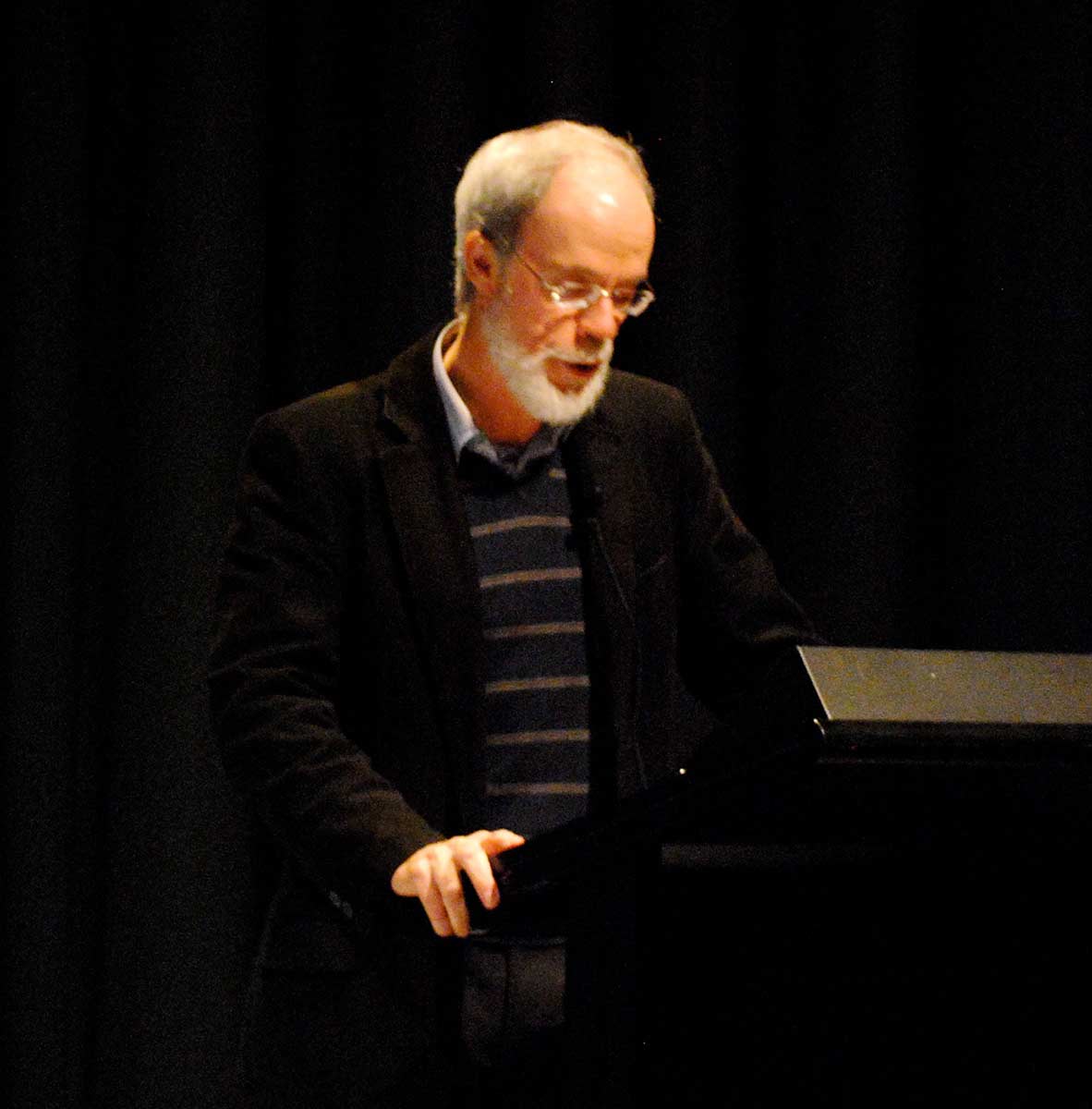

Speaker

Tom Griffiths

Tom Griffiths is a writer and Professor of History in the Research School of Social Sciences at the Australian National University. His research, writing and teaching are in the fields of Australian social, cultural and environmental history, the comparative environmental history of settler societies, the writing of non-fiction, and the history of Antarctica.

Summary

With what we now know of global warming, we can no longer regard carving ice as simply natural. The pace of the event implicates us. The same industrial capitalism that has unleashed carbon has given us a planetary consciousness that reveals a carving glacier as not a random local act of nature, but instead as the frightening frontier of an irreversible, global, historical event. Tom Griffiths contemplates retreating glaciers in Greenland.

Violent Ends: The Arts of Environmental Anxiety 01 Jan 2018

Glacier in Retreat

TOM GRIFFITHS: Exactly a year ago, when I was in Greenland, I sailed perilously close to fragmenting icebergs in an ice choked fjord. I learned later that three to five people die every year in that bay from doing this, mostly Inuit fishermen from a small community of 5000 people and 8000 sled dogs. There’s a famous Inuit fatalism in the face of powerful elemental forces. The great mature writer, Barry Lopez, author of the book Arctic Dreams, wondered what it is like to live in a world where swift and fatal violence is inherent in the land, where suddenly in the middle of winter and without warning, a huge piece of sea ice can surge hundreds of feet inland, like something alive. Or, where an overturning iceberg can generate a ten meter tidal wave and swamp a fisherman.

I was in Alluitsup, under the eaves of the bergs, in Biscoe Bay, at the mouth of the fastest moving glacier in the world. It is now moving 40 metres a day and its pace has doubled in the last decade.

Last November, Greenlanders decisively voted yes in a referendum seeking complete political autonomy from Denmark. This yearning for independence is built on economic optimism about climate change and also on a cultural confidence about long-term Inuit environmental resilience, because as Greenlanders would put it, they survived the Little Ice Age of five centuries ago and the Norse settlers did not.

So Greenland, where increasing numbers of people are dying each year because glaciers are turning into rivers and sea ice has become a dangerously unreliable highway, is nevertheless a part of the world where people can be upbeat about climate change, and where nationalism and global warming are intriguingly and positively linked.

The glacier I visited is a physical and political frontier of climate change. This is where US Senators fly in to get a visceral sense of what greenhouse gases are doing. When you contemplate a carving glacier, you are witness to an ancient, timeless, remorseless natural force — one that makes humans seem trivial, expendable and irrelevant. Ice is abiotic and inhuman.

Yet with what we now know of global warming, one can no longer regard carving ice as simply natural. The pace of the event implicates us. The same industrial capitalism that has unleashed carbon has given us a planetary consciousness that reveals a carving glacier as not a random local act of nature, but instead as the frightening frontier of an irreversible, global, historical event.

So in the early twenty-first century, when you contemplate a retreating glacier, what do you feel? Of course, you are overwhelmed by a timeless wonder and a primal fear. But now there are other feelings too. Moral anguish about humanity’s responsibility, political passion to reduce greenhouse emissions, apocalyptic doom about our prospects, and even perhaps an opportunistic zeal about what your nation might have to gain in the short term.

When discussing the independence vote, some Greenlanders noted that once their ice sheet melts, Denmark — one of the flattest countries in the world — will be underwater anyway. Nationalism can look pretty parochial.

As well as thoughts about the future, the contemplation of ice can provoke a different and deeper sense of history, that boundary between nature and culture — which environmental scholars are always trying to blur — has been violated in the modern era in the most unexpected and shocking way.

Humans have registered on the Earth’s meter as a geological force. Ice may at first seem glassily abiotic, inhuman, and ahistorical. Yet we now know it is a supreme archive. Melting glaciers have been compared to burning libraries. Ice cores from the great polar ice sheets are giving us discriminating annual data of atmospheric change going back hundreds of thousands of years.

The only way to make sense of our current predicament is to look deep into the ice we are losing. It is to go back to the last big Ice Age and beyond, to times of rapid and substantial temperature change. And when we are searching for human parables about surviving really significant climate change, the most compelling examples are not the Inuit people of the northern ice, but the Aboriginal people of our own land.

Thus, while regarding Artic ice, I was struck by the fact that the most inspiring deep time human story for this planetary moment comes from our own backyard, from our own desert, because it takes us, if not into the ice, then certainly into the Ice Age — into the depths of the last glacial maximum of 20,000 years ago and beyond. Into and through periods of temperature change of five degrees and more, such as those we might now also face.

When Europeans look at a retreating glacier, they’re often prompted to tell you that humans and their civilisations are products of the Holocene, the stable interglacial of the last 10,000 years, and that we’re all children of this recent spring of cultural creativity.

By contrast, an Australian history of the world takes us back to humanity’s first deep sea voyages of 60,000 years ago, to the experience of people surviving cold Ice Age droughts in the central Australian deserts, and to the sustaining of human civilisation in the face of massive climate change. This is a story that modern Australians have only just rediscovered, and now perhaps the whole world needs to know it.

Explore more on Violent Ends