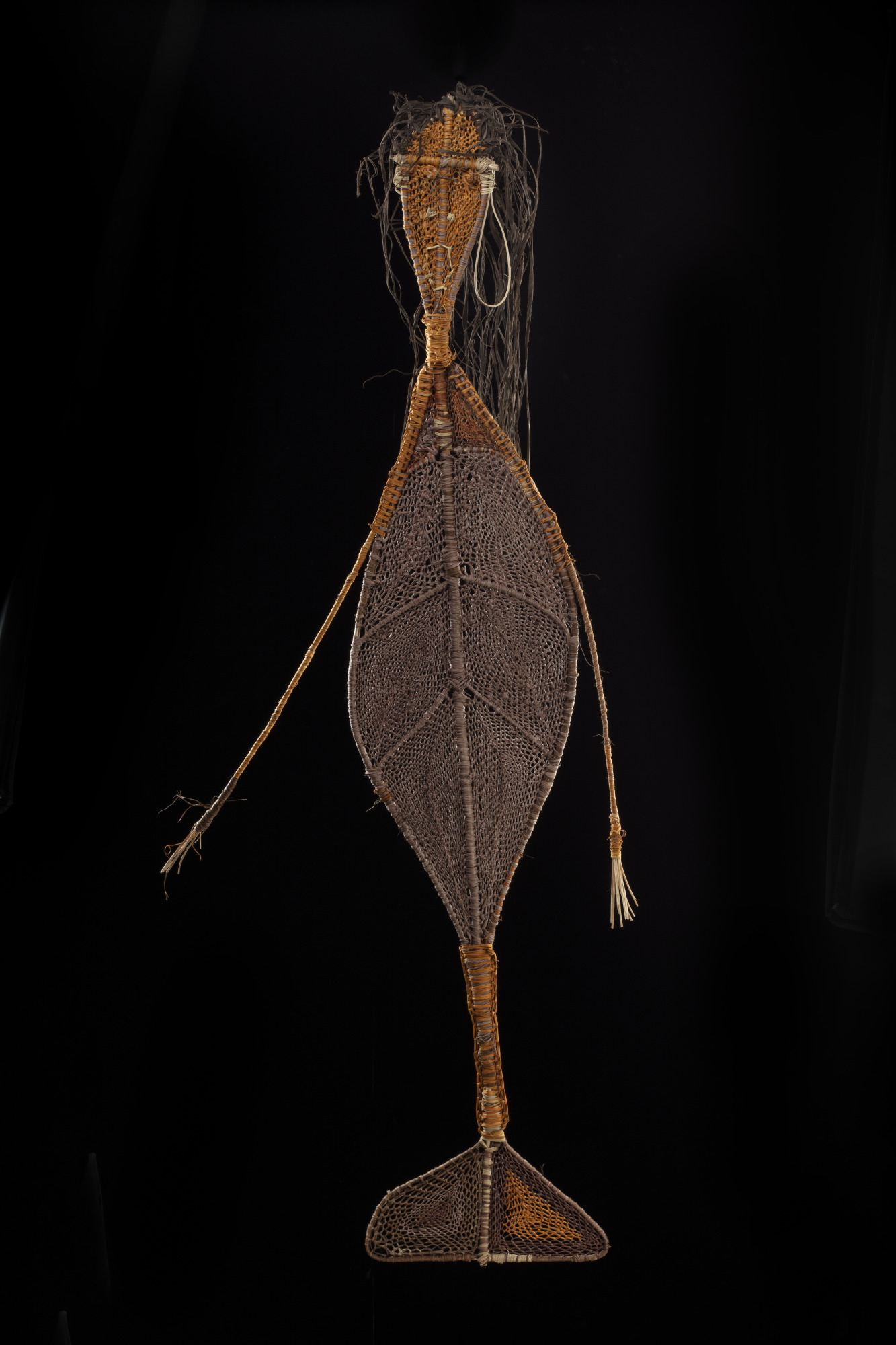

This collection of Yawkyawk sculptures depict young female Ancestral Beings found in the freshwater pools and streams of Western Arnhem Land in Australia's Northern Territory.

Made by Kuninjku artists at Maningrida, the Museum's collection includes some of the earliest forms of Yawkyawk sculptures, showing the evolution of ancient techniques of weaving into new artistic directions.

Ancestral Beings of Arnhem Land

Yawkyawk inhabit the freshwater pools and streams of Western and Central Arnhem Land. Often compared to mermaids, Yawkyawk have the head and torso of a woman and the scaly body and tail of a fish. Their long flowing hair may appear as trailing blooms of green algae.

As water spirits, Yawkyawks protect the billabongs, streams and waterways. They have influence over the weather and are closely associated with Nyalyod, the Rainbow Serpent, a powerful creation Ancestor.

In Bininj Kunwok languages, the word Yawkyawk means ‘young woman’ and ‘young woman spirit being’. In Kundedjnjenghmi language, she is known as Ngalkunburriyaymi.

Yawkyawk and Ngalyod, the Rainbow Serpent

Kuninjku believe that Yawkyawk were once alive as young sisters, who travelled between clan estates. They carried a digging stick and a sacred string, searching for food. One night they camped by a deep waterhole and lit a fire for cooking. But the fire was too close to the waterhole, which angered Ngalyod, the great Rainbow Serpent.

Ngalyod burst through the surface of the water and swallowed the sisters whole. They are ancestor spirits now and their sites are closely connected to the Rainbow Serpent. Yawkyawk are active to this day, protecting the ecology of the waterways that sustain life across the Arnhem region.

Yawkyawk are amphibious spirits, residing beneath the surface of the freshwater pools and streams. They occasionally rise to the surface to sun themselves on the banks or grow legs and walk through the camp at night, calling out loudly and eating yams and sugarbag.

From beneath the water, Yawkyawk sing to themselves, and Kuninjku people can hear them, while fishing or passing by.

Shapeshifters

Yawkyawk are endowed with spiritual powers and the ability to shapeshift. Apart from their close association with Ngalyod, they can also manifest as freshwater turtles, dragonflies or beetles. Yawkyawk can bring inclement weather to those who displease them. They are both feared and revered and visitors should approach their sites with caution.

Yawkyawk sites are associated with fertility. Swimming at a Yawkyawk site may cause conception for women who enter the water. Yawkyawk have babies of their own kind, depicted in some sculptures, including Dorothy Bunibuni's 2022 work.

Maningrida makers

In 2006, the National Museum of Australia acquired three woven Yawkyawk sculptures by Kuninjku artists Marina Murdilnga and Lulu Laradjbi. These were considered to be among the first figurative woven sculptures made in the region.

In the early 2000s, women artists at Maningrida Arts and Culture Centre, led by Murdilnga, experimented with using weaving techniques such as knotting and looping stretched over a frame to create representational sculptures.

Knotting and looping techniques have been used for millennia by Kuninjku women to construct utilitarian objects including woven mats, dilly bags, fish traps and baskets. The technique of coil basketry is thought to have been introduced by missionaries in the 1920s, who brought coil weaving techniques from south-eastern Australia.

When Murdilnga made the first woven Yawkyawk sculpture in 2003, she inspired her contemporaries and future generations of female artists to evolve the ancient techniques of weaving into new artistic directions.

Pandanus and the earth's palette

These woven Yawkyawk sculptures are created entirely from materials harvested by the artists from their country and clan estates. Collecting pandanus (Pandanus spiralis) is challenging physical labour, with the artists using machetes to hack down the jagged leaves. Working under the steamy tropical sun, green ants and spiders rain down from the canopy above.

Using their bare hands and expert touch, women shred the pandanus and leave it to dry for several months. They use their extensive knowledge of the environment to create natural dyes using ochres, roots, leaves, wood ash and charcoal. By adjusting dying techniques and immersion times, a dazzling array of colours is achieved, ranging from luminous yellow and velvety purples to sunset hues of pink, red and orange.

Only after this intensive period of preparation can the weaving begin, meaning it can take more than a year for an artist to create a Yawkyawk sculpture.

Evolution of Yawkyawk artworks

Representation of Yawkyawk Ancestral Beings have evolved from depictions on cave walls, to bark paintings made by senior male artists such as Peter Marralwanga and Mick Kubarkku from the 1970s to the 1990s.

The Museum's collection comprises three sculptures made in 2005 and two made in 2022, illustrating the evolution of artistic practice at Maningrida community. While the earlier sculptures use a loose weave and represent Yawkyawk as waif-like creatures with a powerful gaze, those made in 2022 tend towards more elegant and expansive forms with gleeful grins and a playful aura.

Yawkyawk are also depicted in paintings and fabric prints in the Museum's collection.