Rabbit tales at the National Museum

A call by the National Museum for responses to objects from the Museum’s collection of rabbit-related objects resulted in tales ranging from the intriguing and illuminating to the arguably ‘tall’.

The Grey Invasion

In 1992 the Museum completed ‘The Grey Invasion – Rabbits, Land and People’, one of our first projects exploring Australia’s rabbit history.

At the Royal Canberra Show, curators set up a display featuring a trap, trapper’s hoe, bait cutter and felt hat from the Museum’s then small collection of rabbit-related items, and invited people to share their stories of rabbits and rabbiting.

Over the three days of the show, many people came forward with rabbit memories, and curator Denis Shepherd later travelled to towns across south-eastern Australia to gather more stories.

One couple from Narrandera, New South Wales explained that they purchased their first new car – a Renault – with money they made from selling rabbit skins.

Another man said that he was able to earn about £100 a week from selling the skins of rabbit he had trapped in the rough country around Inverell during the late 1940s. This was a significant improvement on the £5 a week, plus keep, he could earn as a jackeroo.

One man said that the freezing works where he was employed during the Second World War sold rabbit meat as ‘fresh chicken’ to American soldiers stationed in Australia.

A Ukrainian family related how they were astonished when they arrived in Australia to see photographs captioned as showing a rabbit ‘plague’. They saw them as ‘so much food running around’ and told how all the rabbits in the Moscow zoo had recently been stolen and eaten.

A professional rabbiter told of working in one paddock for seven years without managing to rid it of rabbits, while another explained how he ensured his continued employment by taking a few days off work whenever rabbits were giving birth.

And one man insisted that his grandfather’s method for killing rabbits in rocky country involved peppered carrots – any rabbit that ate the bait would sneeze so much it would smash its head on a rock.

Your stories

Joan McDonald contributed two photographs of her aunt, Violet Abberton, to the National Museum’s 1992 ‘Grey Invasion’ research project. This project invited people to share their stories and experiences of rabbits.

In the photographs, Joan’s aunt Violet demonstrates two commonly-used methods for dealing with rabbits in rural areas – shooting and warren destruction.

Joan’s letter reveals how, 70 years on, having migrated into urban landscapes, rabbits continue to present a challenge to land (and garden) owners. She wrote:

I have enclosed two photos of my aunt, taken near Bathurst NSW in the 1920s.

[I]t seems that the ‘grey invasion’ may not yet be over. My husband and I are building a retirement home at Sanctuary Point NSW where our neighbours-to-be tell us amazing stories about their war against the local rabbits, who are currently undermining their houses and destroying their garden plants. Shoalhaven City Council, they claim, have recently lost a whole planting of shrubs along the waterfront at nearby Vincentia, on Jervis Bay, due to rabbits and are planning to eradicate them by means of toxic gases.

Ken Roberts contributed this photograph and story about his father Jack Roberts to the National Museum’s 1992 ‘Grey Invasion’ rabbit research project.

Ken’s story illuminates some of the ways Australians have experienced rabbits – welcome source of income, readily available food item (not just for human consumption!), and family companion.

In a letter to the National Museum, dated 19 November 1992, Ken wrote:

Jack Roberts age 15, 1943 at Nuntin Road, Boisdale, Victoria on his parents share farm. Between morning and night, milking and farm work he and [his] brothers would check the rabbit traps set the previous day and use ferrets to catch rabbits. The average catch was 15 to 20 pair per day. Most of these were transported 1½ miles [about 2.4 kilometres] down the road to Ridley’s corner to sell to Harold Symonds for 2 to 3 shillings a pair. The picture shows the rabbits (9 here) as carried across the handlebars – they were also strung over the middle bar. Some nice young rabbits were kept for the family to eat and sometimes boiled up for the chooks. The skins of these were hung over frames and then sent to Melbourne by train to sell to Goldsborough Mort and J. Kennan and Sons. The price was about 5 shillings a pound. He was paid 10 bob a week and keep to work on the farm and the extra rabbit money helped him save up for his bike amongst other things. His mother had a pet magpie, rabbit and dog and he can remember how she had them all playing together happily.

Judith Anketell of Ardross, Western Australia, contributed this short story to the National Museum’s 1992 ‘Grey Invasion’ rabbit research project.

Judith’s story considers both dark and light in the relationship between humans and rabbits: a farmer’s pleasure at the brutal efficiency of poisoned baits sits uncomfortably against the writer’s fond memories of Beatrix Potter’s endearing characters in the Peter Rabbit books.

The farm was in the S[outh] W[est] of West Australia. In hilly country, with a high rainfall it was suitable for dairying and potato-growing. Most of my school holidays were spent there in the mid-thirties. This friendship between the two families – mine a country town one – began in the Depression. My family lost everything when the Bank my father was manager of, went bust. The farm family saw what a difficult time we were having , so offered to have me for the holidays to help us manage and also to be a friend to their three children.

I liked the farm and the family. Except the farmer. I was scared of him but I never said anything about this to anyone. So one May holidays, as a shy 9 years old, I was again there amongst the hills and cows… and the rabbits. They’d always been there but this time it was pointed out to me how many more of them there were, after a good summer and autumn. At dusk you could see them sitting still or scurrying about the paddocks as you stood on the verandah of the house. Once the farmer went to the town and bought some poison (strychnine). Then he and the farm labourer, with help from his 10 year old son Ted, cut up hundreds of apples kept from last season’s crop in their home orchard. They mixed the poison and apples and set out with the tractor that afternoon. A trail of poison apple was laid all over the hilly paddocks one after the other and especially near the burrows. Down by the creeks and in the gullies there grew a lot of bracken with fascinating bright green curled-up fronds. After dinner we were all told to go to bed as we had to be up early to get the rabbits. I had no idea what this involved but was happy to be part of the plan.

At 5a.m. I was woken and told to get dressed in warm clothes and come to the kitchen. There I was given a mug of hot cocoa and a size too big wellington boots. We set off them, he farmer, his wife, his eldest son and daughter, the little boy and the farm labourer. There was an air of excitement amongst us and for me mystery, as with hurricane lanterns we made our way in the dark to the milking sheds. Here we seven divided into 3 parties. The farmer, Ted and me were together. I knew I wouldn’t like that much. The farmer was taciturn and unfriendly and I knew I’d have to do my best or be humiliated.

The sun was just rising. Our breath made ‘smoke’ as we breathed out. It was very cold and there’d been a heavy dew so the grass and stubble was soaking wet. When through the first gate I was told to ‘pick ‘em up and carry ‘em to the pit’. The other two set off. At first I couldn’t see anything , but I picked up the apple trail and followed it expecting to see rabbits. Soon I was shouted at ‘Look over there can’t you, PICK ‘EM UP’. The rabbits died away from the trail as they made off to their burrows, so it was no good sticking to that. You had to veer off to right and left looking for the bodies. I found them. Stiff, cold and wet or warm and newly dead. I was shocked at the sight and the job. The poor things, they were only living rabbit lives. All this slaughter around me was awful. My sensibilities were jarred. Had I not been brought up on ‘Peter Rabbit’? Flopsy, Mopsy and Cottontail too and their Mother? Such charming whimsical creatures.

There was not time for reflection though or of nursing any feelings. There was a grim job to be done – alone. I picked up the first rabbit by the back legs as I saw others do. I was surprised at how heavy it was. Then a couple more small ones and that’s all one hand could carry. So I got 2 or 3 more in the other hand and set off with my six dead, wet rabbits for the deep pit where they were to be thrown. I tramped up the bare paddock in my large wellies with my unusual burden. Then down the other side to the pit. Everywhere were rabbits, hundreds of them, stretched out in all kinds of positions as death struck them. Paws up in the air [,] on their backs or sides, eyes open or closed, white powder-puff tails, now matted, and sometimes blood oozed from their noses. I started again near the pit, and this was in the bracken area. Some of the fronds were nearly as high as me. As I searched underneath for bodies, the fronds dripped on me and the fur was wetter. Another load was soon picked up and taken to the pit. A trip in the other direction now. More bracken, I searched diligently carrying 4 bodies, when the gruff voice of the farmer called out ‘Look what you’re doing. You’ve missed that BIG BUCK.’ I meekly went to where he was standing pointing furiously. I stared at it transfixed by its size. ‘PICK IT UP’. I did so murmuring ‘Sorry, I didn’t see it’. I felt small and demeaned, I’d tried so hard. My next dilemma was, could I carry a sixth rabbit as well as 4 and the big buck? I decided I’d better or I’d get what-for again. It was a real struggle to make the pit that time. Ted seemed to be having no trouble – well, I supposed that was because he was a boy. Probably the bare paddock, I thought, rather than the gully would be my best bet. The rabbits were easier to see. They still had to be picked up and then woulnd’t the farmer see I was doing my utmost? More forays, more wetness, my hands were frozen. I tripped over stones because the [boot] toes were not where my toes were. Once I tripped over and fell on my load of rabbits. Oh, how horrible. They were so soft and wet, and I felt it indecent to fall on them. Repulsive too, I was covered in blood and mud. The sun rose higher, and my clothes began to steam. How many more were there, when would we stop, who would milk the waiting cows? Or was this holocaust collection more important than anything else? Nobody spoke. Where was the farmers wife, she was more friendly, I wished I could see her.

Sometimes Ted or the farmer found a live rabbit, or kittens who’d left the burrow to seek their mother. Then they took them to a tree and holding them by the hind legs, bashed their heads against it. Their necks were broken with a sickening crack. I couldn’t look after the first time. Soon I forgot about being sorry for the rabbits as I was feeling increasingly sorry for myself. How long were we to do this – all day? What about breakfast? My arms ached, I was cold and miserable. Dimly I wondered how I came to be doing this awful job in what were supposed to be happy holidays. I was aware though that the whole thing was necessary for the survival of the farm and its dependents.

At last the call was made to stop. As I looked in the pit for the last time, that mass grave of furry bodies, hundreds of them, is a sight I will never forget. Breakfast thankfully was a fairly cheerful affair (as long as we children behaved). But at least the farmer had a grim smile on his face., as he estimated we’d picked up between 800–900 rabbits. He felt successful.

The warm food and a change of clothes soon made my childish spirits rise. I was too young to realise the why of this murderous morning. But anyhow no one had attempted to explain it to me. I learned about rabbits, and I learned about the human pecking order. A most unpleasant experience.

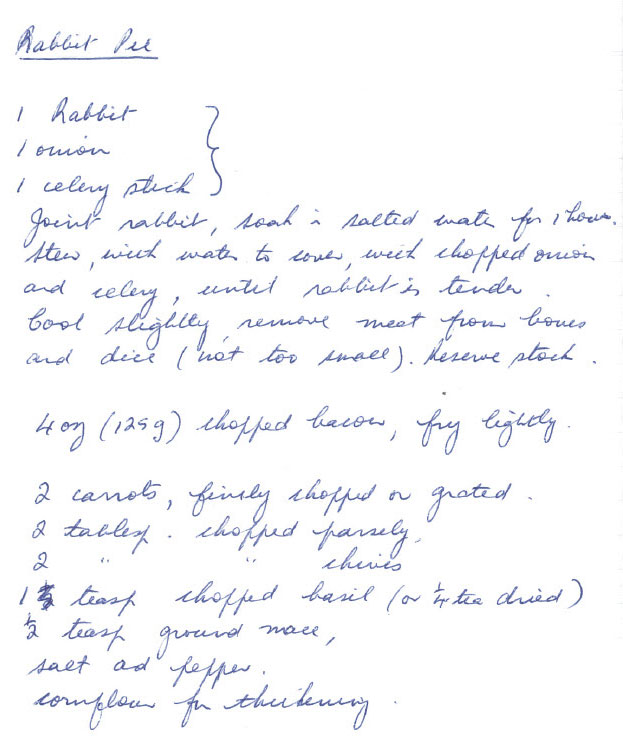

This contribution is from Mrs Joan Bell of Exeter in the Southern Highlands of NSW, who wrote: ‘I am forwarding a recipe for rabbit pie. My grandchildren consider it quite delectable. It was very popular in my childhood.’

Rabbit pie

1 rabbit

1 onion

1 celery stick

Joint rabbit, soak in salted water for 1 hour. Stew, with water to cover, with chopped onion and celery, until rabbit is tender. Cool slightly, remove meat from bones and dice (not too small). Reserve stock.

4oz (125g) chopped bacon, fry lightly

2 carrots, finely chopped or grated

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

2 tablespoons chopped chives

1 teaspoon chopped basil (or ¼ teaspoon dried)

½ teaspoon ground mace

salt and pepper

cornflour for thickening

Place all ingredients, including rabbit meat, into saucepan with some of the stock. Use as much stock as necessary to prevent sticking. Bring to boil and simmer a few minutes. Mix a little cornflour (try a tablespoon first) with a little water. Add to mixture in saucepan and boil a couple of minutes. Let cool.

Line a greased pie plate with shortcrust pastry (or frozen sheets, thawed - I have used puff pastry and find it very nice, especially on top). Fill with rabbit mixture. Cover with pastry and bake in a hot oven (450˚F) about 30 minutes until golden.

Serves 6

Mrs Rita Wilson of Mildura, Victoria, contributed this letter to the National Museum’s 1992 research project about rabbits in Australia. Her story highlights how rabbits created opportunities as well as frustrations for those who lived and worked on the land.

Mrs Wilson wrote:

Dear Madam,

Letters to the Editor, in Sunraysia Daily Feb. 22nd ’92 re rabbits.

My recollections start 1930 depression & maybe a few years before, in the Mallee region – north west Victoria. No doubt many families would have starved, but for the ‘underground mutton’ – as it was often called, to eat & sell.

My mother had many ways of cooking same. First remove tailbone (this was supposed to take away rabbit taste) – then soak in salt & water for an hour or so, then dissect for stew, etc. Our favourite was, boil to near cooked – then roast in oven, seasoned & wrapped in bacon – home cured of course. The water would be used for soup and stock later. Too poor to buy bullets, traps were set & visited twice daily. It was very heavy work walking with traps over shoulders across sandy areas (where rabbits liked mainly to burrow) – to begin with only skins could be sold – at 4 pence up to 1/- for bucks. Rabbits were also used to feed to pigs as another avenue of income.

Skinned & rejected rabbits would be boiled up in kerosene tins – maybe with wheat added & fed to pigs. Once rabbits were well cooked, the bones came free & would be taken out before feeding to pigs.

As more rabbiters made more volume of rabbits – pickup trucks entered most areas (rabbits were checked for bruising, paired and hung across a f[ence] wire after being gutted. They then went to closest ice works – as problems presented there – eventually refrigerated trucks stopped along the highway. Rabbiters given time usually very early a.m. so it was a[n] early start to go around traps. Refrigerated trucks would then go to a major centre, such a[s] Mildura.

Approx. 1950 my husband & I purchased a farm next to big desert in the mallee. It was a very dry period & rabbits had to come into our one small dam for water. We netted the dam with a few entrances for the rabbit to get through a funnel shaped hole. The rabbit could find [the] entrance, but as it was so narrow at the other end of [the] funnel, they were trapped in the enclosure.

Our first try netted 250 & husband (a city boy back from [the] RAAF) bravely faced the task. As told, he grabbed one & rung its neck and threw it outside the enclosure, then a second one. Imagine his dismay when each dazed bunny jumped up & ran away. After that, he made sure of the ghastly deed by putting boot on head first, to get stronger pull. To start with, we netted every 2nd night. Had to remove enclosure daily for stock to water. Usually 200 to 200 a night.

The trappers were very diligent, would ask permission, then ‘work it’ until most rabbits were caught. Farmer would then rip burrows up – maybe first ferreting or fumigating same. A close watch would be kept of the areas to see no fresh openings. Greyhound dogs were also used, but they caused bruising.

Trappers would gut & pair rabbits – then hang over a wire, or mallee stick, suspended between forked sticks – then would cover all with a hessian sleeve, or screen, to keep out flies, while waiting for pickup trucks.

These are some of my recollections.

Yours sincerely,

(Mrs) Rita Wilson

GJ Skillman of Ulladulla, New South Wales, wrote to the National Museum in 1992:

Being a veterinary officer within the State Department of Agriculture for 35 years I had the privilege of working in my early career with some of the old Stock Inspectors attached to the Pastures Protection Boards and heard many stories of the hordes of rabbits that were seen in the early part of this century. Heavy infestations in the late 40s & early 50s were “light” in comparison according to the Stock Inspectors.

Sincere good wishes,

[signed]

GJ Skillman BVSc

Pastures Protection Act 1902

The New South Wales Pastures Protection Act of 1902 required property owners and occupiers to be assessed for the payment of rates for – among other things – the construction of rabbit-proof fences and ‘machinery, plant or substances for the destruction of rabbits’.

Landowners were required to maintain rabbit-proof fencing on their lands and ‘... to suppress and destroy, by all lawful means, at his own cost, and to the satisfaction of the [Pastures Protection] board, all rabbits and noxious animals which may from time to time be upon such land … ’.[1]

In 1906 the Act was amended to ‘make further provision for the encouragement of the erection of rabbit-proof fencing … ’.[2]

At that time, the need to actively control the spread of rabbits was considered imperative, and those proven to have neglected or shirked their responsibilities were liable to receive a significant fine which increased with subsequent violations.

Notes

In our collection

In November 1992 Mrs Kay Sage of Canberra, a childhood patient of paediatrician and myxomatosis advocate Dame Jean Macnamara, contributed this humorous anecdote to the ‘History of Rabbits/ Rabbiting in Australia’ research project.

Dame Jean Macnamara (1899–1968) was a physician and medical scientist who encouraged the Australian government to pursue the myxoma virus as a biological means of rabbit control. Prime Minister Robert Menzies couldn’t remember the name of the disease, ‘myxomatosis’, so Dame Jean told him this story to help him recall it:

‘A small rabbit was sitting rubbing its two front paws together. When asked what it was doing the rabbit replied, “Mixing my toesies”.’

Curator Kirsten Wehner explains her fascination with a small but disturbing object that tells a much larger story about rabbit control in Australia.

In our collection

In January 1993 Sue Cook from Bendigo, Victoria, wrote to the Museum about her father’s rabbit skin rug and the significance of the rabbit industry in northern Victoria before the introduction of myxomatosis:

The ‘rabbit skin rug [was] made from 36 skins caught by Alf Morrison around 1945, for his wife. The skins were sent away to be tanned, dyed, stitched together and mounted on brown felt … . The rug has been used as a quilt and as a throw-over for a couch. It is still currently in use … .

McMillans is a small district near Cohuna and my father’s farm was part of the district. The local hall was built with voluntary labour and money raised from rabbit drives by farmers in the community. This was just after the Second World War and the money was raised over two years. The rabbit drives were conducted between milkings (a dairy farming district) and groups brought their own equipment (rabbit netting wire and chutes made with steel posts). Portable frames were made for the yards and people used sticks to shoo the rabbits into the catching area. The rabbits were caught in the Pyramid Creek area. The rabbits were gutted but not skinned and were hung in pairs on a pole. This was all covered in hessian to keep the flies off and [was] collected immediately by freezer truck (‘if not collected immediately, they went white and were no good’). Approx. 600–1000 per drive went to the freezers.

In our collection

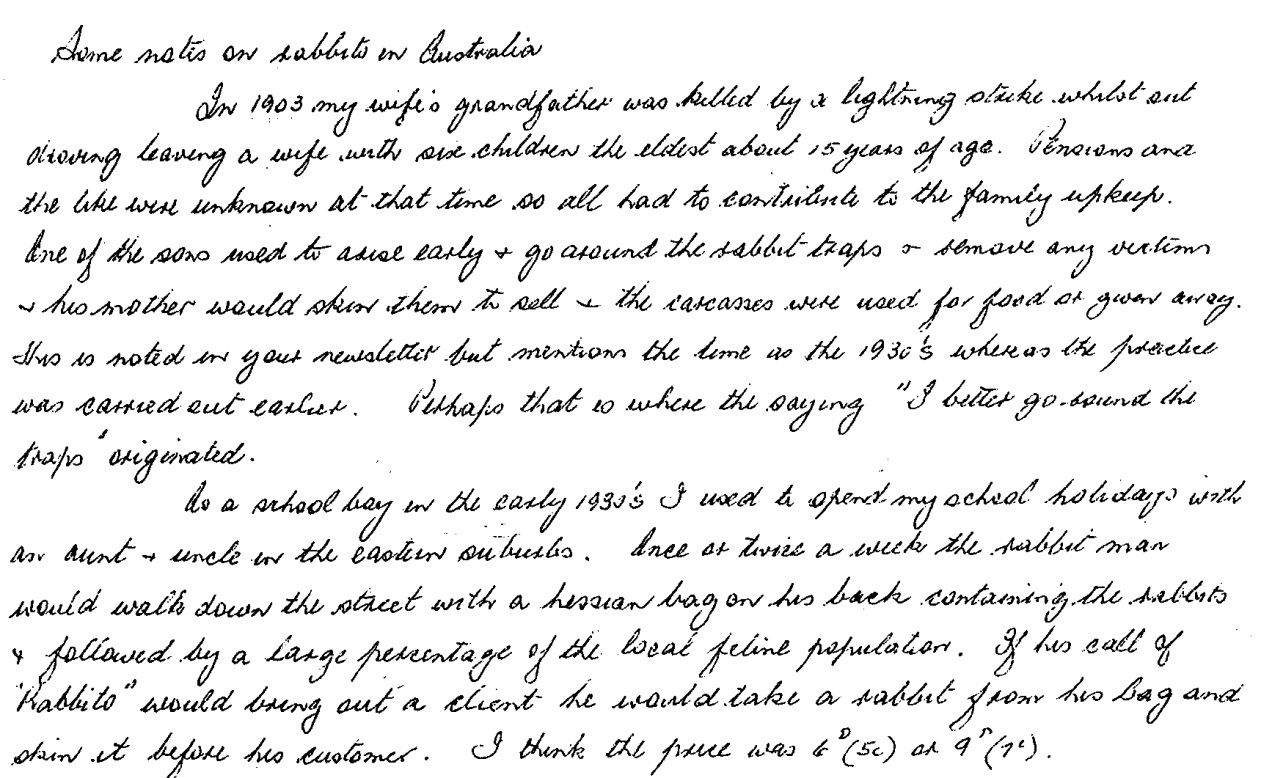

In July 1992 Mr Hanley of Caringbah, New South Wales, sent to the Museum the following ‘notes on rabbits in Australia’, in which he outlined rural and urban uses of rabbits:

In 1903 my wife’s grandfather was killed by a lightning strike whilst out droving leaving a wife with six children, the eldest about 15 years of age. Pensions and the like were unknown at that time so all had to contribute to the family upkeep. One of the sons used to arise early & go around the rabbit traps & remove any victims & his mother would skin them to sell & the carcasses were used for food or given away … Perhaps that is where the saying “I better go around the traps” originated.

As a school boy in the early 1930s I used to spend my school holidays with an aunt & uncle in the eastern suburbs [of Sydney]. Once or twice a week the rabbit man would walk down the street with a hessian bag on his back containing the rabbits & followed by a large percentage of the local feline population. If his call of “Rabbito” would bring out a client he would take a rabbit from his bag and skin it before his customer. I think the price was 6 d (5c) or 9 d (7c).

Explore more on Rabbits in Australia