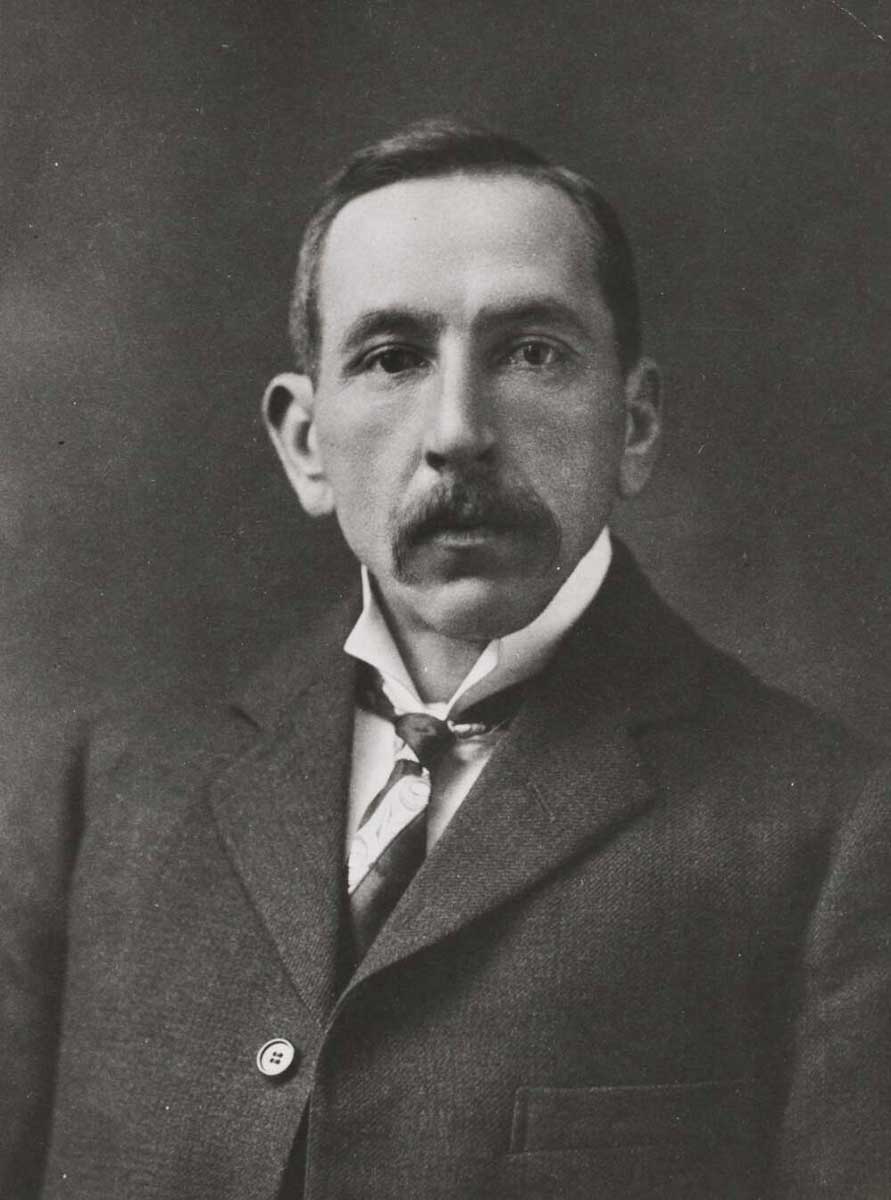

Australia’s Prime Minister three times

27 October 1915 to 14 November 1916, 14 November 1916 to 7 February 1917, 17 February 1917 to 9 February 1923

Holding the record for the longest-running continuous service to parliament, Billy Hughes spent 58 years in state and federal politics.

Hughes was a member of federal parliament from the beginning of Federation in 1901 until 1952. Prior to that he spent seven years in the NSW Parliament. He was Prime Minister for seven-and-a-quarter years.

While Prime Minister during the First World War, he became known as the ‘Little Digger’ and was an advocate for compulsory military service.

During his long, stormy career he chopped and changed his political ties, representing four different parties, three of which expelled him. Hughes was also known as one of the fastest political wits in the history of the parliament.

Hughes' beginnings

William Morris Hughes (known affectionately as ‘Billy’) was born in London, UK, on 25 September 1862. He was the only child of Welsh immigrants to London. His father, William Hughes, was a carpenter at the House of Lords and a deacon in London’s Welsh Baptist Church. His mother, Jane Morris, was a domestic servant, and died when he was seven.

After his mother’s death, the young Hughes lived with her family at Llandudno, Wales, and attended the local grammar school until he turned 14. He spent the next five years as a pupil teacher at St Stephen’s Anglican School, Westminster, where (he later claimed) his school inspector, the poet and critic Matthew Arnold, encouraged him to read widely.

Hughes migrated to Brisbane in 1884 and, after failing to find a teaching position, worked in a great variety of jobs including railways tally clerk, rock breaker, boundary rider, blacksmith’s striker, well sinker, farm labourer, swagman and cook on a coastal ship. This last job was probably how he arrived in Sydney around 1886.

In 1886 he married Elizabeth Cutts, with whom he had seven children. In 1891 he and Elizabeth opened a small mixed business in Balmain, Sydney, which, among other things, sold books and political tracts. He also worked as a door-to-door umbrella repairer to survive.

Because he was attracted to radical politics, Hughes joined the Socialist League and became a fiery street corner orator.

Hughes' time in Australian unions

In 1893 Hughes became an Australian Workers’ Union organiser, travelling around western New South Wales to sign up members and establish Labor Electoral Leagues. (These were the forerunners of Labor Party branches.)

Following informal work as an adviser to the Wharf Labourer’s Union during the maritime strike of 1890, he became the union’s secretary. He then founded the Trolley, Draymen and Carters’ Union, and became its president. He gained awards for both unions, including minimum pay rates and the eight-hour day. In 1902, Hughes formed and led the Waterside Workers Federation of Australia.

Hughes was elected to the New South Wales Legislative Assembly as the Solidarity Labor Party candidate for Lang, Sydney, on 17 July 1894. Over the next six years, he acquired a reputation as a clever political strategist and persuasive debater, whose witty and sharp speeches could fill the House.

Hughes' entry into federal politics

Hughes became the leading Labor advocate for Federation and for a strong central government. He was elected as Labor candidate for West Sydney at the first federal election on 29 March 1901. He held this seat through the next five general elections.

While a politician, Hughes also studied law and was admitted as a barrister in 1903. He subsequently represented union clients.

Hughes held many portfolios. He was appointed Minister for External Affairs in John Christian Watson’s short-lived Labor government, Attorney-General in Andrew Fisher’s three Labor governments (1908–1909, 1910–1913 and 1914–1915), and Deputy Prime Minister in the latter two.

Elizabeth had died in 1906, and Hughes married Mary Campbell in 1911. They had one child together.

Prime Minister William Hughes

Hughes was Deputy Leader of the parliamentary Labor Party from 1907, and so succeeded Fisher as Prime Minister on 27 October 1915 when Fisher retired. Committing himself to a vigorous ‘win-the-war’ policy, he proved to be a tireless wartime Prime Minister.

Wartime and conscription

Hughes travelled to London in early 1916 to represent Australia in UK war Cabinet meetings. He was welcomed enthusiastically wherever he went. He was offered a Cabinet position because of his effective advocacy of ‘Total War’.

He donned a slouch hat to visit Australian troops serving in Europe and revelled in the nickname they bestowed upon him – ‘the Little Digger’. He gave undertakings to the UK Government to boost military recruitment in Australia.

Hughes returned to Australia on 31 July 1916, and began advocating compulsory military service to lift recruitment numbers. He announced a referendum on the matter on 30 August. The New South Wales branch of the Labor Party expelled Hughes on 4 September for promoting conscription.

On 14 September he introduced into federal parliament legislation for a referendum on conscription, which was passed with opposition support. Six ministers, including his deputy, Frank Tudor, resigned over the issue.

The referendum on 28 October 1916, which followed bitter, divisive campaigns by both pro- and anti-conscriptionists, rejected Hughes’ conscription proposal by a slender majority.

On 14 November 1916 a meeting of the federal parliamentary Labor Party caucus debated a motion to dismiss Hughes from leadership. Hughes and 23 supporters walked out of the meeting and quit the party. Frank Tudor was elected leader in his place.

Formation of the Nationalist Party under Hughes

Hughes resigned the prime ministership on quitting the Labor Party, but the Governor-General (RC Munro-Ferguson) immediately recommissioned him to form a new ministry from among his followers.

He then continued as Prime Minister, heading a minority government of his group, which called itself the National Labor Party and governed with the support of the former Liberal opposition.

Hughes’ National Labor Party and the Liberal Party merged as a new party, the Nationalist Party. This new party won government at the general election on 5 May 1917. Hughes also switched to the seat of Bendigo at this election.

Still determined to win the debate on compulsory military service, Hughes instituted a second conscription referendum for December 1917. This referendum resulted in an increased ‘No’ vote.

In April 1918 Hughes and former Prime Minister Joseph Cook, then Minister for the Navy, left Australia for London to attend the Imperial Conference. Hughes remained away for 16 months, staying on to attend the post-war Versailles Peace Conference, the treaty of which he signed on 28 June 1919 on behalf of Australia.

At the Versailles Conference in 1919, Hughes aligned Australia with nations demanding heavy reparations from Germany. He was in frequent conflict with President Woodrow Wilson of USA, the leader of a moderate faction.

In one famous exchange, Wilson, trying to cut Hughes down to size by alluding to Australia’s minor conference role, asked him who he represented. Hughes replied that he spoke for ‘60,000 war dead’ – a pointed reminder that though Australia’s population numbered less than a twentieth of that of the USA, its tally of war dead was more than half the USA’s.

He succeeded in securing Australian control of Germany’s colonial possessions in New Guinea and the adjacent archipelagos.

Hughes' decreasing popularity

After returning from Versailles, Hughes progressively lost control over his government. His Nationalist Party lost their majority at the general election in December 1919 and had to rely on support of the newly emerged Country Party (CP), which proved antagonistic to Hughes.

The Nationalists were increasingly torn by internal dissent, much of it arising from dissatisfaction with Hughes’ leadership. At a general election on 16 December 1922 Hughes switched again to the New South Wales seat of North Sydney (and held it through the next 10 general elections).

During this campaign five Victorian and South Australian Nationalists fought on the ‘Hughes Must Go’ platform; the party lost further ground. During the next two months, as the Nationalists and the CP sought some agreement with each other, the CP made it clear that any coalition arrangement would depend on Hughes’ departure as Nationalist leader.

Hughes resigned as Prime Minister on 9 February 1923, and recommended to the Governor-General the appointment of Stanley Melbourne Bruce as his replacement. Bruce was commissioned that day.

Hughes' later political life

In 1929 Hughes precipitated the fall of the Bruce-Page coalition government by voting with Labor against the government on a censure motion. Bruce then expelled Hughes from the parliamentary Nationalist Party on 22 August 1929.

Shortly after, on 10 September, Hughes moved the deferral of an arbitration bill, which Labor and four other rebel Nationalists supported, effectively bringing down the government. Hughes hoped Labor would invite him back as leader, but bitterness within the party over the split of 1916 was too strong for that to happen.

In October 1930 Hughes launched a new party – the Australia Party – which soon withered away after polling poorly in New South Wales state elections later that month. He joined the United Australia Party (UAP), formed under JA Lyons’ leadership.

The UAP defeated James Henry Scullin’s Labor government at a general election on 19 December 1931 and assumed office on 6 January 1932.

In the UAP's government Hughes represented Australia at the League of Nations assembly in 1932. He became Minister for Health and Repatriation in 1934, and campaigned against the falling birth rate under the slogan ‘Populate or Perish’.

He was also Vice-President of the Executive Council 1934–1935 and 1936–1937; Minister for External Affairs 1937–1939; Attorney-General again 1938–1941; Minister for Industry 1938–1940; Minister for Navy 1940–41; and Member of War Cabinet 1939–1941.

Hughes' time in the United Australia Party

After Lyons’ death in April 1939, Hughes, now 76, was narrowly defeated for the UAP leadership (and therefore the prime ministership) by the party’s rising star, Robert Gordon Menzies, of whom he was highly critical. He once commented that in his opinion, ‘Menzies couldn’t lead a flock of homing pigeons’.

When Menzies resigned the prime ministership on August 1941, Hughes became the UAP leader, but not prime minister. This position went to CP leader Arthur William Fadden. Hughes retained the UAP leadership until August 1943.

When John Joseph Curtin’s Labor government took office in October 1941, Hughes worked cooperatively with Curtin as a member of the Advisory War Council. He opted to remain a member of the council after the UAP withdrew from it in 1944, for which the UAP expelled him.

He joined the newly formed Liberal Party in 1944, and remained a back-bencher after Menzies led the party to victory at the December 1949 general election. At this election, following electoral redistribution, he took the seat of Bradfield, New South Wales, and retained it at the 1951 election.

He had thus been elected at all 21 general elections in the half century from 1901 to 1951.

Hughes' record of service

At his death in 1952 Hughes had spent over 58 continuous years as a member of parliament, almost 51 of these in federal parliament. He was the last politically active member out of all those who had entered parliament in 1901.

His period of membership remains a record in Australia. He has been the only one to have been Prime Minister on both sides of politics – Labor and non-Labor.

Hughes died in Lindfield, New South Wales, on 28 October 1952. His state funeral in Sydney was one of the largest Australia has seen. Some 450,000 spectators lined the streets to watch the passage of a flag-draped coffin on a gun carriage accompanied by a three kilometre-long procession of mourners.

Legislation passed under Hughes

Hughes’ well-known support for conscription and his attempts at its introduction required the passage first of the Military Service Referendum Act 1916, after which the referenda were put and failed on both occasions.

Hughes’ second government (1917–1919) introduced and had passed the following legislation.

- The Australian Soldiers Repatriation Act 1917 established a Repatriation Commission to regulate assistance and benefits to returned soldiers and to the widows and children of soldiers killed.

- The War Service Homes Act 1918 provided mortgage and rent assistance to returned servicemen.

- The Electoral Act 1918 established preferential voting and is still in force under this title, though many times amended since 1918.

- The fourth Hughes government 1919–1923 repealed the War Precautions Act.

Other important legislation included:

- The Air Navigation Act 1920 regulated civil aviation, as a result of Australia’s agreement to the international convention held in Paris in 1919 – a use of the ‘external affairs’ power.

- The Butter Agreement Act 1920 was early legislation to regulate the marketing of primary produce, and one of the first of many similar primary industry marketing acts.

In our collection