Connecting people and places

People with diverse geographical and cultural backgrounds attend agricultural shows. These popular annual events enable encounters through which people discover how they are different from, and similar to, other people.

Inside pavilions, beside bountiful displays of produce, gardeners exchange knowledge and collectively place value on the physical and intellectual activity of generating food from earth.

The many children who plod or run past shelves and trestle tables laden with pumpkins and jam see, feel and smell fruits strange and familiar. Some imagine the carefully arranged produce in relation to gardens and kitchens they know. All form memories that they will carry for decades.

Many adults who grow and exhibit produce hold such memories. Rich childhood experiences in productive gardens and at agricultural shows often underlie adult motivations to contribute towards these collaborative community efforts to honour skills and knowledge in gardening and other embodied pursuits.

With the emergence of the school kitchen garden movement, schools and their students are increasingly entering garden produce in agricultural shows. Children are becoming active participants, especially through displaying their creative capacities in the novelty fruit and vegetable section.

Through this participation, they are encountering people of different ages and backgrounds, and an array of produce carefully nurtured in other places. Together with adults, children are helping to maintain a lively interest in growing food.

Learning and change

Growing and producing food for agricultural shows (and for the table) provides opportunities for continual learning.

Even experienced exhibitors acknowledge the endless opportunities to learn and change their practices. Although entrants often possess knowledge of what specific plants need to grow, when and under what conditions, environments change not only from season to season but from year to year.

What grew well one year may not grow well the following year under drier (or wetter) weather conditions. An heirloom variety may produce well in one year and not in another, or specific insects maybe an issue in some years, whereas in others it may be fungus or a plague of mice.

Thus the process of growing food is one of continual learning, change and adaption to conditions.

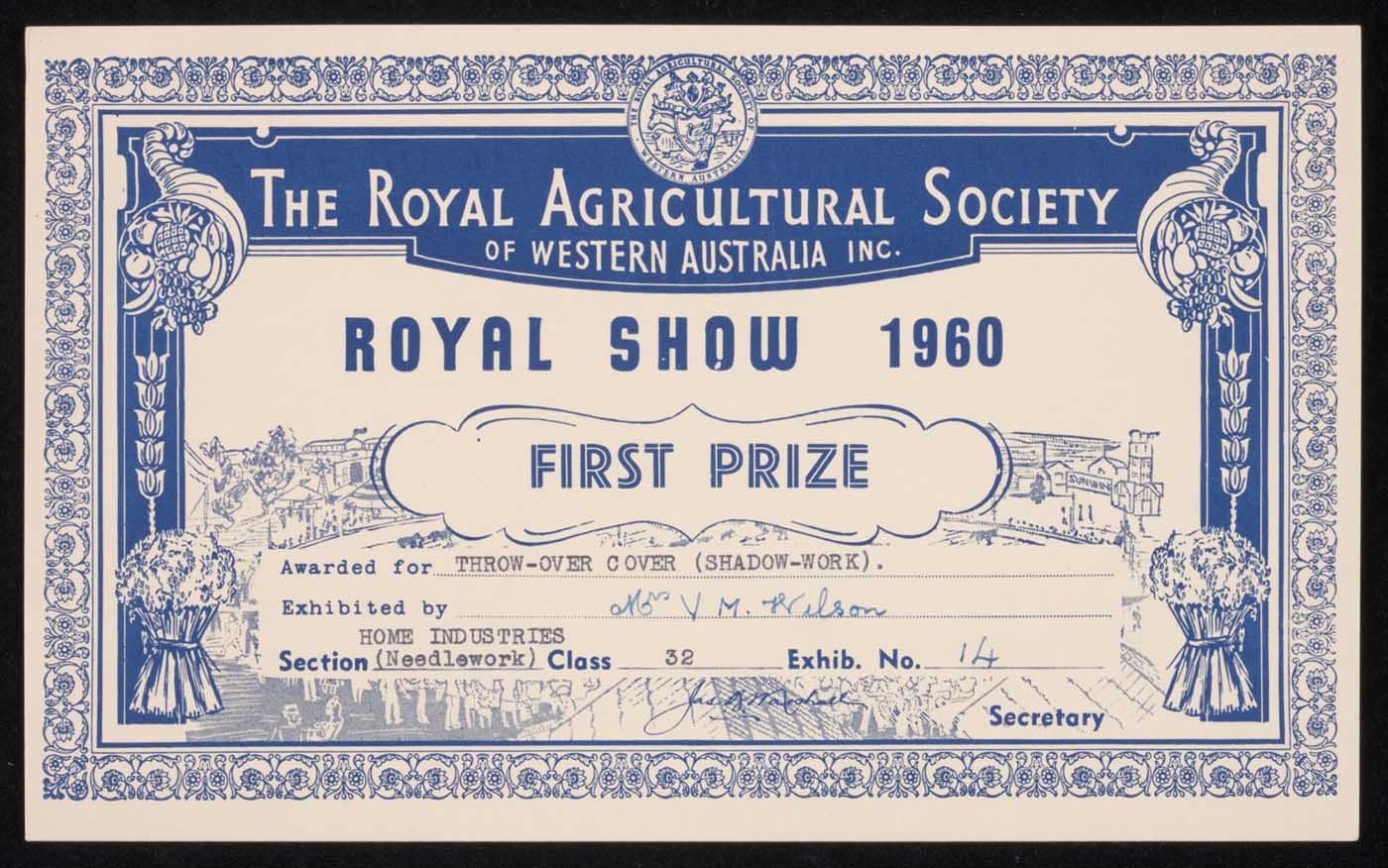

Entrants exhibiting produce in agricultural shows seek out feedback on entries from judges at the show. A desire to improve and enter even better produce is often at the heart of this action. Judges provide extensive feedback to interested members, and this is often incorporated into next year’s entry.

The largest audience can often be found in the cakes and preserves section where numbers of people sit and listen to the judge’s feedback on the jams, preserves and various cakes, scones, tarts and biscuits.

Entering food into agricultural shows also provides entrants with a heightened awareness of food systems. Agricultural shows demand ‘perfect’ entries — it is perfection that is rewarded with ribbons and medals.

Growing produce for the show highlights for entrants how challenging it is to attain this perfection. Fruit and vegetables can be misshapen and marked — either from pests or birds or some other natural element.

In a highly commoditised Western world where supermarkets sell ‘perfect’ produce in a range that often belies seasonality and local production, agricultural show produce entrants appreciate the processes and costs involved in ensuring year-round availability. These include long-range transportation and quality control to ensure specified standards are met.

Urban produce gardeners understand the challenge of producing perfection: for every ‘perfect’ tomato suitable for show entry, there will be kilograms of imperfect specimens. What happens to these imperfect specimens in mainstream agricultural production?

A convergence of urban and rural

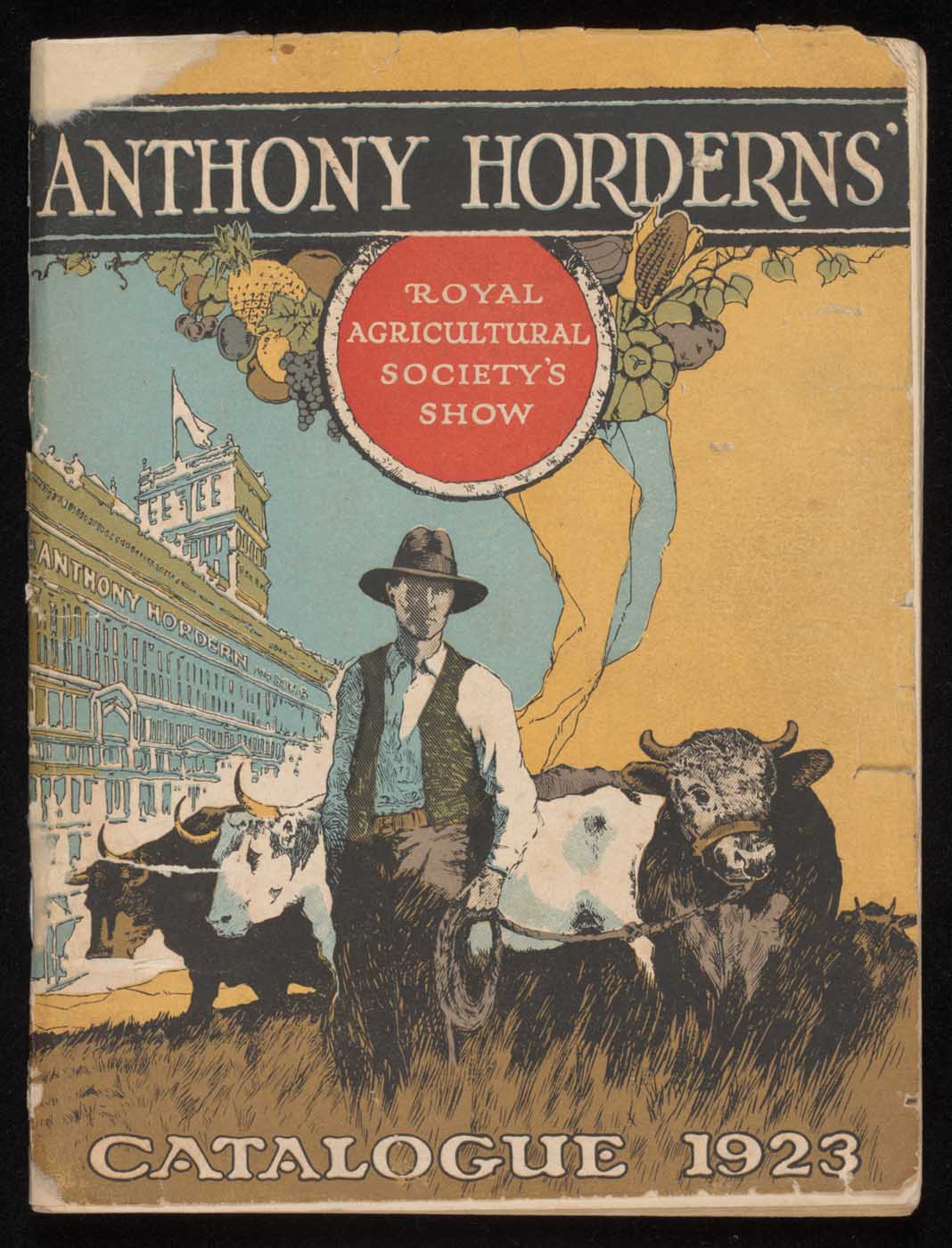

Agricultural shows operate in ways that both challenge and reinforce established understandings of the geographic and cultural domains that we call ‘urban’ and ‘rural’.

In larger urban centres, show societies often promote their annual gatherings as ‘the country coming to town’. They present rural terrain, people, and livestock as ‘other’ to urban existence, a zone of difference against which to define identities of cities and their residents.

Notions of rural/urban differences and divides are frequently imagined and emphasised to serve the interests of particular groups.

Show societies might benefit from representing rural domains as an exotic ‘other’ by drawing more urban residents through their gates.

Agricultural lobby groups might secure a significant chunk of scarce public resources by arguing that their constituencies are distinct and deserving, identifiable by their farming activities.

While differences obviously exist, so do commonalities. Mounting challenges for all locales posed by global economic and ecological crises suggest value in focusing on the common ground of places and lives.

Inside pavilions, where the fruits of urban and rural gardens and farms are displayed together, an understanding is shared of the value of human effort and knowledge required to grow food.

The produce arranged with care on shelves records creative processes of engaging with dynamic forces encountered inside a paddock, a backyard, a community plot or a suburban nature strip.

Showing produce is a cultural activity that expresses and generates shared values, a commonly held sense of significance and delight in working creatively within living systems to generate food.

As show exhibitors, judges and visitors mill about the displays, they share practical knowledge about food production. The use of judges from rural areas to assess horticultural produce exhibited at urban shows reveals the commonalities of understandings and values that permeate rural and urban domains.

Food growing skills gained in rural or urban areas are celebrated inside show pavilions, regardless of their origins.

Nostalgia and blending of times

Childhood memories of the careful cultivation of vegetables, late-night cake baking and the construction of elaborate food sculptures in the heady anticipation of show day loom large for many contemporary show exhibitors.

It inspires them to participate today, with many hoping to pass on the excitement and joy of show exhibiting to their children and grandchildren.

The nostalgia is often fuelled by an ongoing association of agricultural shows with the past through their inclusion of old-fashioned exhibition categories, particularly in baked goods where the marble cakes, orange cakes and teacakes favoured by past generations of European descendants take pride of place.

For some this sense of nostalgia encourages a reassessment of modern-day living and a desire to engage with the past practices, particularly through a reconsideration of what we value and the time we are willing to devote to certain endeavours such as food production and preservation.

In these imaginings, people used to take the time to do things properly; treating food and domestic duties with care and attention to detail.

Food producing gardeners exhibiting in the Canberra Show talk of the importance of taking the time to inspect each of their plants to develop an intimate knowledge of them and the soil as a way of maximising the chances of show success, but also as a means of connecting to the food system.

This care and devotion of time to perfecting food is also demonstrated in the contemporary cookery section of the show where challenging techniques, exact timing and artistry are on display.

In recent years, a growing focus on the environmental and economic benefits of treating food with care and attention have highlighted the show’s focus on promoting the best of seasonal produce and encouraging the minimisation of food waste through perfecting the techniques of preserving and jam-making.

In this way, agricultural shows enable people to recreate idealised memories of the past through a firm focus on the future.

The introduction of categories for school gardens and the ongoing inclusion of youth exhibitions is a key way in which the shows of today encourage awareness and understanding of the food system as we work towards a more equitable and food secure future.

Growing together

While agriculture and gardening are often represented as attempts to exert human power and control over nature to maximise productivity, the narratives of small-scale growers who exhibit in the Royal Canberra Show attest to the very limits of their capacity to force the land to yield in particular ways at specific times.

Many exhibitors lament the loss of the perfect tomato, zucchini or pumpkin that, having been carefully attended to for weeks to ensure their readiness for show day, split, grew mould or blemished in the final hours due to unexpected rain or bug infestations.

While this can cause heartbreak, the gardeners also express a sense of delight in the challenge and unpredictability of gardening; extracting both joy and disappointment from the vagaries of the weather and the lack of ultimate control they have in their gardening plots.

Such losses and unpredictability seem to make the show day victories even sweeter.

In their gardens, producers gain intimate knowledge of, and work in partnership with, the non-human elements that contribute to food production — from the chemical composition of the soil, to its worms and the climate.

The exhibitors involved in this project indicated a preference for low-input gardening. This was seen as desirable from a health point of view, and viable due to the low ‘eyes to acreage’ ratio. While not always adopting a strictly organic approach, most expressed a desire to return to old-fashioned, pre-chemical gardening.

For many, home food production encouraged intimacy with the food system and the environment, making the growers more attuned to, and respectful of, the multiple inputs and values embedded in their food.

These forms of engagement were juxtaposed with the increasing number of people, particularly in urban settings, disconnected from the food system due to the purchasing of food produced through broadscale, industrial agriculture methods.

Food producing gardening was identified as a key way through which respect for non-human others and the environment could be developed by promoting multiple points of (re)connection to the food system.

Explore more on Urban Farming