Diptych Two

Speakers

Mandy Martin

Mandy Martin is an artist who has held numerous solo exhibitions in Australia, Mexico and the USA and her work has appeared in curated group exhibitions in Australia, France, Germany, Japan, Taiwan, USA, and Italy.

Mandy studied at the South Australian School of Art, 1972–75. She is currently an Adjunct Professor at the Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University.

Libby Robin

Libby Robin is an historian of science and environmental ideas. She is a Senior Research Fellow at the National Museum of Australia's Centre for Historical Research and a Senior Fellow at the Fenner School of Environment and Society at the Australian National University.

She has published widely in history, Australian studies, museum studies, environmental science and the ecological humanities.

Summary

Mandy Martin and Libby Robin converse on the local context of arts for environmental anxiety specifically focusing on the Desert Channels project: a book, art exhibition and educational package that looks at the impulse to conserve.

Violent Ends: The Arts of Environmental Anxiety 01 Jan 2018

Desert Channels

LIBBY ROBIN: In this second panel of the Diptych, Mandy and I want to turn to the local, to the local end of the arts for environmental anxiety.

The Desert Channels Project, which we're talking about today, is about the impulse to conserve. It's in three parts: a book, an art exhibition, and an educational package. We're working with a range of contributors: some scientists, some artists, some historians, and a number of people from local communities.

Let's begin with the Desert Channels. Where are they?

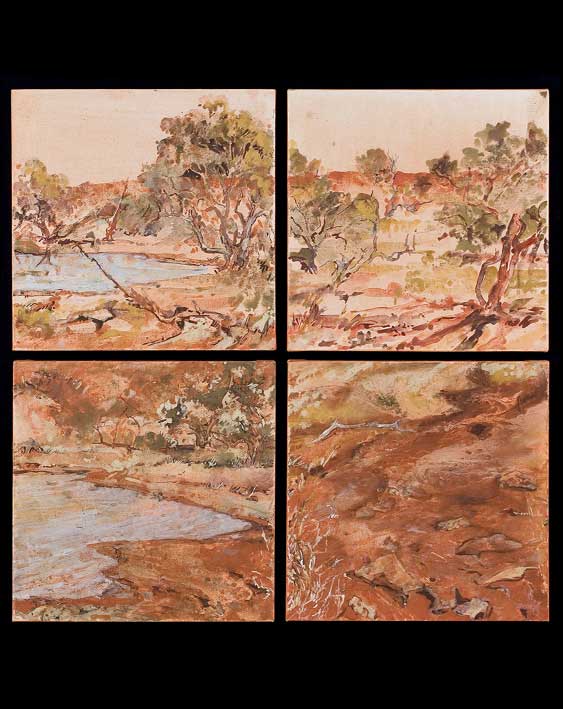

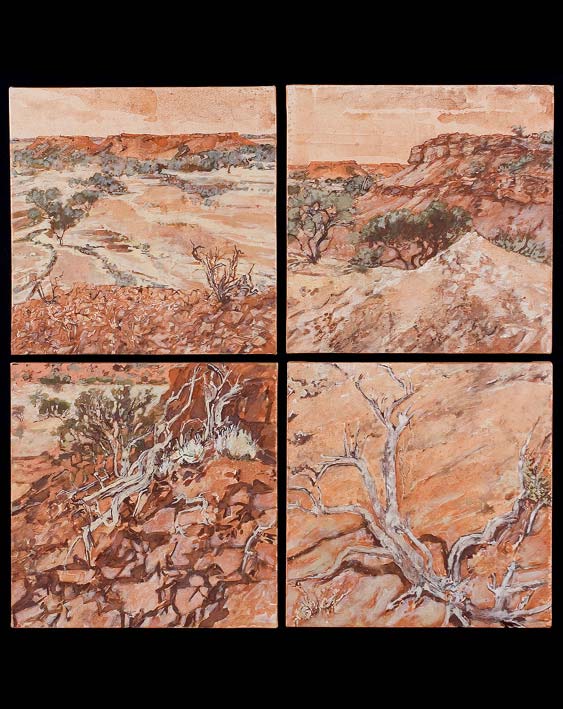

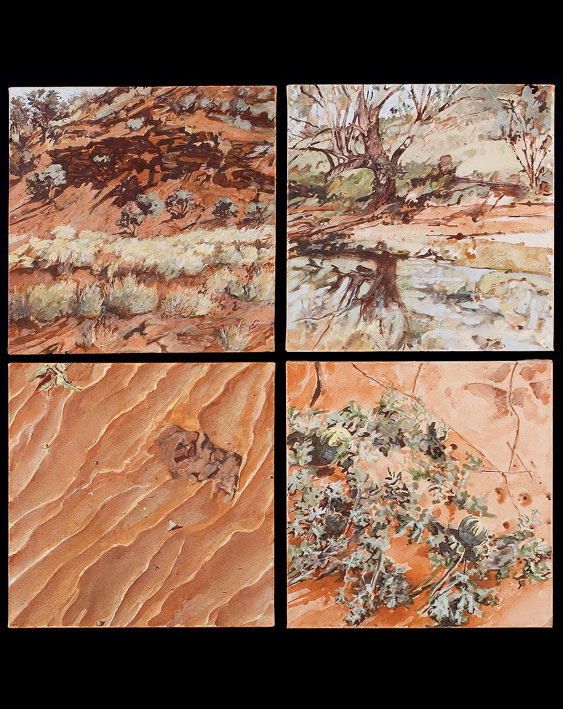

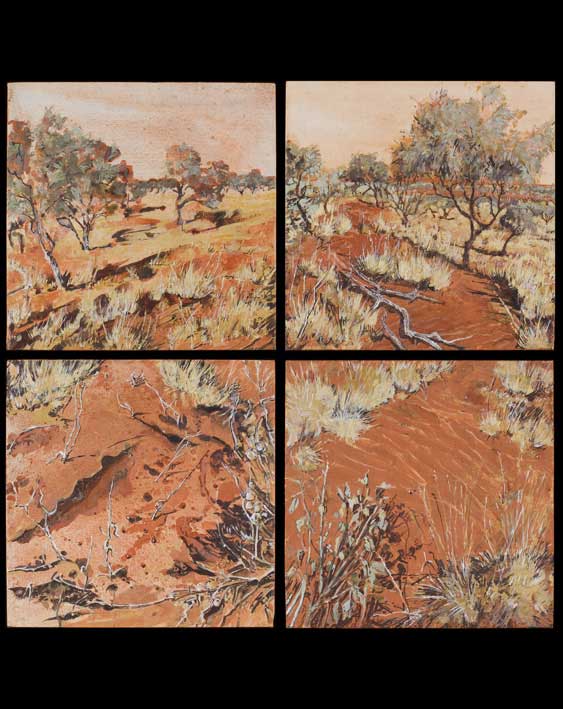

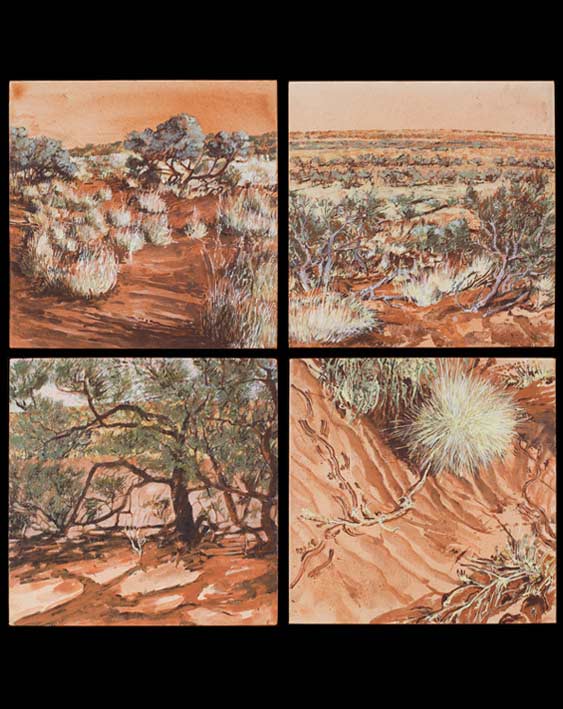

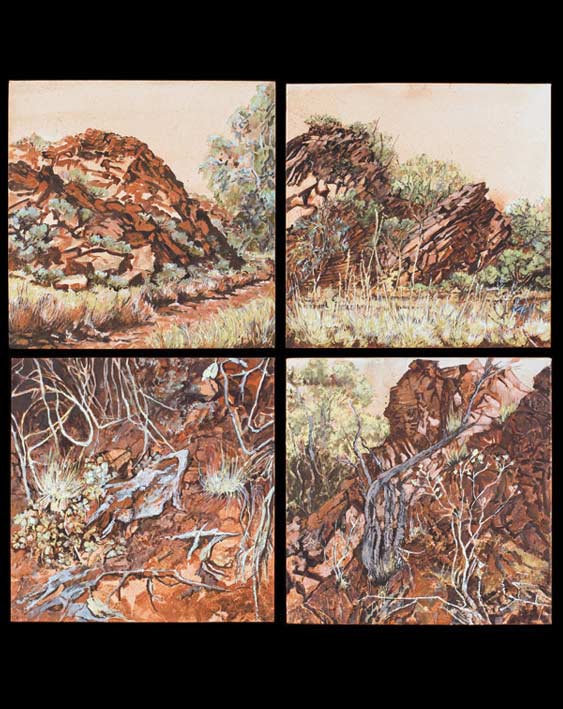

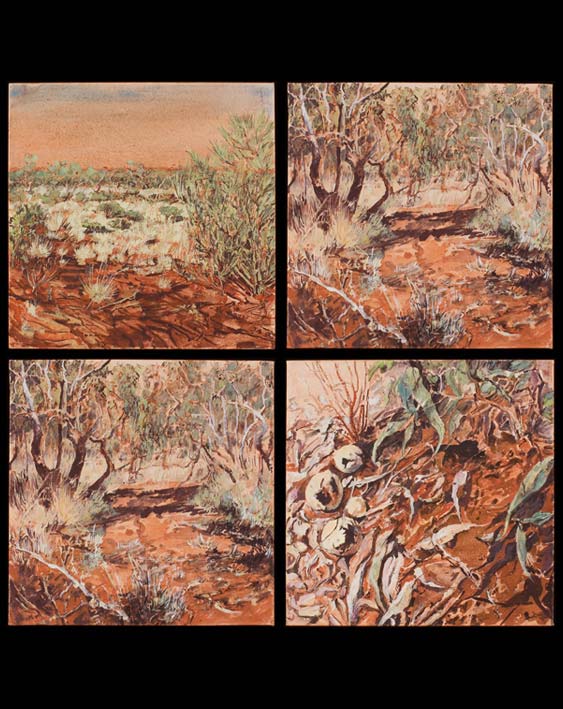

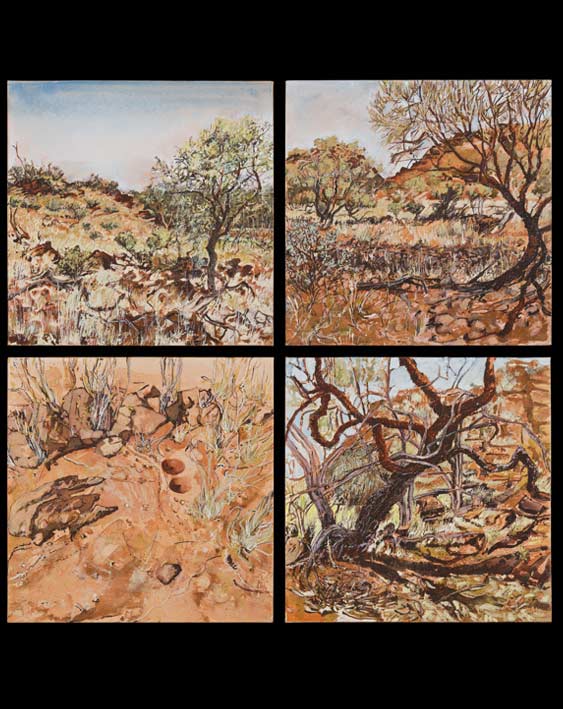

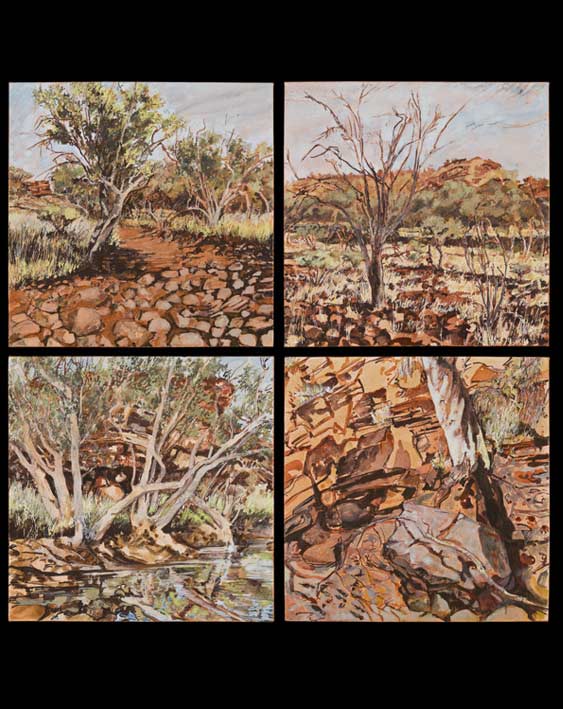

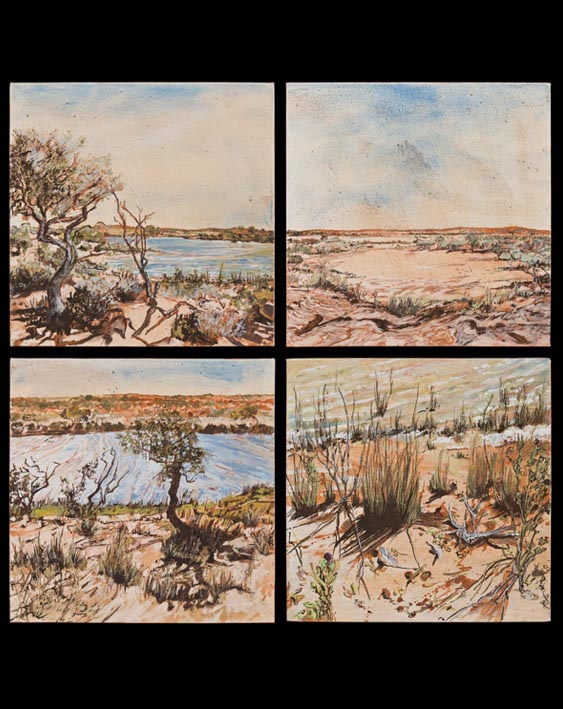

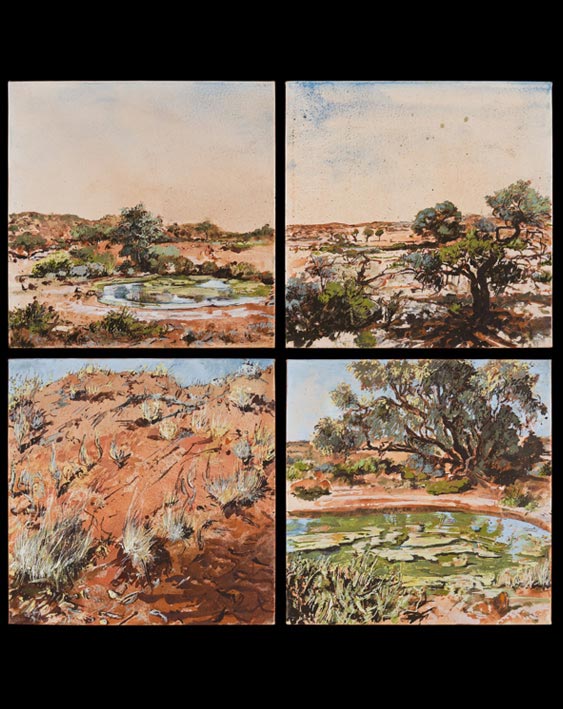

MANDY MARTIN: They're in the south west Queensland, where all the rivers of the Australian arid zone rise. In this region, the rich but erratic river channels and Mitchell grasslands have supported sheep and cattle grazing for over a century. On the western edge of this country, we find the bare burnt oxide gibber plains, and the Simpson Desert's red sand hills. These are the colours that dominate my paintings.

I've been visiting this area for many years, for a decade I suppose. Particularly since 2003, when Bush Heritage Australia bought its first property on the edge of the Simpson Desert. These desert channel landscapes were all painted on location in the three years between 2002–2009, at Ethical Cone Cravens Peak, which were formal pastoral properties, which now are owned by Bush Heritage Australia and run as conservation reserves.

LIBBY ROBIN: Can you tell us a bit more about this attachment to this country, and also bush heritage?

MANDY MARTIN: I've painted this country for every year over a decade, as I said. Initially my painting trips were part of a series of collaborative, interdisciplinary environmental projects. I went out there with people like Tom Griffiths, and scientists, and ecologists, and we did a number of environmental projects. Some of you might be familiar with Watersheds: the Paroo to the Warrego, and Inflows: the Channel Country. It was on the Inflows trip (and Tom was there in 2001) that we first visited the Sydney University zoologists at the Ratcatchers Camp, as it's called, on Ethabuka station. As a direct result of that visit, my husband, Guy Fitzhardinge, who's a conservation-minded grazier, began a process that led to the eventual purchase of Ethabuka.

I've run art workshops out there at Ethabuka, for Bush Heritage supporters, and one of my friends, the architect David Lees, has flown up from Melbourne today for this forum, and he was one of the people along to those workshops. I also chose the area for my master class, and ABC series Painting Australia in 2007.

LIBBY ROBIN: What draws you back?

MANDY MARTIN: I love the arid zone. I think a lot of us do. I want to paint functioning landscapes where they still exist, and in the face of environmental threats from global change, conservation initiatives in this region are important. I like to involve my art in conservation politics. Guy is active in a number of conservation groups, including Desert Channels Queensland, which is an NGO, and an important natural resource management group. He's also chair of the Cooperative Research Centre for Beef Genetics, which is seeking ways to include conservation outcomes in production initiatives.

LIBBY ROBIN: I became interested in this region because I've been researching the history of these new private initiatives, where conservation is working outside National Parks. The Sydney based zoologist that Mandy mentioned, Chris Dickman, and his students have been studying the ecology of marsupials, reptiles, and birds in this area for 20 years. This region contains some of Australia's most important arid zone habitat. Biological studies in this area have been important to understanding ecology across the continent.

Chris is the other editor on this project, with Mandy and me, and he's guiding us in the science. I'm working on the text, coordinating the authors, who come from a variety of backgrounds, while Mandy's developing the visuals. These are not just her own paintings which we're seeing here, but also other contributors' artistic works and photographs.

Mandy, can you tell us a bit about how, as an artist, you came to work with scientists, historians, and others?

MANDY MARTIN: My father was a scientist; my mother was an artist, so it was easy. My daughter's a dancer. Over 30 years, I've made paintings exploring the impact of European settlement in Australia. I've often couched the works in the language of the romantic sublime, as we discussed earlier today. This visual language shaped and coloured settler views of this continent.

I like to use the model of the nineteenth-century explorer artist, working as part of a scientific exploration team, and then adapt it to suit modern environmental projects. The artist explorer mode informs both subject and the style of my paintings, and the way in which I execute them.

LIBBY ROBIN: But how do you actually paint as an artist explorer, in a landscape, with other people?

MANDY MARTIN: Perhaps I can read you a bit from my diary of the 18th of April this year, which is the last trip when we were out in the Simpson Desert, where I think about some of the tensions and benefits of working in a landscape with a team:

I'm painting an east-west transect of 'S' bend on Mulligan River, at Craven's Peak today. I started my first canvas at eight a.m. Somewhat reluctant to leave camp because all our team are there, talking with Chris Dickman and Glenda Wardle's Ratcatcher crew from the Zoology Department at the University of Sydney. Last night we had quite a celebration. It was strange to have about 30 people all camped in a place so remote. A crowd that size could only ever have been there like that in pre-European times.

My first canvas is on the rocky high slope with dead Mulga, and I've got a view of a dry river bed with zebra finches, and crested pigeons are being harried by hawks. I started this morning as soon as the sun became warm enough to dry the water-based pigments on the canvas, and half an hour later I moved on to start the under-painting on the next canvas, down below on the rocky creek bed. Then about 9.30 a.m., I moved again onto a gorge on the west, hoping that the cool shade might grow there as the heat built up during the day to the high 30s.

Over the next hour, I start to work on the final canvas, and I repeatedly visit the four canvases in a sequence during the day, until I'm either exhausted, or I have enough information to leave them and finish them when I get back to my studio.

The last kangaroo footprints from when water was in the creek are clearly visible in the dried mud. I watch zebra finches flitting in and out of the Mineritchie that I'm painting. Its elaborately twisted trunk's decorated with dense grey bark curls over a smooth ox-blood red trunk, embracing a tormented Mulga stripped of its foliage. The living and the dead trees dance a grotesque duet, something the artist Salvator Rosahimself would not have dared invent, but I'm right.

A Cray hangs about trying to spirit me; am I in someone's place? Should I have sought permission first? I wonder if it will pinch my brushes when I turn my back to tend my next canvas.

Will the light move dramatically before I return so that I'll have to remember how it is now and fix it from memory? Perhaps the wind on the other side of the valley will whip the whole canvas off my easel ironing board in a gust of disapproval.

LIBBY ROBIN: This is a region outsiders only visit with permission of landholders. Few people visit this camp site on the Georgina River, almost on the Northern Territory border, where Mandy was painting and I was writing the same day, working on my part of the project. But how does an artist respond? What's truly local about the colour and the dynamics of the Simpson? What should we be valuing aesthetically, Mandy?

MANDY MARTIN: I want to develop marks and a palate, a new vocabulary, I suppose, for Australia's arid zone. We need to understand it in its own terms. My landscape studies are mimetic but not without drama. Each place is carefully fixed in time. As I said, leaves are not often green round and fleshy, they're more commonly grey spikes. A landscape seemingly with nothing in it actually is full of incident. Painting and selecting what to keep in or leave out is complex. There're so many accidents of nature. The sun shifts rapidly and changes everything suddenly. And shadowing is rarely dappled as much more often sharp and unforgiving. Fixing the light and shadow is a major decision that reveals the drama in the landscape.

To capture the real colour of the sand on a canvas, for example, I add a little bit of metallic copper oxide, which, as it contains mica, always has a flat surface and reflects the light just as sand particles do in the sun light. I want to show the place as it is and also to show it has aesthetic value.

LIBBY ROBIN: The project is all about different values. Bush Heritage owns and manages properties for biodiversity conservation. Most of its neighbours are producers of cattle rather than biodiversity. Many of these people are also passionately concerned about conservation. Biodiversity is the basis for one sort of conservation. Among pastoral neighbours there is also a passion for cultural heritage, both Aboriginal and pastoral.Water is a major concern across the whole community. Artesian flows have been slowing down and the rivers may be threatened by climate change. We may even see a collapse of this complex local system in our lifetimes. People fear that in this country they love, they may be about to witness a violent end.

Artworks

Presented by Mandy Martin during the discussion on Desert Channels

Explore more on Violent Ends