Diptych One

Speakers

Mandy Martin

Mandy Martin is an artist who has held numerous solo exhibitions in Australia, Mexico and the USA and her work has appeared in curated group exhibitions in Australia, France, Germany, Japan, Taiwan, USA, and Italy. Mandy studied at the South Australian School of Art, 1972–75. She is currently an Adjunct Professor at the Fenner School of Environment and Society, Australian National University.

William Fox

William Fox is a writer, poet and the Director of the Center for Art and Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno. His work is a sustained inquiry into how human cognition transforms land into landscape. His numerous non-fiction books rely upon fieldwork with artists and scientists in extreme environments to provide the narratives through which he conducts his investigations.

Summary

The Anthropocene began in the late eighteenth century when the activities of humans first began to affect the Earth’s climate and ecosystems. In this first diptych Mandy Martin and William Fox discuss how Mandy’s work reflect images of human weakness or folly in the face of climate change and how her paintings connect Australia with the grand European tradition of the romantic sublime — a movement that arose, in part, as a reaction against the initial industrialisation.

Violent Ends: The Arts of Environmental Anxiety 01 Jan 2018

Art for the Anthropocene

WILLIAM FOX: Good morning my name is Bill Fox. I’m the director for The Center for Art and Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, Nevada, United States. And I’ve been fortunate enough for the last three years to be a visiting fellow here in Canberra, both with the Research School of Humanities at ANU, and at the Centre for Historical Research here at the Museum. So, it’s a remarkable pleasure for me to be here as a co-convener at an event hosted by these various institutions this morning. And Carolyn Strange, especially a ‘thank you’ to you.

The books I write are about human cognition and landscape. I was brought here as a writer. And these books have everything to do with art, the environment, climate change, and Mandy Martin. Mandy is one of Australia’s major painters, of course, but she’s also known globally as an important artist. She was born in Adelaide and she’s exhibited in numerous countries. She was a founder of the Environmental Studio at ANU School of Art. And she’s currently an adjunct professor at the Fenner School of Environment and Society. So please help me welcome Mandy Martin.

[applause]

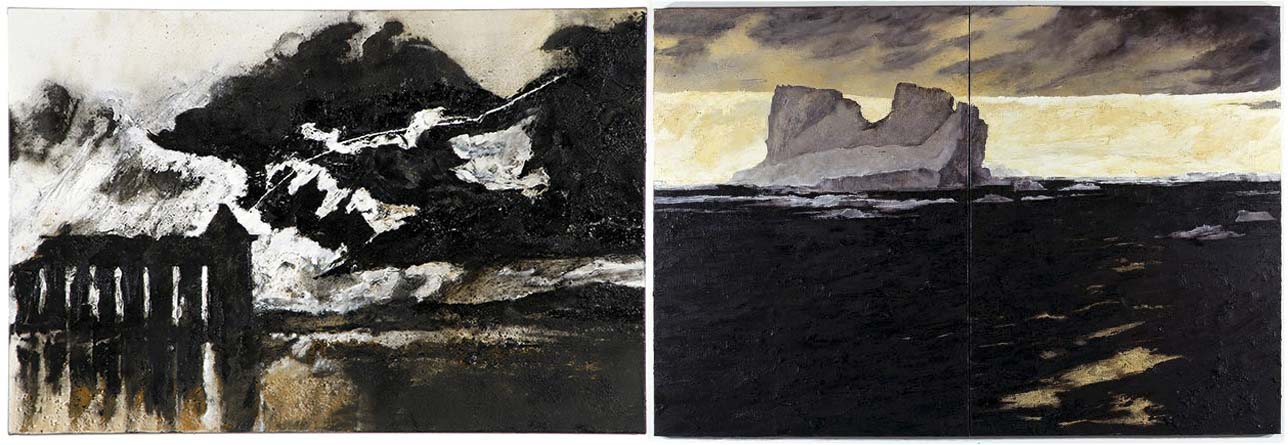

WILLIAM FOX: Mandy, your painting Thunderstorm over Paestum, after Turner, after JMW Turner, this is the image on the Violent Ends flier as well. This connects us here in Australia with the grand European tradition of the romantic sublime. And that’s a movement that arose, in part at least, as a reaction against the initial industrialisation of the world, which is when we began to release massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere. Did you have that in mind at all when you were painting this?

MANDY MARTIN: Turner associated lightning with the monuments of dead religions and I’ve made a painting from his sketch, a small sketch of the demise of the ancient Greek era of civilisation. And I’ve been interested in painting images of human weakness or folly in the face of climate change, which is why I painted this homage to Turner. Turner was not the first artist to observe violent climatic conditions and to see them as metaphorical. And Breughel’s Hunters in the Snow, which everyone in the room would be familiar with, was also a document of the Maunder Minimum: a partial ice age during that period of European history.

WILLIAM FOX: Well, looking at the show here, Mandy, in your retrospective that you have at that Canberra Museum in gallery right now, there’s this large iceberg floating in this black sea - tremendous painting. It’s part of your series that’s called Wanderers in the Desert of the Real. What does that mean? And why is this iceberg one of those wanderers?

MANDY MARTIN: Well, Tom Griffiths, who’s sitting over here and he’ll be talking this afternoon, actually took the original photograph. And I’m indebted to him. I’ve never been to Antarctica. I don’t know if I really want to go. But, I have flown around an iceberg marooned off New Zealand, and even landed on it, but on You Tube, I’ve done it in virtual space.

[laughter]

The Wanderers in the Desert of the Real series, that prefix comes, I’ve used it in 2008 and 2009 series of paintings. It comes from a post-modern philosopher, Slavoz Zizek. And the full sentence, which I first encountered in Martyn Jolly’s article in a monthly in Art Monthly in May 2007, reads ‘Our reliance on prostheses has turned us all into wanderers in the desert of the real.’ So I’ve created a whole array of wanderers, and we’ll see some of those in the next sequence.

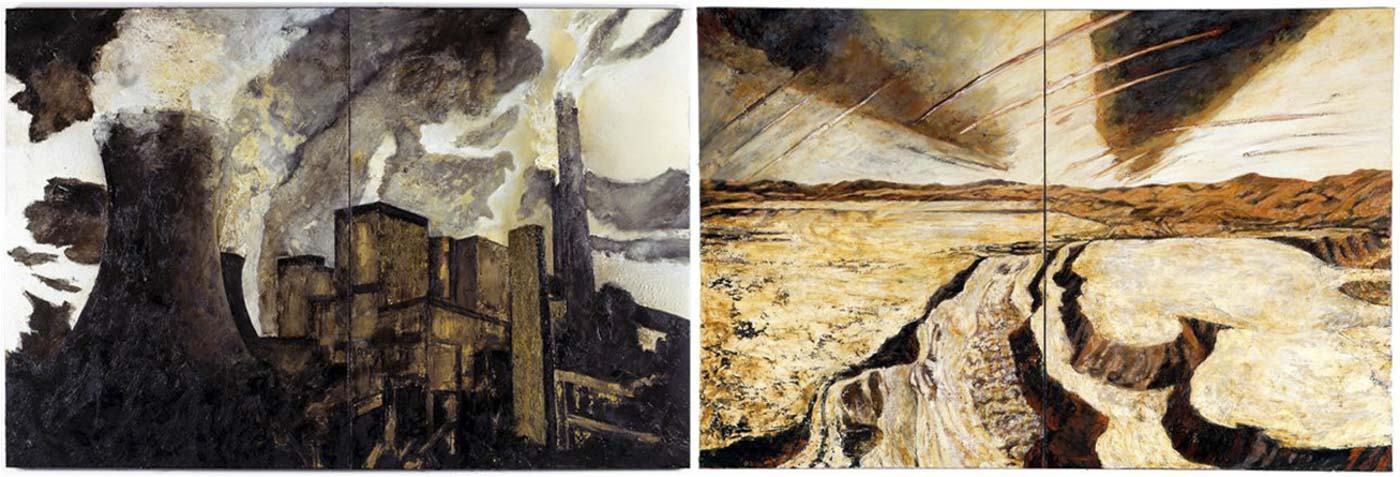

WILLIAM FOX: You know, this next book that I’m working on - the book that I’m here for actually this time and to work in part with Will Steffen - is called The Art for the Anthropocene. And I talk about your work in the global context in that book, of how landscape, art and earth system science developed together. And as part of that history, how your art often proceeds actually from the industrialised landscapes of Australia - so from icebergs to industry.

MANDY MARTIN: I believe we need to look at climate change, not only from the global view point, but the local. And today, we go from the global to the local. But, this is on a site where Wallerawang is less than an hour away from where I live in central west New South Wales. And it places me squarely in what, for those of you who read Guy Pearse’s last quarterly essay on coal titled Quarry Vision: Coal, Climate Change and the End of the Resources Boom, says effectively is the greenhouse ghetto of Australia. So, that’s where I live. He continues, ‘Each advance in our coal-fired development has made emission cuts harder: a new aluminium smelter powered with coal, for example, is the emissions equivalent of adding a million cars to our roads: if we attract four new aluminium smelters, the greenhouse benefit we might gain from putting solar hot-water systems on every house in the country would be erased’.

And for those of you who actually do get Quarterly Essay, Guy’s got a four-page response to letters to that article in the current essay. And it brings us up to date on what’s happened in May. And I think he will have to keep doing it.

WILLIAM FOX: You know in this last book of mine that just came out called, Aereality: On the World from Above, Mandy and I had taken a flight together over the Cadia Gold Mine, another one of Australia’s industrialised landscapes. And this is one of the paintings from that experience.

MANDY MARTIN: Yes. I live in an absolutely idyllic landscape, but this also is on the horizon from where I live. It’s the second biggest open cut in Australia. There’s also, on my doorstep, a constant reminder of the real environmental price we pay for our vanity. Because essentially 97 per cent of the gold dug out of the ground is used for jewellery and bullion, and three per cent for dentistry and so on. All this for the havoc it wreaks on our environment. The sheer consumption of fossil fuel is absolutely staggering, and electricity, 42,000 litres of diesel a day, three per cent of the New South Wales power grid, the machines never stop running — all for 750 ounces of gold a year, worth about US$950 an ounce.

WILLIAM FOX: We have the same thing where I come from, in the State of Nevada, where they take down entire mountain ranges and turn them into things that look like ziggurats. Making gold for gold Rolex watches. It’s amazing. Mandy, your wanderers really wander. They go from these natural phenomena, such as icebergs, to industrialised landscapes. How do the paintings talk to one another, and how do they talk to the larger world?

MANDY MARTIN: The Wanderers’ works are deliberately in dialogue with each other. And this is an installation shot of my exhibition last year, at Roslyn Oxley Gallery in Sydney. You can see some of those paintings that I’m referring to, the Tailings Damsthere on the left. So, that painting... During this period of heightened awareness of global warming, the dialogues are obvious, but I’ll lead you through a couple of them. On the right hand side there, there’s a painting called Tanami Spinifex Fires. I’m really interested in the functioning and resilient landscape, as well. I’m not just all doom and gloom. It’s always in my mind’s eye, and that’s the reason for painting that particular landscape. One that of course faces the threat of climate change, obviously. I do spend a lot of time working on environmental projects in the arid zone. So, that is part of my community of interest. My dialogue, this afternoon, with Libby Robin is about that specific thing.

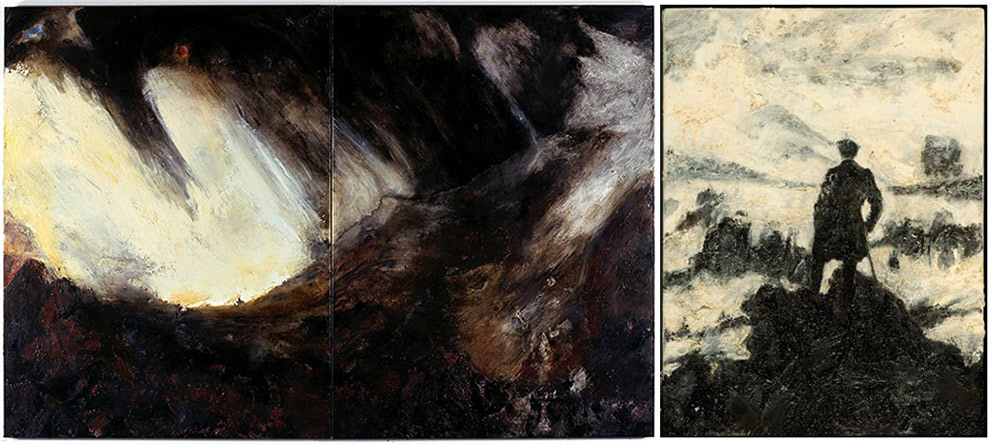

WILLIAM FOX: I flew in from Los Angeles, actually to come here a couple weeks ago. We have these cataclysmic fires in Los Angeles, almost in direct opposition to this enormous urban grid that’s been created there, what is, in essence, a semi-desert. Here, as in Los Angeles, fire and flood are part of natural cycles. We have floods in Los Angeles, too. They’re not just violent ends, but they’re also renewals, of a sort.

MANDY MARTIN: I see the termite mounds as one of the natural world’s great triumphs. They are magnetically in line north-south, and they have complex adaptations for cooling and warming. They are miracles of engineering, and the natural cooling towers next to... I put these next to the man-made cooling towers from the power stations. This is the cool spinifex fire, either lit by lightning, or by passing Aboriginal traditional owners. And it’s back in the spinifex, but it will soon have a bright green shoot. So cool fires are good fires. And this landscape relies on cool burning for its healthy resilience. The other painting in the installation shown at Roslyn Oxley was Deluge after John Martin. I’ve often referred to John Martin, known in his day as Mad Martin. Of course, I’ve often been called that, too. Because he outrageously designed systems for underground sewerage in London, and flood controls for the Thames, which, during that period, was pretty radical. There’s an echo also of the Chiliastes, who earlier predicted the demise of civilisation. And Martin reflected the late nineteenth-century Millenialists’ fear of the industrial era, and destruction of the world, as we know it. He used motifs of towering waves, and the world rent by earthquake. And in his painting of Macbeth, there’s an icy green glacier that fingers its way into the middle of the picture.

WILLIAM FOX: Humankind’s interventions in the landscape, these attempts to control fire and flood and ice, have long been understood by artists to quail in the face of nature’s power. And Turner, of course, as an artist, expressed that as well as anyone. Which is why, I suspect, you quote him as much as you do in your work.

MANDY MARTIN: Yes. I feel Turner in Hannibal Passing the Alps hits with precision on the human folly to believe that we, in our insignificance, can face insurmountable odds. Also our vain glory and faith in believing that we can, literally, move mountains. Still, it seems our gaze was indeed malevolent, and we’ve literally destroyed in this period of the Anthropocene, all that we believe we own. And also, our spiritual centre. Having said that, for me the use of the sublime, of course, is an acknowledgement of that very spiritual centre. As Imants Tillers says in The Monthly, I think in his credo this month, of course in making art, could there not be a spiritual centre.

WILLIAM FOX: Yes. Another famous example of the romantic sublime of course is a painting by Casper David Friedrich, Wanderers in the Mist, or Wanderers above the Sea of Fog, an alternate title for it. It shows a man dressed in a Forester’s long coat contemplating the infinite aspect of nature. For me, at least, this is a relatively rare aspect in your work, where we actually have a figure in your landscape. That’s because I don’t know all the paintings.

MANDY MARTIN: If you look closely at the survey shown over at CMAG, at the moment, you’ll see there are a few figures tucked in there. But yes, no, I agree with you, in one sense. The figure running through the dust and smoke in this painting, for example, is fully vulnerable and this painting brings together the cumulative interests from the past decades for me. There’s a genuine fear for not only ourselves, but the future of the Australian landscape that we inhabit.

WILLIAM FOX: Alexander von Humboldt started setting connections between climate and the environment during his expeditions in South America, at the turn of the eighteenth and into the nineteenth century. And Frederic Church, the artist of course, followed his footsteps, literally, up the avenue of the volcanoes to make these paintings that represented the system of the world. It’s these huge encyclopedic paintings. And Mandy, I find your work falling in that tradition precisely. There you are, out on expeditions, for example, in the desert. Making these paintings that pull together the world. I think you’re doing that in a tradition that is very particularly Australian, in part because we’re here in a continent that is the most vulnerable, potentially, to a violent end. So, I think your work fits within this tremendous, at least 200-year tradition of work like this.

I also just want to say that I think the world has a lot to learn from Australia. And I think part of what we have to learn is not just the potential for the violent end, but also that for the renewal. And I always see those possibilities in your paintings as well.

MANDY MARTIN: Thanks, Bill.

WILLIAM FOX: No, thank you very much.

Artworks

Explore more on Violent Ends