Aviation enthusiast Austin Byrne created a stunning memorial to the Southern Cross. Byrne spent more than 100,000 hours creating this tribute to the aircraft and its crew.

Austin Byrne, about 1985:

I well remember, as a young man, walking out to Mascot to watch the arrival of the Southern Cross – the first aeroplane to fly across the mighty Pacific Ocean from America to Australia.

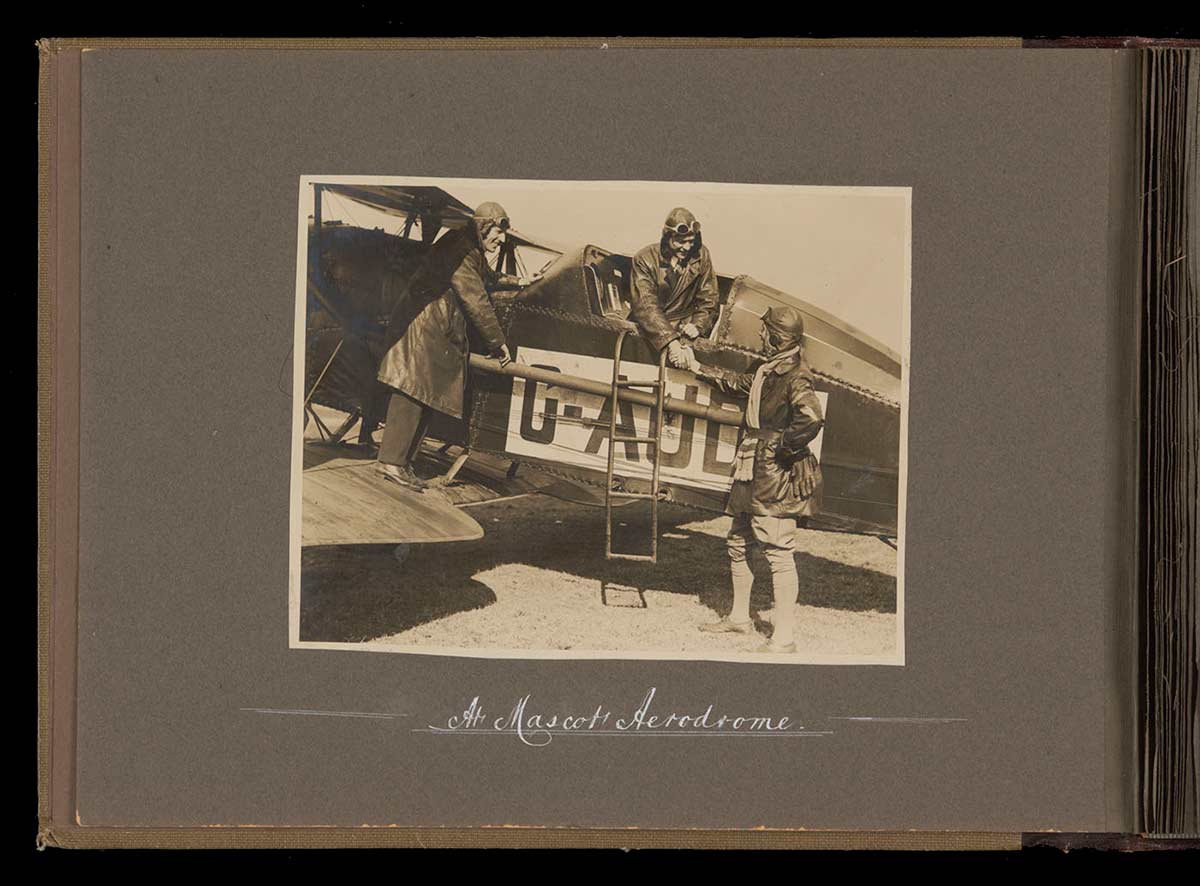

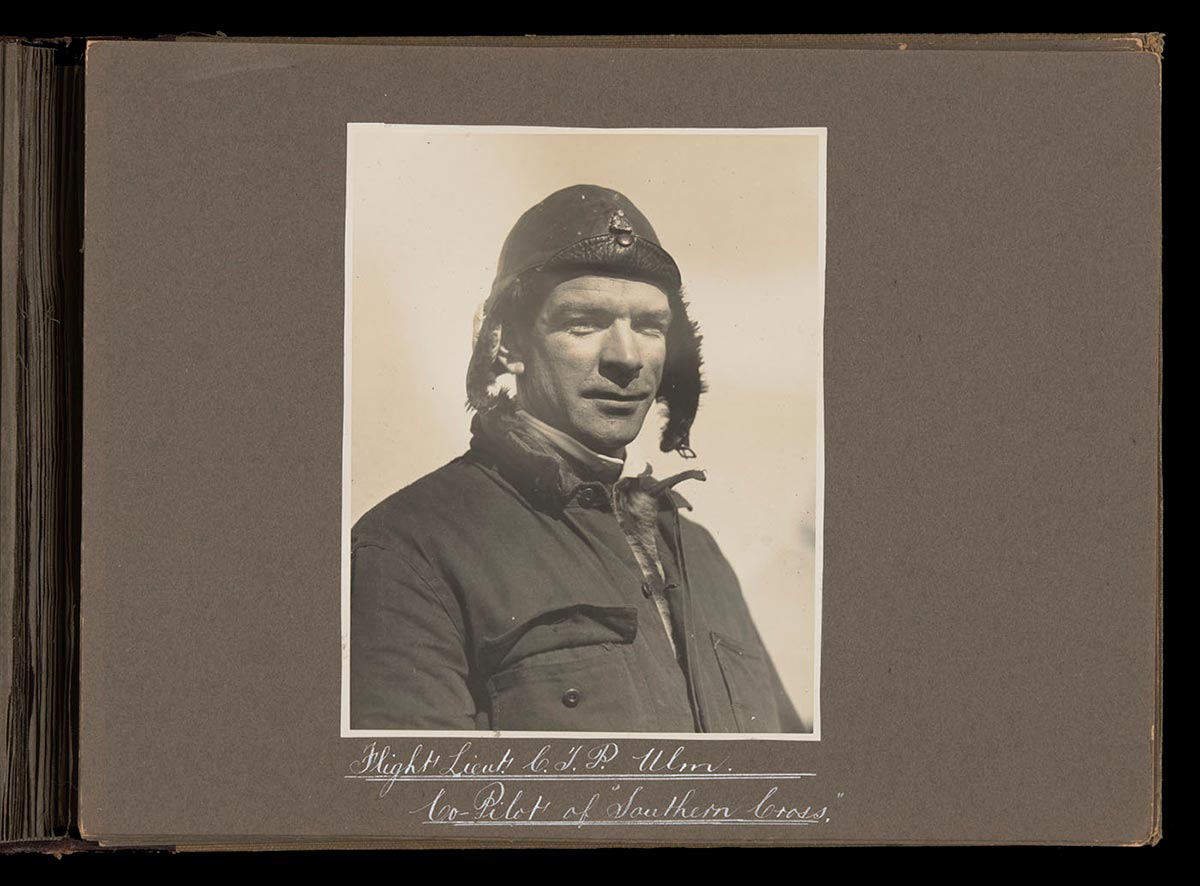

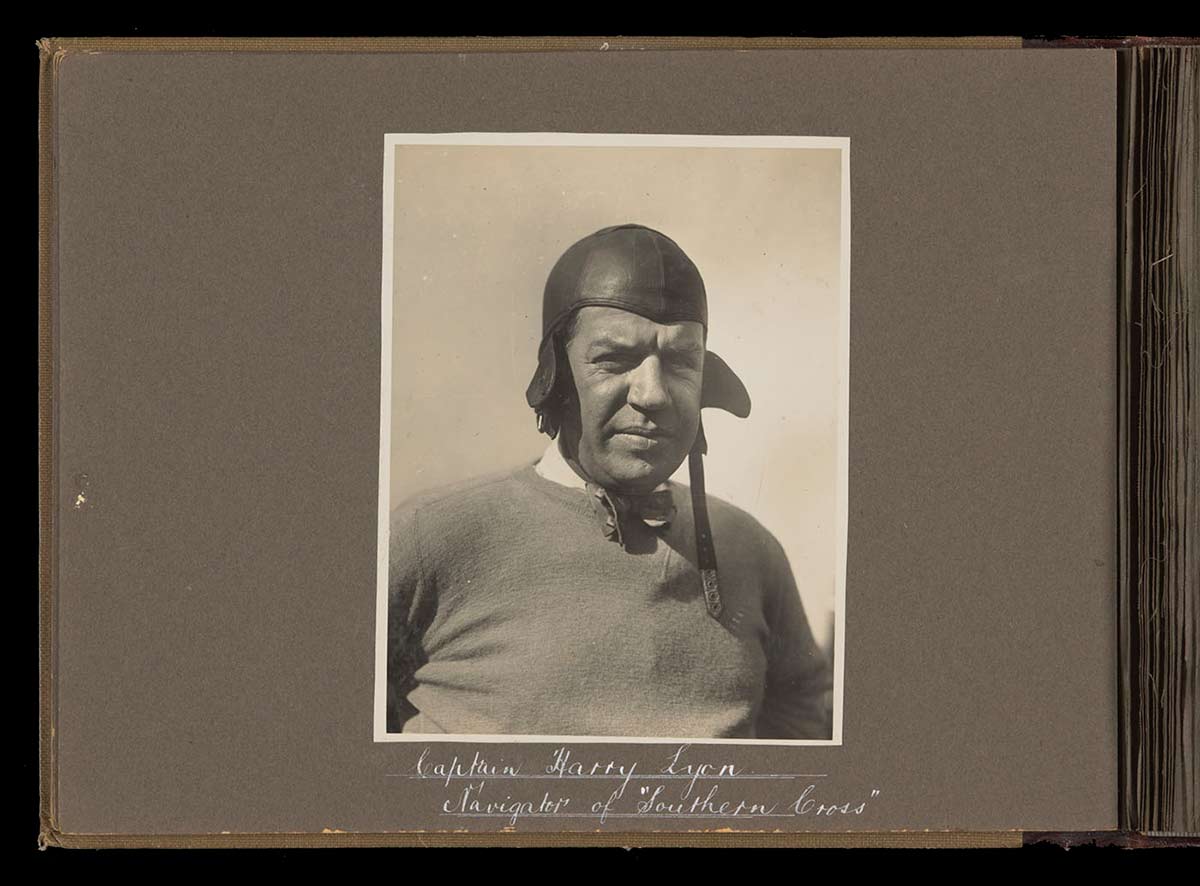

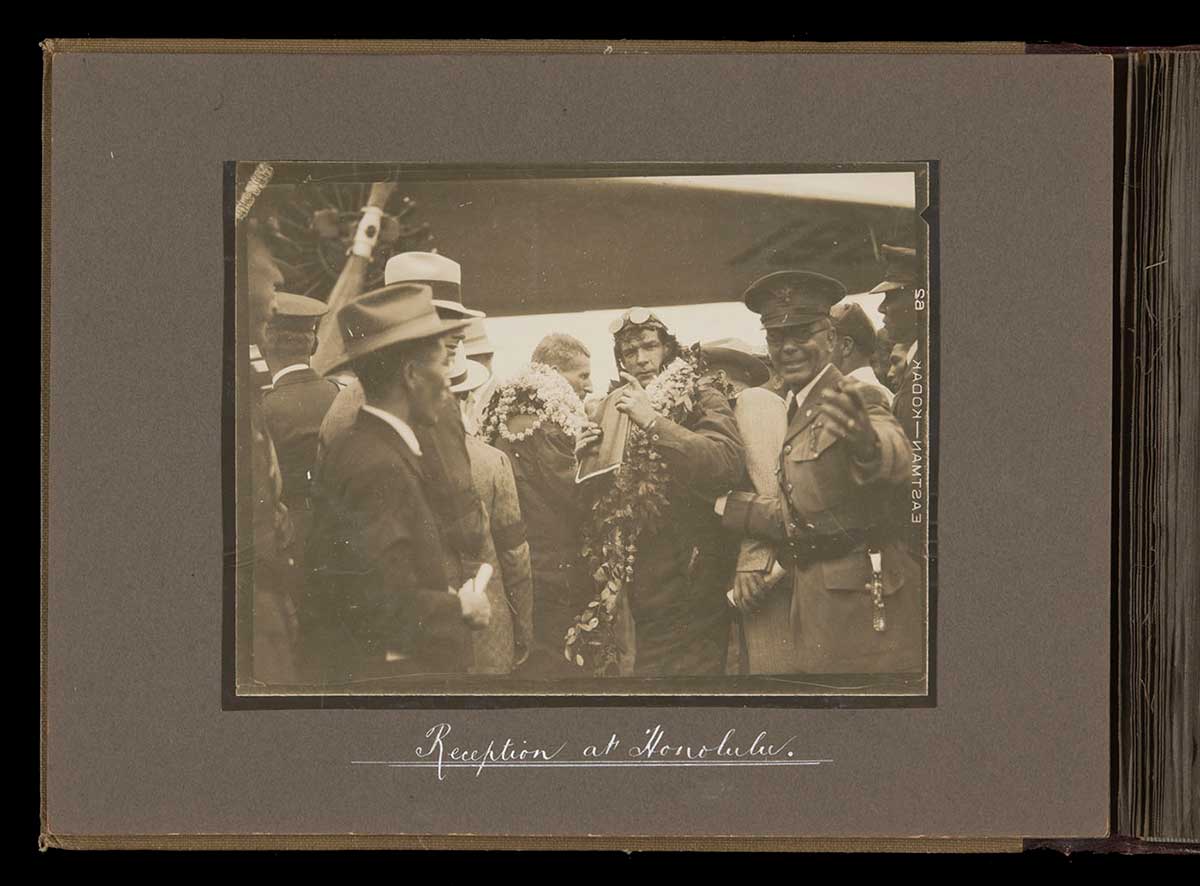

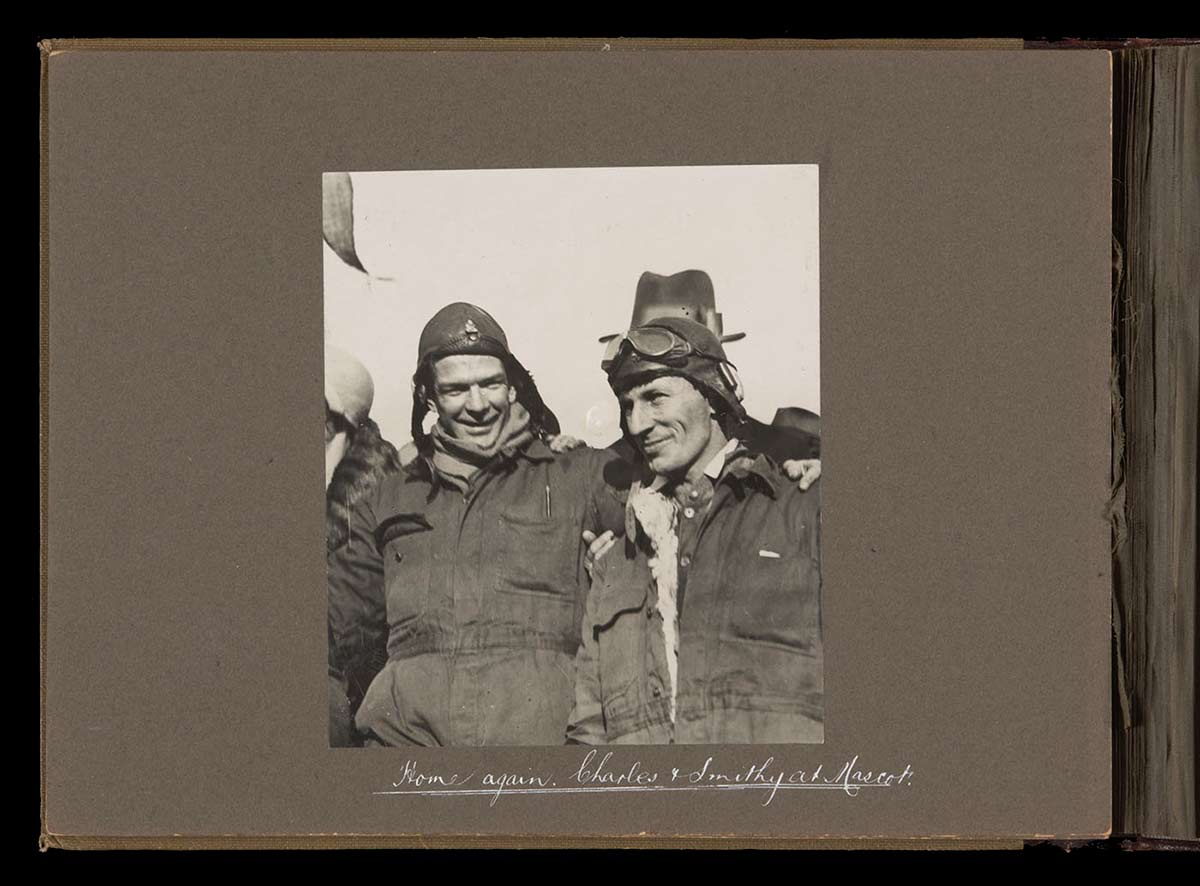

On 10 June 1928 Austin Byrne was part of the crowd of thousands that gathered at Mascot Aerodrome in Sydney to welcome the Southern Cross and its crew – Charles Kingsford Smith, Charles Ulm, Harry Lyon and James Warner – following their successful trans-Pacific flight.

After that event, Byrne was inspired to make a scale model of the Southern Cross. The model, however, marked only the beginning of Byrne’s construction efforts. By 1940 Byrne had created a Southern Cross memorial, and he dedicated the rest of his life to developing and touring his work.

Life-long passion

Austin Edward Byrne was born in 1902 at Newcastle, New South Wales. After his father died, Byrne's mother was unable to care for all her seven children, so in 1910 Byrne and his younger brother were sent to St Michael's Orphanage at Baulkham Hills.

Byrne later returned to the family home and left school in 1914 at the age of 12 to start working at the Cohen & Co store in Harden.

It was also in 1914 that Byrne first became interested in aviation when he saw French pilot Maurice Guillaux fly his Bleriot XI monoplane to deliver Australia's first airmail from Melbourne to Sydney.

In 1917 Byrne began working at the New South Wales Railways workshops as a labourer. Although he had little education, Byrne was an avid reader:

I read every book I could lay my hands on, especially those on the lives of the great artists. Michelangelo, what an inspiration he was!

Byrne's enthusiasm for aviation grew, and he followed the flights of Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm with interest. He recalled:

As a young man I was fascinated by man's conquest of the air. It presented limitless vision and thought for me. My heroes became Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm. I lived during and through that period of aerial pioneering. I lived with them, their trials, their heartbreaks and tribulations, and shared in their many spectacular successes.

In 1930, aged 28, Byrne began constructing a model of the Southern Cross out of wood, but decided to make a metal model instead.

Seeking greater accuracy and detail with his work, Byrne approached Kingsford Smith to obtain blueprints of the Southern Cross. He eventually received them in 1932.

Byrne constructed his model out of over 1000 separate pieces of metal, mostly brass finished in gold and silver plating. The model is scaled 1.27cm to every 30.48cm (a half inch to the foot) on the real Southern Cross, resulting in a wingspan of 91.44cm (three feet).

During construction, Byrne showed his work to Kingsford Smith, who was apparently impressed by the accuracy of the model.

Byrne worked on the model in his spare time, dedicating around 5000 hours to the task over three years, and teaching himself the required construction techniques. He intended to present the model to Kingsford Smith as a gift on his return after another record-breaking flight from England to Australia in November 1935.

When Kingsford Smith and his co-pilot Tommy Pethybridge tragically disappeared in the Lady Southern Cross during that flight, Byrne decided that he would mount his Southern Cross model on a marble pedestal as a tribute to the aircraft and its original crew.

At the time, Byrne said he knew nothing about working with marble so he read books on the subject at the Technological Library. Byrne made the pedestal in four parts using different types of marble, and inlaid it with the Southern Cross constellation in Australian sapphires along with portraits of Kingsford Smith, Ulm, Lyon and Warner.

With the model complete, Byrne began to think of ways to enhance and expand his tribute, intending to write a history of the Southern Cross and its aviators, and gathering images and information about their histories.

Byrne was inspired by Kingsford Smith's affection for the Southern Cross, expressed in his poem 'Ode to the Old Bus', which Byrne added to his growing archive of Southern Cross history:

Old faithful friend – a fond adieu,

These are poor words with which to tell,

of all my pride – my joy in you,

True to the end, you’ve served me well.I pity those who cannot see,

That heart and soul are housed within,

This thing of steel and wood – to Me

you live in every bolt and pin.And so my staunch and steadfast steed,

Your deep and mighty voice must cease.

Faithful to Death if God will heed

My prayer, Dear Pal, you’ll rest in peace.

(Charles Kingsford Smith, ca. 1930)

Building a memorial

Following the tragic disappearances of Kingsford Smith, Ulm and their crews, Byrne decided to add to his model and create further works as a tribute in art to the achievements of the crew of the Southern Cross.

His Southern Cross memorial grew to include these nine separate sections, with finely crafted timber cabinets to hold the elements for storage and transport:

- scale model of the Southern Cross

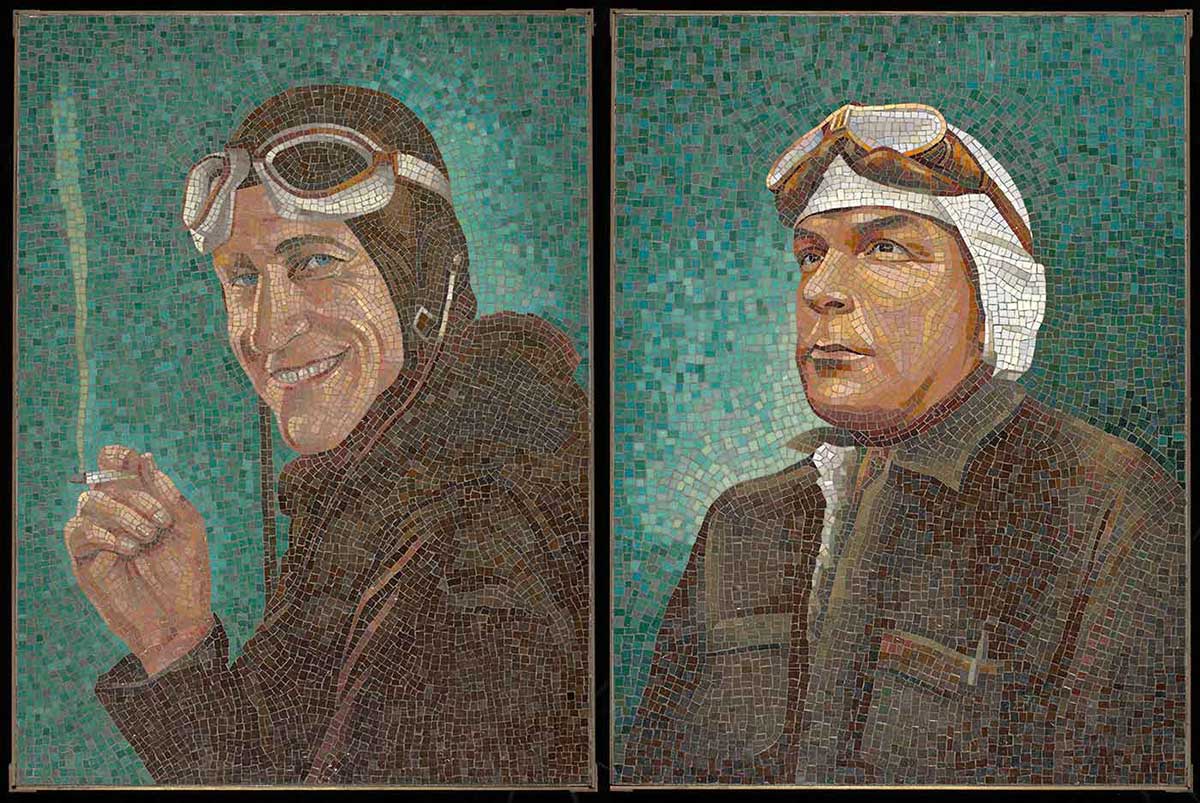

- two oil paintings, portraits of Kingsford Smith and Ulm by Ingrid Ackland

- silver-plated aluminium globe of the world marked with the flights of the Southern Cross

- key to the flights shown on the globe, inscribed with the mileages of each flight

- book, hand-written history of the Southern Cross

- 'Shrine of Remembrance', marble and brass presentation piece to hold section 5

- 'Book of Remembrance', container holding testimonials from 1930s aviators

- three silver plated aluminium globes depicting flights of the Southern Cross

- 200 framed photographs presenting a pictorial history of the Southern Cross.

Byrne worked on the memorial in his spare time, funding each artwork himself:

I used to start work at 7.30 in the morning on the railways and knock off about 5pm. I'd never learned a trade – but I'd come home, have a cup of tea, and then start work on the memorial.

Byrne continued as he had started with the Southern Cross model, working with metals, marble and wood, and when the first version of the memorial was completed in 1938, in total it weighed almost two tonnes.

Byrne first displayed his Southern Cross Memorial at the Royal Easter Show in Sydney in 1938. He returned for a second showing there in 1939, with further exhibitions at the Bathurst and Wollongong shows.

To raise money for his memorial and its exhibitions, Byrne made a number of commemorative Southern Cross lamps to his own unique design – on one side of the lampshade a map of the trans-Pacific flight, and on the other side a map of the trans-Atlantic flight.

The memorial was never finally 'complete', as Byrne continued to add material throughout his life. In 1968, when his memorial was part of the 40th anniversary celebrations of the trans-Pacific flight, Byrne stated that he had spent approximately 100,000 hours across 37 years creating his artworks, mostly by hand.

Mary Ulm's photos

Through Austin Byrne's growing list of aviation contacts, he added a photo album and newspaper clipping scrapbook kept by Charles Ulm’s wife, Mary, to his collection.

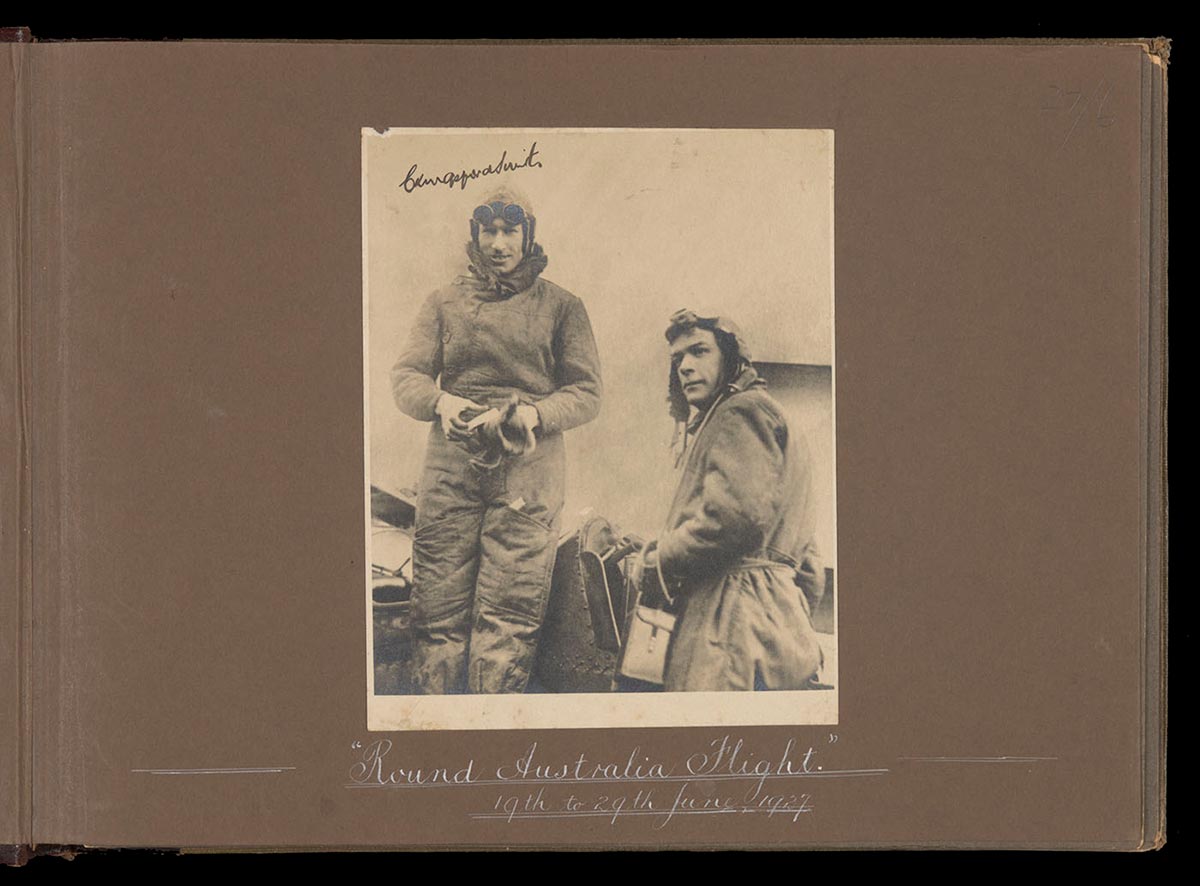

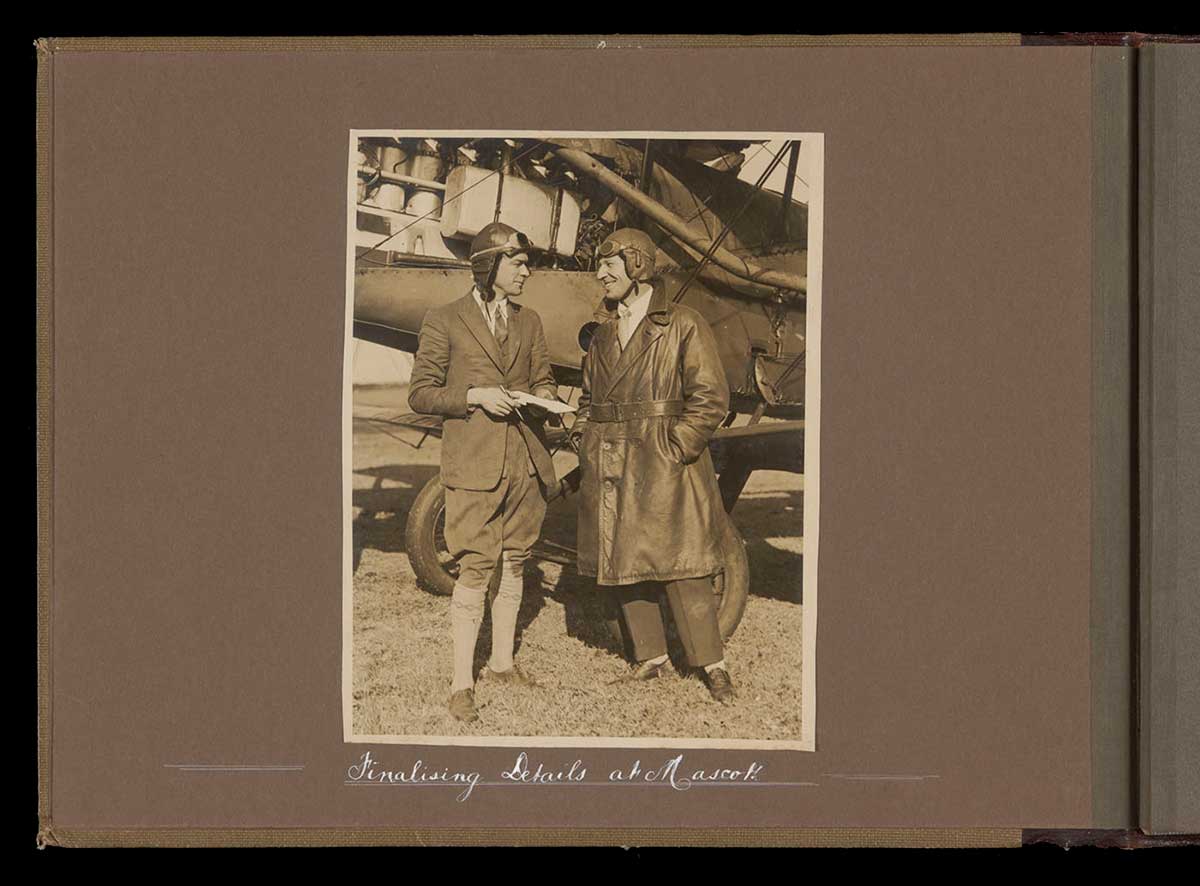

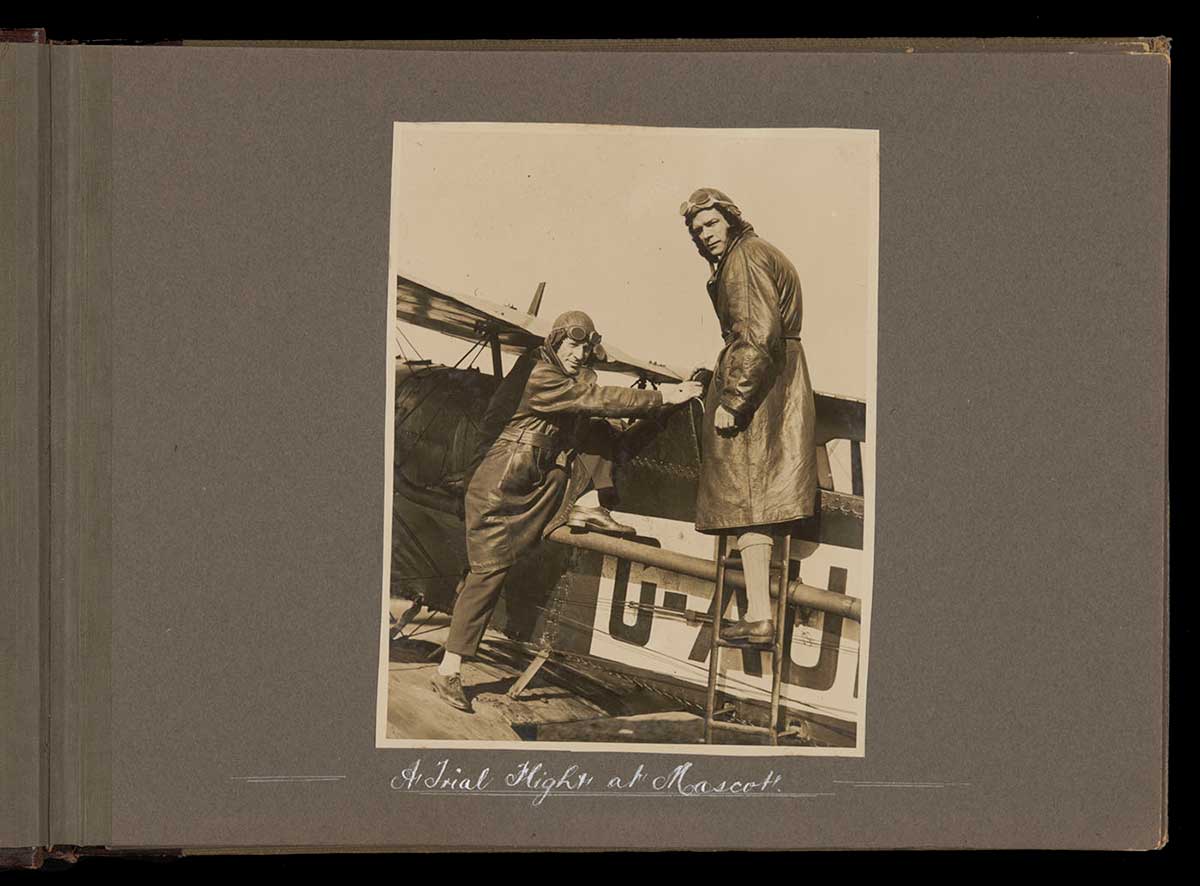

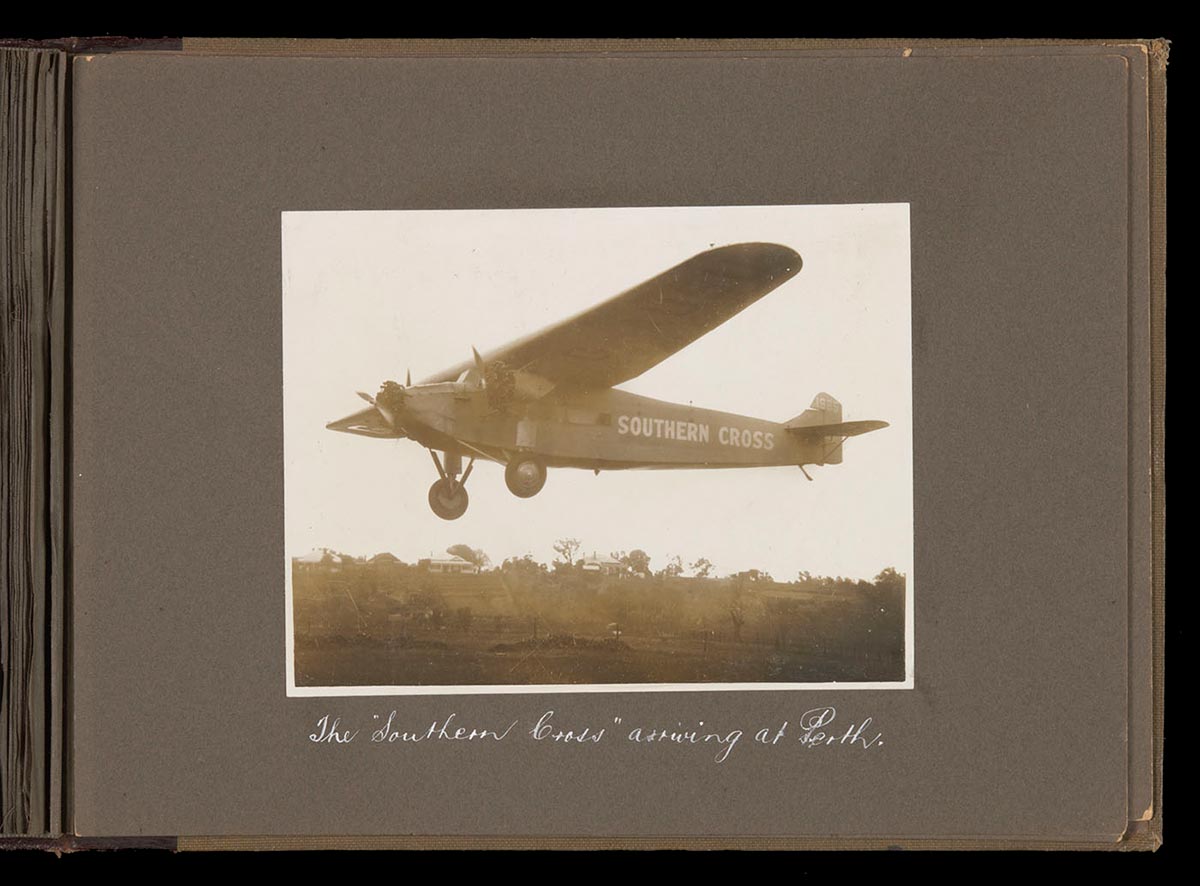

The album records Kingsford Smith and Ulm’s flight around Australia in 1927, the trans-Pacific flight of 1928 from San Francisco to Brisbane, subsequent media appearances and events, flight to Perth, and finally the trans-Tasman crossing to New Zealand.

Taking the memorial to the world

Byrne believed the Australian Government should do more to acknowledge the international cooperation and effort that had gone into the flights of the Southern Cross.

He had always intended his Southern Cross memorial to convey a message of 'thanks' to the people of the Netherlands and the United States of America, and hoped to be able to display his work in those countries.

In 1941 Byrne was invited to exhibit his memorial in the Houses of Parliament in Wellington, New Zealand. The Southern Cross memorial was well received during its three-week exhibition, and raised around £10,000 for the New Zealand war effort. It is believed the funds were used to purchase an air ambulance.

As a thank you, the New Zealand Government purchased a return ticket for Byrne to the United States. His arrival in the US was hampered by an excess duty charged on his memorial.

Unable to pay the required sum, Byrne worked washing dishes in a Los Angeles cafe to raise funds and cover his living expenses while his memorial was held in the customs office. After some media attention, the memorial was released by customs for a significantly reduced fee, and Byrne embarked on a tour of the United States.

Finding extensive support for his work, Byrne exhibited his memorial in schools and other venues, raising an estimated $4 million in stamps and bonds for the American war effort and the Anzac War Relief Fund.

On his return to Australia in 1946 Byrne found little support for his work so he concentrated his efforts on exhibiting his Memorial in Amsterdam, making a clear link to the Fokker Company which had manufactured the Southern Cross.

In 1958 Byrne travelled to Amsterdam with his memorial, exhibiting at Schiphol Airport and raising funds for the Princess Beatrix Polio Fund.

Byrne continued to fund his work independently. In 1967 he retired and sold his house to fund further work on the memorial and his travel to exhibit and attrack support for the work.

During the 1960s the memorial was exhibited at a number of Australian venues, including department stores Grace Bros (later Myer) and David Jones for the 40th anniversary of the trans-Pacific flight.

Permanent home

Byrne first offered the Southern Cross Memorial to the Australian Government in 1946 for £3,500. In 1968 Byrne offered his Memorial to the Australian Government as a donation, and after persistent lobbying by Byrne, it was accepted in 1970 and exhibited for a short period in Kings Hall, Parliament House. Much to Byrne's disappointment, the Memorial was then placed in storage.

During the 1970s Byrne commissioned architectural drawings and made a model of what he hoped would be a permanent building to house the memorial in either Sydney or Canberra. While continuing to seek support for his proposal, he made furniture and flooring components, and a fireplace, that would be installed in the completed Southern Cross memorial building.

In 1980 Byrne borrowed his memorial back from the government for an exhibition at Parafield, South Australia, to raise funds for the construction of a flying replica of the Southern Cross by the Southern Cross Museum Trust.

Hesitant to return his memorial to the government, Byrne continued to lobby for the construction of a separate Southern Cross memorial building, or for his work to be included in a new National Aviation Museum.

In several sections, the Southern Cross memorial, its associated archive and display materials were transferred to the National Museum of Australia in 1984 with additional papers donated by Byrne to the National Library of Australia. Components of this very large collection have since been exhibited by the Museum.

Lasting tribute

Often called 'Ossie' or 'Aussie', reflecting his clear love of Australia, Byrne dedicated his life to building the Southern Cross memorial.

Over the years, Byrne was often asked why he had created the Southern Cross memorial. At a showing of his memorial in the Myer Emporium in Melbourne on the 40th anniversary of the trans-Pacific flight in 1968, Byrne offered this summary his work and experiences:

As time went by my dream enveloped me. It was a dream that has sustained me throughout the major portion of my life. A dream that has taken me to the four corners of the earth. But a dream that is today a reality. Its final culmination now rests in the hands of my fellow Australians. Many will doubt, some may ridicule my story and explanation, but … this is briefly the truthful story of this priceless historical record I have had the great honour and privilege to have visualised, designed and constructed for you, for your children, and for your children’s children.

Austin Byrne died in June 1993, aged 91, having seen his memorial preserved in the National Museum of Australia.

18 Jul 2013

Joy flights, feats and disasters: A journey through 1920s and 1930s aviation in the National Historical Collection

In our collection