The remote Northern Territory settlement of Papunya has been heralded as the birthplace of contemporary Aboriginal art.

The Museum has more than 200 Papunya paintings and artefacts in its collection. This includes one of the most significant collections of 1970s Papunya Tula canvases in the world.

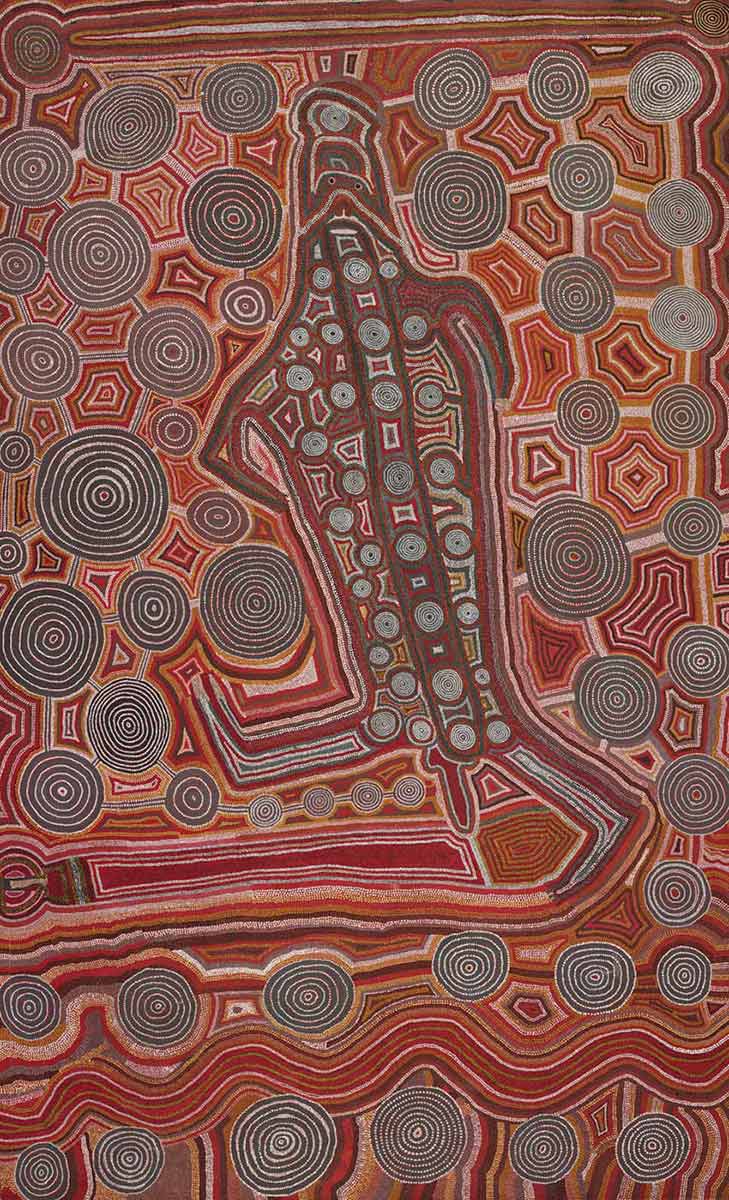

These Papunya paintings are part of a body of work that transformed understandings of Aboriginal art. Papunya artists experimented with colour and style to tell their Dreaming stories linked to land, history and culture.

These artists formed one of the most successful Indigenous arts cooperatives, which still operates today. They worked to ensure the appropriate portrayal of their ancestral Dreaming stories, and to support individual painters and the Papunya community.

Today Papunya Tula is the flagship of a multimillion-dollar Indigenous arts industry.

Papunya settlement

The community of Papunya lies close to the Tropic of Capricorn, 250km west of Alice Springs. See the Papunya map

Papunya was established as a government settlement in 1959, when Aboriginal people came in from the desert. Settlements such as Papunya were established by successive Australian governments under the controversial policy of assimilation. They aimed to socialise Aboriginal people into a European way of life.

Papunya's residents were mainly of the Luritja and Pintupi language groups, but its residents also included people from the Anmatyerr, Warlpiri and Kukatja groups. Some of the Pintupi men had very limited contact with Europeans.

Their traditional country lay hundreds of kilometres west of Papunya in the Gibson Desert, where they had lived as hunter-gatherers until the 1960s. For many Pintupi, Papunya was their first experience of life in a European settlement.

The combination of different language groups, with varying degrees of contact with Western influences, made for a potent mix of Indigenous cosmopolitanism and alcohol-fuelled inter-tribal strife. To many Aboriginal people Papunya was a sad place. Yet it also gave rise to a revolution in Australian art.

Papunya art movement

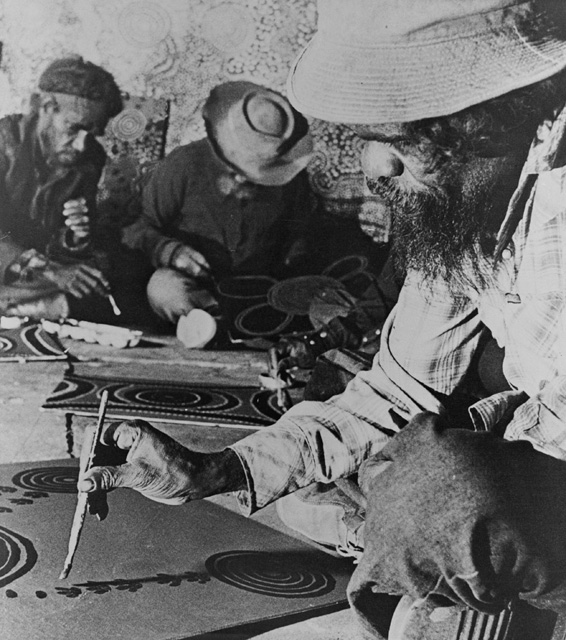

In 1971 a group of Papunya Aboriginal men, with the assistance of school teacher Geoffrey Bardon, began to paint designs on various materials. Their work generated interest in the community and more men started to paint.

These early Papunya works were created in the Central Australian desert – often by a group of men working to a senior artist. Brushes were dipped into acrylic paints as the men worked their way across the canvas. Dots, lines, footprints and circles all gradually came together in a form that would be recognisable to many in years to come.

In 1972 the artists successfully established their own cooperative, Papunya Tula Artists.

Early Papunya artists

Anatjari (Yanyatjarri) Tjakamarra

Pintupi language group, about 1938–92

Born in remote southern Pintupi country, Tjakamarra was one of the last of his compatriots to leave his traditional lands.

He was part of the original 1971 group of Papunya painters, and produced meticulous work of great precision.

Tjakamarra moved to Tjukurla, Western Australia, in the early 1980s and was based there for most of the decade.

In the late 1980s, after a break from painting, he resumed work for Papunya Tula Artists in Kiwirrkura. He had a solo exhibition in New York in 1989, from which the Metropolitan Museum of Art purchased its first work by a Western Desert artist.

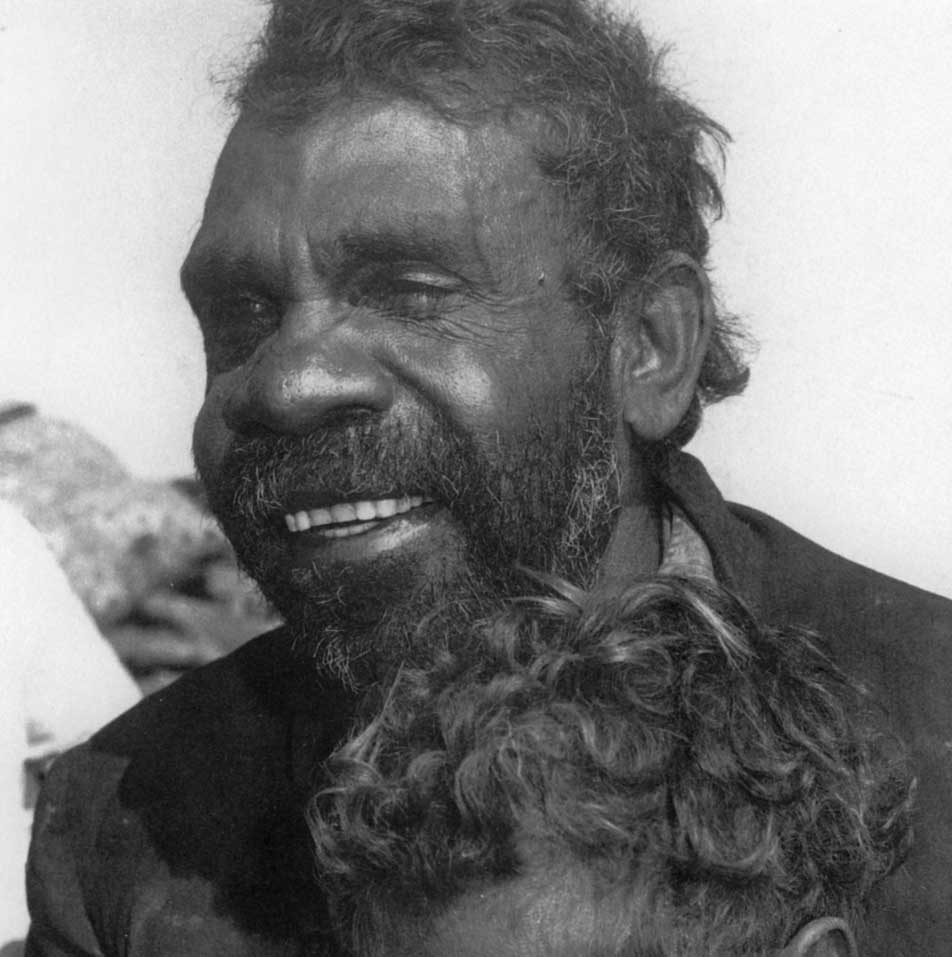

Kaapa Tjampitjinpa

Anmatyerr/Warlpiri/Arrernte language groups, about 1926–89

Tjampitjinpa, his younger 'brother' Dinny Nolan and cousins Tim Leura, Clifford Possum and Billy Stockman Tjampitjinpa, all grew up on Napperby Station, north-west of Alice Springs, where Tjampitjinpa was born and later initiated.

He worked as a stockman before moving to Papunya in the early 1960s.

A forceful and highly intelligent man, Tjampitjinpa was a key figure in establishing the painting movement, becoming Papunya Tula Artists' first chairman.

He was principal artist for the collaborative painting of the famous mural at Papunya School. Tjampitjinpa won first prize in the 1971 Alice Springs Caltex Art Award, the earliest public recognition of a Papunya painting.

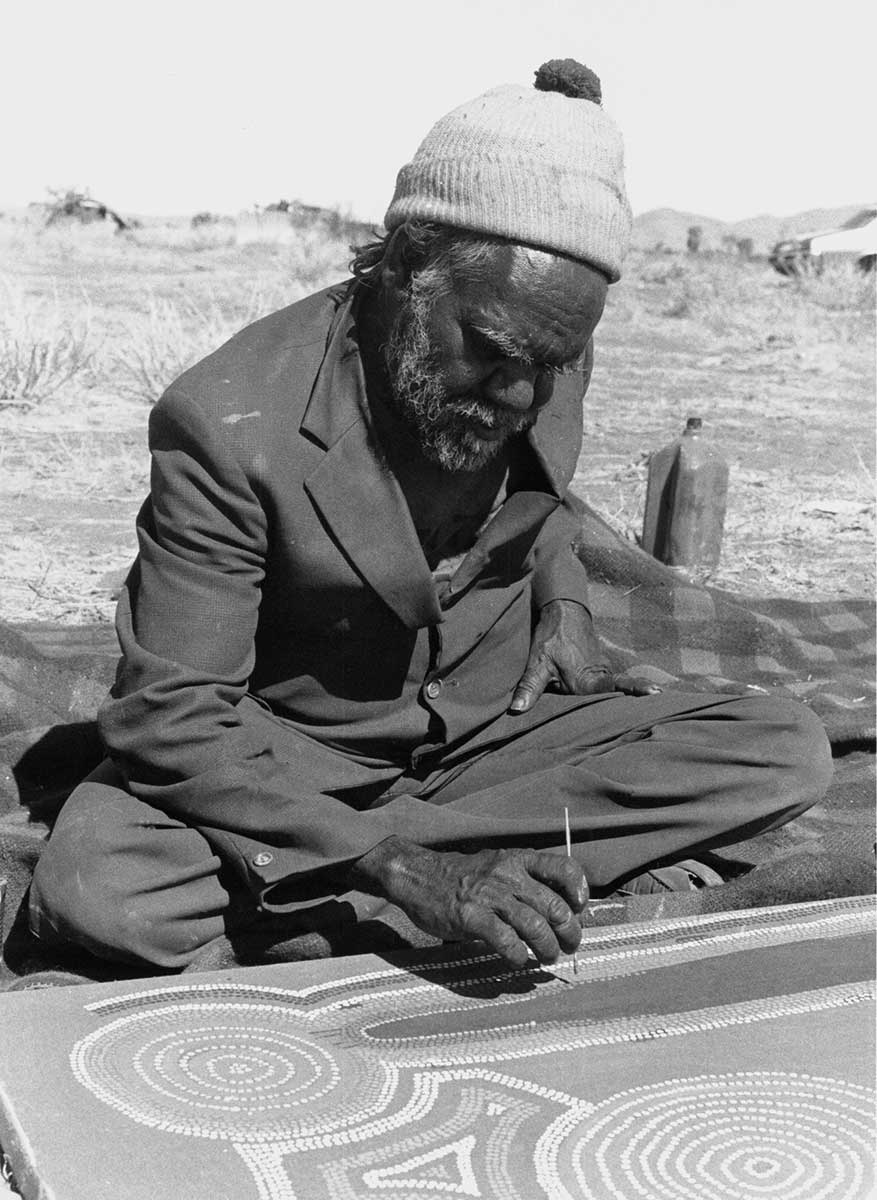

Uta Uta (Wuta Wuta) Tjangala

Pintupi language group, about 1926–90

Tjangala was conceived at the site of Ngurrapalangu in the Kiwirrkura area of the Gibson Desert, and through this was connected to the Yina (Old Man) Dreaming story that runs from Ngurrapalangu and through Yumari.

He was one of the original Papunya group of artists and an inspirational figure in the art movement, painting continuously until the late 1980s.

In the late 1970s he travelled extensively through the fringes of the Western Desert and together with other Pintupi leaders developed a plan for returning to their traditional lands.

He finally settled in Muyin, an outstation west of Kintore, in the early 1980s.

Many stories, many meanings

The land in and around Papunya is Tjala country, and includes many sites associated with the Honey Ant Dreaming stories. These stories and designs linked to Dreaming places are seen repeatedly in Papunya works.

The works feature a symbolic language of U shapes, concentric circles, journey lines and bird and animal tracks. Artists used a limited number of motifs to express many meanings. A concentric circle, for example, may indicate a camp, a waterhole or corroboree place. It may also represent all or part of a person, the stem of a tree, the centre of a food plant ancestor or a natural feature such as a hill.

By painting the designs and stories that represent their particular Dreaming places, Papunya artists assert their rights and obligations as Central and Western Desert landowners, entrusted with the ritual re-enactment of the events that occurred at these sites.

The symbols they use are part of a unique visual language which is also used in designs painted on the skin and in elaborate ceremonial ground paintings.

Traditional stories and forms

The technique of combining and recombining motifs allows for a continuation of traditional forms and stories. It also provides potential for individual artistic expression and innovation. Papunya paintings can also be considered for their artistic merit or as the first products of an artificially conceived commercial art industry and the issues associated with its emergence and independence.

Culturally, they can be studied for the ancestral stories they relate, the cultural landscapes they describe, the religious and social relationships between the artists and their assistants, and the iconographic devices used to construct and communicate the stories.

No less significant are the stories of the relationships between the art advisers, the artists and their families.

Aboriginal Arts Board and Papunya

Many of the Museum's Papunya works were collected by the Aboriginal Arts Board of the Australia Council during the 1970s. The Aboriginal Arts Board was created in 1973, with members who were all Indigenous Australians.

The Board's non-Indigenous founding director was Bob Edwards, who had a strong association with Indigenous communities. Papunya was represented by artists Tim Leura Tjapaltjarri and Billy Stockman Tjapaltjarri.

The Board fostered Aboriginal arts, literature, theatre, dance, music, painting and craft. It also provided grants for Aboriginal communities to employ managers and to help preserve and sustain Aboriginal culture, arts and crafts.

Some of the Papunya paintings bought by the Aboriginal Arts Board were lent or given to Australian embassies around the world. Others were donated to public museums and galleries in Australia and overseas. These gifts helped to raise the profile of Aboriginal art in the commercial art market.

The Aboriginal Arts Board also purchased paintings for display in travelling exhibitions, which toured Africa, Canada, Indonesia, Japan, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States between 1973 and 1981.

In the 1980s the Board wound up its exhibition program. In 1990 the historic collection of Papunya paintings was transferred to the National Museum in Canberra.

Dr Bob Edwards AO

Bob Edwards is an archaeologist, curator and administrator who helped Papunya Tula Artists reach out to the world in his role as foundation director of the Aboriginal Arts Board.

Edwards' fascination with Aboriginal culture started while researching stone tools in the late 1940s.

The former Curator of Anthropology at the South Australian Museum was instrumental in significant developments relating to the knowledge and understanding of Indigenous cultures and heritage management in Australia.

Edwards was convinced that Aboriginal artists should determine their future and retain control over their heritage.

He worked with the Aboriginal Arts Board and communities such as Papunya to broaden exposure to Aboriginal art and increase access to markets.

Edwards is also a former chairman of the Council of the National Museum of Australia and founding director of the Museum of Victoria. He formally retired as a director of Art Exhibitions Australia in 2000 and retains international credibility in museum and exhibition spheres.

Setting the story straight

In 1974 Edwards visited Yayayi, an outstation community 42 kilometres west of Papunya, to purchase paintings for the Aboriginal Arts Board. During the visit, Uta Uta (Wuta Wuta) Tjanagla was recorded on film by Ian Dunlop speaking about Edwards:

Ngaatja purlkangka wangkanytja tjiinyangka. Watjarni walypalangku tjukarurru katinytjaku. Kungka kutjarrapula, ngaa kutjarra katinytjaku.

This translates to:

I want to tell this story for that important man here [Bob Edwards]. I want these whitefellas here to take the proper story, the straight story. Then they can take these paintings about the Two Women Dreaming, they can take these two important ones.

1980s and new beginnings

The year 1981 was a watershed in the history of the Papunya painters. Their work was publicly recognised as part of contemporary Australian art when three Papunya paintings were selected for the Australian Perspecta 1981 exhibition at the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

Also in 1981, many of the Pintupi artists returned to their homelands, far to the west of Papunya. Over the next two decades they established settlements at Kintore and later Kiwirrkura, which became the operational centre of Papunya Tula Artists.

Women at Papunya

Throughout the 1970s Aboriginal women at Papunya were discouraged from painting in their own right. Papunya Tula's management believed allowing women to paint on canvas might stretch their resources. Instead the women carved and painted coolamons (dishes) and dancing boards.

By the early 1980s women were increasingly encouraged to help the all-male painters of Papunya Tula Artists. Daisy Leura Nakamarra was the first female painter from the Western Desert art movement to be represented in a public collection.

Papunya collection

Many of the works in the Museum's Papunya collection had been seen by very few people in Australia, until they went on show in Canberra for the 2007 exhibition Papunya Painting: Out of the Desert.

The exhibition brought together themes of land and people through canvases of vibrant colour.

Papunya community elders, artists and their families worked with the Museum to make a great contribution to the exhibition, which showed the perpetuation of a living culture. Key works also toured to China.

The Museum continues to build its collection of Papunya material.

In our collection