Yulara is a tourist village established in the late 1970s alongside Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in Central Australia, more than 300 kilometres south-west of Alice Springs. The village has a supermarket, restaurants and cafes, all reliant on regular food deliveries by truck and aeroplane.

Across the arid plains of red sand and spinifex that extend beyond the village, the local Yankunytjatjara, Pitjantjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra people, known as Anangu, hunt animals and gather bush fruits and vegetables. Pastoralists raise beef cattle on vast stations.

Lizard sculpture by Billy Wara

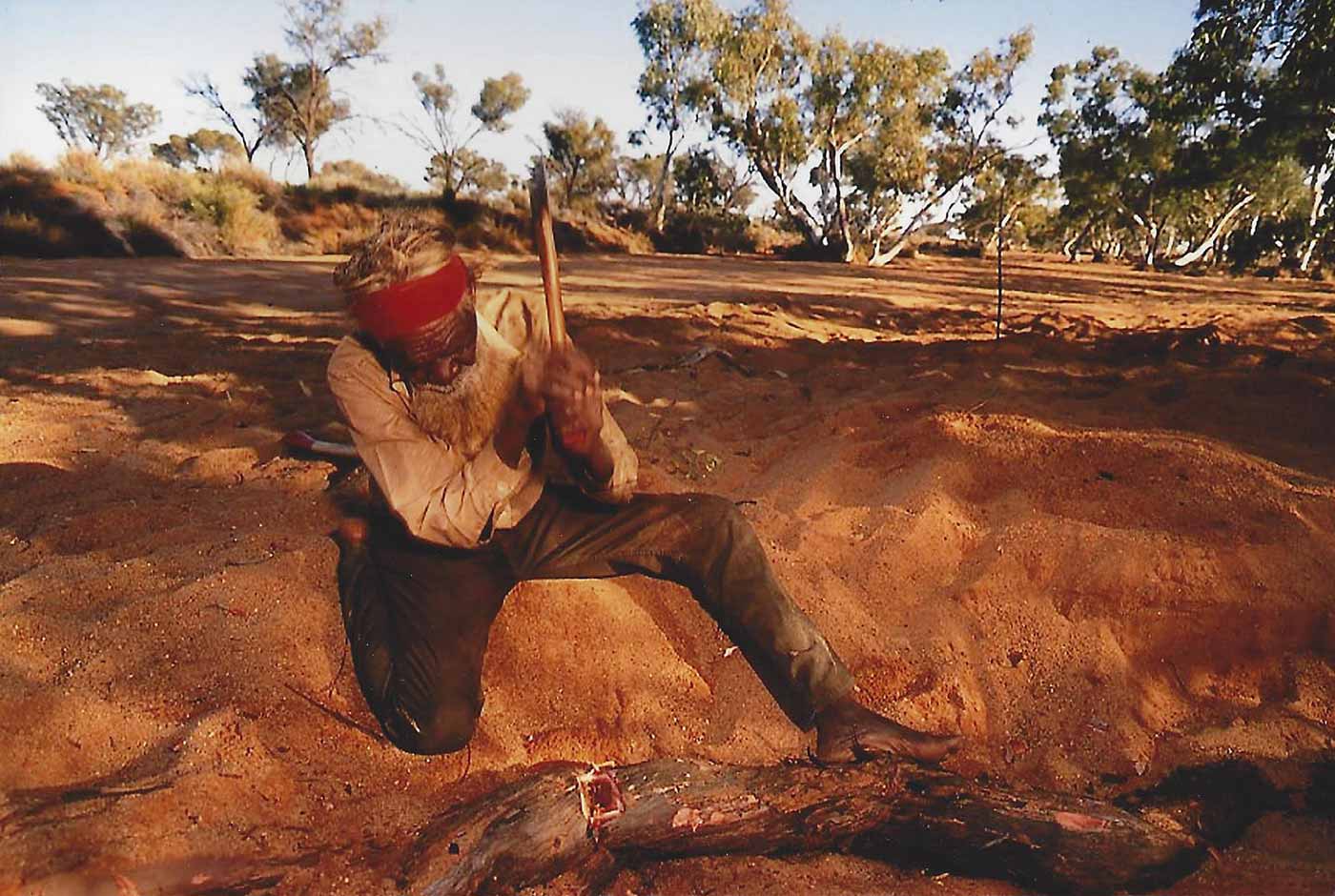

Billy Wara, an esteemed Pitjantjatjara custodian and artist, carved and decorated this red gum sculpture of a ngintaka, or perentie lizard, in the early 1980s.

Born in about 1920, Wara worked for decades in the pastoral industry, building fences, droving cattle, shearing sheep and digging wells. A talented carver of traditional hunting tools, he later used these skills to create wooden ngintaka sculptures. Wara used fencing wire to burn patterns into the wood.

The perentie is muscular and beautifully spotted and, as Australia’s largest lizard, can grow more than 2.5 metres long. Wara was responsible for maintaining traditional stories and ceremonies about a ngintaka creation figure who stole a particularly fine-grained grinding stone, prized for the high quality flour it produced.

Perentie flesh is highly valued by Anangu because of its high fat content, a rare quality in desert game. Anangu in the Uluru region hunt the lizards and roast them on open fires.

Tourism and art

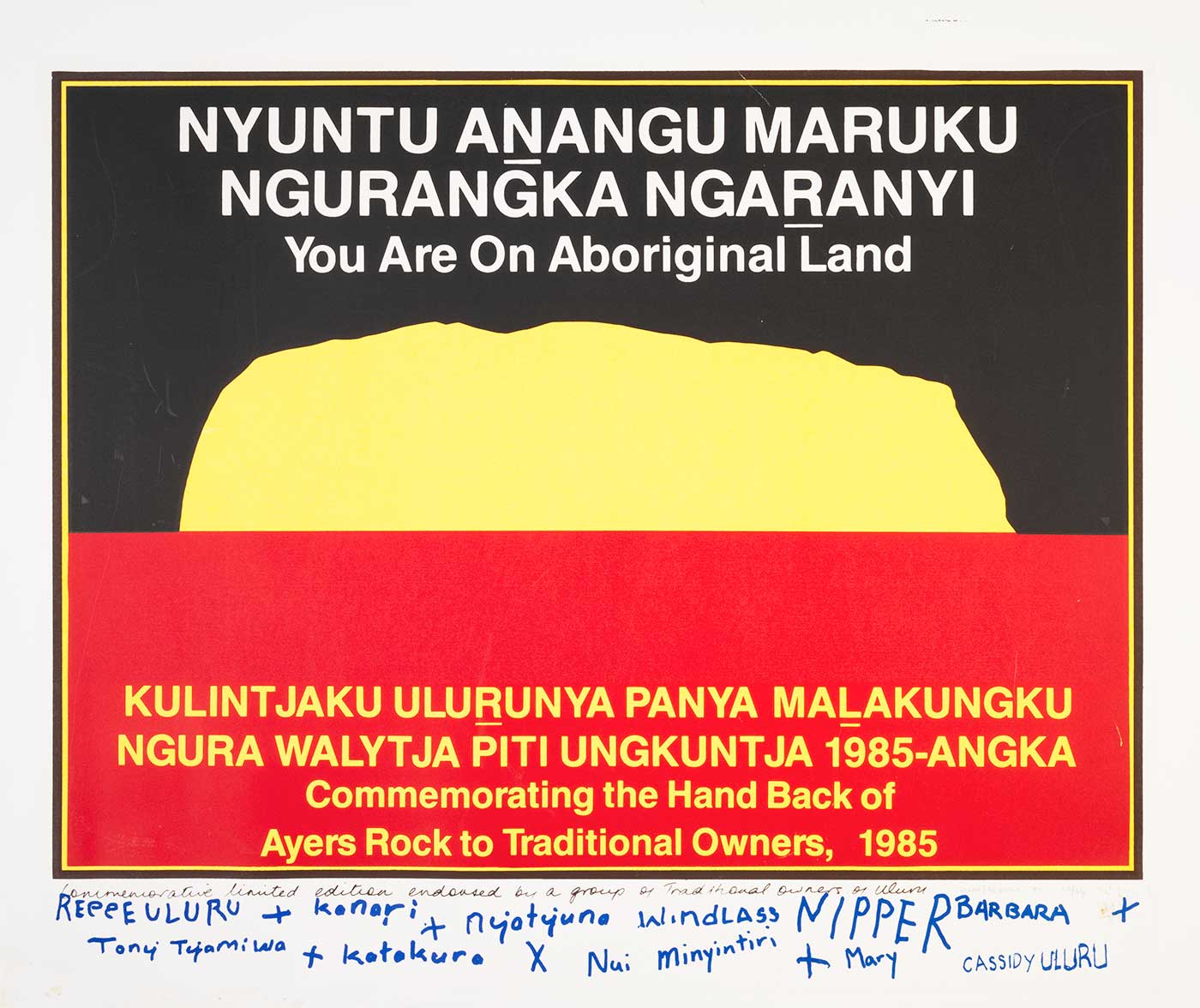

Throughout the 1960s and into the 1980s, as the tourist industry made major inroads into the Uluru region, the sale of carvings and other artworks and artefacts gave traditional owners an independent source of income that helped them live and travel through their country.

In the early 1980s Billy Wara helped establish Maruku Arts at Uluru.

The largest Australian art centre owned by its Aboriginal artists, Maruku collects and sells artworks produced by about 900 Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and Ngaanyatjarra artists from communities across the south-east and western parts of Central Australia.

Revenue from the production of carvings and other artworks helped traditional owners to engage in political struggle for land rights that culminated in the return of Uluru and surrounding lands in 1985.

Billy Wara video

In the 1990s arid zone ecologist Jake Gillen worked alongside senior Anangu men and women at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. Amidst sculptures acquired by the National Museum from Maruku Arts, Jake remembers Billy Wara and shares his understandings of food systems in the Uluru region.

Arid zone ecologist Jake Gillen remembers Pitjantjatjara custodian Billy Wara and shares his understandings of food systems in the Uluru region.

JOE GILLEN: Well, my role at Uluru was principally as an ecologist managing natural and cultural values of the park. A long time ago now, so from about 1994 through to 2000.

I worked in a joint management situation with senior Anangu, senior men and women, very much in a ngapartji ngapartji way, which means I learnt from them and they learnt from me.

So it was a respectful relationship that we had.

Billy Wara was a very tall, elegant, dignified man; very gentle, very quiet but a wonderful artist. And readily identifiable in the community because he used to walk with his very tall dog, papa wara papawarra, 'papa' meaning 'dog' and 'wara' meaning 'tall again'.

He was a senior law man and his main Tjukurpa, mythological story, related to the ngintaka or the perentie lizard (Varanus giganteus), the top order carnivore in that landscape.

They’re quite a formidable beast. If you come across a perentie in the landscape, you want to look for a tree, I think. They can grow up to over six feet in length so they’re quite big, formidable creatures.

I made several field trips with Billy to the south-west corner of the territory where he collected timber for his carvings or I remember him collecting a flitch of wood from a mulga to make a miru, or a spear thrower.

It was wonderful seeing him working at it next to the fire. He was just a consummate craftsman. It was beautiful.

I worked with a number of senior Aboriginal men at Uluru burning — patch burning — the landscape.

We tried to reintroduce the traditional burning practice, breaking up the country into patches so that wild fire wouldn’t sweep through and destroy the landscape. There’d always be different patches in different stages of recovery, which meant a lot in terms of habitat requirements for particular species, food species in particular.

I worked with people like Norman Tjakalyiri Ngurjakaliri and Katakura Katacura who were very senior men and were artists in their use of fire. They really knew to how to burn in a very controlled sense.

Burning was not only important in breaking up the country in our context trying to prevent wild fire but also in the sense of propagating a range of edible species, plant species in particular.

For example, if a spinifex plain was burnt, a particular plant that would respond really well was desert raisin or kampurarpa, (Solanum centrale), a very sweet fruit — bush tomato some people call it.

But it also as a plant attracted a kiparaor, a bush turkey (Ardeotis australis), the bustard, which also has very good eating. So you could see a cycle. You burnt to produce food which would attract food in the landscape.

It also produced a number of grass species that were used to produce flour for a form of bread, a grass called wananung wangunu in Pitjantjara, or woolly butt (Eragrostis eriopoda) in our vernacular. That was readily collected by the women and yandied or winnowed and threshed and turned into flour.

So fire was very important in producing an array of food in the landscape.

If we’re talking about fire in the landscape, it’s important to really realise that we need an array of vegetation communities of different age. In other words, we talk about old growth forests even in the Centre. In the desert we need old growth mulga communities or even old growth spinifex communities for different species.

Different species require different vegetation communities of different age structures. For example, the mallee fowl, or nganamara (Leipoa ocellata) as it was locally called, required unburnt patches of mallee over 40 years old. They were very important in the landscape.

If wild fires were to consume extensive areas of mallee destroying the old growth, we’d lose the habitat for the mallee fowl. In fact, while I was the ecologist at Uluru, Joe Benshemesh, a scientist from Victoria, rediscovered a mallee fowl population in the north-west corner of South Australia. I managed to take a number of senior men down to visit this discovery.

And Norman Tjakalyiri in particular who was very excited to be able to actually hold a mallee fowl egg, a ngampuin, in his hand and talk about how he used to eat these as a boy. So that was a very significant rediscovery of a species requiring a particular plant community of a particular age structure in the context of fire in the landscape.

Mulga communities are really important in an economic sense for local people. Mulga is the source of some of the best timber for cooking, some of the best timber for making digging sticks, a variety of artefacts.

But in a food sense, it’s the source of honey ants. Honey ant chambers would be located beneath mulga trees, and the women would spend hours digging out to almost a metre in depth, or greater, to get to the chambers of these honey ants.

They’d sweep out the honey ants using a little stick or they could use a spinifex leaf or a twig of mulga just to sweep the honey ants out into a piti; or a coolamon, a bowl, and collect them for eating.

The witchetty grub, or makuas the locals call it, has a very specific relationship with the particular plant species Acacia kempeana, or ilykuwara as it’s called in Pitjantjara. The grub itself lives within the roots of the ilykuwara. So the women would dig the roots out, extract the maku, and either eat it raw or it was very nice lightly roasted on hot coals. It tasted a bit like scrambled eggs on hot coals — very nice.

Tjilkamata Tjilkamataor — the echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) — or the locals actually called it porcupine, was a highly prized item of food. Fatty deposits were highly sought after as a food.

Recorded at the National Museum of Australia in 2013

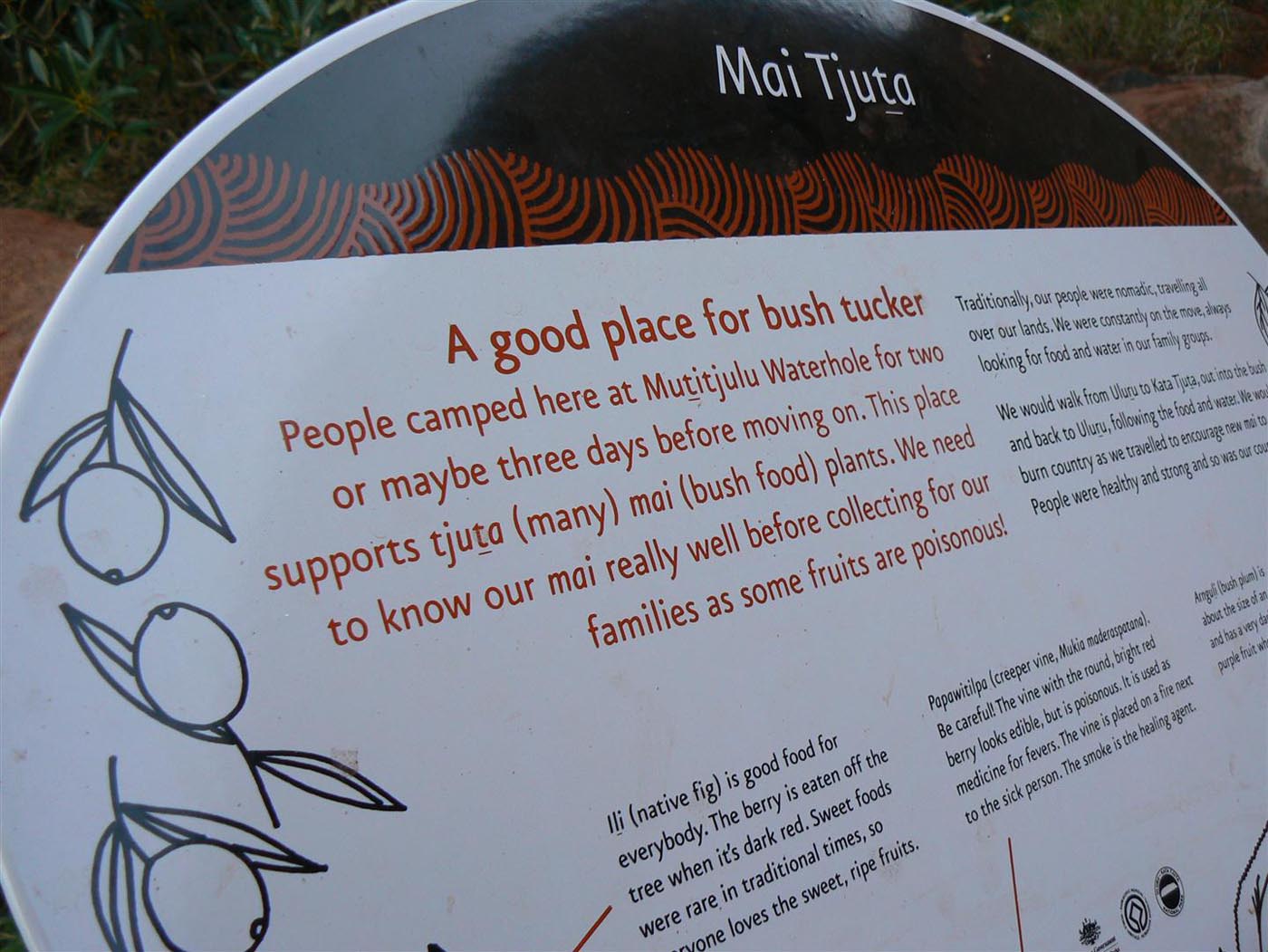

Tourism and tucker

Tourists dine at Yulara restaurants and cafes each evening, and on daytrips into Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park they encounter a variety of edible animals and plants. Guides and interpretive signs identify a number of these local ‘bush food’ species, and explain their significance.

Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara traditions of storytelling and art production consistently honour and celebrate the many desert species on which they have long relied for nourishment.

To learn more about the bush tucker of the Uluru region, visit Parks Australia.

Uluru souvenirs

The significance of Uluru as a tourist destination is reflected in the National Museum’s collection, which holds a range of souvenirs bought by tourists visiting the iconic destination.

Perhaps because of the isolation and aridity of the national park, some of the souvenirs celebrate the surprising diversity of bush foods that grow in the surrounding desert.

Yulara School

Yulara School is located about 340 kilometres southwest of Alice Springs, in the isolated tourist village of Yulara. The school is part of the Lasseter Group School and provides education services to students from preschool to middle years. Yulara School largely caters for children of families working in Yulara hotels and in other businesses that serve tourists.

References

Diana James, Desart: Aboriginal Art and Craft Centres of Central Australia, Desart, Alice Springs, 1993, p. 25.

Diana James and Elizabeth Tregenza, Ngintaka, Wakefield Press, Adelaide, 2014, p. 166.

Explore more on Places and objects