This is one of three breastplates presented to the Yandruwandha people of Cooper Creek, who assisted explorers Robert O'Hara Burke, William John Wills and John King when they returned from the Gulf of Carpentaria in April 1861.

Cross-cultural exchange

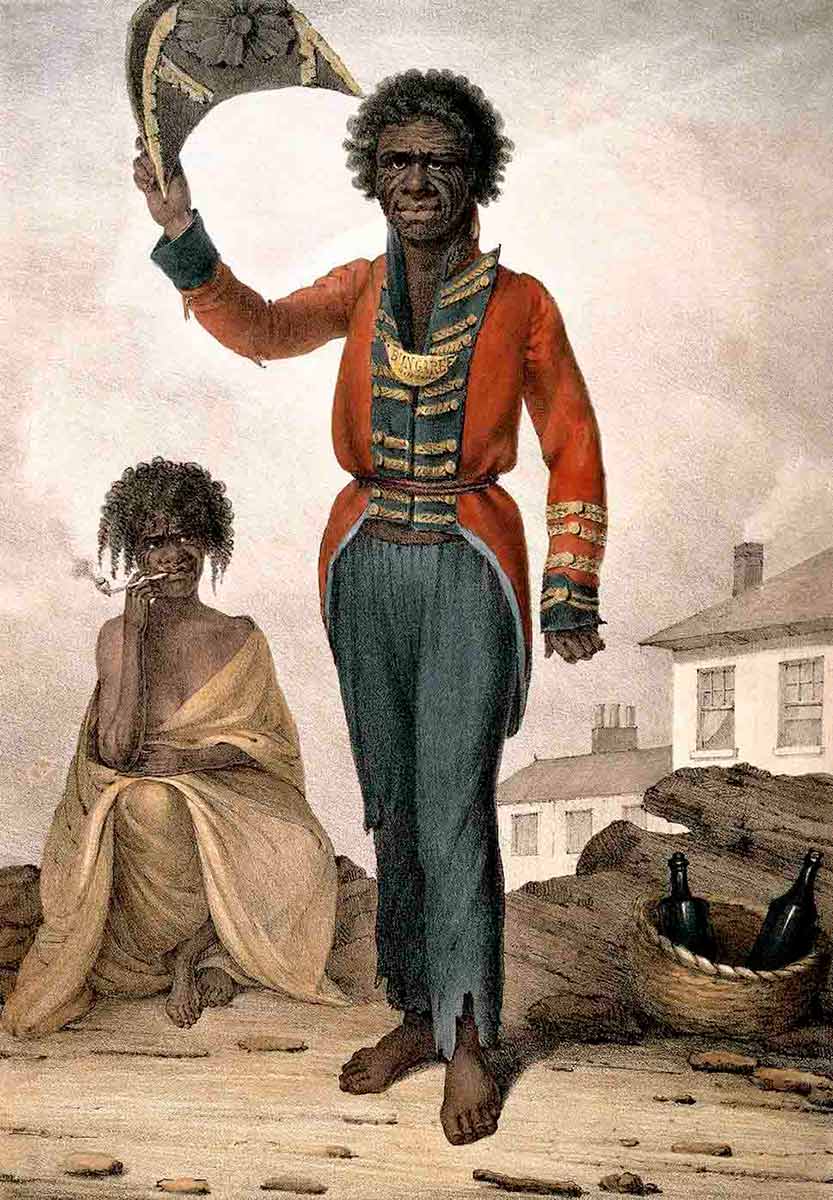

Breastplates, also known as gorgets and king plates, were issued to Aboriginal elders and other people including stockmen, trackers and individuals for reasons including faithful service and saving the lives of non-Indigenous people.

This breastplate records a cross-cultural encounter and the appreciation the expedition committee extended to the Yandruwandha people.

Burke and Wills

Burke and Wills led the Victorian Exploring Expedition in the hope of achieving the first south to north crossing of the Australian continent. They left Melbourne in August 1860 but Burke found the expedition's progress frustratingly slow and feared that rival explorer John McDouall Stuart might reach the Gulf of Carpentaria first.

In the race to reach their northern destination, Burke pushed ahead and left Cooper Creek in December 1860 with Wills, John King, Charley Gray, six camels and Burke's horse Billy. Four men with some camels and horses remained at Camp 65 at Cooper Creek.

Burke and Wills reached a tidal channel but were unable to get through to the ocean. However, they had reached their goal.

Living off the land

Burke's Gulf party had eaten two-thirds of their food on the way north. Bad weather delayed their return and the men began eating the animals as they grew weaker. Gray died on 17 April 1861.

A few days later Burke, Wills and King arrived back at Camp 65, exhausted, almost starving and hardly able to walk. They were expecting help and a rousing welcome but the camp was deserted. The rest of the party had given up and had left only hours before.

The explorers did not know how to live off the land. When their supplies ran out they were given fish and nardoo (aquatic fern) by the Yandruwandha. After their benefactors moved on, the explorers existed on nardoo alone. It made them feel full but was actually poisoning them. Burke and Wills both died on the banks of the Cooper.

After their deaths, the Yandruwandha cared for King and alerted Alfred Howitt's relief party on 15 September 1861. King returned to Melbourne, the only survivor of the party that set out from Cooper Creek for the Gulf.

Presentation to the Yandruwandha

The Victorian Exploration Committee, which oversaw arrangements for the Burke and Wills expedition, had three breastplates produced.

The Records of the Royal Society of Victoria's Exploration Committee, the Victoria Exploring Expedition and Relief Expeditions, 1857–73, held by the State Library of Victoria state that these plates were to be 'presented to the tribes that had succoured the lamented Explorers Messrs Burke & Wills and the survivor King'.

The plates were engraved by Melbourne artisan Xavier Arnoldi at a cost of £1.5.0 each. In 1862, Howitt returned to Cooper Creek to gather the remains of Burke and Wills for burial in Melbourne. It was on this second trip that he presented the breastplates, especially commissioned by a grateful Victorian Exploration Committee.

The inscription on the front of the plate states that it was presented, 'for the Humanity shewn to the Explorers Burke, Wills and King 1861'.

In dispatches sent by members of the Victorian Relief Expedition to the Exploration Committee, also held by the State Library of Victoria, Howitt reported:

Sir, I have the honour to report my arrival at this place with the V.E. Party − all well − bringing down the remains of the late explorers Burke and Wills ... Before leaving for the settlements I also collected the natives of our part of the creek and informing them that we were now returning to our own country, gave them clothes and other presents that I had [provided?], and also the p [letter p crossed out,] brass plates furnished for that purpose by the Committee.

The National Museum of Australia bought the Victorian Exploring Expedition breastplate at auction in 2009. A second plate is held by the South Australian Museum. The whereabouts of the third is unknown.

The crescent-shaped plate is 207 millimetres long and 93 millimetres high and weighs 150.2 grams. Closer examination revealed it was cut from a larger sheet of metal, with bevelled edges and holes for attaching a chain or string.

The reverse shows marks from a hammer, used to induce a bend in the plate during its manufacture. The plate shows little evidence of use, with no wear marks on the surface or hanging points.

Many of the breastplates in the Museum's collection feature the names of their recipient. The Victorian Exploration Expedition plate has been left blank. Senior curator David Kaus notes that leaving the name off plates is highly unusual, but was probably the case because Howitt was unsure to whom they should be presented.

The breastplate is one of several objects related to the Burke and Wills expedition now held by the National Museum.

History of breastplates

Historically, gorgets were part of the suit of armour worn by medieval knights over the throat. They were adapted for battle in various fields but later became more decorative and were worn for ceremonial purposes.

Early Aboriginal breastplates were modelled on gorgets worn as badges by infantry officers in Australia until 1832. They were given to Aboriginal people from 1815 to 1946.

Throughout their history, breastplates remained crescent-shaped with only rare exceptions.

Not all breastplates featured decoration additional to the inscription, but there was considerable variety in the engraved designs of those plates that were decorated.

Many of the early Australian breastplates were engraved using the same conventions that applied to European heraldry, particularly coats of arms.

Some breastplates feature kangaroos and emus, for example, with their heads turned looking over their shoulders − a common heraldic feature known as 'regardant'.

Kangaroos and emus are by far the most common motifs. Other Australian animals found on breastplates include platypuses, lyrebirds, lizards and snakes. Grass and grasstrees are the most common plants to be found. Other common motifs include Aboriginal people, sprigs, weapons and coronets.

By 1946, when the last known breastplate was presented in Australia, hundreds, if not thousands, had been handed out. They were presented for a range of reasons, including as rewards for saving the lives of non-Indigenous people, for faithful service and to recognise stockmen and trackers.

In our collection