built a homestead or a stockyard it’d be on an Aboriginal campsite.

Explore more on Community stories