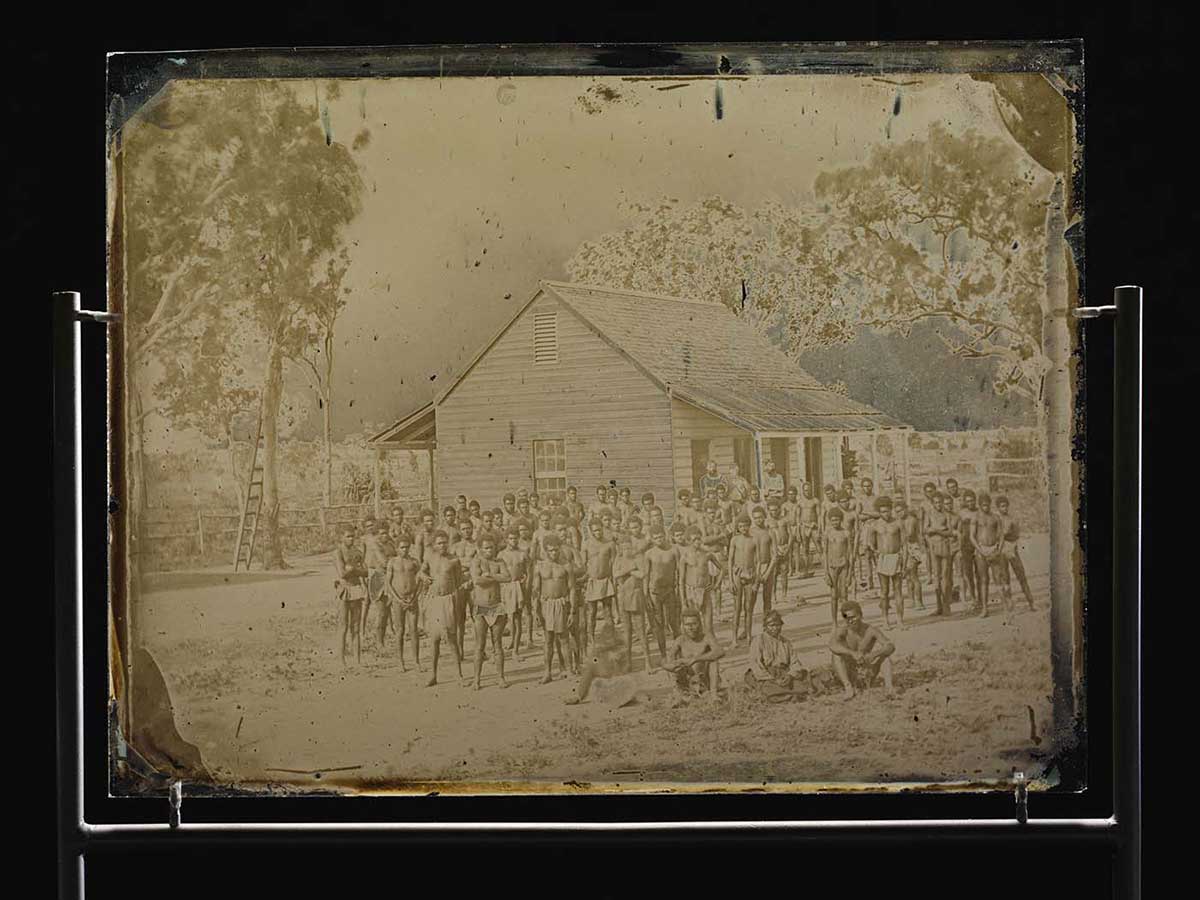

The Richard Daintree collection consists of 10 glass photographic plates depicting various people and places in Queensland between 1864 and 1870.

These images portray miners and their families, Aboriginal people and South Sea Islander labourers and life in mining settlements and missions.

Success and shipwreck

Daintree was one of the earliest European settlers in north Queensland. His pioneering geological surveys led to the first gold rushes in the area inland from Townsville and Bowen. The influx of people who followed helped to establish both ports.

As a photographer Daintree made the only known images of these first remote goldfields. His images were used internationally by the colony to promote immigration and investment.

A collection of Daintree's photographs and geological specimens formed much of Queensland's contribution to the 1871 Exhibition of Art and Industry in London. All was almost lost when the ship carrying Daintree and his family to England was wrecked. Fortunately, the Daintrees survived and and the photographic plates were saved.

Gold to geology

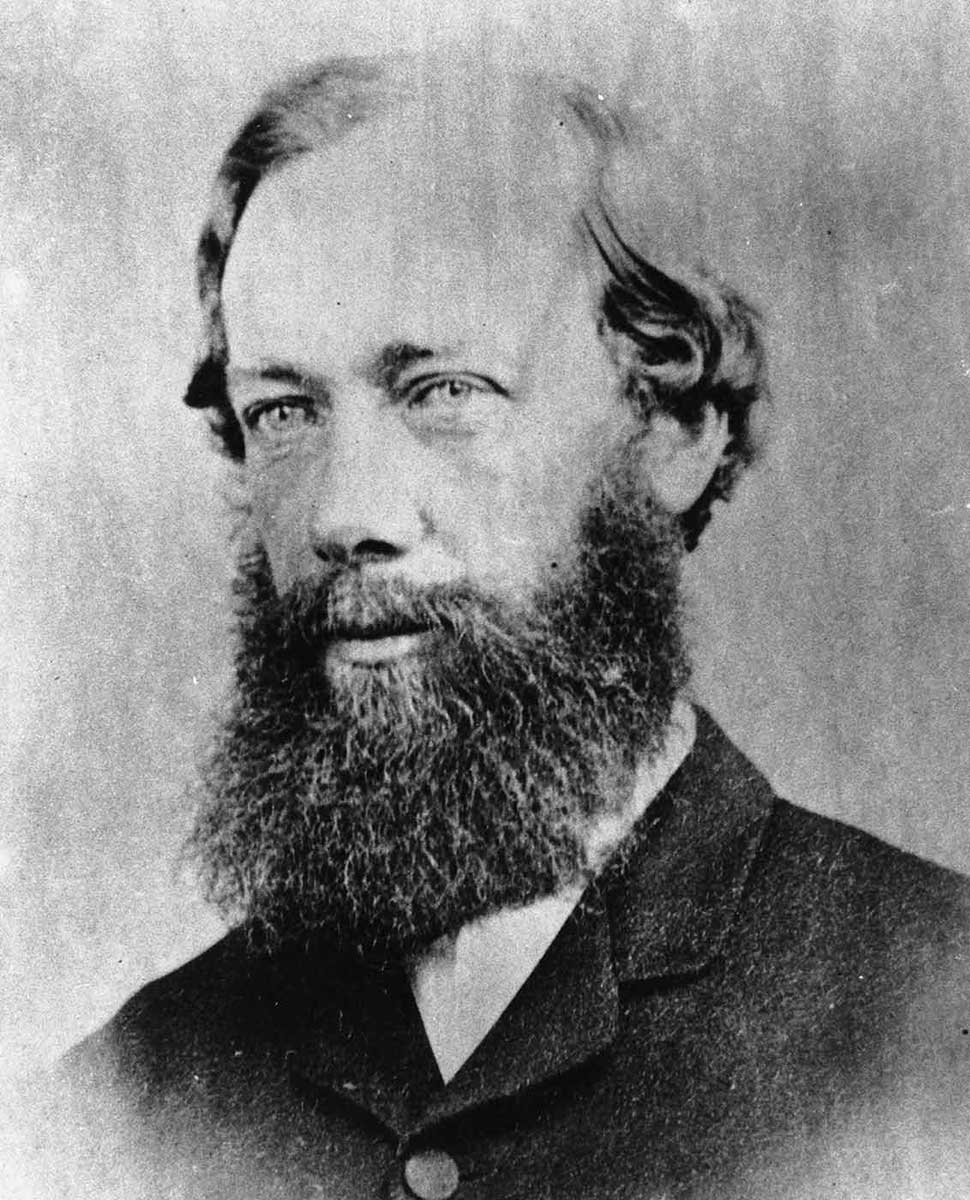

Daintree was born in Cambridgeshire, England in 1832 and grew up on a farm. He studied at Christ's College, Cambridge but was unable to continue due to ill health.

In 1852 he immigrated to the goldfields of Victoria in search of a better climate and riches in the form of gold. Daintree was apparently an unsuccessful digger.

Instead, he was employed as an assistant to the Victorian Geological Survey. In this he found his passion and he returned to England from November 1856 until May 1857 to study assaying and chemistry at the London School of Mines.

While in London Daintree also learnt the technically difficult process of wet plate photography.

Wet collodian photography replaced the daguerreotype and allowed the production of negatives, to make many copies from a single plate. The process was faster and despite involving a more difficult process, it produced very fine details.

Daintree returned to Victoria in 1857 as a fully fledged geological surveyor, and used photography to aid the scientific documentation of his work. The same year he married Lettice Agnes Foot, who had immigrated with her family to Melbourne from England as a child.

In 1858 Daintree began to collaborate with French photographer Antoine Fauchery to produce monthly instalments of images showing life in the Victorian colony. This may have provided the model and inspiration for Daintree to later depict the lives of pioneering Queenslanders.

Early Queensland settlement

Queensland was proclaimed as a separate colony from New South Wales on 10 December 1859. Northern Queensland opened for pastoral settlement from 1861.

Daintree moved north to the Kennedy District, north-east of Townsville. He settled at Maryvale station in 1864 with his wife and 2 children.

Maryvale was one of 3 properties taken up by Hann & Co when the Kennedy district first opened to squatters. The company was a partnership between the Hann family, Richard Daintree and Melbourne financiers Rivett Henry Bland and Edward Klingender.

A depression in the 1860s made life in north Queensland difficult. Daintree struggled to establish Maryvale, where the early flock of sheep had to be replaced with hardier cattle.

Gold in north Queensland

Daintree managed Maryvale until 1870, always with an eye for the geological potential of the region. He conducted independent geological surveys and soon found the region was potentially rich with gold.

In 1865 Daintree lobbied the Queensland Government for a formal geological survey of the Cape River region, but received no reply. Sections of his report appeared in the press and fuelled speculation about the gold-bearing potential of north Queensland.

Daintree conducted several more explorations of the region. He discovered and named the Delaney and Etheridge rivers, along with their gold-bearing potential, as he also did at the Copperfield and Gilbert rivers.

In 1867 he accompanied prospectors to Cape River, where a rush set in, despite Daintree's precautions in the Brisbane Courier that:

I would warn intending miners, that at present water is very scarce, and a sudden pressure of population (especially those who could not afford to pile their wash dirt until the rainy season), would lead to disappointment.

Museum curator Anthea Gunn said this concern for the practical considerations of those who acted on his information is evident throughout Daintree's work, firstly for the colonial prospectors, and later, for potential immigrants to Queensland from overseas.

Political and scientific interests

In December 1867 Daintree renewed his efforts to convince the government to establish a geological survey. He enlisted the support of Reverend WB Clarke, known as the father of Australian geology.

Clarke exerted influence on Mr Walsh, the member for Maryborough, to support Daintree's proposal. In Queensland parliament on 9 January 1868, Walsh moved that the mineral wealth of the colony be investigated. The motion was backed by other members, keen to develop Queensland's resources and the financial opportunities presented by mining.

Daintree was also appointed government surveyor for the northern regions of the Queensland colony. In this role he established the location of goldfields in north Queensland, and collected plant, mineral and fossil samples to further scientific understanding.

Daintree sent about 300 samples to Ferdinand von Mueller at the Royal Melbourne Herbarium. Von Mueller indicated his respect for Daintree by naming a species of wattle Acacia daintreeana. The Daintree River in the Cape Tribulation region was also later named after Richard.

Daintree completed his geological survey of the Cape River area in 1868. He also photographed life at the gold diggings, and some of these images are in the National Museum's collection. The miners' living and working conditions were protrayed in a subset of Daintree's work which focused on people, rather than geology.

In late 1868 Daintree set out again, to survey the Gilbert and Etheridge river regions. By this time he was publicly recognised for his role in discovering gold and hopeful prospectors accompanied him on trips or followed in his footsteps.

Daintree also predicted that the Palmer River area would be a likely goldfield. His Maryvale partner William Hann later led an expedition to the area and confirmed the presence of gold. The Museum's collection also features a sketchbook by Oscar, a young Aboriginal man who lived in the region and depicts mining scenes in his work.

Behind the scenes – Australian Journeys series 10 Oct 2007

Photographer Richard Daintree’s glass plates

International exhibition

The government stopped funding the geological survey in 1869. Soon after, another opportunity arose for Daintree. The Queensland Government was invited to exhibit at the Special Exhibition of Art and Industry to be held in London in 1871.

Daintree successfully proposed displaying mineral specimens and his photographs, to show the scenery, life and towns of Queensland. He was invited to accompany and install the exhibition in London.

On 18 February 1871 Daintree, his wife and five children sailed from Melbourne on the SS Queen of the Thames. Catastrophe struck on 18 March when the Queen was wrecked at Klippestrand near Ryspunt, South Africa.

Daintree and his family survived, but the geological specimens were lost. His photographic negatives and geological sketch map of Queensland were also saved.

The Queensland exhibition was mounted in London and was well received by visitors and government officials.

Daintree was then appointed Queensland's agent-general in London. One of his responsibilities was for Queensland's displays at international exhibitions, to promote the colony's produce and opportunities.

Daintree, an immigrant himself, with experience as a pastoralist and specialist knowledge of geology, was perhaps the ideal figure to promote Queensland as a land of opportunity to the United Kingdom.

Historian Judith McKay noted Daintree's interest in photography and scientific training equipped him to communicate effectively with the public. The style of display that he developed for the Queensland exhibits was used and commended throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

Photography and promotion

Daintree commissioned enlargements from his glass negatives using the new 'autotype' process, which were then painted in oils, creating large colour images to accompany his geological samples.

It is likely the Museum's collection of 10 glass plate positives was made as a part of Daintree's endeavours to promote the colony. They may have been made to create further copies of the negatives.

Their subject matter, primarily that of miners and their living and working conditions, suggest that they may have been used to illustrate the lectures that Daintree gave across Britain to attract immigrants.

Daintree used his position to promote his scientific interests. He spoke at the Royal Geological Society and in 1872, produced Notes on the Geology of the Colony of Queensland. The publication featured illustrations from his photographs of geological features in Queensland and fossils from his and others' collections.

In 1873 Daintree produced Queensland, Australia: Its Territory, Climate and Products, Agricultural, Pastoral and Mineral &c., &c. with Emigration Regulations, complete with maps of the mineral areas for the use of potential miners and investors.

In 1876 Daintree was forced to resign due to ill health. He hoped to pursue his scientific and photographic interests in his retirement and worked to create techniques for photographic magnification of his mineralogical samples. These projects were cut short when Daintree died at the age of 46 in 1878.

Daintree plates

Daintree had arranged for many of the large painted photographs to be returned to Australia. Three were sent to the Hann family at Maryvale, where they remained in 2009.

Others were sent to the Queensland Museum in Brisbane, which also received a large collection of his geological specimens. The photographs were exhibited for many years and are one of few surviving records of early settler life in north Queensland.

The glass plates remained in the collection of the Daintree family in England. During the 1940s most of the negatives were donated to the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, though the 10 in the Museum's collection were kept by the family.

These 10 plates remained in the Daintree family collection until they were auctioned in 1982. The successful bidders at that auction then sold the plates to the Museum in 2007.

In our collection