Children’s toys and costumes from the National Museum’s collection reveal connections with popular culture, globalisation and the re-evaluation of colonial history.

Cowboys, cowgirls and Indians

If the National Historical Collection is anything to go by, ‘Cowboys and Indians’ was an extraordinarily popular children’s game between the 1920s and 1980s. The Museum’s many costumes and toys are remarkable for their distinctive transnational design.

Through the rosy lens of nostalgia, the so-called ‘Wild West’ appears to be all in good fun. Similar rough-and-tumble duels certainly continue to captivate children today. But do these objects hold deeper cultural meanings in a postcolonial world?

In recent years, global advocacy for reconciliation has implicated the game and its stereotypical costumes in reappraisals of colonial history. But whether this material culture represents cultural appropriation, a meeting of colonial and First Nations culture, or some new hybrid creation, is a question not easily answered.

Playing frontiers

Historian Ann McGrath has placed the game’s turn-of the-century beginnings at a key intersection of popular culture, colonialism and modernity. The Wild West genre is largely unrelated to any ‘real’ events in the 19th century colonisation of the American plains.

Instead, early and mid-20th century frontier games played across the world created a formulaic colonial myth involving land rights, cultural differences and violence. Without doubt, racial and colonial stereotypes were reinforced in Australian backyards and urban fringes – all unceded First Nations’ land.

But beyond the cliched plotlines, the act of playing provided generations of children with an unrivalled chance to experiment with the dynamics of power and identity.

Crazy for cowboys

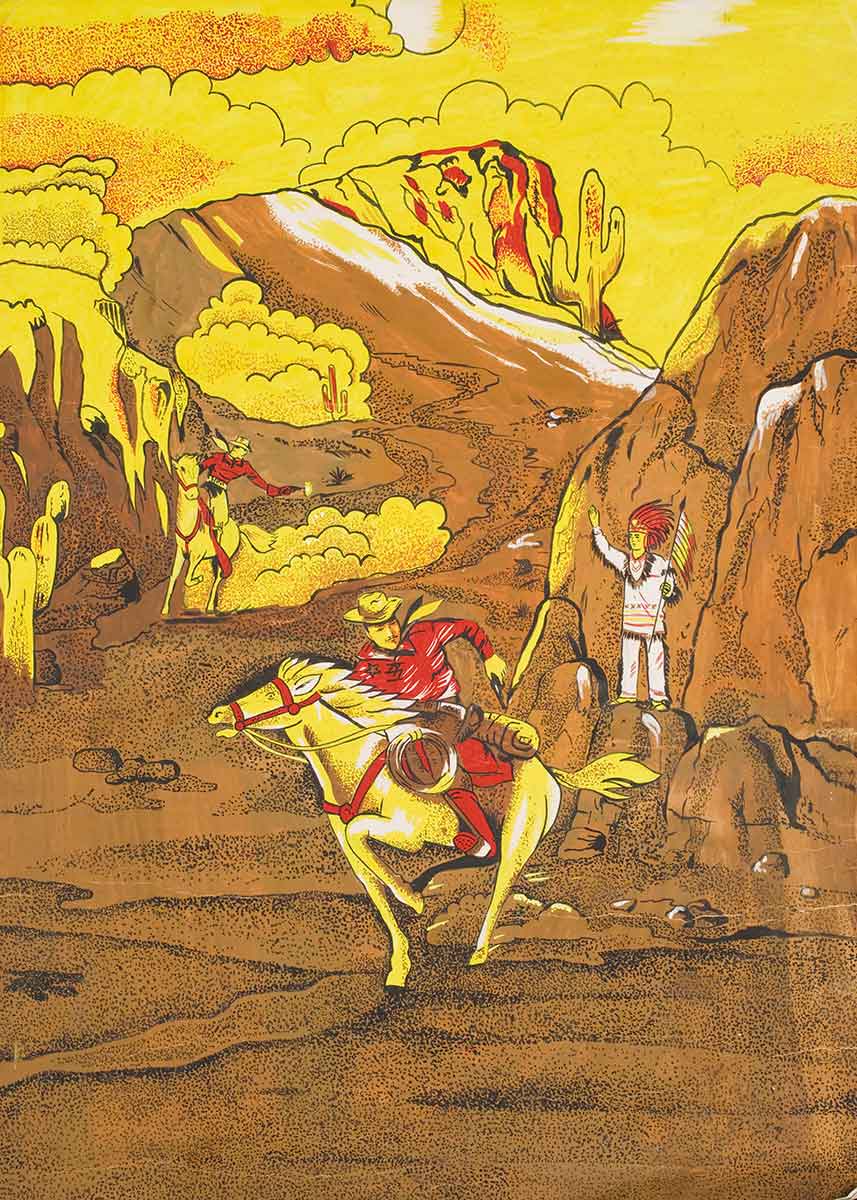

The Museum’s collection records how the myth of American colonisation was born in the entertainment industry at the beginning of the 20th century. The Wild West – featuring rocky hillsides, pistols, buckskin, horse-sweat, square-dancing and feathers – became an evolving global genre.

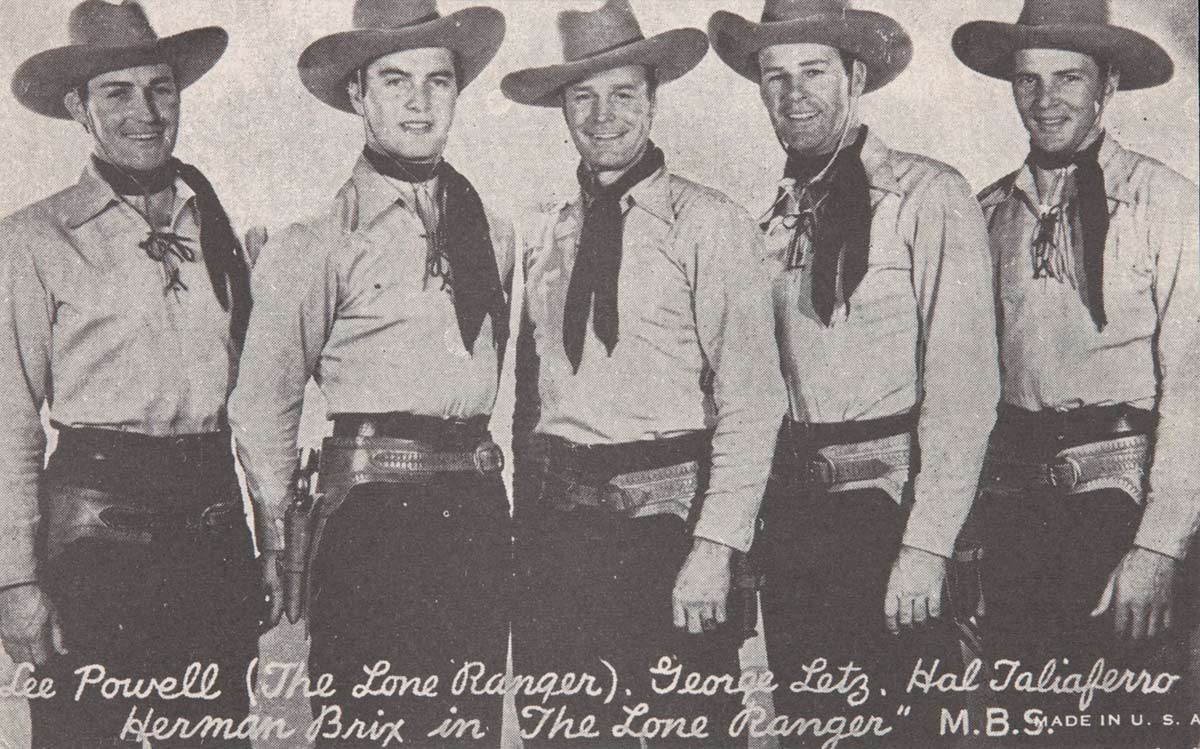

By the 1920s and 1930s comic books, radio serials, music and rodeo performances had taken up the theme with enthusiasm. Most popular were gritty Western movies and their stylish Hollywood actors.

By the early 1950s many Australian children were devotees. To one Brisbane journalist’s despair, ‘little boys swagger around in blue jeans, check shirts and cowboy hats … there is hardly a suburb where the unwary pedestrian can escape being ambushed in the best Hollywood style’.

Watching the market

Above all, it was the arrival of television in 1956 that affirmed the cowboy’s place in Australian popular culture. Western serials featured on the early evening program and were enjoyed by the whole family from the comfort of their loungerooms.

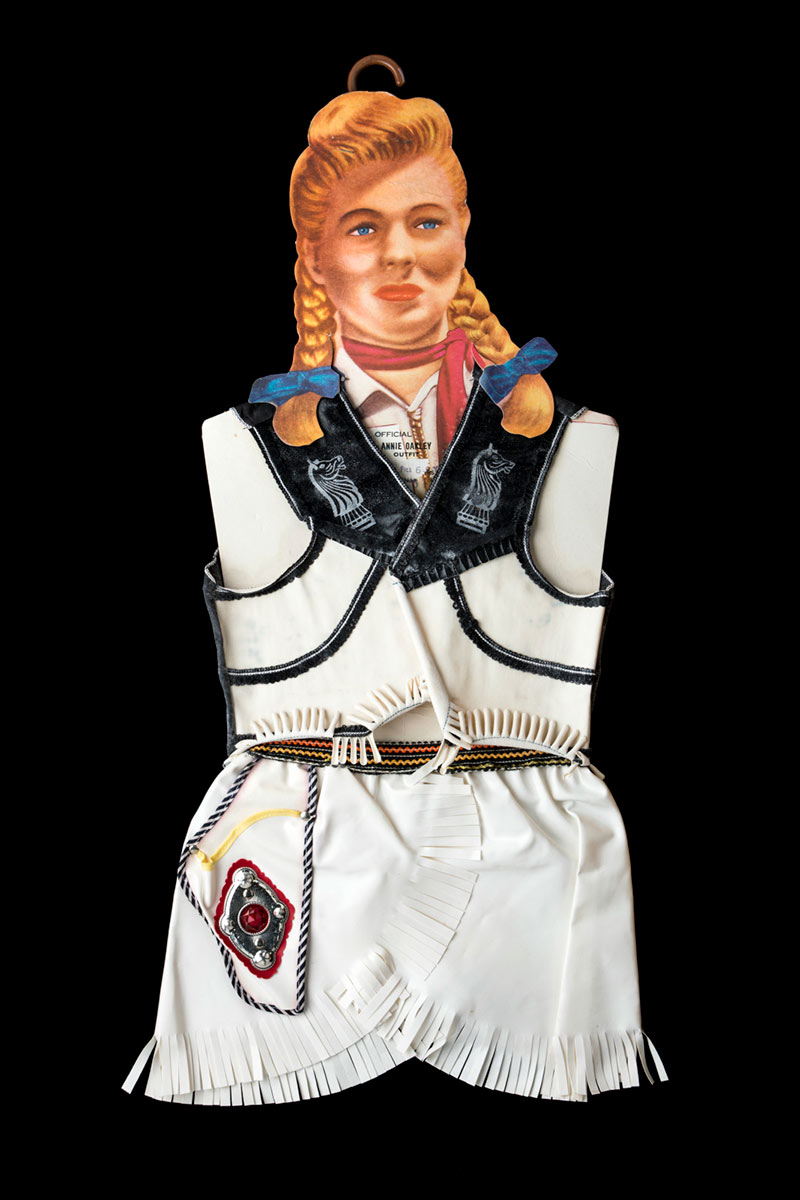

Prior to this, children’s costumes were mostly made by hand from fabric scraps or paper. Now cheap, shop-bought, western-style costumes were in hot demand.

Many Australian suppliers, including Lindsay’s toy factory in Sydney, stepped up to the challenge. Inspired by the games played by his children, Albert Lindsay first made cowboy costumes in the 1930s.

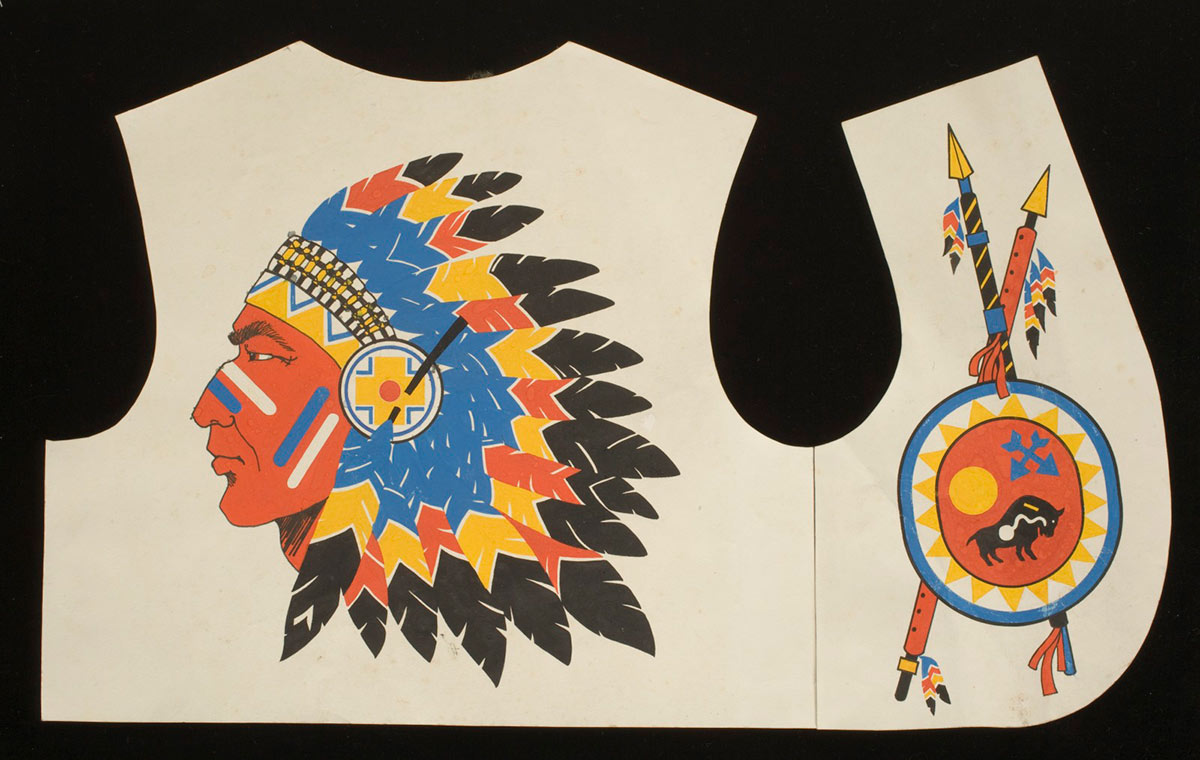

After 1956 Lindsay’s acquired licences from the major American production companies and created a range of dazzling characters drawing on the most popular television programs.

Wild and outside

Lindsay's costumes were functional clothing, not novelty outfits. Their generous cuts fit easily over everyday clothes and were free from fiddly zips and buttons. Elastic waistbands allowed freedom of movement or quick swaps as allegiances shifted across the bush and backyard.

Some players relished remaining in character all day. In 2005 donor John Coleman said:

I was 4 or 5 ... and that Christmas … I was given these black cowboy boots and, you know, we were in Sydney in summer. It was really hot and I insisted on wearing these cowboy boots whenever we walked around. My skinny legs in a pair of shorts and these cowboy boots with the stitching up, halfway up the sides.

Into the sunset

Australian children’s dedication to Cowboys and Indians waned some time during the 1980s. Alarm over gun-toting violence may be partly responsible, but other expanding genres of popular entertainment hastened its demise.

Most relevant are the global calls by First Nations peoples for recognition of frontier violence and cultural appropriation. Sociologist Michael Yellow Bird views the game as perpetuating America’s ‘past and present infatuation with colonization and genocide’. Some groups have recently abandoned the use of pejorative Native American symbols or names.

In Australia, the cowboy lives on in the ranching identity of First Nations cattle industry workers. Their adoption of the material culture of Cowboys and Indians as a symbol of resistance and empowerment marks yet another chapter in the game’s complex and evolving legacy.

Explore more Play

You may also like