A collection of protest material from meetings across the Murray-Darling Basin document the attitudes of riverine communities towards their local environment and industry at a time of resource scarcity and ecological change.

Murray-Darling Basin Authority staff collected the placards, posters, flyers, T-shirts and umbrellas at meetings in Deniliquin, Dubbo, Griffith, Mildura, Narrabri, Narrandera and Shepparton.

The meetings were organised by the Authority as part of the process to develop a plan to return water and ecological wellbeing to the river system.

The collection donated to the National Museum helps to document tensions arising from the ecological impact of an expanding irrigation industry in an area that provides more than a third of Australia's food supply. It also complements the Museum's growing collection of protest material, and material from Murray-Darling Basin communities.

The Murray-Darling Basin

The Murray-Darling Basin covers most of inland southeast Australia and is drained by the nation's most substantial rivers including the Murray, Murrumbidgee, Lachlan and the Darling.

It covers an area from north of Roma in Queensland to Goolwa in South Australia. The Basin encompasses three-quarters of New South Wales and half of Victoria.

It covers the territories of about 30 Aboriginal language groups.

Agricultural significance

More than two million people live in the Murray-Darling Basin, while the region's produce nourishes many more.

The Basin contains 65 per cent of Australia’s irrigated agricultural land and the Murray-Darling Basin Authority estimates the region produces 53 per cent of Australian cereal, 95 per cent of oranges, 54 per cent of apple production and supports 62 per cent of Australia's pigs, 45 per cent of sheep, and 28 per cent of cattle.

Indigenous and environmental significance

The relatively fertile character of the Murray-Darling Basin and its capacity for export commodity production meant its Aboriginal people suffered great hardships during the colonial period. Populations plummeted as pastoral and agricultural colonisation advanced.

The advent of modern, industrial systems of farming and production profoundly altered the ecological systems of the Basin.

Some areas of great biological value remain. Of particular significance are the Victorian riverine forests of Barmah and Gunbower, and adjacent floodplains in New South Wales, that together form the largest forest wetlands in southern Australia, and are home to a variety of threatened species.

Blue-green algae impact

The amount of water extracted from rivers in the Murray-Darling Basin more than doubled in the late 20th century. In December 1991 a spectacular bloom of blue-green algae appared along the Darling River.

Fed by livestock manure and industrial fertilisers washed from paddocks, the toxic bloom stretched for more than 1000 kilometres along the depleted, stagnant river.

This event captured the attention of national and international media. The New South Wales Government declared a state of emergency. No longer could Australians ignore the ecological consequences of an expanding irrigation industry.

In 2012 federal water minister Tony Burke described the effect of the 1991 algal bloom on water reform in the Murray-Darling Basin:

It stopped being just a negotiation between the States, and the rivers started to negotiate back. And the rivers negotiated harder than any of the states. Because they effectively said: "If you run the system into the ground then none of you can use the water".

For the two decades following the Darling River algal bloom, successive Federal governments tried unsuccessfully to secure agreements with state governments to restore river health across the Murray-Darling Basin, amid increasing awareness about climate change and drought.

Murray-Darling Basin Authority and the Basin Plan

In 2007 the Commonwealth Parliament passed the Water Act. Out of this legislation came the Murray-Darling Basin Authority, charged with the task of developing a plan to return water and ecological wellbeing to the river system.

In 2010 the authority released its draft Guide to the Proposed Basin Plan, before holding community consultation meetings in irrigation districts across the Basin.

Irrigation industry concerns

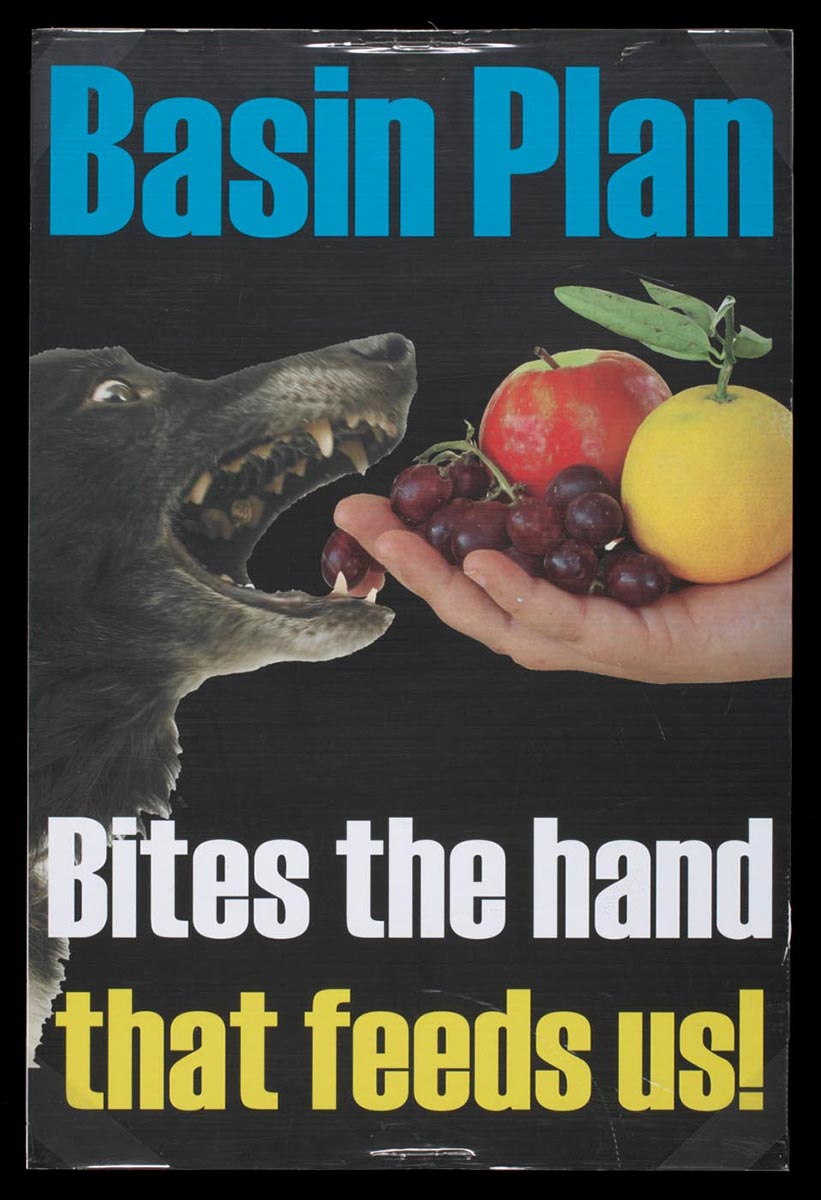

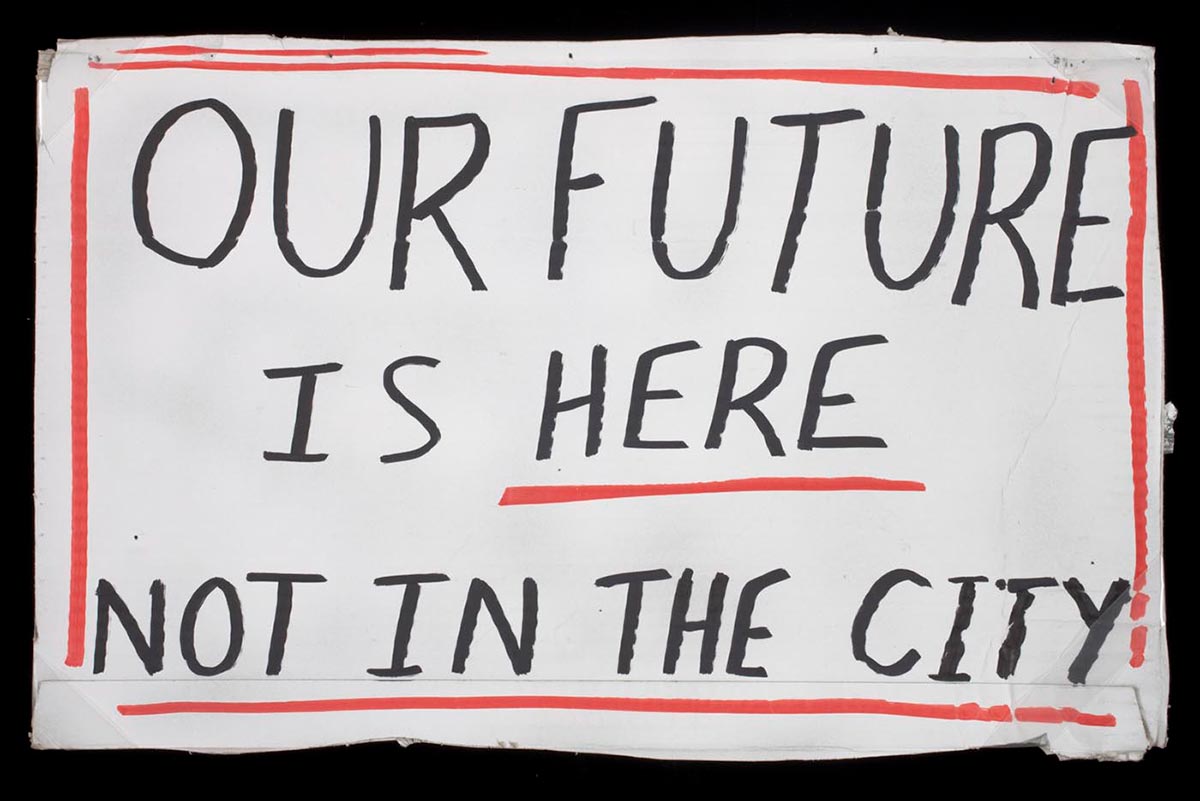

Irrigators and their communities fiercely condemned the proposals in the plan. Farmers and business owners angrily declared the reforms would devastate their towns and livelihoods.

At Griffith, a large town in the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area of New South Wales, the Griffith Business Chamber and the Murrumbidgee Valley Stakeholders irrigation industry group designed placards with simple, forceful messages about the local and national consequences of water reform. Outside the meeting, farmers burned copies of the proposed plan.

The Commonwealth Government responded to the protests by announcing an inquiry into the impacts of the water reform proposals on irrigation communities.

Days later the Murray-Darling Basin Authority decided to conduct its own study into possible social and economic effects, while maintaining a controversial argument that, according to the Water Act, the Authority had to prioritise the environment over people.

The Australian Broadcasting Commission quoted Authority chairman Mike Taylor in Griffith: 'The Act mentions the environment 258 times, sustainability 60 times, irrigated agriculture three [times] and agriculture once. I think it’s important to understand where the Act is focused'.

The loud and angry protests continued at community meetings. Within weeks of the Griffith meeting, Mike Taylor had resigned.

In 2011 the Murray-Darling Basin Authority's new chairman, Craig Knowles, announced the Authority was committed to a strengthening of community involvement in designing and implementing the Basin Plan and a revised plan was released in November 2011.

In a speech to the Farm Writers' Association of New South Wales Mr Knowles said:

We are not willing to experiment with the lives of real people living real lives in the Basin. The result should, indeed must, have regard for the people who live in the Basin, their lives and livelihoods, not dealt out because they don't fit in with some scientific model, but dealt in because they are valued and needed as part of our great Australian landscape.

Environmental and scientific concerns

The federal Opposition voiced concerns about the draft plan and environmental groups long worried about the Basin continued to protest.

The influential Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists abandoned negotiations and called for the plan to be withdrawn.

The group declared that the revised plan would transfer $20 billion from the Australian community to irrigators while failing to deliver a healthy river system.

Riverina and Murray Regional Organisation of Councils (RAMROC) chairman Terry Hogan welcomed the withdrawal of the Wentworth Group and said he expected 'a more balanced outcome', as a result.

In November 2012 the Murray-Darling Basin Authority presented a final version of the Basin Plan to the Australian Government. It stipulated a return of at least 2750 gigalitres of surface water to Basin rivers and wetlands, mainly through the building of new, more efficient irrigation infrastructure.

Parliament signed the revised Basin Plan into law on 22 November 2012.

A record of protest

The Murray-Darling Basin Authority acquisition builds on the Museum's collection of protest material.

This includes the Bob Brown collection of material linked to Brown's environmental protests in Tasmania, the Kristina Tucker collection of protest clothing from the National Apology to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants first anniversary protest in Canberra and a collection from the Movement Against Uranium Mining from the 1980s.

In our collection