Necklace-making is the most significant cultural tradition of Tasmanian Aboriginal women.

It is also one of the few traditions that have continued without interruption since before the European colonisation of Tasmania (formerly Van Diemen's Land) in 1803.

Whereas colonisation disrupted or destroyed so much of Tasmanian Aboriginal life and heritage, necklace-making has not only continued but evolved.

This collection consists of two Tasmanian Aboriginal shell necklaces.

One is a strand of pearly green maireener (rainbow kelp) shells, brown rice shells and black cats' teeth shells. The other is a strand of pearly blue-green maireeners, brown and white rice shells and pink button shells.

Unbroken tradition

The knowledge and skills of shell processing and stringing has been passed down through generations of women, particularly the women of the Furneaux Islands, off Tasmania’s north-east coast.

Necklace-making is an opportunity for women of all ages to get together and share stories, pass knowledge to younger generations and continue to affirm their culture.

These necklaces were made by Aunty Dulcie Greeno, an elder of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. She was born in 1923 on Cape Barren Island, one of the Furneaux Islands group.

She lived for many years on nearby Flinders Island, where she and her family continued the Aboriginal traditions of mutton-birding and crayfishing, and now lives in Launceston.

Aunty Dulcie has been making necklaces for more than 40 years, but first began practising as a child. ‘My grandmother used to do shell necklaces and a couple of my aunties,' she said in an interview for Australian Museums and Galleries Online. ‘We’d go round with them on the beach and collect shells with them.’

Now her sister (Corrie Fullard), daughter (Betty Grace), daughter-in-law, (Lola Greeno) and niece (Jeanette James) – all celebrated artists in their own right – make necklaces. Indeed, six of the eight necklaces currently in the Museum’s collections were made by Aunty Dulcie and members of her family.

Treasures through time

Shell necklaces were originally made as an adornment, as gifts and tokens of honour, and as objects to be traded with other sea and land peoples for tools or for ochre used in important ceremonies. Archaeologist Rhys Jones found a cremation within a cultural living place dating back at least 2000 years containing shells that had been pierced for a necklace.

After European colonisation, necklaces were also sold or exchanged for food, clothing and other essential supplies. Now, the artists are often commissioned to create necklaces for museums, galleries and private collectors.

Early European explorers remarked on the beauty of these treasures, and the esteem in which they were held. The French naturalist Jacques Labillardière, travelling with the d'Entrecasteaux expedition of 1791–94, observed women wearing 'strings of brilliant pearly blue spiral shells upon their bare heads'.

In 1802 his countryman Jean-Baptiste Leschenault de la Tour, botanist on the Baudin expedition of 1800–04, was given a necklace 'of small shells of glistening mother-of-pearl, threaded on a small cord made of bark and grass' by a man from Bruny Island whom Leschenault thought was a chief.

The Baudin expedition artists Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas Petit both drew shell necklaces. Petit's portrait of Baraourou, a young man from Maria Island, shows him wearing a tight necklet.

Other 18th- and 19th-century images show Tasmanian Aboriginal people wearing necklaces, including a photograph taken around 1866 of the leader and spokeswoman Truganini, who also made necklaces.

Painstaking process

Shell-stringing was (and remains) a painstaking process, requiring knowledge of coastal resources as well as great skill and patience.

Aunty Dulcie's daughter, Patsy Cameron, has explained how the women pierced each shell with a tool made from a jawbone and sharpened lower incisor of a kangaroo or wallaby.

The shells were then threaded on kangaroo tail sinews or on string made from natural fibres, smoked over a fire, and rubbed in grass to remove their outer coating and reveal the pearly surface. The shells were later polished with penguin or muttonbird oil.

European colonisation introduced new tools and materials, including acids such as vinegar to clean the shells and steel punches to hole them. Needles and cotton or synthetic thread enabled the women to incorporate smaller shells into increasingly intricate designs.

Some of Aunty Dulcie's necklaces use as many as 1700 shells, including rice shells so small they can fit under a fingernail. 'I like stringing these small rice shells', she said. 'The smaller the shells the daintier I think the strings are.'

Necklace-making is dependent on the availability of shells, and collecting remains a seasonal activity. Aunty Dulcie regularly returns to the Furneaux Islands to replenish her supplies. 'We still walk for miles on the beach', she said. 'We take our lunch and crawl along on our hands and knees to get the shells.'

Men often help women collect the shells, especially the maireeners (rainbow kelp shells), which live on kelp. These shells are best when picked directly from the sea. 'We don't use the ones we pick up on the beach because they are too brittle and they lose their colour,' said Aunty Dulcie.

Her father helped her grandmother and mother collect maireeners, but 'Dad always used to say [the rice shells] were too fiddly for him. He had such big hands.'

Adaptation and innovation

After colonisation, women started making longer necklaces. In 1835, Benjamin Duterrau sketched Tanleboneyer, 'a native of the district of Oyster Bay', and Bruny Island man Woorraddy, Truganini's husband, with long strands looped around their necks.

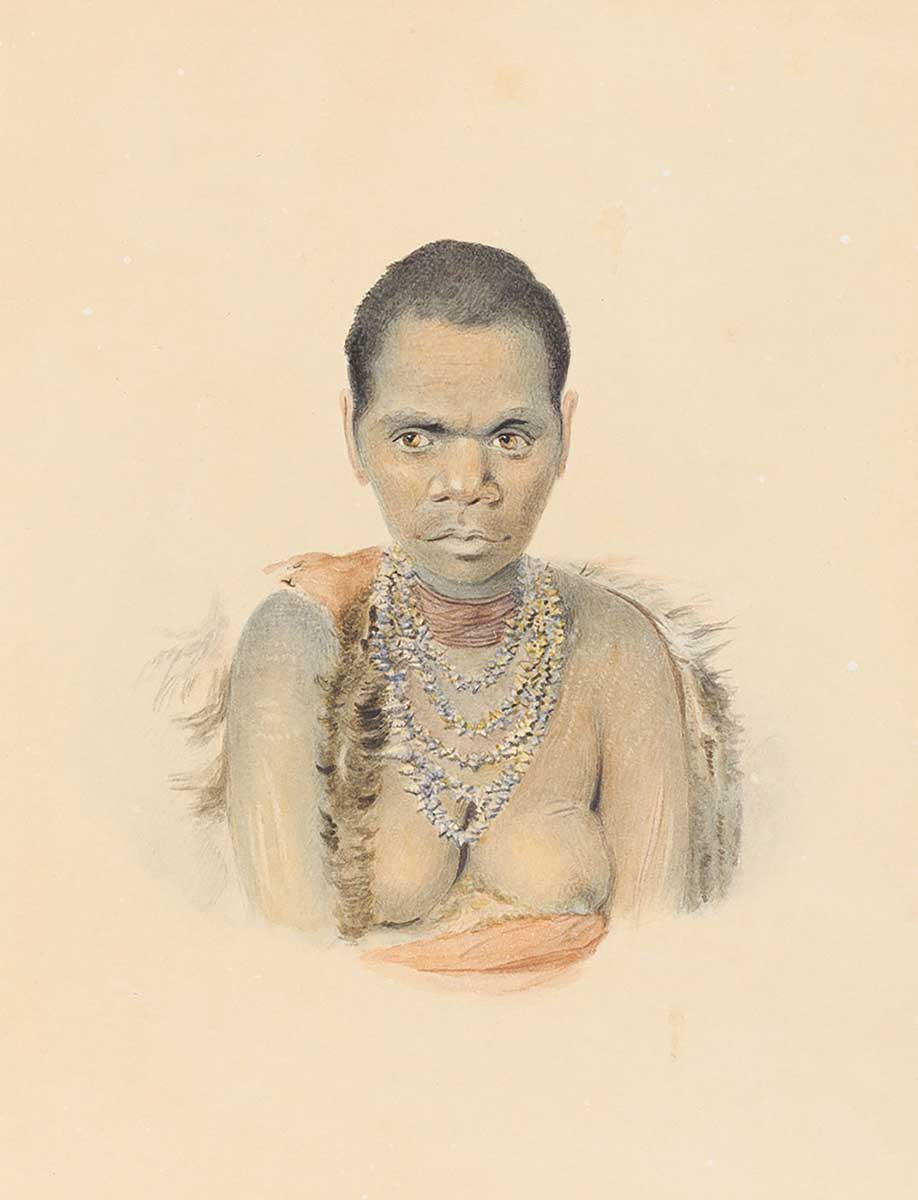

'Fanny' (whose name was Wortabowigee), a woman from Port Dalrymple featured in an 1837 portrait by Thomas Bock, wears five loops of what must have been a necklace of astonishing beauty.

It is possible that the new European tools adopted by the women led to this development, but it also indicates the changing circumstances of Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

Historian Brian Plomley points out that long necklaces would have been impractical to women accustomed to a traditional lifestyle of diving for crabs, crayfish and abalone, digging for root vegetables, hunting seals or climbing trees to catch possums.

Men tracking kangaroo, wallaby and emu through the bush would not have risked getting snagged by long necklaces – or risked damaging the valuable necklaces themselves.

The disruption of the traditional lifestyle of Tasmanian Aboriginal people after colonisation is reflected by the change in the necklaces. But this change also points to the Tasmanians' courageous assertion of their identity, and a continuation of their culture at a time when their world was being taken apart.

Iconic value

The connection of shell necklaces with the distinct culture and story of the Tasmanian Aboriginal people and with the Tasmanian natural environment means they have iconic status in the wider Tasmanian community. In 2009 they were listed as a Tasmanian Heritage Icon by the National Trust of Australia.

The cultural and aesthetic value of the necklaces is also demonstrated by their inclusion in many national and international museum, gallery and private collections. In Australia, Aunty Dulcie's necklaces have been exhibited widely.

As well as the National Museum of Australia, her work is in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia; the Australian National Maritime Museum; the National Gallery of Victoria; the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart; and the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston.

In our collection

You may also like