Collector of gorgets

The tradition of collecting artefacts made by or associated with Aboriginal people became well established during the first years of British colonisation of Australia. In the first months of settlement, in 1788, the First Fleet of colonisers did a roaring trade in artefacts with the visiting French expedition, led by La Perouse.

Many of the artefacts were stolen and the trade became one of the earliest sources of friction between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Australia. In the 19th century collections of Aboriginal interest became very popular with Australian philanthropists, and many people with the time and money built special rooms to house their curiosities.

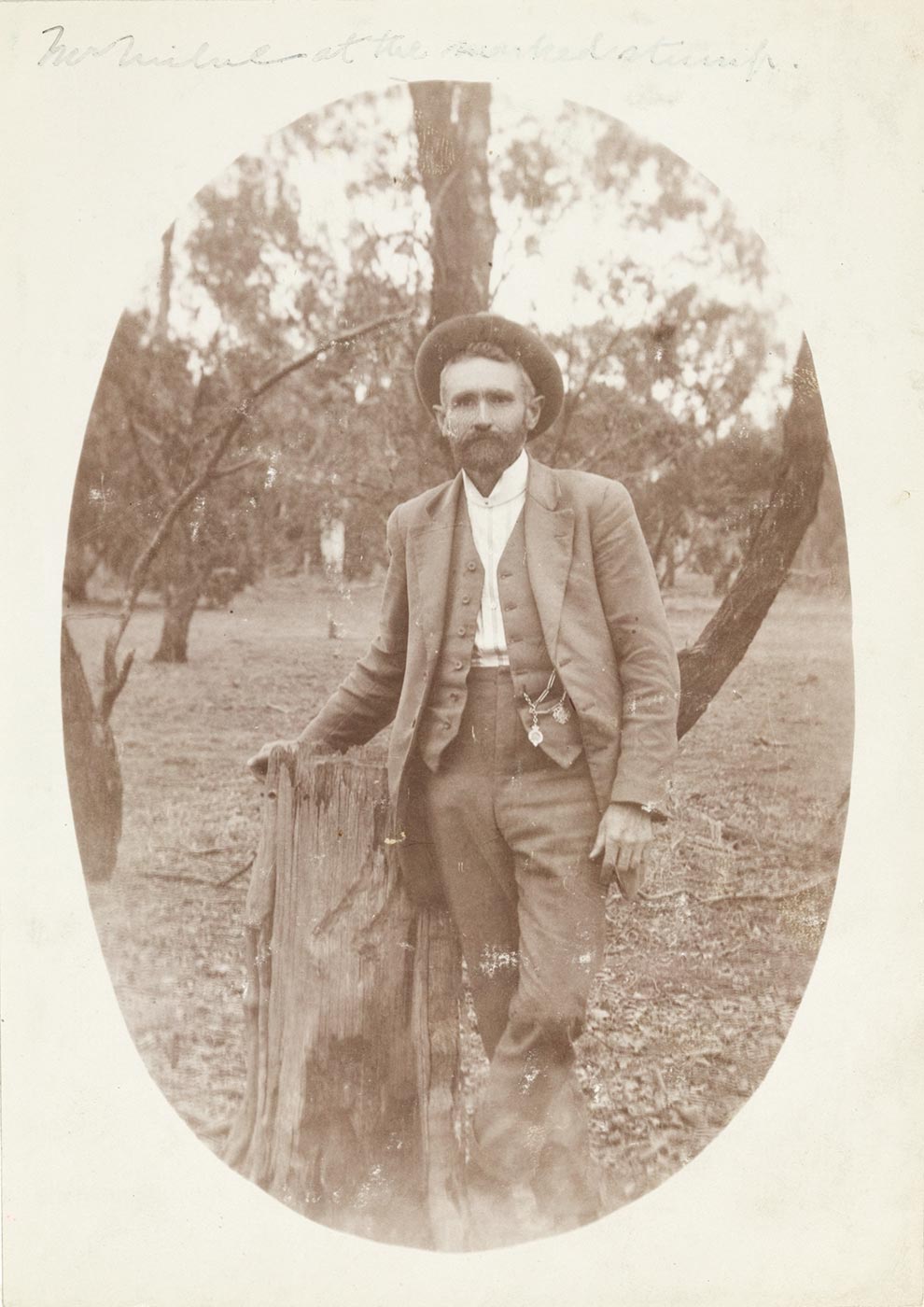

One such philanthropist was the amateur ethnographer Edmund O Milne.

Twenty-four of the 33 gorgets held by the National Museum of Australia were collected by Milne in the late 19th to early 20th century. In his capacity as a railways inspector, Milne travelled throughout New South Wales and made many connections further afield.

In his travels and using his networks he was able to acquire artefacts of Aboriginal interest and to document some of the history of those artefacts. He kept scrapbooks and albums of photographs to supplement his collections.

What started as a childhood hobby for Milne became an all-consuming passion and in his lifetime he amassed a huge private collection of Aboriginal artefacts. [1] Fortunately he considered Aboriginal gorgets to be of ethnographic interest and sought them out wherever possible.

Milne followed many leads in his attempts to obtain gorgets for his collection and from his correspondence it can be construed that his interest was becoming widely known. For example, John Jones who wrote to Milne, on 20 March 1912, in answer to his query about a plate already in his collection, closed his letter with information about another lead:

Should you want another plate I heard at Cobbora that a man, William Miller had found a plate at Mundooran inscribed with the name of the King and presented by G.M. Rouse. If you write to B.C. Cox, Kilwinning, Cobbora, he will give you further particulars, as I asked him to see Miller, and tell him not to part with the plate until he heard from you. [2]

Milne built a room onto his house in Sydney to house his ethnographic collection. In an attempt to safeguard the collection for posterity and to ensure the perpetuation of his own name, Milne willed his entire collection to the Commonwealth of Australia to be deposited in the first ‘Federal Museum’:

I give devise and bequeath unto my said Trustees my Anthropological collection upon trust for my son Edmund Osborne Milne for his sole and separate use and benefit absolutely provided however and I hereby direct that it shall be presented to the first Federal Museum opened in the Federal Capital under the name of ‘The Milne Collection’. [3]

The Australian Institute of Anatomy solicited for the collection, claiming to be the benefactors under the terms of Milne’s will. In 1931 their bid was successful and the collection was transferred to the Institute from the custodianship of Edmund Milne Jnr. The collection remained in the institute until its closure, in 1984, when it was transferred to the National Museum of Australia.

Milne avidly pursued the collection of gorgets and attempted in the process to obtain information about the people for whom they were made. Most of the information known to the museum still derives from the letters Milne received in reply to his inquiries. One of the gorgets in the collection, the gift to Coomee, ‘Last of the Murramarang tribe’, was actually commissioned by Milne (collection number 1985.0059.0374).

His method of exhibiting the gorgets in his collection room is documented in two photographs. The gorgets were mounted centrally on the wall in a framed case. They were clustered together making a decorative set in the same way that he mounted all his artefacts. Milne grouped the artefacts for artistic effect rather than pure association, although like objects were kept together. For example, spears were grouped in layered bundles and boomerangs circled in decorative patterns. The result is visual indigestion from the sheer quantity of objects.

It is a trophy room, a testimony to a hunt for large quantities of artefacts. No attempt was made to tell the individual story of each artefact nor to indicate their social history, although Milne was often aware of this and had documented it elsewhere.

Edmund Milne was a typical 19th-century romantic who revelled in the picturesque lifestyle of traditional Aboriginal Australia. He agonised over what he and many others of his kind saw as the approaching Aboriginal Armageddon. In that scenario the last ‘full blood’ Aboriginal people would lose their fight to maintain integrity as a ‘race’ succumbing to the onslaught of Anglo-imperialism.

Milne clung to his friend Coomee, and any other Aboriginal person he regarded as genuinely maintaining links with pre-colonial Aboriginal society. His interests were also pragmatic because the same people were able to help him increase his collection. For example, the Murramarang area was one of the focuses of Milne’s ethnographic collecting and Coomee was the source for at least two of his items, both of which are now in the National Museum of Australia’s collections. In 1903 Milne purchased from her an old and pitted square-edged axe from Pigeon House Mountain near Ulladulla. In 1908 he acquired a black wattlebark fishing line of Coomee’s own manufacture.

Milne collected people as well as objects. He grouped together photographs of Coomee with those of the artefacts and archaeological sites of Murramarang in his scrapbook album. The pictures and captions treat Coomee as an artefact to be studied with the other artefacts in his collection. Milne pointed out Coomee’s pierced nose and body scars in order to provide a clear provenance, as a dealer would for an artefact, of her status as an authentic ‘tribal’ Aboriginal person:

Coommee-nullanga (Maria), The last of the Lithic people of Murramurang. Reputed to be over ninety years of age. The nose septum has been pierced and the tribal ceremonial scars appear on each shoulder. [4]

The gushing, nostalgic article Milne constructed from his conversation with Coomee and his own vivid imagination praised the Murramarang people for resisting ‘that passing cloud’ which would ‘all too soon ... overshadow their native land ... the beginning of a bitter end’. [5] From the memories of her grandmother Coomee recounted to Milne the first sighting by Aboriginal people of English ships and Milne turned her account into a doomsday narrative:

Across the waste of waters three little white clouds one day dotted the horizon. The men of the Northern Steel Age were furrowing the Southern Ocean. The startled clansmen watched the cloudlets grow till they took the shape of giant birds with up-reaching, far stretching white wings. Then they broke and fled in mad stampede to hide ... old Mooroo, the age-stricken but still dreaded medicine-man of the tribe ... as the white-winged birds of ill-omen sailed past, he raised the queer, uncanny death-chant of the black men, to the accompaniment of clapping boomerangs. [6]

Milne was so convinced by his own preconceptions about Aboriginal people that he did not listen to Coomee’s important comments to him, quoted earlier [see 'Last of the Tribe']. He wrote ‘these pitifully simple words convey a great truth — partially’. [7] He allowed her ‘partial’ insight in spite of the fact that she had lived the ‘the great truth’ about which he was passing judgment. His ‘truth’ was that Aboriginal people had ceased to have a role in the world and were becoming extinct.

Milne was slavishly following the general consensus of opinion at the time that Aboriginal people were inferior to Europeans and could not compete. Popular intellectual thought from the late nineteenth century until quite recently was fuelled by the ‘dying race theory’. It was a theory developed by ‘social Darwinists’ from Darwin’s theories about the origin of species, the hierarchical structure of life forms and survival of the fittest. All this, Milne wrote, was beyond Coomee’s understanding and it was up to men like himself to see that the ‘last’ of the Aboriginal people died in blissful ignorance of the ‘Great Plan’:

Beyond the ken of Coommee lies the grim, hard, cruel fact that the task allotted to the Australian Aboriginal in the Great Plan has, in the fullness of time, been completed. Their guardianship of our island continent is finished. The Stone Age cannot blend with the Steel Age — the stone must crumble before the metal. The black man’s work is done; sooner or later he must drift across the border-line into the land of vanished peoples, and his place amongst the races of the earth will be — must be — vacant.

Let the dominant white man see to it that the drifting of the remnants shall not be hurried, so that when, in due time, an account of our twentieth century stewardship shall be called for, the miserable, cowardly, futile excuse, ‘Am I not my brother’s keeper?’ with the awful consequent indictment, will not need to be repeated. [8]

Ethnographic collections like those of Milne were made as an archive of a people and culture that was believed to be ending.

Footnotes

[1] Anon, The Milne Anthropological Collection, manuscript, National Museum of Australia, EO Milne Collection file no. 85/310 folios 198-200, nd.

[2] National Museum of Australia Milne Collection file no 85/310, folio 151.

[3] EO Milne, Extract from the last will and testament of Edmund Milne dated 12 December 1916.

[4] EO Milne, ‘The passing of the lithic people: a story of the coming of white wings to Australia’, Life, 1 April 1916, p. 301.

[5] EO Milne, ‘The passing of the lithic people: a story of the coming of white wings to Australia’, Life, 1 April 1916, p. 301.

[6] EO Milne, ‘The passing of the lithic people: a story of the coming of white wings to Australia’, Life, 1 April 1916, p. 300.

[7] EO Milne, ‘The passing of the lithic people: a story of the coming of white wings to Australia’, Life, 1 April 1916, p. 303

[8] EO Milne, ‘The passing of the lithic people: a story of the coming of white wings to Australia’, Life, 1 April 1916, p. 304.