This extravagant wedding dress was worn by Lilian Faithfull when she married Springfield employee and family friend William Hugh Anderson at Goulburn in 1898.

Lilian’s dress helps us to explore changes in fashion and the lives women led in the late 19th century. It also reveals the social mores of the Victorian era wedding and its enduring influence on marriage today.

19th century fashion

The style of Lilian’s dress – with its large puffed sleeves, small waist and full straight skirt – was typical of 1890s fashion. Unlike many modern brides, who favour a style radically different from everyday wear, women in the 19th century married in gowns that mirrored fashions of the day. Wedding attire was distinguished by the choice of fabric, the lengthy train and veil and the layers of decorative trim and embellishment.

The desired silhouette of the 1890s was achieved through a fitted bodice, full sleeves, a high neckline and a full-length straight skirt. These pieces worked together to emphasise the essential tiny waist.

In the early 1890s bodice sleeves ballooned to enormous proportions and, while by 1898 the ‘leg-o-mutton’ sleeves had contracted slightly, fullness was maintained by a large puff cupping the shoulder and tapering to the wrist. The skirt became straighter at the front and sides, and tighter around the hips.

These changes were influenced by a growing independence among women and their increasing participation in outdoor activities such walking, riding and cycling. More practical fashion was required, bringing an end to the large bustles and hooped petticoats of previous decades.

Victorian style and accessories

Photos of Lilian on the porch of Springfield homestead in February, at the height of an Australian summer, show a woman wearing a gown that is anything but practical.

The cream duchess satin dress is embroidered with celluloid pearls, glass beads and rhinestones in an arum lily and leaf design. Lilian’s petite waist is accentuated by a full and elaborate bodice with puffed and ruched sleeves, richly embroidered panels and a high neckline swathed with chiffon.

The matching skirt has straight, elegant lines, but is voluminous enough to include a small bustle at the back. Intricate lace – a gift from Lilian’s sister Constance – forms an apron-style trimming around her hips, and is draped over the long bridal train.

Language of flowers

The bodice and skirt are decorated with clusters of wax orange blossoms and tiny fabric lilies-of-the-valley. The Victorian era gave rise to the language of flowers, which was used as powerful form of expression.

Orange blossoms were a symbol of purity, fruitfulness and fecundity. Lily-of-the-valley was a way for Lilian to personalise her bridal display with flowers that signified sweetness and humility. She also wore them as her headpiece, and they were embroidered onto her long veil.

Lily-of-the-valley continues to be a popular choice and was chosen for the bridal bouquet of the Duchess of Cambridge, Kate Middleton, for her marriage to Prince William.

White wedding

Lilian’s choice of fabric colour was a fashionable one, with historic links as well as contemporary relevance. By 1898 the preferred colour for most brides was white — or more accurately, cream or ivory, as silk could not be bleached a pure white without damaging the thread.

In previous centuries wedding dresses came in a range of colours, with white generally being worn by nobility and the wealthier classes. When Queen Victoria married Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg in 1840 she wore an ivory gown and established a widespread trend. Her influence was enormous and the tradition of wearing white is embraced by most modern brides.

In Lilian’s day, white fabric was difficult to achieve and maintain, so it was not only fashionable but also signalled wealth and privilege.

Society wedding

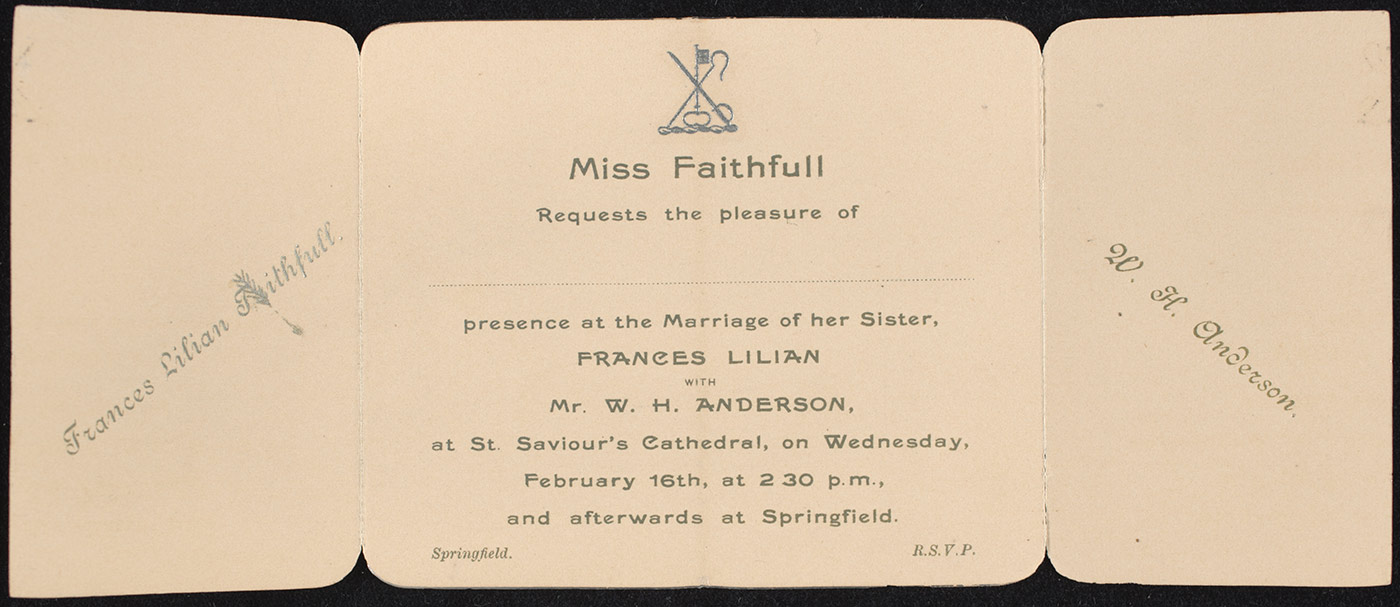

Frances Lilian, known as Lilian, was the youngest daughter of William Pitt and Mary Faithfull. As the daughter of a successful pastoralist and one of the region's oldest families, her wedding attracted considerable attention in the region.

Goulburn and Sydney newspapers described the bride, invited guests and the cathedral decorations in great detail. There was such a large gathering of spectators that the cathedral was completely 'thronged', reported the Sydney Morning Herald.

Following the ceremony the guests and many Springfield station employees travelled to the property where, according to the Goulburn Evening Penny Post, a ‘sumptuous repast’ was enjoyed. The newlyweds left Springfield for a honeymoon beginning in the Blue Mountains before embarking upon a lengthy tour of Europe.

Groom’s attire

Far less importance was placed on the groom’s wedding attire. Lilian’s husband, William Hugh Anderson, was dressed in typical sober contrast. His black frockcoat topped grey trousers, a light-coloured waistcoat, and a white shirt and tie. Pale-coloured gloves and a black top hat completed his outfit.

Unsurprisingly very little of William’s ensemble survived. The Museum’s collection includes a very elegant black top hat — the utmost essential Victorian accessory for men — that belonged to the groom.

Camelot, near Camden

When Lilian and William returned from their honeymoon they took up residence in a house near Camden, New South of Wales, designed by John Horbury Hunt. Inspired by Tennyson's The Lady of Shallot, Lilian named her new home ‘Camelot’.

The three-storey mansion, now heritage listed, was purchased for the couple by the bride’s family. Here they raised their only child, Clarice Vivian, born in 1901.

Marriage was a way of joining powerful families and enhancing wealth and status before and often during the 19th century. However, it seems Lilian married for love. William was ten years her junior, an employee at Springfield, and a man without significant wealth or property.

According to family history, he was much loved by the Faithfulls and greatly admired for his fine equestrian and hunting skills.

Dress alterations

Lilian’s dress had life beyond her wedding day and the version in the Museum’s collection is a modification of the original gown. The large, heavy sleeves were replaced with long, silk organza sleeves featuring a spotted tulle overlay and bands of silk ribbon.

The embroidered pleated panels were adjusted and the layers of chiffon on the bodice yoke and neckline were removed, creating a softer, less structured appearance. The bridal train was also detached and carefully stored with the original sleeves and other accessories.

Alteration of a wedding dress was common in the 19th century. Gowns such as Lilian’s possessed more than just sentimental value. They were expensive creations re-used for court presentations, formal dinners and evening balls. In the months and years following a woman's marriage, it was acceptable and often expected that she was seen in a tastefully restyled version of her wedding dress.

Tragic death

Lilian was devastated by William’s tragic death in 1912.

She dedicated herself to philanthropic activities, helping many in need though the Red Cross Society, the Country Women’s Association, the Returned Services League, and the local council and hospitals.

Lilian was well-known and respected in the Camden community and lived at Camelot with Clarice, until her death in 1948.

When Clarice died and Camelot was sold in the 1970s, Lilian’s wedding gown and and many of her dresses and accessories were returned to Springfield.

The wedding ensemble and associated ephemera are of particular significance to the Museum. This part of the Springfield collection allows us to explore changes in fashion and the lives women led in the late 19th century.

It also reveals the social mores of the Victorian era wedding and its enduring influence on modern day marriages.

In our collection

Explore more on the Springfield–Faithfull family collection