The designer

Sharon Peoples, who designed the Crimson Thread of Kinship, is a textile artist specialising in embroidery. A member of the ACT Embroiderers' Guild since 1986, Sharon has worked with guild members on a number of large embroidery artworks.

'I enjoy not only the colour and tactility but also the meditative qualities of sitting and embroidering. I feel a deep connection with the women who have worked in this medium for centuries,' Sharon explains.

Sharon's art explores the social construction of gender, particularly within domestic spaces, and ideas about utopian societies.

She sees collaborative embroidery projects as both an artistic practice and a means for building communities.

Sharon Peoples

For me as a designer, [embroidery is] increasingly a metaphor for story telling. The crimson thread symbolises the creation of Australian history and invites us to embroider our own story for the future.

The embroiderers

The ACT Embroiderers’ Guild was formed in the Australian Capital Territory in 1962 to offer advice on design and technique to Canberra’s embroiderers.

It now includes over 200 members who meet to share ideas and skills and to stitch with friends. Guild members create individual pieces and collaborate on major commemorative works.

In 1999, the guild secured a grant from the National Council for the Centenary of Federation to make an embroidery for the National Museum of Australia.

Sharon Peoples was commissioned to design the work and members began stitching in January 2000.

June Mickleburgh, embroiderer

We worked between 8.30am and 3.00pm on Monday evenings and on weekends. Six women worked together at a time, three on either side of the frame. Everybody did at least 10 hours. We had a roster and six experienced members shared the supervision ... Film reviews, books we’d read, gossip, meeting other members — it was great fun!

Conservation considerations

National Museum conservators Robin Tait, Anne I'Ons, Carmela Mollica and Judith Andrewartha worked with the guild embroiderers and designer Sharon Peoples to create the Crimson Thread of Kinship.

The conservators assisted with selecting materials for the embroidery, washing and preparing the linen and, when stitching was complete, mounting each panel onto a handcrafted wooden frame.

The conservation process ensured that the embroidery will be preserved for future generations to enjoy.

The speech that inspired the title

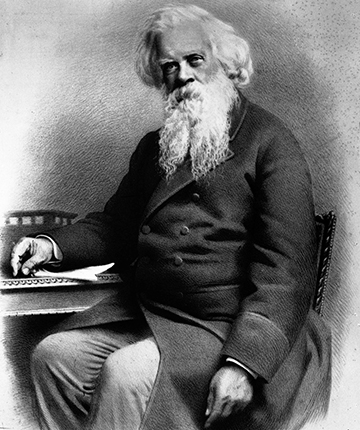

During the 1890s Sir Henry Parkes emerged as a leader of the Federation movement dedicated to forming the Australian colonies into a single Commonwealth.

The first of several conferences to discuss a new Australian Constitution was held in Melbourne in February 1890.

At the conference banquet, Parkes, then premier of New South Wales, declared that disagreements among the colonies over trade protection policies should not prevent Federation.

He argued that Australians were members of a single colonial family, united by ‘the crimson thread of kinship’. The phrase became an enduring catchcry of the Federation movement.

Embroidery in Australia

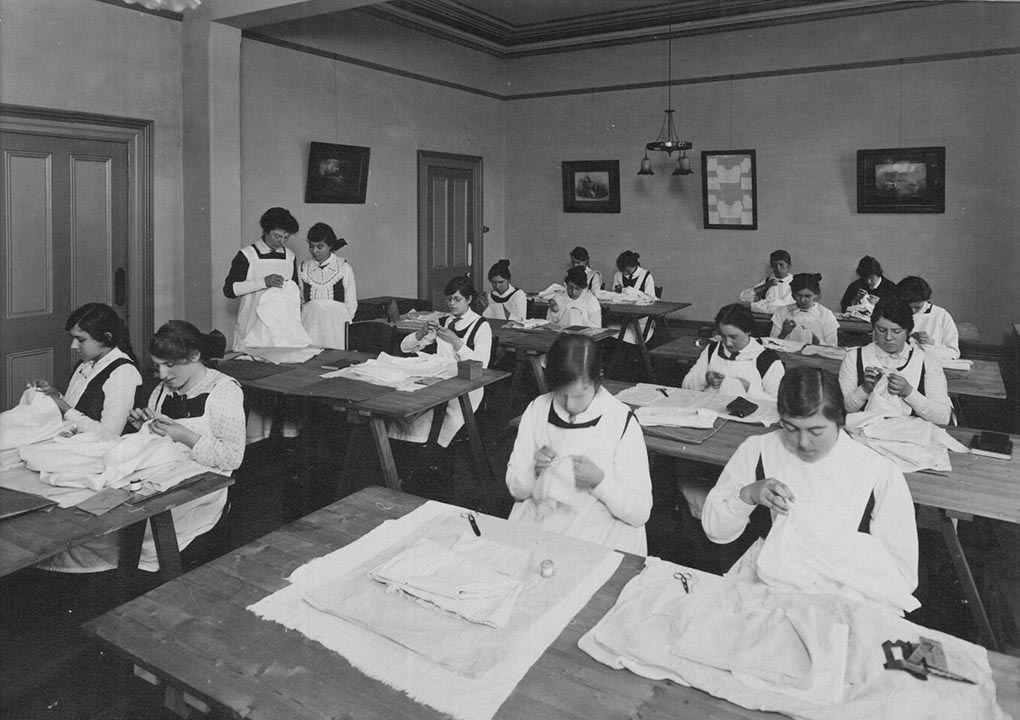

Needlework has always been a part of life in Australia. Like Indigenous Australians, European settlers sewed to make and mend clothing and other textile objects. More affluent women also created decorative embroidery, or ‘fancywork’, to embellish the home and church and occupy idle hours.

In the 19th century, needlework was seen as essential to a girl’s education and embroidery designs often carried religious and moral messages or depicted national symbols.

During the 20th century, women increasingly used embroidery to commemorate significant family and community events. The Country Women’s Association and embroiderers’ guilds around Australia facilitated collaborative projects and encouraged creative individual work. In the 1980s, for example, each state guild contributed to a 16-metre embroidery for the new federal Parliament House in Canberra.

Needlework has become less important as an everyday skill but embroidery continues to be a means of creative expression and a way to record significant events. Embroiderers sustain a tradition of meeting to talk, tell stories and ‘paint with a needle’.

Explore more on the Crimson Thread