This canoe belonged to environmental campaigner Val Plumwood. She survived a crocodile attack while canoeing alone in Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory in 1985. Plumwood was inspired to explore philosophical ideas about death in an ecological context.

Environmental philosophy

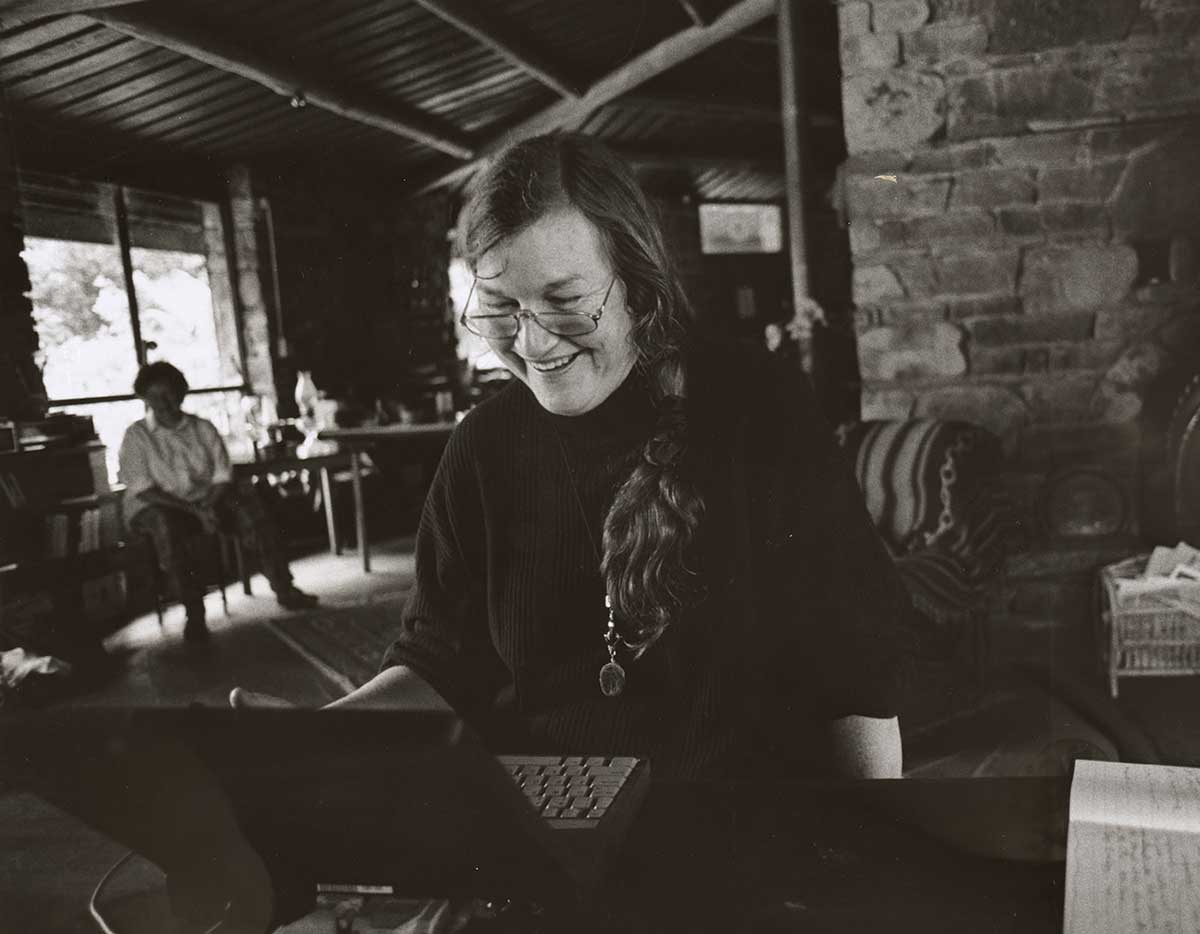

Val Plumwood was an eminent Australian environmental philosopher. From the 1970s until her death in 2008, Plumwood worked to expose problematic attitudes towards the natural world that she identified within Western culture and thought.

In her scholarly work Plumwood analysed how Western understandings of an opposition between human reason and the natural world were both historically constructed and applied with devastating consequences.

Her knowledge of natural systems deepened through decades of close engagement with the vibrant rainforest biota of Plumwood Mountain, where she lived in southern New South Wales, and from which she took her name.

The terrifying experience of surviving a crocodile attack while canoeing alone in Kakadu National Park in the Top End of the Northern Territory in 1985 inspired Plumwood to explore philosophical ideas about death within an ecological context.

In 2012 the Museum acquired the five-metre-long canoe that Plumwood was paddling when the crocodile attack began.

Kakadu National Park

In the 1960s the Northern Territory Government established the Alligator Rivers Wildlife Sanctuary. The reserve included most of the area that became Kakadu National Park in 1979.

Before the establishment of the national park, the Northern Territory government constructed three wildlife ranger stations inside the sanctuary.

Greg Miles began working as a ranger in the Kakadu area in 1976. He lived at Cannon Hill, one of the three original ranger stations, and where the Northern Territory government supplied a canoe.

Miles often used the canoe to cross local waterways. When he moved from Cannon Hill to the new East Alligator ranger station in 1979, he took the canoe with him.

Crocodile attack

In 1985 Val Plumwood visited Kakadu. As an activist, she’d fought to protect the Kakadu area and to secure its status as a national park. Towards the end of her stay, Plumwood camped at the East Alligator ranger station where Greg Miles was planning a new walking trail.

Miles knew that Plumwood was an experienced long distance bushwalker, and asked her to walk the proposed route and provide feedback. Miles explained that he hoped she might 'comment on attractiveness, ease of walking, clarity of the alignment and anything else she might find notable’.

The trail departed from a tributary of the East Alligator River near the station. Miles lent Plumwood the canoe so that she could paddle across the tributary, then walk along the trail.

Although the saltwater crocodile population had substantially recovered since the banning of hunting a decade previously, canoeing amongst them was not considered risky. Throughout the region, government agencies commonly issued canoes for staff to undertake official duties.

Unbeknownst to Plumwood and Miles, heavy rainfall upriver had begun to swell the East Alligator and the river was soon to flood. Light rain had started to fall as Plumwood paddled away from the canoe launch point on the tributary.

The rising water obscured landmarks, she couldn’t locate the trailhead, and the rain got heavier. In ‘Being prey’, a landmark scholarly article published in 1996, Plumwood wrote about the dramatic events that unfolded:

When I pulled my canoe over in driving rain to a rock outcrop rising out of the swamp for a hasty, sodden lunch, I experienced the unfamiliar sensation of being watched. Having never been one for timidity, in philosophy or in life, I decided, rather than return defeated to my sticky caravan, to explore a clear, deep channel closer to the river I had travelled along the previous day.

After exploring the channel, and with a growing sense of unease, Plumwood decided to return to her caravan at the East Alligator station:

As I pulled the canoe out into the main current, the torrential rain and wind started up again; the swelling stream would carry me home the quicker, I thought. I had not gone more than five or ten minutes back down the channel when, rounding a bend, I saw ahead of me in midstream what looked like a floating stick − one I did not recall passing on my way up. As the current moved me toward it, the stick appeared to develop eyes. A crocodile! It is hard to estimate size from the small nose and eye protrusions the crocodile leaves, in cryptic mode, above the waterline, but it did not look like a large one. I was close to it now but was not especially afraid; an encounter would add interest to the day.

Although I was paddling to miss the crocodile, our paths were strangely convergent. I knew it was going to be close but was totally unprepared for the great blow that came against the side of the canoe. Again it came, again and again, now from behind, shuddering the flimsy craft. I paddled furiously, but the blows continued. The unheard of was happening; the canoe was under attack, the crocodile in full pursuit! For the first time, it came to me fully that I was prey. I realized I had to get out of the canoe or risk being capsized or pulled into the deeper water of mid channel.

Plumwood tried to leap into the lower branches of a nearby paperbark tree. As she leapt from the canoe, the crocodile burst from the water and dragged her down and into a terrifying ‘death roll’:

Few of those who have experienced the crocodile’s death roll have lived to describe it. It is, essentially, an experience beyond words of total terror, total helplessness, total certainty, experienced with undivided mind and body, of a terrible death in the swirling depths. The crocodile’s breathing and heart metabolism is not suited to prolonged struggle, so the roll is an intense initial burst of power designed to overcome the surprised victim’s resistance quickly. Then it is merely a question of holding the now feebly struggling prey under the water a while for an easy finish to the drowning job. The roll was a centrifuge of whirling, boiling blackness, which seemed about to tear my limbs from my body, driving water into my bursting lungs. It lasted for an eternity, beyond endurance, but when I seemed all but finished, the rolling suddenly stopped. My feet touched bottom, my head broke the surface, and spluttering, coughing, I sucked at air, amazed to find myself still alive. The crocodile still had me in its pincer grip between the legs, and the water came just up to my chest. As we rested together, I had just begun to weep for the prospects of my mangled body when the crocodile pitched me suddenly into a second death roll.

When the tearing, whirling terror stopped again (this time perhaps it had not lasted quite so long), I surfaced again, still in the crocodile’s grip, next to the stout branch of a large sandpaper fig growing in the water. I reached out and held onto the branch with all my strength, vowing to let the crocodile tear me apart rather than throw me again into that spinning, suffocating hell. For the first time I became aware of a low growling sound issuing from the crocodile’s throat, as if it were angry. I braced myself against the branch ready for another roll, but after a short time the crocodile’s jaws simply relaxed. I was free. With all of my power, I used my grip on the branch to pull away, dodging around the back of the fig tree to avoid the forbidding mud bank, and tried once more the only apparent avenue of escape, to climb into the paperbark tree.

As in the repetition of a nightmare, when the dreamer is stuck fast in some monstrous pattern of destruction impervious to will or endeavor, the horror of my first escape attempt was exactly repeated. As I leapt into the same branch, the crocodile again propelled itself from the water, seizing me once more, this time around the upper left thigh. I briefly felt a hot sensation before being again submerged in the terror of the third death roll. Like the others, it stopped eventually, and we came up in the same place as before, next to the sandpaper fig branch. I was growing weaker, but I could see the crocodile taking a long time to kill me this way. It seemed to be intent on tearing me apart slowly, playing with me like a huge growling cat with a torn mouse. I did not imagine that I would survive, so great seemed its anger and its power compared to mine. I prayed for a quick finish and decided to provoke it by attacking it with my free hands. Feeling back behind me along the head, I encountered two lumps. Thinking I had the eye sockets, I jabbed my thumbs into them with all my might. They slid into warm, unresisting holes (which may have been the ears or perhaps the nostrils), and the crocodile did not so much as flinch. In despair, I resumed my grasp on the branch, dreading death by slow torture. And once again, after a time, I felt the crocodile jaws relax, and I pulled free.I knew now that I must break the pattern. Not back into the paperbark. Up the impossible, slippery mud bank was the only way. I threw myself at it with all of my failing strength, scrabbling with my hands for a grip, failing, sliding, falling back to the bottom, to the waiting jaws of the crocodile. I tried a second time and almost made it before sliding back, braking my slide two-thirds of the way down by grabbing a tuft of grass. I hung there, exhausted, defeated. I can’t make it, I thought. It’ll just have to come and get me. It seemed a shame, somehow, after all I had been through. The grass tuft began to give way. Flailing wildly to stop myself from sliding farther, I found my fingers jamming into the soft mud, and that supported me. This was the clue I needed to survive. With the last of my strength, I climbed up the bank, pushing my fingers into the mud to hold my weight, reached the top, and stood up, incredulous. I was alive!

With severe injuries, Val Plumwood began walking towards the ranger station, some kilometres away on the other side of the river. When she didn’t return to the station by nightfall, Greg Miles led a search party that eventually found her.

Unfortunately, Plumwood’s ordeal was far from over. Roads were flooded and the swollen waterways were almost impossible to navigate by boat. With help from other park staff, Miles and his wife embarked on a perilous voyage from East Alligator to meet an ambulance rushing south from Darwin.

Canoe retrieved

James Wauchope, an Aboriginal ranger based at East Alligator who was instrumental in rescuing Plumwood, retrieved the canoe from the backwaters of the East Alligator River a day or two after the rescue, somewhere along the tributary near where the philosopher was found.

Ranger Paul Cawood recalled that Wauchope was ‘a real bushman’, an experienced buffalo and crocodile shooter, who knew the area intimately.

After the crocodile attack, park management recalled all canoes for storage at the ‘dry dump’ at the headquarters of Kakadu National Park, near Jabiru.

Andrew and Hilary Skeat, who donated the canoe to the Museum in 2012 explained that when the canoe paddled by Val Plumwood was in storage at the dump someone, perhaps a park employee, used a crowbar to punch holes through its floor and side, thereby draining it of rainwater that had accumulated inside and where mosquitoes were breeding.

Andrew Skeat was working as a biologist at park headquarters at the time of the attack, while his wife Hilary was employed as an executive officer at the Alligator Rivers Region Research Institute.

Andrew and Hilary lived with their small children adjacent to park headquarters. In time, after the canoe had deteriorated in condition and was, for all purposes, abandoned by park management, Andrew rescued it from the dry dump for his children to use as play equipment.

In 1992 the Skeat family left Kakadu and settled on Magnetic Island, near Townsville in northern Queensland. They took the canoe with them and repaired it sufficiently for the family to explore the island’s beaches and reefs. Andrew made a detachable outrigger to make the craft more stable.

While the canoe paddled by Val Plumwood in the floodwaters of the East Alligator River is almost five metres long, when imagined in relation to the powerful natural forces of the Kakadu region, its fibreglass and plywood seem fragile indeed.

The image of a lone figure, drifting in rain through unfamiliar country, on rising waterways, in a region where saltwater crocodiles were increasing in number and collective power, evokes an intense sense of vulnerability.

In her later work, Plumwood emphasised the vulnerability of modern, industrial society to the forceful effects of anthropogenic climate change and ecological degradation − a vulnerability produced by a widespread cultural failure to understand human dependence on dynamic and life-giving systems of nature.

Interpreting the attack

In her 1996 paper ‘Being Prey’, Val Plumwood interpreted the crocodile attack in terms of the significant body of environmental philosophy that she’d developed over decades:

[B]efore the event, I saw the whole universe as framed by my own narrative, as though the two were joined perfectly and seamlessly together. As my own narrative and the larger story in which it was embedded were ripped painfully apart, I glimpsed beyond my own realm a shockingly indifferent world of necessity in which I had no more significance than any other edible being. The thought, ‘This can’t be happening to me, I’m a human being not meat, I don’t deserve this fate!’ was one component of my terminal incredulity. Confronting the brute fact of being prey, together with the astonishing view of this larger story in which my ‘normal’ ethical terms of struggle seemed absent or meaningless, brought home to me rather sharply that we inhabit not only an ethical order, but also something not reducible to it, an ecological order. We live by illusion if we believe we can shape our lives, or those of the other beings with whom we share the ecosystem, in the terms of the ethical and cultural sphere alone.

In Living On, a film produced four years before her death, Plumwood spoke about the subtle yet profound effect of the terrifying event at Kakadu on her scholarly thinking:

My work really changed course afterwards. I didn’t see it for quite some time. But it really started to emphasise the power of nature, and why we weren’t aware of the power of nature, and being deluded about that power. So I write a lot about that now. And I think this has got a lot to do with why we don’t take account of the environmental crisis. We have this illusory sense of invulnerability. We don’t understand ourselves as ecological beings. We don’t understand ourselves as embedded in an ecosystem. Because we think we are so totally special and apart. Everything else is food for us, but we’re not food for anything else. I think the message was that this is an illusion and that we are food like everything else.

Despite the powerful influence of the near death encounter, Val Plumwood refused to be defined only in relation to the attack and her survival:

I don’t want my life to be reduced to that event, but it was certainly an important event, in terms of shaping the way I think about the world, and what I do in the world. Yes, some people call me ‘the crocodile woman’, as if this is one of the defining events in my life, and I don’t see it that way of course. I’ve written some quite important books, so I get quite annoyed by people who refer to me as ‘the crocodile woman’.

'Part of the feast': The life and work of Val Plumwood, a celebration of Val's life and legacy was recorded at the National Museum on 7 May 2013. The forum featured ABC broadcaster Gregg Borschmann, anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose, editor Lorraine Shannon, curator George Main and crocodile expert Grahame Webb.

In our collection

References

Freya Mathews, ‘Val Plumwood’, obituary, The Guardian, 26 March 2008.

Val Plumwood, Feminism and the Mastery of Nature, Routledge, London, 1993.

Val Plumwood, ‘Being prey’, Terra Nova, vol. 1, no. 3, 1996.

Val Plumwood, Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason, Routledge, New York, 2001.

Richard Routley and Val Routley, The Fight for the Forests: The Takeover of Australian Forests for Pines, Wood Chips and Intensive Forestry, Australian National University, Canberra, 1973.