Downer, Watson and Dickson are northern Canberra suburbs on the lower slopes of Mount Majura, in the Australian Capital Territory. Before the construction of the suburbs in the 1960s, much of the land was an agricultural experiment station operated by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

Scientists at the station generated ideas to boost the productivity of modern farmland. Australian and international farmers regularly visited the station to discover the findings of cropping and grazing trials. Playing fields, houses, wide backyards, and many bountiful vegetable gardens now cover the station site.

Stump-jump plough

In 1980 the CSIRO donated to the National Museum a stump-jump plough used to groom the paddocks and trial plots of the Dickson Experiment Station, where the houses and gardens of Downer and parts of Dickson and Watson now stand.

An Australian invention

The plough used by the CSIRO's Division of Plant Industry is an eight-furrow, mouldboard, stump-jump plough. Stump-jump ploughs are an Australian invention developed in the 1870s by brothers and South Australian farmers Richard and Clarence Smith.

In the Australian colonies, the 1870s was a period of land reform, closer rural settlement, railway expansion and commercial development.

Farmers sought new technologies and methods to swiftly transform diverse biological communities, often dominated by eucalyptus trees, into simplified monocultures of imported crop species.

They hastily cleared scrubland, burnt what timber they could, then used horses to drag stump-jump ploughs through their new, ashen paddocks, strewn with stumps, roots, and the many stones that characterise the old, shallow soils of Australia.

The new plough’s great innovation was a linkage mechanism that allowed each individual ploughshare to lift over roots, stumps, and rocks, thereby avoiding damage to horses and equipment.

Dickson Experiment Station

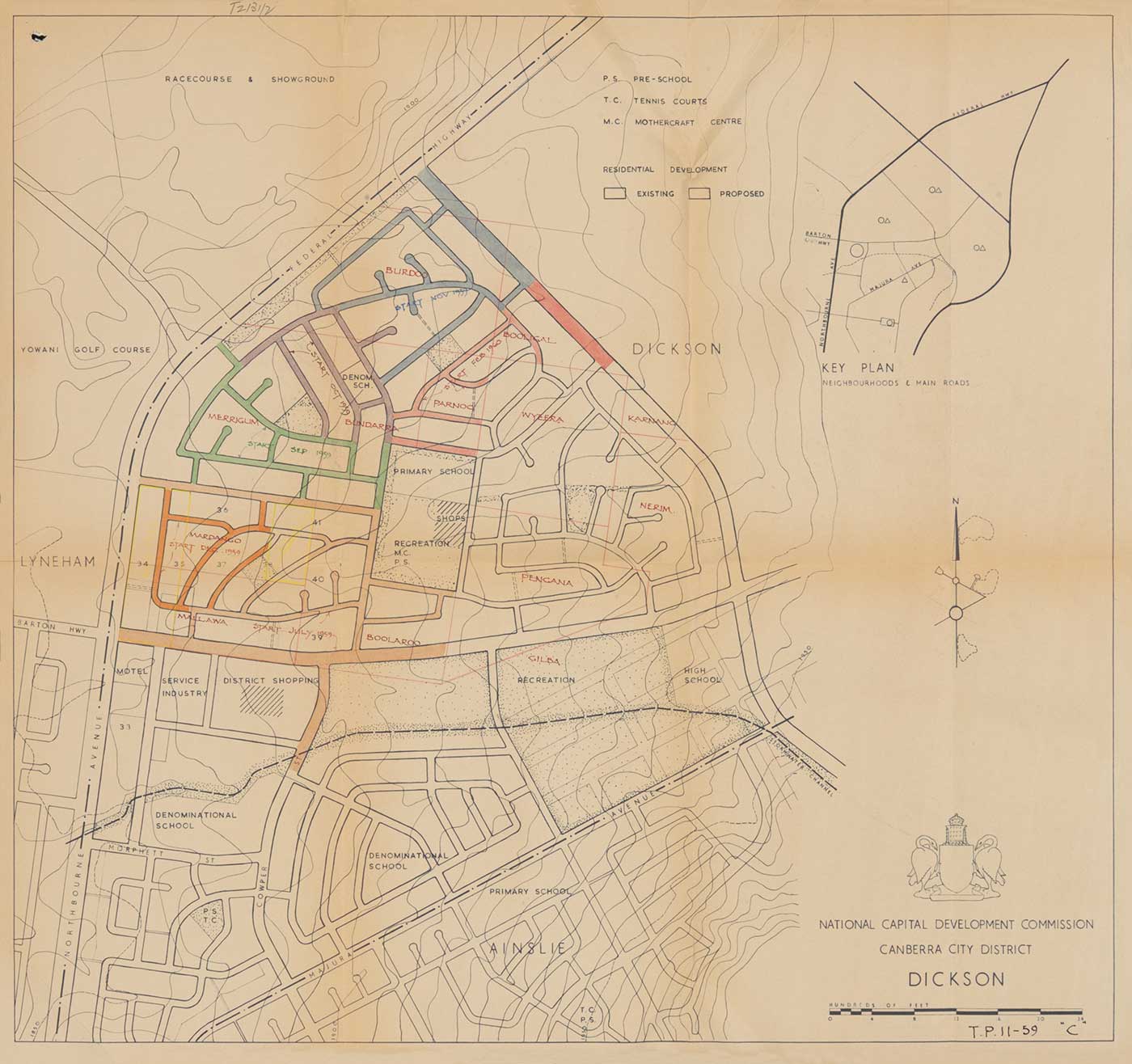

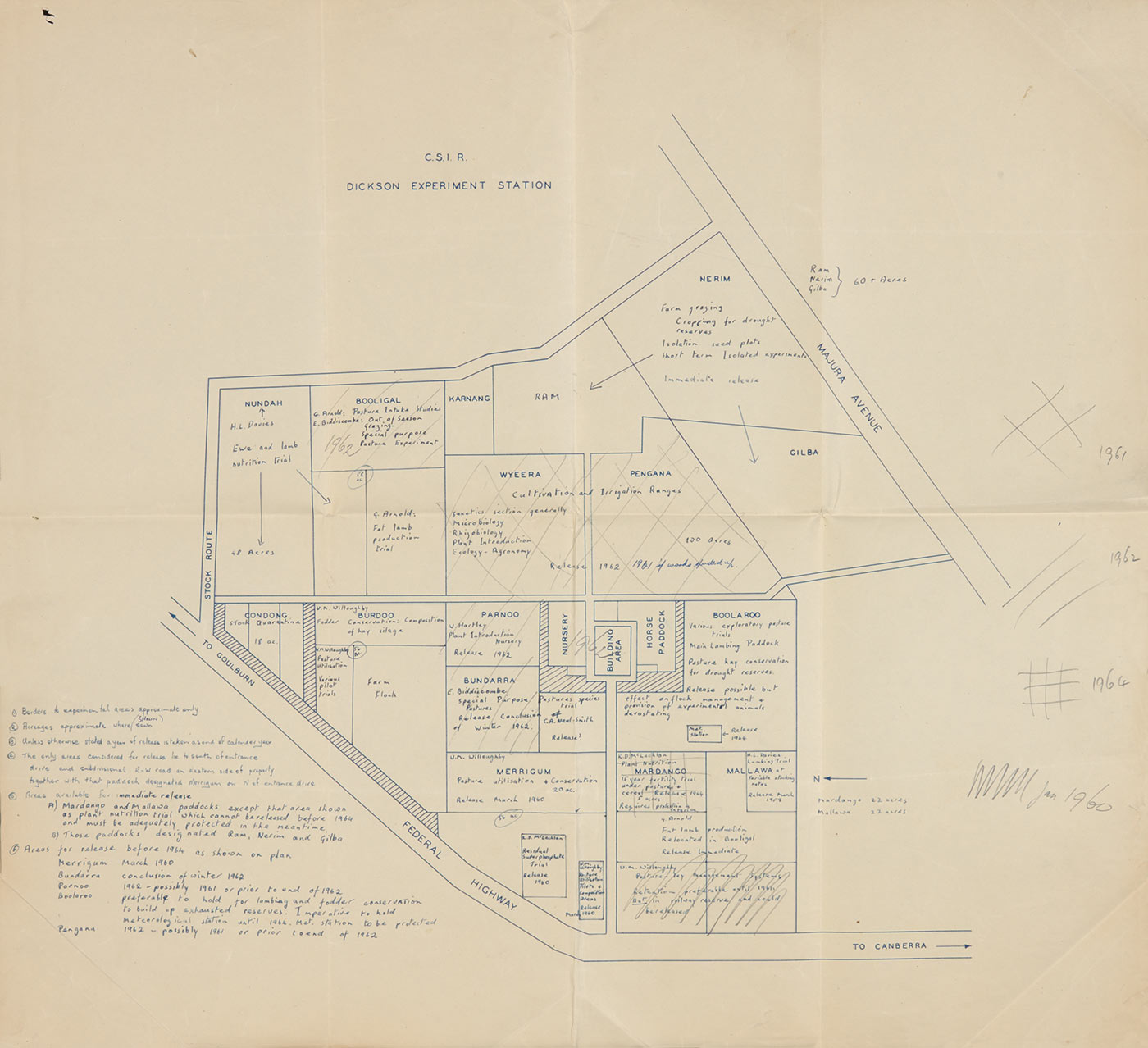

Between 1940 and 1962 the CSIRO operated the Dickson Experiment Station, then on the northern edge of Canberra. Experiments aimed to breed more productive crop and pasture strains, and to discover ways that land could sustain more livestock.

Scientists ran a large flock of merino and Border Leicester sheep, established pastures of clover, lucerne, wimmera grass and rye grass, and grew crops of grapes, peas, tomatoes, beans, potatoes, cabbages, onions, wheat and oats.

To communicate their scientific findings, CSIRO ran field days at the station, with lunches prepared and served by the local branch of the Country Women’s Association. For two decades, farmers from across Australia and around the world encountered new ideas about food production at the Dickson Experiment Station.

As the national capital grew, government planners demanded access to the wide paddocks of Dickson Experiment Station for suburban development. The CSIRO decided to close Dickson Experiment Station, and in the early 1960s it established a new research station at Ginninderra, further west.

Robert Campbell and the Majura cattle run

Robert Campbell was a merchant based in India before he migrated to Sydney in 1798. In Sydney, Governor King engaged Campbell to import horses and more than 2000 head of cattle from India.

Campbell received one of the first land grants in the Canberra area. In the 1820s and 1830s his family established a sprawling grazing property across grasslands long tended by the local Ngambri and Ngunnawal people.

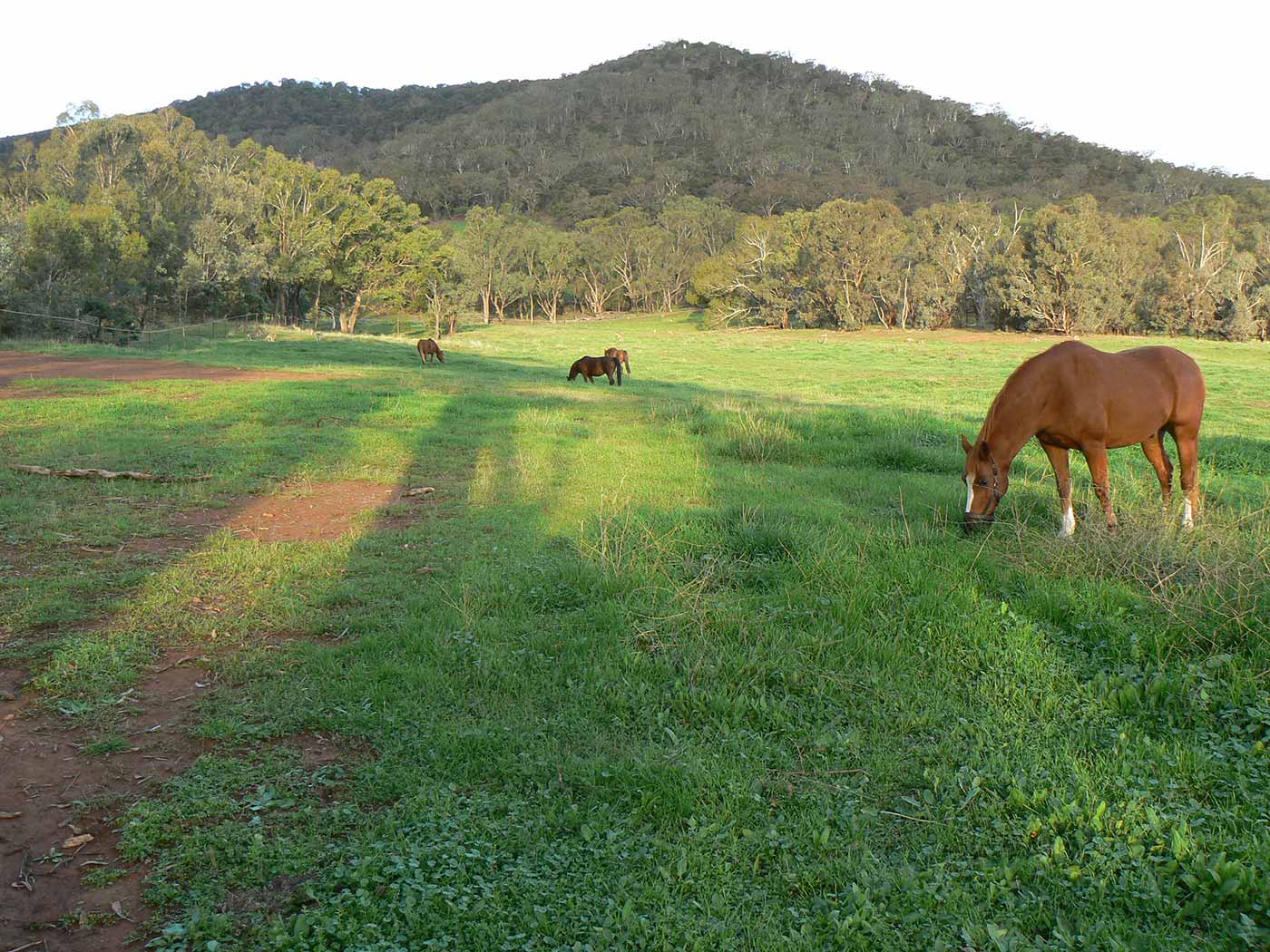

Campbell named his cattle station ‘Majura’, possibly to honour an Indian locality of the same name. Settlers called the great hill bordering the western side of Campbell’s cattle run Mount Majura.

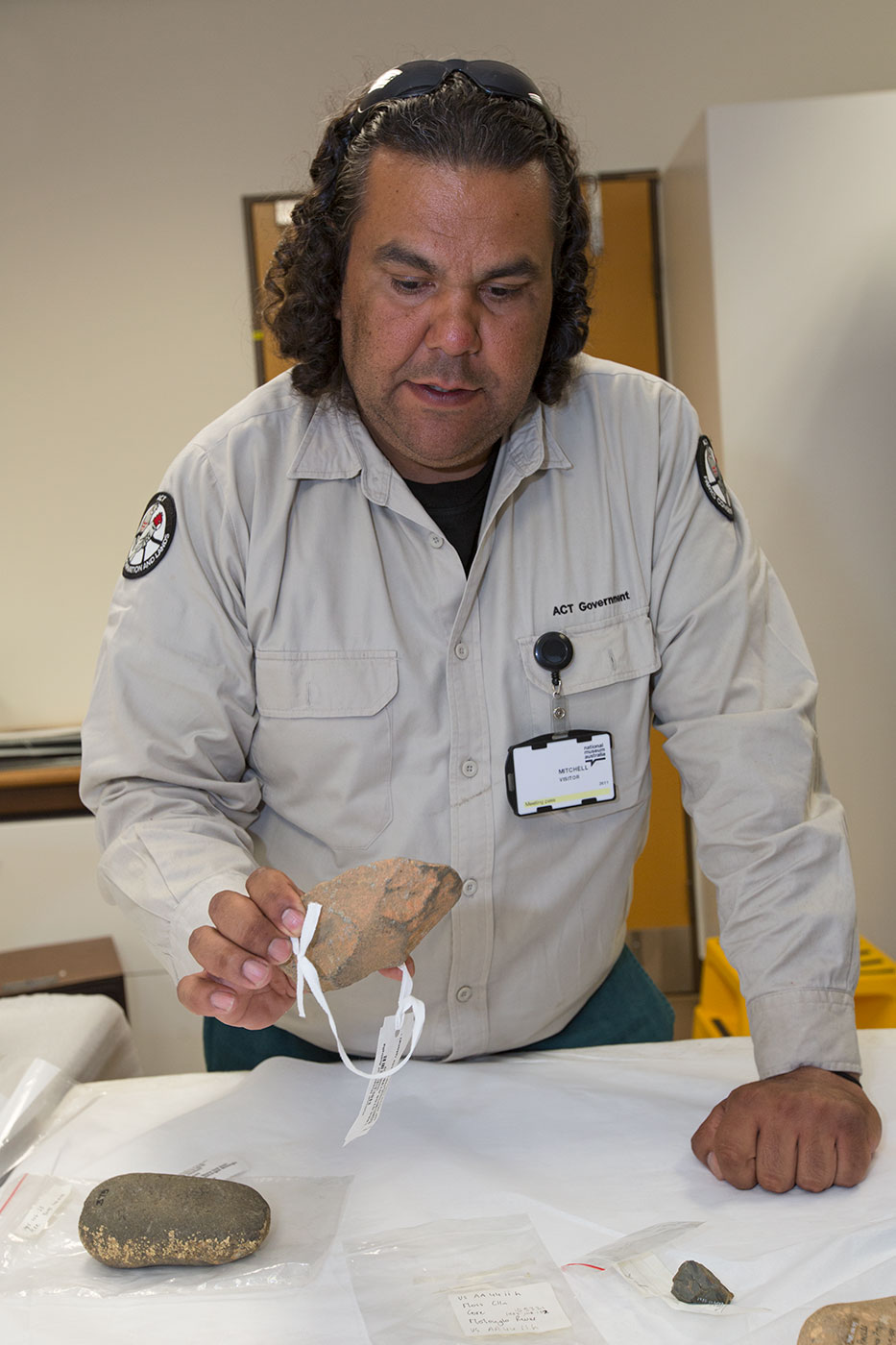

Indigenous history

In 1826 Ngunnawal and Ngambri warriors probably walked to Weereewa (Lake George), north of Majura, to join a regional uprising of 1000 Aborigines angry about pastoral colonisation and its destructive effects on Aboriginal land and society.

Governor Darling decided to send a detachment of troops ‘to enforce obedience and disperse them’.

An article later published in the Sydney Gazette explained that order was returned after a fearful threat made by Captain Bishop of the 40th Regiment of Foot to an Aboriginal leader:

By means of an interpreter, Captain Bishop made him acquainted with His Excellency’s instructions in reference to the determination of the Government to afford the aborigines every protection and encouragement, in the event of their allowing the stock-keepers, and other defenceless Europeans, to remain in safety; while, on the other hand, this sable chieftain was given to understand, that the troops would be despatched in pursuit, with orders to destroy every native, should the stockmen, or any other unoffending European, be molested after that interview. The chief was much alarmed, and promised the most implicit obedience to all that the Captain had to advance; and, after some delay, the captive was restored to liberty, when he was not long ere he rejoined his sable companions, and doubtless gave them all the requisite information, as they were not to be seen afterwards.

West of Majura, on Charnwood station, pastoralist Henry Hall found Onyong, a leader of the Ngambri, spearing cattle, and shot him in the leg. In 1831, Robert Campbell presented Onyong with an inscribed brass breastplate that acknowledged his seniority and leadership.

Early pastoralists often gave breastplates to Aboriginal leaders during negotiations to secure cooperation with local clans, and grazing rights to their land. William Wright grew up on Lanyon station, on the Murrumbidgee River south of Majura in the 1840s and 1850s. He remembered Aboriginal men as ‘splendid stockmen’ and good friends:

Neddy and Long Jimmy were tribesmen, and our stockmen. And very good and careful stockmen aboriginals usually were. The two I mention were great cobbers.

Wright admired the rough-riding talents, and characters, of his Aboriginal workers:

The best rider of buckjumpers I ever knew was a native named Frank. He was a drover in my employ for many years, and both as drover and horse-breaker he was in a class by himself. One native named Duke was with me droving to Queensland on one occasion, and proved a trustworthy man, one of the cleverest assistants I ever had. He was usually employed by me at dairying or general work among stock and in the paddocks.

Robert Campbell built huts on the Majura cattle run, on the eastern side of Mount Majura, for his workers and their families. Many had recently migrated from Scotland and England on ships owned by Campbell.

English migrant Alfred Mayo worked for Robert Campbell, as did his son William, who lived at Majura.

William, his wife Mary and their 10 children stayed at Majura after the Commonwealth government bought the cattle station in 1913. The Mayo family ran 40 dairy cows.

As an elderly woman, William and Mary’s daughter Ethel remembered fondly her home at Majura, and her mother’s delicious cooking:

The camp oven and big kettles and cauldrons hung on hooks from a great iron bar over the flames, and the cakes from that oven were as good as anything you get these days — light as a feather.

The bushland of Mount Majura nourished cattle in dry times. Isaac Blundell remembered his father cutting the branches of drooping she-oaks to save his cattle during the intense drought of 1858.

Ngunnawal and Ngambri people watched the climbing plant Hardenbergia violacea closely. The appearance of its bright purple flowers indicated that certain fish species in the nearby Molonglo and Murrumbidgee rivers had grown fat, and were ready for eating.

Samuel Shumack, whose father worked for the Campbell family as a station hand, once spoke to an ‘old hand’ who recalled Aboriginal methods of fishing on the Molonglo:

There was a long waterhole in the Molonglo River near the Duntroon dairy, and about a dozen stalwarts would enter the water at one end. A few minutes later most of the tribe would enter the waterhole at the other end and move forward, making all the noise possible. This disturbance drove the fish to the other end, where the natives speared a great many.

Majura Primary School

Majura Primary School is situated in the north Canberra suburb of Watson, and is the local neighbourhood school for children from Watson and the nearby suburb of Downer. Majura joined the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Foundation program in 2010 and is the foundation’s demonstration school for the ACT and the surrounding region.

References

‘CSIRO Field Day at Dickson’, Canberra Times, 1 October 1952.

‘Dickson Experiment Station’, typescript and handwritten notes, no date, CSIRO Archives.

‘Discovery of Lake George’, Queanbeyan Age, 21 March 1919, p. 2.

‘Finding Garrett Cotter’, Canberra Times, 11 October 2013.

Greening Australia Capital Region, Koori Bush Tucker Garden, Greening Australia, Canberra, 2013, p. 8.

Historical Records of Australia, Series 1, Vol. XII, pp. 269–270.

Charles ET Newman, The Spirit of Wharf House: Campbell Enterprise from Calcutta to Canberra, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1961, pp. 201–202.

‘Pioneer Relives Monaro’s Horse and Buggy Days’, Canberra Times, 12 August 1964, p. 17.

Samuel Shumack, Tales and Legends of Canberra Pioneers, Australian National University Press, Canberra, 1967, p. 151.

Sydney Gazette, 7 June 1826, p. 2.

Margaret Steven, ‘Campbell, Robert (1769–1846)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published in hardcopy 1966, accessed online 10 April 2014; ‘The Late Mr. Campbell’, Sydney Morning Herald, 27 April 1846, p. 2.

William Davis Wright, Canberra, John Andrew & Co, Sydney, 1923, p. 15, 62 and 66.