It is not known when or why gorgets were first given to Aboriginal people. The oldest known Aboriginal gorget is dated 1815 and by the 1820s presentation of gorgets to Aboriginal people was a well-established practice.

Most of the gorgets were very similar to military gorgets in their deep crescent shape and formal decorations. However, Aboriginal gorgets were usually at least twice the size of military gorgets. The oldest examples are usually the smallest.

The presentation of inscribed plaques after the style of gorgets may have been a development from an earlier practice that was part of the strategy used by European colonisers.

The use of commemorative medals or tokens by English and other European explorers as gifts for the inhabitants of newly ‘discovered’ territories was well established by the late 18th century.

For example, James Cook gave bronze medals on long ribbons to the Aboriginal people he met at Adventure Bay, Tasmania in 1777.

Two thousand medals commemorating Cook’s second voyage had been struck by the Navy Board, in 1772, as gifts for people he would meet during his voyages.

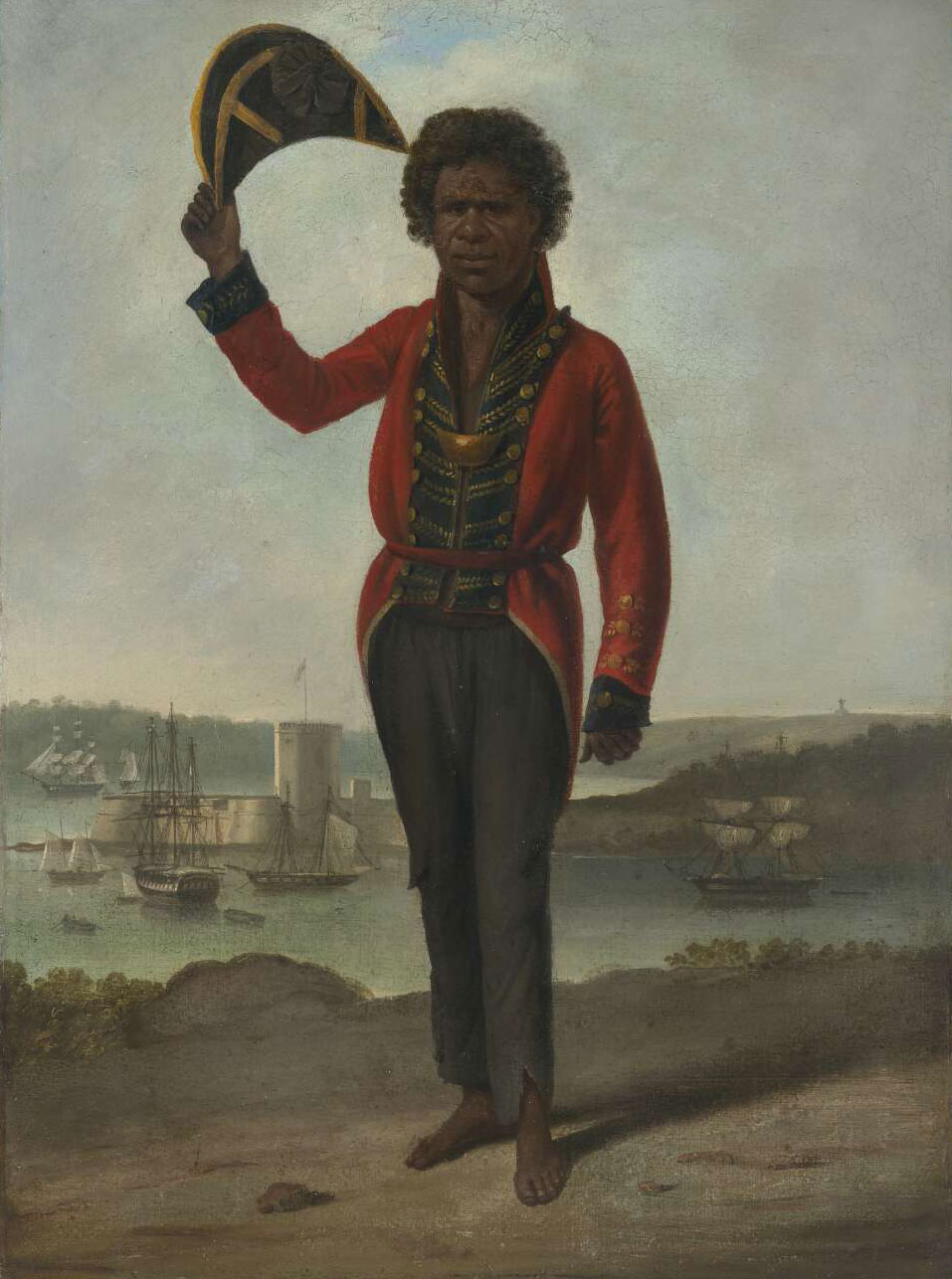

King Bungaree

[1] Medals continued to be presented to Aboriginal people throughout the 19th century and well into the 20th century.

Faddei Bellingshausen, observer for the Russian government and captain of the Russian navy’s exploring sloop Vostok, which was in Sydney in 1820, presented King Bungaree with a bronze medal in addition to a hussar’s greatcoat, and a white blanket and pair of earrings for his wife.

[2] In 1911 an Aboriginal man of Roper River was given a medal for valour inscribed, ‘Presented in the name of His Majesty to ‘Neighbour’ an Aboriginal native of the Roper River for gallantry in saving life on the 1st Feb., 1911’. [3] In 1912 Mogil, an Aboriginal man of the Barwon River people, was presented with a ‘handsome gold medal’ when he retired from service as a tracker with the Orange police. [4]

Gifts from colonisers

Gorgets were used as gifts to Indian leaders and warriors in North America by both French and British colonisers. The English presented silver gorgets like those worn by their troops to Indian warriors of the six Iroquois nations which supported England in the Seven Years War, 1755–62, against the French.

The French also had Indian troops and ‘medal chiefs’. Indians wore numbers of the silver gorgets, as many as 12 at a time, each hanging below the other on their chests. [5]

The use of gorgets as gifts to the Indians of North America would have been a practice well known to the marines who were sent to Australia.

The first gorget presented in Australia could have been a gorget which belonged to a marine officer who gave it, or a copy with a new inscription, to an Aboriginal friend who admired the decoration. It is clear that the gift of a gorget was considered by the colonists and at least some Aboriginal people to be an honour.

An Aboriginal person wearing a gorget was, certainly from the colonists’ point of view, considered to be a leader within the Aboriginal community.

Symbols of authority and importance

As military duty signs worn only by officers, gorgets had public recognition as symbols of authority and importance. Therefore, when the colonists were looking for a way in which to honour individual Aboriginal people, the gorget was a logical model.

Gorgets could be inscribed with the wearer’s name and an honorary title such as ‘King’ or ‘Queen’ and they were durable and easily worn around the neck on a chain or cord.

By the 1830s it was common practice among pastoralists to present the Aboriginal man perceived to be the local leader with a gorget stating his position of authority in the vicinity of the settler’s new property. In return, the Aboriginal leader was expected to prevent his people from interrupting the settler’s pastoral endeavours and where possible to supply labour or information about the land.

Gorgets were also given to Aboriginal people as tokens of gratitude for acting as guides to exploring parties, for helping in the establishment of pastoral properties, for their contribution as police or trackers, for saving people’s lives or simply for being the ‘last’ living member of a ‘tribe’.

Oldest known gorget in Australia

The oldest known gorget, dated 1815, belonged to King Bungaree who was a famous Sydney identity. Both he and his wife Queen Gooseberry had gorgets made for them by Governor Lachlan Macquarie.

Bungaree’s may have been the first Aboriginal gorget and the idea, therefore, attributable to Governor Macquarie. Macquarie had experience in the Americas and may have become familiar with the practice of presenting gorgets to Indians during that time.

[6] Macquarie made many more presentations of gorgets in an attempt to ingratiate himself and his government with the Aboriginal people who he believed had power over the general community. He began in December 1816 by presenting gorgets to all the Aboriginal leaders who attended the first of what were to be annual gatherings of the Aboriginal population at Parramatta.

Good relations

Macquarie planned to hold an annual feast to maintain good relations between the colonial administration and the Aboriginal communities. He was intent on ‘civilising’ the Aboriginal people of New South Wales and in order to do so he needed help from the Aboriginal people respected by the general community.

In order to obtain the help of such people he needed to affirm their positions in the eyes of both the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities. Macquarie wrote in his diary (1 January 1818) about the presentations he made at the ‘Native conference’:

I presented Gorgets to Cogie as Chief of the George’s River Tribe, and to Norwong as Chief of the Botany Tribe and the Order of Merit to Tindall of the Cow Pastures and Pulpin of the Hawkesbury Tribe. [7]

The feasts continued until January 1830 and even when they ceased Aboriginal people continued to gather at the Field of Mars where the last feasts were held. All Aboriginal people were invited to the feasts and many came a very long distance to attend.

The governor conferred with the appointed representatives of the groups during the feast, and as a symbol of their authority and status he gave each one of them a brass breast-plate or gorget. They were also given to other natives for their loyal services to the military and government officers. He thus initiated a custom among the white people that spread all over Australia; they found in these breast-plates a convenient way of recognizing the loyalty and faithful services, or of establishing the position of whoever appeared to them to be the highest in rank, of natives on cattle and sheep stations, government reserves, and mission stations. [8]

Following Macquarie’s example, gorgets became very popular with colonists as gifts for Aboriginal people. In 1822 the famous explorer William Lawson suggested to Governor Brisbane that brass plates should be presented to the chiefs of five tribes in the area around Bathurst.

[9] His suggestion was followed and three gorgets which have been located in a private collection may well have been of those five. They are inscribed ‘Thommy Weavers, King of Curvy, Kangaroo Swamp’, ‘King Wagor-Day, Black Rock, Bathurst’ and ‘Jacob, King of Bathurst’.

Heroic actions and general fame

By the mid-19th century hundreds of Aboriginal people had been presented with a gorget by colonists grateful for services rendered or in expectation of future services. Heroic actions and general fame were also rewarded with the gift of a gorget. The government continued the practice by distinguishing its Aboriginal policemen and trackers with gorgets:

The gift of a brass medal, formerly a rare distinction, is now made so frequently by settlers to natives who have served them well in any way, that the honour of the badge is somewhat diminished; but the pride with which the possessor wears and displays the insignia of his order is most amusing. The ‘medal’ consists of a piece of brass in the form of a crescent, not much less than a cheese-plate, engraven with the name and style of both owner and donor, and worn hung round the neck by a brass chain. [10]

The practice was well established that when, in 1836, Captain William Lonsdale took up his position of Police Magistrate for the colony of Port Phillip (now Victoria) he took a consignment of gorgets as presents for local Aboriginal people. Part of Lonsdale’s commission was to improve relations between Aboriginal people and colonists.

Gifts such as food and clothing ‘were ordered to be distributed in return for their friendly behaviour, for work around the Government Mission, and sometimes to relieve cases of dire need’. [11] Among the gifts Lonsdale was issued with from the government stores were ‘twenty five brass plates and chains ... presented to the black natives’. [12] Gorgets had evidently become, at least in the eyes of the colonial administration, an important element in the ‘civilisation’ of Aboriginal people.

Footnotes

[1] DJ Mulvaney, Encounters in Place: Outsiders and Aboriginal Australians 1606-1985, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, 1989, pp 33-35.

[2] Kiselyov, 1820 in G Barratt, The Russians at Port Jackson: 1814-1822, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1981, p. 32.

[3] National Library of Australia Pictorial Collection, Australian Aborigines.

[4] Anon, ‘Mogil - A Western District Black Trader’, Presentation to Mogil, Australian Town and Country Journal, November 1912.

[5] K Vincent Smith, King Bungaree: a Sydney Aborigine Meets the Great South Pacific Explorers, 1799-1830, Kangaroo Press, Kenthurst, 1992, pp 81-82.

[6] Vincent Smith, p. 81.

[7] Macquarie quoted in Vincent Smith, p. 82.

[8] FD McCarthy, ‘Breast-plates: the Blackfellows’ Reward’, The Australian Museum Magazine, 1952, vol. 10, p. 327.

[9] J Jervis, ‘William Lawson, Explorer and Pioneer’, Journal of the Royal Australian Historical Society, 1954, vol. 40, no. 2, p. 88.

[10] LA Meredith, Notes and Sketches of New South Wales During a Residence in that Colony from 1839 to 1844, John Murray, London, 1844, p. 100.

[11] M Cannon (ed.), Historical Records of Victoria, Volume 2A: The Aborigines of Port Phillip 1835-1839, Victorian Government Printing Office, Melbourne, 1982, p. 191.

[12] Colonial Secretary, The Colonial Secretary to William Lonsdale, 13 September 1836 and 24 September 1836 in Cannon, M (ed.), Historical Records of Victoria, Volume 2A: The Aborigines of Port Phillip 1835-39, Victorian Government Printing Office, Melbourne, 1982, p. 192.