On 23 August 1966, about 200 Gurindji stockmen, domestic workers and their families initiated strike action at Wave Hill station in the Northern Territory.

Negotiations with the station owners, the international food company Vestey Brothers, broke down, leading to a nine-year dispute.

This eventually led to the return of a portion of their homelands to the Gurindji people in 1974, and the passing of the first legislation that allowed for First Nations peoples to claim land title if they could prove a traditional relationship to the country.

Vincent Lingiari, 1966:

I bin thinkin' this bin Gurindji country. We bin here longa time before them Vestey mob.

Dispossession

The Gurindji people had lived on their homelands in what is now the Victoria River area of the Northern Territory for tens of thousands of years when in 1883 the colonial government granted almost 3,000 square kilometres of their country to the explorer and pastoralist Nathaniel Buchanan.

The Gurindji would have had no appreciation that someone from outside their community ‘owned’ part of their country.

In 1884, 1,000 cattle were moved onto the land and 10 years later there were 15,000 cattle and 8,000 bullocks. This put incredible pressure on the environment, and the system of land management the Gurindji had developed over many millennia started to break down.

This pattern was repeated across Australia as pastoralists took possession of First Nations lands and stocked them with cattle and sheep.

Traditional ways of life came under intense pressure in this clash between Western and First Nations land usage. First Nations peoples generally wanted to stay on their land; their lives were so connected to the environment there was an existential need for them to remain on Country.

This necessity to stay played into the hands of pastoralists as the cattle and sheep stations required cheap labour, and over the next 70 years First Nations peoples became an intrinsic but exploited part of the cattle industry across Northern Australia.

Exploitation

From 1913 legislation required that in return for their work, First Nations peoples in the Northern Territory should receive food, clothes, tea and tobacco.

However, a report by RM and CH Berndt in 1946 showed that First Nations children under 12 were working illegally, that accommodation and rations were inadequate, that there was sexual abuse of First Nations women, and prostitution for rations and clothing was taking place. No sanitation or rubbish removal facilities were provided, nor was there safe drinking water.

In 1953 all First Nations peoples in the Northern Territory were made wards of the state and in 1959 the Wards Employment Regulations set out a scale of wages, rations and conditions applicable to wards employed in various industries.

However, the ward rates were up to 50 per cent lower than those of Europeans employed in similar occupations and some companies even refused to pay their First Nations labourers anything.

In 1965 the North Australian Workers Union, under pressure from the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights, applied to the Commonwealth Conciliation and Arbitration Commission to delete references in the Northern Territory’s pastoral award that discriminated against First Nations workers.

Pastoralists met this proposal with stiff opposition and argued that any increase in wages should be gradual as this would help First Nations peoples to ‘adjust’. The commission agreed to increase wages but deferred implementation of its ruling by three years, a process that saved pastoralists an estimated $6 million.

Strike action

The Buchanan family had sold what was then called Wave Hill station to the international meat-packing company Vestey Brothers in 1914. On the station, the deferment of the commission’s ruling and the refusal of the Vestey Brothers to pay First Nations workers’ wages led to heated discussions.

Through 1966 no progress was made in negotiations and the Gurindji community led by Vincent Lingiari walked off the station on 23 August.

Consultations went on through the rest of the year amongst the Gurindji, members of the North Australian Workers Union and the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights, but no agreement was reached and the Aboriginal workers did not return to work.

In April 1967 the Gurindji moved their camp 20 kilometres to Daguragu (Wattie Creek). This was a symbolic shift away from the cattle station and closer to the community’s sacred sites.

The change demonstrated a fundamental difference between the view of the Gurindji and that of their white supporters on the purpose of the strike. The Gurindji were focused on reclaiming their land while the unionists believed the dispute was solely about wages and work conditions.

Shortly afterwards the Gurindji drafted a petition to Governor-General Lord Casey asking him to grant a lease of 1,300 square kilometres around Daguragu to be run cooperatively by them as a mining and cattle lease. A key statement in the document was, ‘We feel that morally the land is ours and should be returned to us’.

In June 1967 the Governor-General replied that he was unwilling to grant the lease.

The Gurindji stayed on at Daguragu even though under Australian law they were illegally occupying a portion of the 15,000 square kilometres leased to Vestey Brothers.

Over the following years petitions and requests moved back and forth between the Gurindji, the Northern Territory Administration and the Australian Government in Canberra but nothing was resolved.

Recognition of First Nations land rights

The coming to power of the Labor Party in 1972 changed the political landscape. Prime Minister Gough Whitlam announced in his election policy speech that his government would ‘establish once and for all Aborigines’ rights to land’.

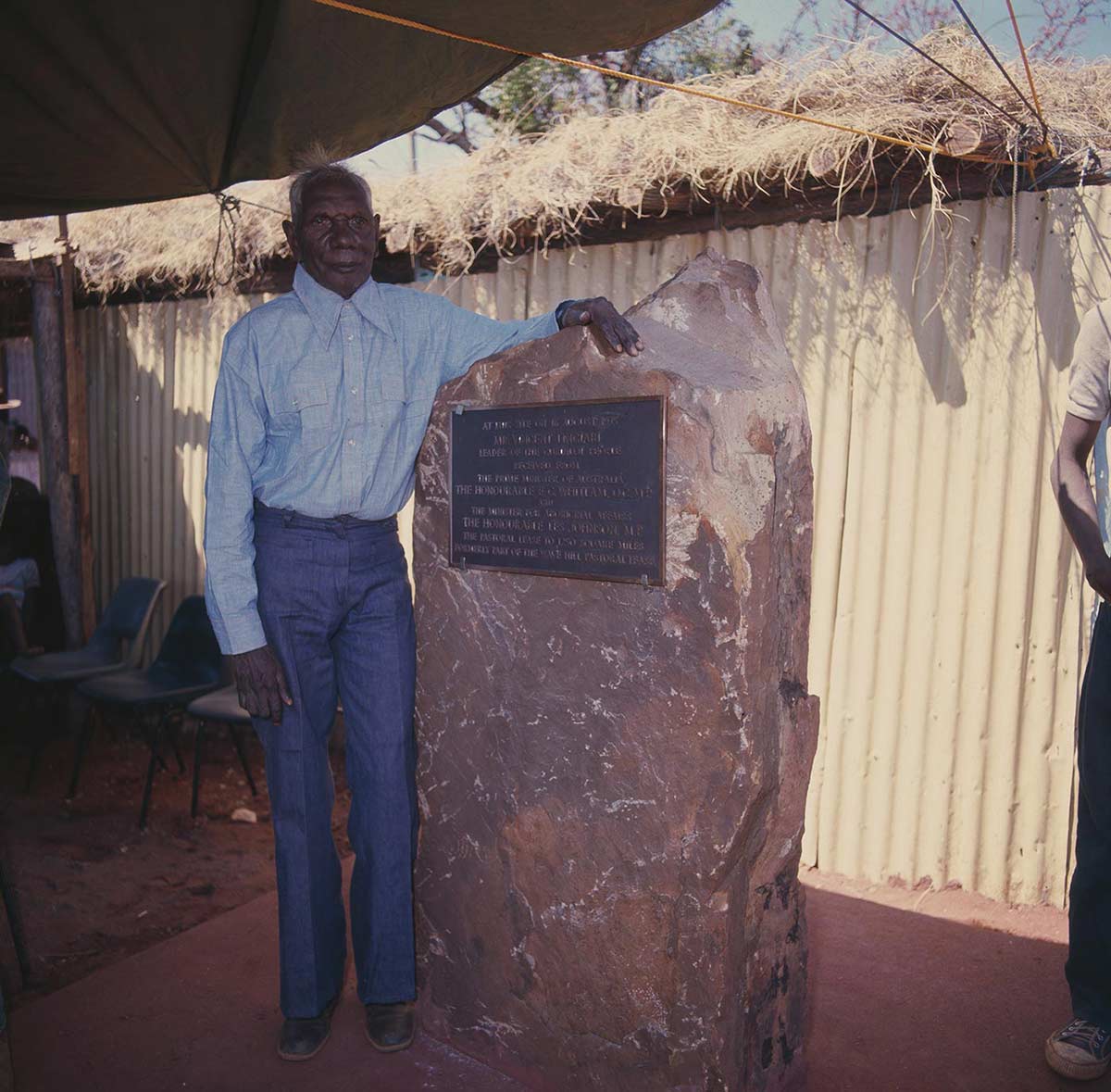

In March 1973 the original Wave Hill lease was surrendered and two new leases were issued: one to the traditional owners through their Murramulla Gurindji Company and another to Vestey Brothers.

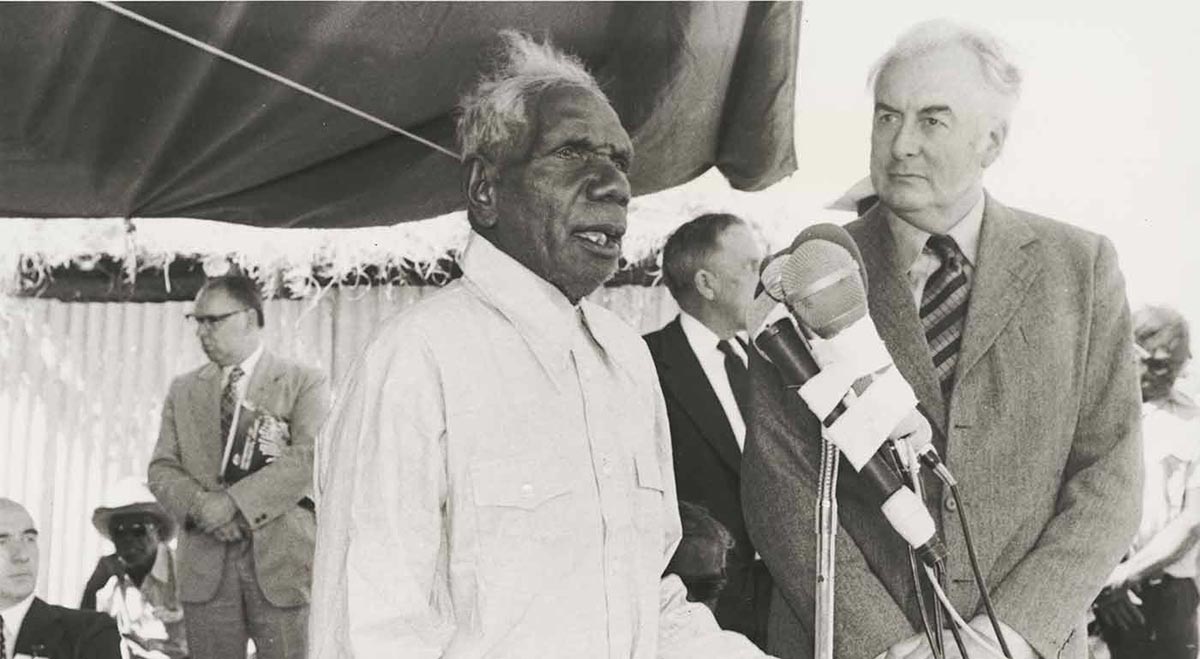

In August 1975 Prime Minister Whitlam came to Daguragu and ceremonially returned a small portion of Gurindji land to the traditional owners by pouring a handful of soil into Vincent Lingiari’s hand with the words, ‘Vincent Lingiari, I solemnly hand to you these deeds as proof, in Australian law, that these lands belong to the Gurindji people’.

The Gurindji strike was instrumental in heightening the understanding of First Nations land ownership in Australia and was a catalyst for the passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, the first legislation allowing for a claim of title if the First Nations claimants could provide evidence for their traditional relationship to the land.

In September 2020 the Gurindji claim for native title to Wave Hill station was granted, 54 years after the walk-off that helped to spark Australia's First Nations land rights movement.

Explore Defining Moments

References

The Wave Hill Walk-Off on the ABC’s ‘80 days that changed our lives’

Vincent Lingiari, Australian Dictionary of Biography

Melanie Guile, Vincent Lingiari and the Wave Hill Walkout, Macmillan Library, South Yarra, Victoria, 2010.

Frank Hardy, The Unlucky Australians, Nelson Publishing, Melbourne, 1968.