The Bealiba gold nugget was found near the town of Bealiba (70 kms west of Bendigo, Victoria) on 26 June 1957 by Arthur Stewart, the owner of a small nearby grazing property. Mr Stewart had stopped at the side of the road to repair the chain on his bicycle, which he was riding because his car had earlier broken down.

His bad luck ended, however, when he noticed gold glinting from a clod of earth alongside the road. He dug the 22-ounce nugget out with his hands, then washed it in a nearby stream to confirm he had discovered gold.

The next day Mr Stewart formed a syndicate with mail contactor Gordon McDowell and a farmer and his son both named Tom Wright. They called their syndicate 'Stewart's Surprise', took out miner's rights and pegged a claim around the spot where the nugget was found.

The discovery caused a minor gold rush with people arriving from surrounding areas eager to find more gold. On 1 July, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that hundreds of people were fossicking around Bealiba with picks, shovels and pans.

Although the Victorian goldfields were famed for the gold nuggets that they yielded, including some of the largest ever discovered, very few of these survive in their original form. Soon after being discovered most nuggets were melted down so that the gold could be weighed and sold.

A few months after the Bealiba nugget was discovered it was purchased by the Australian Amateur Mineralogist, a magazine that 'advocated for the retention of more of Australia's magnificent specimens for the sake of future generations'.

The National Museum of Australia purchased the nugget in 2011. It helps tell the story of the impact that gold had on Australia and Victoria.

Curator Stephen Munro tells the amazing story of the discovery of the Bealiba gold nugget − a full century after the Victorian gold rush, as part of the Object Stories project.

Colonial beginnings

In 1850 Victoria was known as the Port Phillip District, an administrative division of the colony of New South Wales. The population of the district was about 77,000 and the main economic activity was wool growing.

Many Indigenous people, whose ancestors had lived in the region for countless generations, remained in the area, but by this time they had mostly lost control of their land.

Melbourne, although still a relatively small pioneer settlement, had grown steadily since its foundation in 1835, and the city's leaders were so confident in the district's future that they had waged a 10-year campaign lobbying for its separation from New South Wales.

On 5 August 1850 a British Act of Parliament separating Victoria from New South Wales was signed by Queen Victoria, and the separation was formalised when the New South Wales Legislative Council passed enabling legislation on 1 July 1851.

By this time, gold had been discovered beyond the Blue Mountains in Ophir, near Bathurst, New South Wales, and the rush that ensued included many individuals from Victoria.

Fearing a loss of labour, economic downturn and a lowering of property values in Victoria, Governor La Trobe assembled a Gold Discovery Committee on 9 June 1851, which offered a £200 reward to anyone who found payable amounts of gold within 200 miles of Melbourne.

This was soon claimed, and the rush to central Victoria began with a number of new goldfields opening up throughout the early 1850s.

Gold rush

The discovery of gold in Victoria changed the fledgling colony forever. It soon overtook New South Wales as the main producer of gold in the Australian colonies, and news of the discoveries quickly spread overseas.

The gold rush period had a massive impact on Australian and Victorian society in terms of population, demography, economics, social hierarchy, popular culture and a sense of Australia's place in the world.

New towns and cities sprung up and Melbourne grew from a small settlement to one of the richest cities in the world.

The shallow alluvial deposits first discovered at Ballarat in 1851 were the basis of the initial Victorian gold rush but these were soon exhausted and the rush was relatively short lived.

A second boom, however, soon sprang up after miners discovered gold in the alluvial deposits associated with ancient, long buried rivers.

The method used to reach these buried rivers was deep lead mining involving the sinking of shafts, often hundreds of feet deep. Deep lead mining was a major undertaking, and this led to the population in Ballarat becoming less transient, with the wealth of the gold discovered reinvested locally.

Shaft sinking was a virtually impossible job for a single person, so miners were forced to organise themselves into co-operative groups in order to continue mining.

Because sinking shafts was such a time-consuming exercise, deep lead miners had to wait sometimes months before the possibility of finding gold, unlike surface fossickers who could strike gold at any time.

Meanwhile, each miner remained subject to the government's mining tax. This created an atmosphere of discontent in the deep lead mining regions, which contributed to the armed rebellion in 1854 known as the Eureka Stockade.

Following a meeting of miners on 29 November 1854 expressing outrage over how the goldfields were managed, a stockade was constructed at Eureka, with miners swearing allegiance to the rebel 'Southern Cross' flag.

Several days later, the authorities stormed the stockade, killing around 20 diggers. There was widespread support for the miners' cause, however, and the Eureka Rebellion ultimately led to social change across all the Victorian goldfields.

In Bendigo, quartz reefs were mined after the shallow alluvial deposits were exhausted. At first, quartz outcrops at the surface were exploited using hammers and picks, but soon the reefs were followed underground, eventually to depths of thousands of feet.

Like Ballarat, this time-consuming mining method led to a less transient population and the forming of companies to provide the necessary labour and capital for what was an increasingly difficult process.

The Museum's Victorian Goldfields collection includes a range of objects reflecting the methods used for gold mining in the late 1800s. For example, ladders, safety hooks and compact picks able to be used in the confines of an underground tunnel.

Artist of the goldfields

Samuel Thomas Gill, born in England in 1818, was employed in London as a draftsman and watercolour painter before migrating, with his parents, brother and sister, to South Australia in 1839. In Adelaide he opened a studio where he produced portraits and drew pictures of animals and buildings.

Later, in 1846, Gill went without pay as a draftsman on the ill-fated expedition led by explorer John Horrocks to the Lake Torrens region. Horrocks died tragically on the expedition from wounds inflicted when his gun accidently discharged.

Gill’s sketches and watercolours provided a narrative of the expedition and many of these are now housed at the Art Gallery of South Australia.

In 1852 Gill moved to the Victorian goldfields and although he continued to paint other subjects throughout his career, he remains best known for his depictions of everyday life on the goldfields, becoming known as the 'artist of the goldfields'.

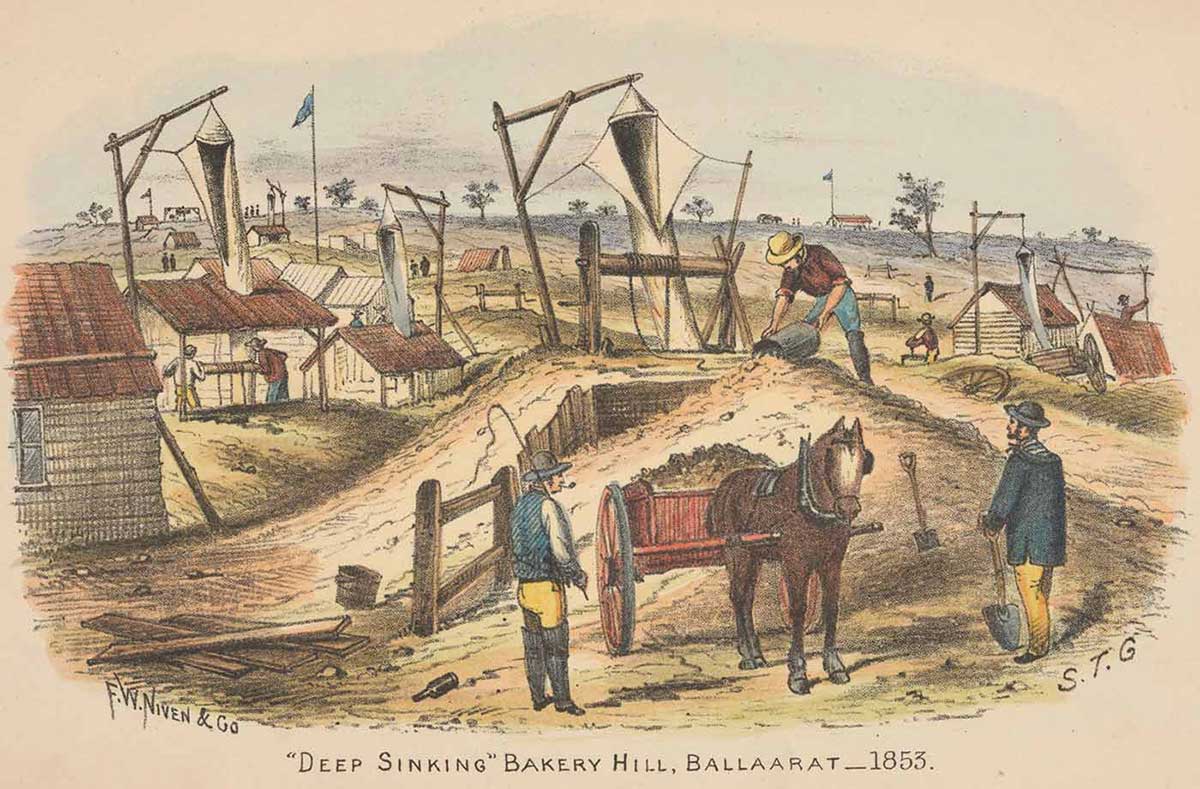

In 'Deep Sinking' Bakery Hill, Ballarat − 1853, the typical method of deep lead alluvial mining in Ballarat is illustrated, with a miner emptying the contents of a bucket hoisted by a windlass from an underground shaft, and windsails positioned to ventilate the shafts. The more prosperous shafts had shanties built around them to shelter the workers from the elements.

The Museum also holds a print titled Prospecting, purportedly by American artist William Thomas Smedley. The image appeared in the lavish publication Picturesque Atlas of Australasia, which Smedley worked on as an illustrator.

Despite its name, this publication was not an atlas, but a three-volume illustrated history of settlement in Australasia, published to coincide with the centenary of settlement at Port Jackson. It proved remarkably popular, and its engravings are still used today by researchers, historians and filmmakers to illustrate certain aspects of Australian history.