Leaders of the Aboriginal community

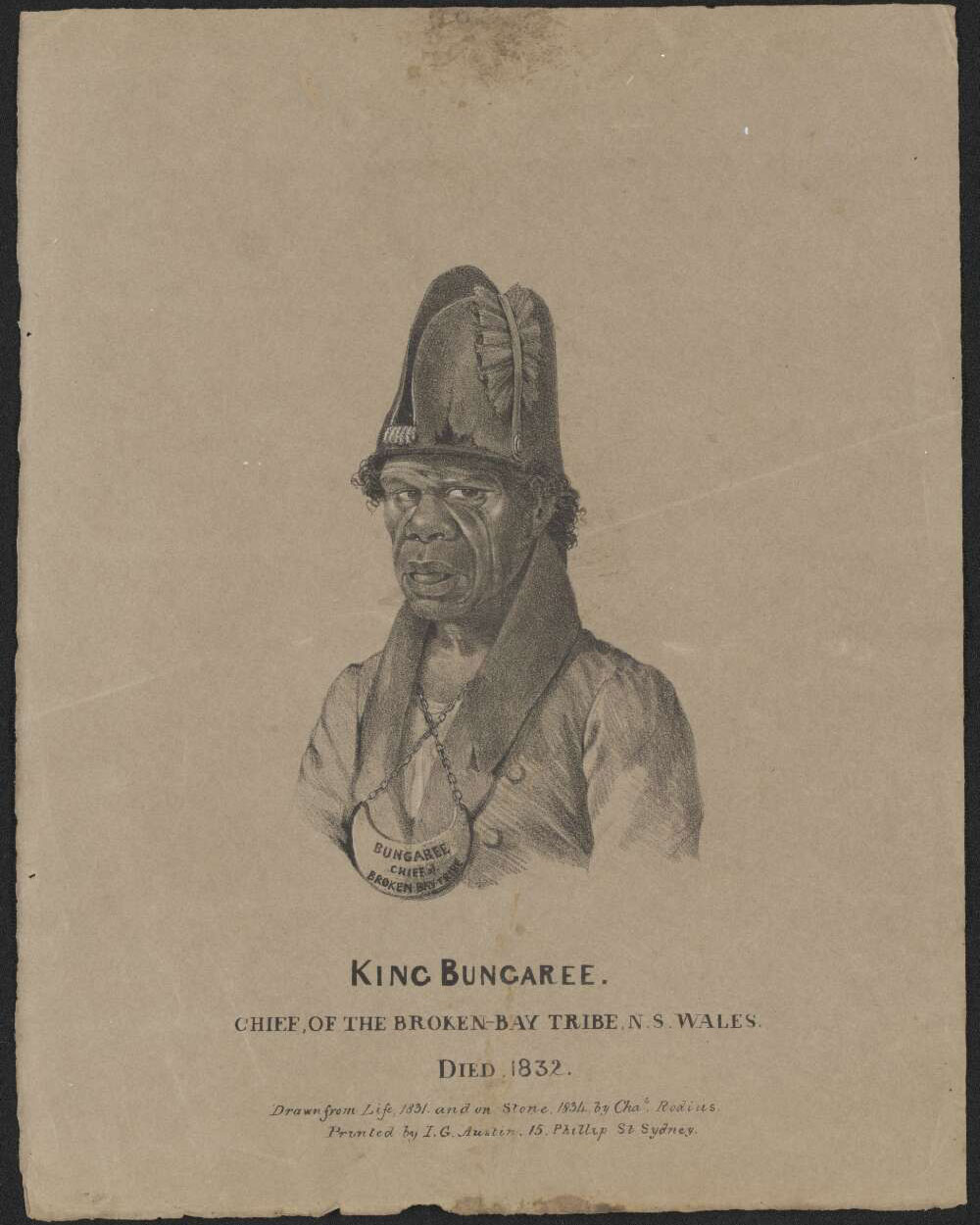

King Bungaree and Queen Gooseberry were two of the best known people in Sydney during the governorship of Lachlan Macquarie, in the early 19th century.

Macquarie presented both of them with gorgets to mark their status as leaders of the Aboriginal community and importance within the wider community of Sydney. The couple were often sketched and painted during their lifetime.

In most of the surviving pictures of Bungaree, he wears his gorgets, officer’s coat, trousers and cocked hat while Queen Gooseberry is draped in a government blanket:

Boongarie was remarkable for his partiality for the English costume ... he ... arrayed his person in such shreds and patches of coats and nether garments as he could by any means obtain; the whole surmounted by an old cocked hat. ... Commodore Sir James Brisbane was particularly partial to him, and on one occasion presented him with a full suit of his own uniform, together with a sword, of which he was not a little vain. [1]

Bungaree’s wife was given the English name ‘Queen Gooseberry’ but her Aboriginal name was Matora. [2] [Editor's note: Closer examination has shown that Matora and Gooseberry were not the same person. They were different people, both were wives of Bungaree. Matora predeceased Bungaree, who died in 1830, while Gooseberry lived for another two decades, living until 1852. A good source of information about Bungaree, Matora and Gooseberry is Keith Vincent Smith’s book King Bungaree. A Sydney Aborigine meets the great South Pacific explorers, 1799–1830, published in 1992].

Gooseberry was the only person known to have been given two gorgets, although future research may find other cases.

One of her gorgets is only known through a photograph in Frederick McCarthy’s article about gorgets. [3] The picture shows a very worn, crescent shaped, older style gorget decorated with a design of two fish either side of a central coronet, beneath which is the inscription ‘Gooseberry, Queen of Sydney to South Head’.

The other gorget is now held in the Mitchell Library, Sydney and is an undecorated crescent-shaped gorget made from copper with the inscription ‘Cora Gooseberry, Freeman Bungaree, Queen of Sydney and Botany’.

[4] Unfortunately, in spite of her special status, surviving descriptions of [Gooseberry] are tainted with cultural bias: ‘His wife, an old woman smeared with fish oil, was truly the personification of ugliness — but meeting one in the bush she always asked to be kissed’. [5]

.

Remembering Bungaree

In his obituary, Bungaree was titled ‘his Aboriginal Majesty King Boongarie, Supreme chief of the Sydney Tribe’. [6] Captain Faddei Bellingshausen of the Vostok described Bungaree in 1920:

Boongaree ... is about 55 years old; he has always been distinguished by a kind heart, gentleness, and by other good qualities and has been of service to the colony. ... He has frequently put his own life at risk in order to re-establish peace among the groups which are under him. [7]

Ivan Simonov, astronomer on the Vostok commented:

... seven more New Hollanders approached us ... led by a man of about 55 wearing a shabby yellow jacket of the English convict’s type and a torn pair of sailor’s trousers. His proud step and bearing indicated an important personage. At his chest, there shone a copper plate in the shape of a half-moon, with the inscription: ‘Boongaree: Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe: 1815’. The plate hung round his neck on a copper chain. ... From the copper plate itself it was obvious that the man’s name was Boongaree, and that he was regarded as the chief of the Broken Bay Tribe. The man approached us in company with his hideous wife whose name was Matora. [8] [see Editor's note above on Matora and Gooseberry]

Bungaree's breastplate

The location of Bungaree’s gorget, if it still exists, is no longer known. However, from pictures made at the time and descriptions it seems the gorget was crescent-shaped and inscribed ‘Bungaree, Chief of the Broken Bay Tribe, 1815’. The Russian explorers who met Bungaree in 1820 claimed it was made from copper and hung around his neck on a red copper chain.

[9] However, a later source claimed it was brass, suspended on a brass chain and inscribed ‘Bungaree, King of the Blacks’, being decorated with ‘the arms of the colony of New South Wales, an emu and a kangaroo’. [10] It is possible also the Bungaree had two gorgets.

Bungaree may have been the first Aboriginal person to be presented with a gorget because he had a long history of service with naval explorations undertaken by officers associated with the colony:

He ... accompanied the late Captain Flinders, both in the Norfolk, sloop to Moreton Bay, and in His Majesty’s ship Investigator to the Gulph of Carpentaria. He also accompanied Commander James Grant in H.M. Colonial Brig, Lady Nelson to Port Macquarie ... he was with Commander P.P.King in the Mermaid, on its voyage to the north-west and tropical coasts of Australia. [11]

Bungaree was also a key person in Macquarie’s plans to ‘civilise’ the Aboriginal population. Bellingshausen explained that Macquarie had hoped first to convert Bungaree to the ‘benefits’ of living a ‘civilised’ lifestyle and then use him as an example to other Aboriginal people.

However, Bungaree had little incentive to pursue Macquarie’s ideal. He was lured away from farming by the fast life in Sydney and the easy access it provided to spirits and tobacco. His powers of leadership were doubtful in any case as he was often set upon by other Aboriginal people:

Wishing to turn the natives of New Holland from their nomadic existence and to accustom them to a fixed abode, Governor Macquarie had given Boongaree a specially built little house with a garden in Broken Bay. He had named him chief of the area and placed around his neck the copper plaque with the inscription, ‘Chief of Broken Bay’. But the magical allurements of spirits and tobacco, for which the natives have passions, prove stronger than all the delights of a fixed, plentiful, and quiet life, and constantly entice the natives to the neighbourhood of Sydney town. ... Boongaree and his family have a boat, given by the government; and other New Hollanders have likewise been given boats by inhabitants of Sydney on the condition that they surrender part of their daily catch of fish.

They go out in these boats every day, fish at the mouth of the Bay, and then hasten back to the town to surrender the due portion of the catch; the remainder they exchange for drink or tobacco. Returning from the town to their dwellings on the northern shore the natives had to pass by our sloops, and every evening they went back drunk, shouting awfully and threatening each other. Sometimes their quarrels ended in a fight. ... One morning Boongaree came to the sloop to barter fish for a bottle of rum. To my question, ‘Who broke your head?’, he replied with indifference, ‘My people when they were drunk’. It was clear enough from this how much power he had over those whom he called his people. [12]

Bungaree in Sydney society

Bungaree established himself in Sydney as an important identity on his own terms and used Macquarie’s gifts as they suited his chosen lifestyle. The extensive settlement and subsequent degradation of the environment in and around the colony meant that Bungaree and other Aboriginal people were unable to maintain their traditional economy. However, they adapted themselves to the changed environmental and cultural conditions.

In 1815 Bungaree was placed in charge of 16 families at Georges Head who were to farm the land with agricultural implements supplied by the government and with help from convicts who were ‘obliged to teach them agricultural skills’. For some time the people were successful on their farms and for many years the peaches that grew on Bungaree’s land provided him with a steady income. [13]

Visitors to the colony often commented on Bungaree who made it his business to greet anyone important who was new in the colony. He made a lasting impression on the Russian expedition that was ashore in Sydney between March and April 1820.

Bungaree found that they were generous with his favourite drink, rum, and for their kindness included them amongst his friends. [14] He used his powers as a mimic to help establish himself as an identity in Sydney. His speciality was imitating the governors and he modelled himself on their manners and dress:

His majesty changed his manners every five years; or rather they were changed with every administration. Bungaree like many of the Aborigines of New South Wales, was an amazing mimic ... now as the Governor for the time being was the first and most important person in the colony, it was from that functionary that King Bungaree took his cue. And, after having seen the Governor several times, and talked to him, Bungaree would adopt his Excellency’s manner of speech and bearing to the full extent of his wonderful power. [15]

Footnotes

[1] Anon, ’Death of King Boongarie, Sydney, Saturday, 27 November, 1830 in Chapman Ingleton, G (ed.), True Patriots All, or News from early Australia - as Told in a Collection of Broadsides, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1952, p. 122.

[2] Simonov 1820, in G Barratt, The Russians at Port Jackson: 1814-1822, Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, Canberra, 1981, p. 49.

[3] FD McCarthy, ‘Breast-plates: the Blackfellows’ Reward’, The Australian Museum Magazine, 1952, vol. 10, p. 328.

[4] McCarthy, p. 331.

[5] Novosil’sky 1820, in Barratt, 1981, p. 29.

[6] Anon 1830.

[7] Bellingshausen 1820, in Barratt, 1981, p. 44.

[8] Simonov 1820, in Barratt 1981, p. 49.

[9] Novosil’sky 1820 and Simonov 1820, in Barratt 1981, p. 29 and p. 49 respectively.

[10] Anon, ‘Memoir of Bungaree in the Australian Home Companion (1859)’ in Chapman Ingleton, G (ed.), True Patriots All, or News from early Australia – as Told in a Collection of Broadsides, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1952, p. 268.

[11] Anon 1830.

[12] Bellingshausen 1820, in Barratt 1981, p. 36.

[13] Bellingshausen 1820, in Barratt 1981, p. 44.

[14] Novosil’sky 1820, in Barratt 1981, p. 29.

[15] Anon 1859.