Criteria for selection

The Russian explorers observed that Bungaree was one of a number of Aboriginal people who the colonial government had attempted to manipulate into positions of dominance over the wider Aboriginal community.

They observed that the colonial government bypassed leadership choices made by the Aboriginal communities and selected their own preferred leaders. The government then conferred the distinction of a gorget on their chosen leaders, making the title official.

The main criteria for selection were the person’s loyalty and usefulness to the colonists:

They live in societies of 30, 40, 50 or more persons, and are ruled by their own elders. Nowadays the English Government itself selects the elders and gives them a special mark to that effect consisting of a copper plate on which their rank is indicated, and which they wear round the neck. [1]

The elders of the native groups are distinguished by copper signs with an inscription giving their name and the place where they mostly reside; these they wear by a copper chain at their chest. The elders are sometimes useful to the government in cases of pursuit of, or searches for, escaped convicts.

The government gives them boats for fishing and to facilitate their movements across water. ... Until the coming of the English their government was patriarchal, each community was ruled by the senior man. But various English Governors have thought fit to select the chiefs themselves.

The dignity and the division of the above-mentioned sign worn round the neck are bestowed on those who show most attachment to the English. ... Such arrangements have been introduced in order to accustom the natives to submission and, through them, to learn of escaped convicts. In this respect they are extremely useful, for they act as guides to military detachments or the police. [2]

Traditionally, Aboriginal societies did not have kings or chiefs in the sense used by English-speaking people. However, elderly and senior initiated men were held in high esteem and physically, spiritually or intellectually superior men were also able to command significant respect. Men of high esteem were looked to by the community for advice and leadership in public matters.

Respected men

When the colonists searched for leaders among the Aboriginal people, in order to find influential allies, they saw in those respected men the qualities they recognised as the badges of leadership in their own society. Some colonists recognised that in spite of the respect and influence those men commanded they were not regarded as solo leaders while other colonists made the simple equation and labelled the men ‘chiefs’ or ‘kings’.

Even the sceptics used the useful label ‘chief’ to describe the men they formed alliances with in order to promote them within both the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal communities.

William Romaine Govett gave a typical early 19th-century assessment of Aboriginal social hierarchy:

Each tribe has a chief; but whether he possesses his authority from hereditary right, or is chosen, as being the most active and strong, the most valorous or warlike, or from any particular achievement, is not known. It may be observed, however, that they are in general the finest men; and though they are not distinguished from the rest in outward appearance or clothing, they alone have the privilege of having two wives.

... Every tribe possesses its own peculiar territory, and they appear to be very jealous of any invasion of their boundaries, which is often the cause of warfare between one tribe and another ... the chief exercises his authority in various ways: he has the power to disperse the tribe, to order their movements, and appoint the time when, and place where, they are all to assemble again. Sometimes the men hold a council of war, — for I have seen the oldest of them, to the number of thirty, sitting round in a circle (apart from the women and youths), talking apparently very seriously, as if they had heard a report of the approach of a hostile tribe, or some other cause of fear; and, after an hour’s deliberation, the whole tribe has separated in parties of six or four, but the chief remaining with the women.

These parties appear to act as piquets on the look out, observing, and at the same time can easily communicate with one another. In this manner they remain away for several days, nor do I think that they assemble again until the regular time appointed by the chief. [3]

In ‘the district named Tarlo’, near the Wollondilly River [4], Govett and ‘another gentleman’ had heard that a ‘tribe’ of Aboriginal people was in the neighbourhood and they decided to visit them at night. They ‘went from one fire to another in order to observe the particular actions and employments of the several groups or families.

The chief was sitting cross-legged between his two wives, and smoking a short black pipe. He was naked, with the exception of the belt around his waist; upon which was inscribed his name, &c., and he appeared, as the light of the fire was reflected upon him, a strong and muscular man’. [5]

Louisa Meredith, who spent time in the Bathurst district in the early 1840s, observed that Aboriginal people respected and gave special consideration to elderly or physically powerful men:

The natives pay great respect to old age; that, and valour, comprising the only distinctions of rank allowed among them. The best fighting man is the chief or head of his tribe, and in case of his death, the next best takes his place, and inherits his wives. The other warriors and the old men form a sort of council, which is convened as occasion demands, when peace, war, and all other points of importance are discussed and decided upon. [6]

In the early 1840s Leon Ducharme, a Canadian who spent four years in New South Wales as a political prisoner, observed that gorget-wearing kings were a common sight. Interestingly, he commented that the gorget was a continuation of a traditional sign of leadership.

However, he said nothing more on this and no further information has been found. He may have been referring to body scars made during the stages of traditional initiation into manhood and its senior levels:

Each tribe has its king whose distinctive mark is a little copper plate in the shape of a half moon, which hangs round his neck, and on which is written the name of his tribe. This mark of distinction is given them by the colonists. Formerly they had a mark made by themselves, one somewhat of the same shape as that of to-day. These kings are often to be seen at the head of a party of their subjects going hunting. [7]

Even in densely settled areas some Aboriginal people continued to hold sway over their own country or a diminished part of their country. Some became farmers and participated in the cash economy of the colony.

Many of those small farming communities were led by a senior Aboriginal man who was given the title king or chief by the local non-Aboriginal population and presented with a gorget.

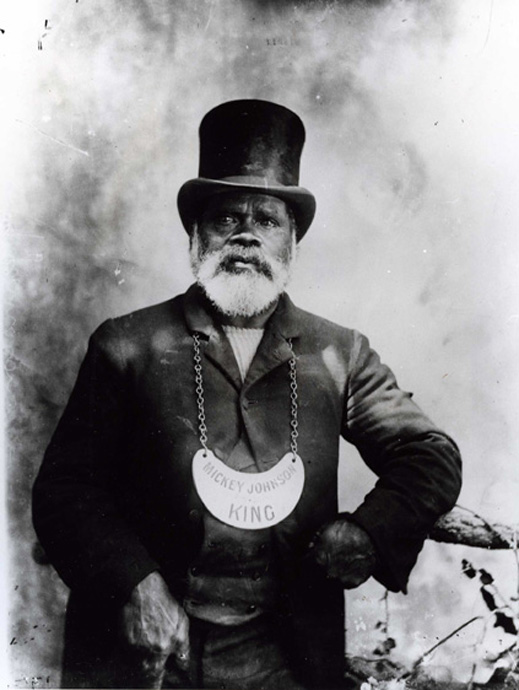

Mickey Johnson

Mickey Johnson, who was photographed as a very smartly dressed man wearing a large gorget which simply declares him as ‘king’, held sway in one of the most fertile farming areas in New South Wales, the Illawarra district.

He was ‘crowned’ at a well-attended public ceremony in Wollongong on 30 January 1896.

Billy Kelly, King of Broadwater

Billy Kelly was the senior man in the farming community at Cabbage Tree Island near the mouth of the Richmond River, and he was given a gorget and the title ‘King of Broadwater’ by the local non-Aboriginal population.

Billy’s gorget is now held by the National Museum of Australia (collection number 1985.59.367) and some of his history can be recovered from the associated files.

In 1911, Edmund Milne, who collected Billy’s gorget, received a letter from Edward Reid at the Cobar police station which gave some details of his life. Billy appears to have been comparatively successful in adapting to colonial society.

By exploiting some of the resources provided by local farmers Billy maintained his own independence and that of his community. The fact that he was presented with a gorget indicates that at some point Billy Kelly was recognised as a man of considerable influence:

Now as regards ‘King Billy’, I shall give you his particulars as near as possible. The seat of ‘His Majesty’ was Cabbage Tree Island, which is situate on the Richmond River about 14 miles from the Heads, and about 1 1/2 miles from Broadwater.

... The Island is a very fertile one, and contains about twenty Farms of about 10 Acres each, dedicated to, and occupied by Aborigines, who depend upon Sugar cane, Maize Etc for their support, ‘Billy’ reigned there for about 13 years, prior to that, he lived at the foot of Cook’s Hill, about quarter of a mile South of Broadwater, and within about 1 mile from the sea beach, his territory embraced the whole of the Lower Richmond commencing at the mouth of the Little River which runs into the Sea, following the Eastern bank of the river to Woodburn, thence in a Northerly direction through Tuckean Swamp to Meerschaum Vale Range, thence to Uralba and Newrybar, (still northerly) to the 7 mile Beach, which lies centre way between Ballina and Byron Bay, so you will observe, that his territory had an enormous sea frontage.

... Billy died in January 1902, and was a widower, and the following facts may be interesting, about the year 1880, Billy, like many other foolish old men, took unto himself a young Gin, who was of a roving disposition, which Billy strongly resented, and in one of his jealous fits, went so far as to hamstring her, so as to keep her within the precincts of his home, however, she died some 5 or 6 years later and was buried on the sea shore.

... Some years afterwards when stationed in Wardell, I was informed that there were some human bones on the beach, and upon investigation, I found the skeleton of ‘Hopping Molly’ that being the name she was known by, the identification rested upon the old residents of the place, who upon being shown the thigh and shin bone which was shaped thus, (diagram) declared it to be the leg of Hopping Molly, the knee joint having become completely ossified, which caused her to hop, and from which she derived her name.

... This was one of the best curios I ever saw, and was very much coveted by one Dr Forbes, who was then practising in Wardell, who never ceased to worry me for same, until I finally decided to give it to him, a matter I very much regretted ever since, as I should never have separated it from the plate (punctuation as in original). [8]

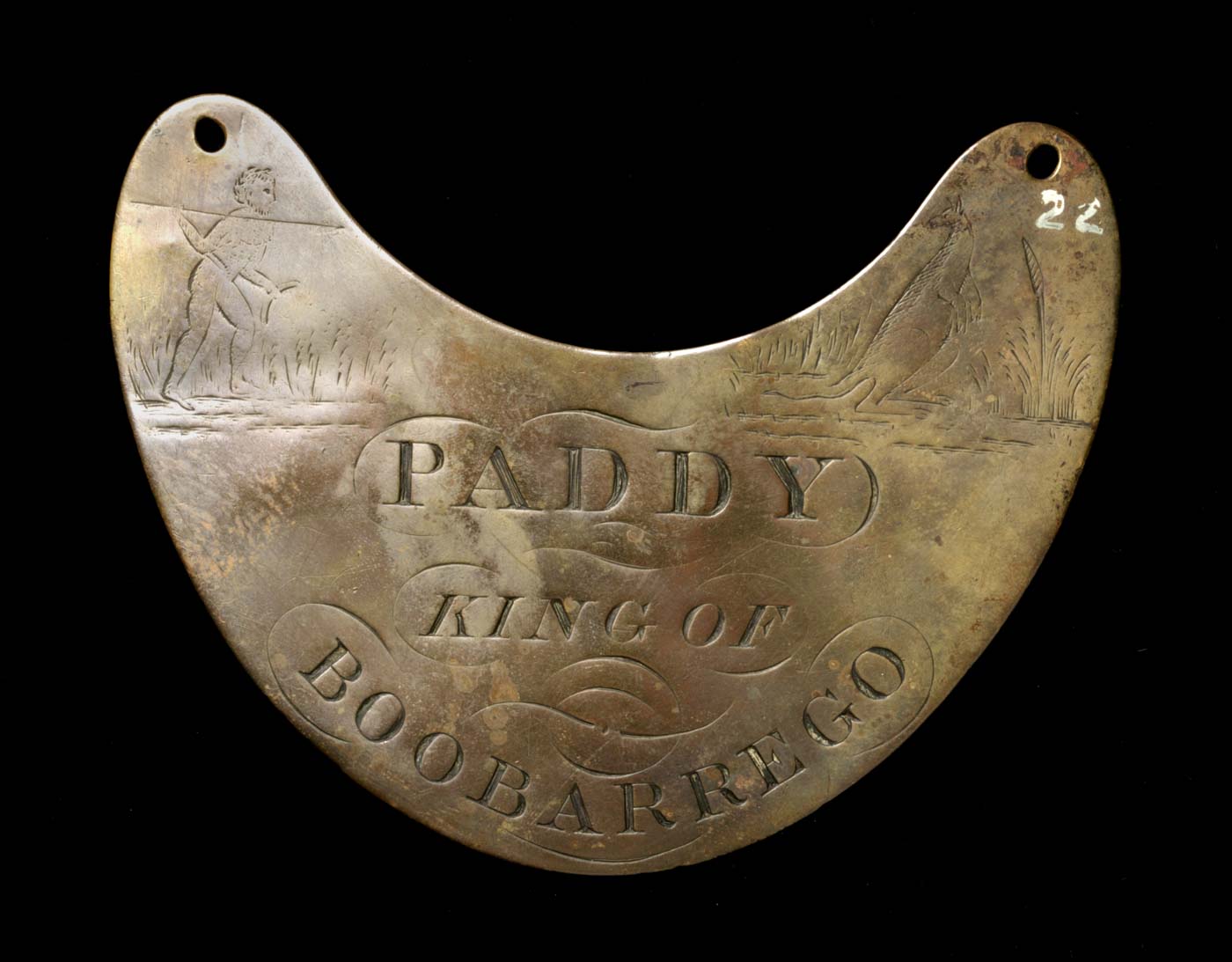

Paddy, King of Boobarrego

Another leader within a farming community was Paddy, who was given the title ‘King of Boobarrego’. Paddy, like Billy, provided himself and his community with produce from the resources made available, not always willingly, by local farmers.

He was made king when the people of the Orara River district were still living a traditional lifestyle. Paddy may have been given his gorget by a settler who wanted to obtain some influence with the local people.

The settler may have been the ‘best friend’ from whom Paddy regularly stole vegetables. Paddy’s gorget is now held by the National Museum of Australia (collection number 1985.59.368) and once again a letter to its original collector, Edmund Milne, provides us with a little of the recipient’s history. In 1911 R Duggan wrote to Milne from Ulgundalu Island:

Paddy was about 80 or 90 years old when he died he reigned over about 70 of his own people teaching them to take turnips and other vegetables from the Garden of their best friend when unseen. He was quite strong and active to the last died of a cold ill a fortnight. His Dominion extended about 10 miles up and down the Orara River 7 miles south of Grafton.

... There are a few of his descendants still living and they are learning to know a better way, but still look back to the old times. ... This is as much as I can get from them they do not seem to know much they were quite wild in those days and Jessie has no idea of dates or years.

... The old man that has the plate will not part with it even to be photographed or in such good company. I am sorry but he gets quite angry if I suggest it now ... [9]

Footnotes

[1] Novosil’sky 1820, in G Barratt, The Russians at Port Jackson: 1814-1822, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1981, p. 29.

[2] Bellingshausen 1820, in Barratt 1981, p. 39.

[3] WR Govett, A Potts and G Renard, Sketches of New South Wales Written and Illustrated for the Saturday Magazine in 1836-37 by William Romaine Govett, together with an Essay on the Saturday Magazine by Gaston Renard and an Account of His Life by Annette Potts, Gaston Renard, Melbourne, 1977, p. 15.

[4] WH Wells, A Geographical Dictionary; or Gazetteer of the Australian Colonies, 1848, Effingham Wilson, London, 1851, p. 15.

[5] Govett et al, 1977, pp 28-29.

[6] LA Meredith, Notes and Sketches of New South Wales During a Residence in that Colony from 1839 to 1844, John Murray, London, 1844, p. 96.

[7] L Ducharme, Journal of a Political Exile in Australia, translated and with notes by G Mackaness, DS Ford, Sydney, 1845 (1944), p. 45.

[8] E Reid, letter from Edward Reid to Mr Milne, 13 October 1911, manuscript, National Museum of Australia, EO Milne Collection, file no 85/310, folio 154.

[9] R Duggan, letter from R Duggan to Mr Milne, 1911, manuscript, National Museum of Australia, EO Milne Collection file no 85/310 folio 157.