Thoughts of riding in France were never far from cyclist Hubert Opperman's mind as he raced to victory after victory in Australia during the 1920s.

Better known as 'Oppy', he finally got his chance in 1928 when his charismatic manager and owner of the Malvern Star bicycle company, Bruce Small, raised enough funds to send a 4-man team to compete in the Tour de France.

Efforts to find additional teammates once they arrived in Europe failed and Oppy's team had to compete against experienced and well-equipped squads of 10 men.

While outright victory was impossible, Oppy – the strongest of his team – finished in a respectable 18th position.

Tour de France

Hubert Opperman was born in Rochester in Victoria in 1904. His father moved the family around the country while he was searching for work and prospecting for gold. Eventually, to give Hubert more stability, he was taken in by his grandmother who lived in Melton on the western outskirts of Melbourne. This where he first learned to ride a bicycle.

After he left school Oppy worked for the Post-Master General’s office, delivering mail by bicycle. He also began winning cycling races at the junior level and working his way up the various ranks.

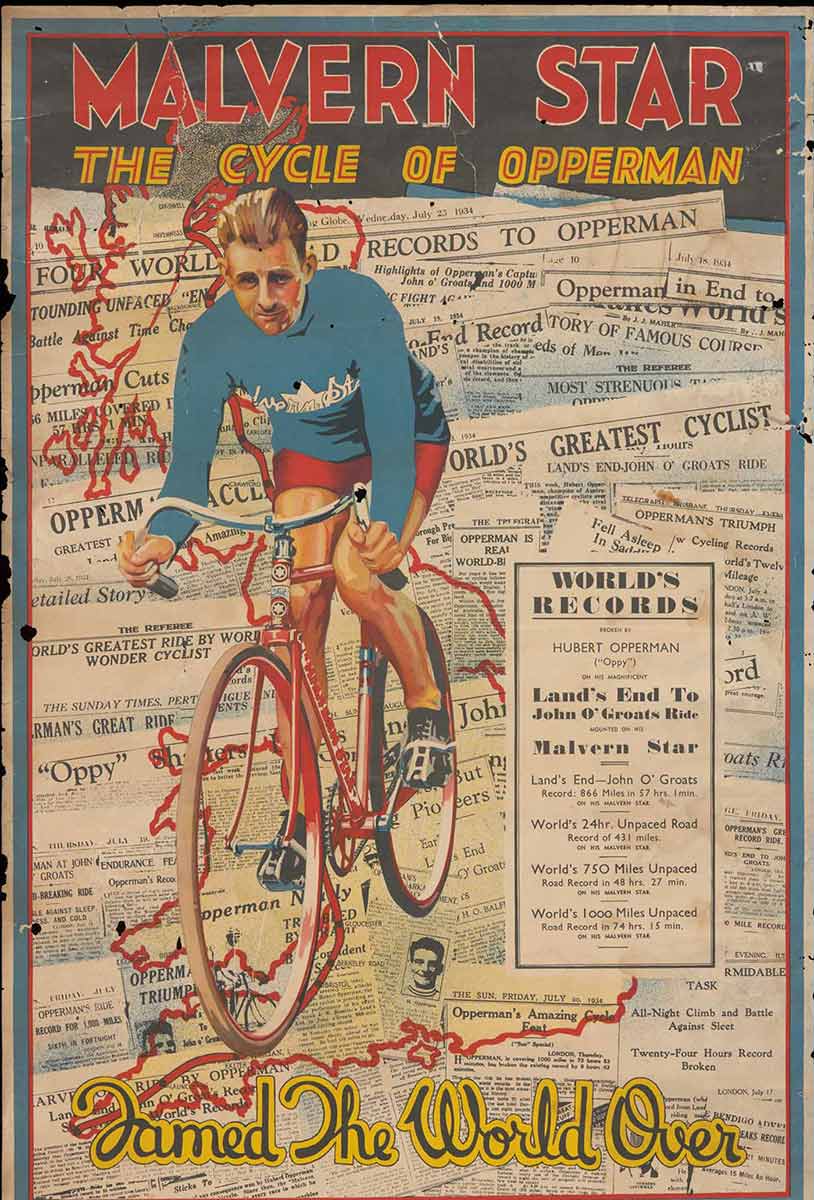

After placing in a major cycling race when he was 19 years old, he attracted the attention of Malvern Star bicycles, and in particular the manager of Malvern Star, Bruce Small. Oppy then went to work for Small as a salesman, but was allowed reasonable time to continue his training.

For most of the 1920s, Oppy was the national road cycling champion. He was 24 years old when he left Australia for the first time in 1928 to compete in the Tour de France.

Cycling phenomenon

Oppy impressed at the 1928 Tour de France, but it was his performance one month later at the Bol d'Or (Golden Bowl) – raced non-stop over 24 hours – that galvanised his reputation.

During the event, his rivals sabotaged his bicycles, filing the chains so thin that they snapped under pressure.

Forced to ride a heavy touring bike while his racing machines were repaired, Oppy lost valuable distance to his opponents. Enraged at the foul play, he cycled on, refusing to leave the track in order to relieve himself.

After hours of non-stop riding, spectators saw a golden stream flowing from Oppy's wheel onto the track and into the path of his rivals. They roared in support and chanted Oppy all the way to eventual victory.

Oppy had completed just over 900 km in 24 hours, but when he tried to stop at the end of the race Bruce Small convinced him to continue riding to break the 1000 km record. The crowd chanted into the night, 'Allez Oppy, Allez!', as he rode for another 80 minutes to achieve the milestone.

Before leaving France, Oppy was voted the most popular sportsman in Europe in a readers' poll conducted by the sports paper L'Auto, ahead of tennis champion Henri Cochet. For French cycling fans and the sporting press he was a 'new cycling marvel'. They dubbed him 'le phenomene' (the phenomenon).

Oppy arrived back in Australia sporting a new beret, a tribute to the generous welcome and support he had received from the French people. In his suitcase he had at least another three. He would wear them for the rest of his life.

This dress statement was a decisive moment in the process that changed Oppy from a sportsman to a public figure. It marked him out as a sophisticated Europhile and the physical equal of the best racers in the world, but it never distanced him from the sports loving public or diminished his great pride in Australian cycling.

For the next decade, Oppy's displays of energy and stamina enthralled Australians as he set a number of inter-city and trans-continental cycling records. When he retired to join the Royal Australian Air Force as a physical trainer in 1939, he was a national sporting icon, as recognisable as Don Bradman or Phar Lap.

Public life

After the war, Oppy attracted the attention of a resurgent Liberal Party. In 1949, he stood for election in the federal electorate of Corio in Victoria, defeating John Dedman, Labor’s Minister for Post-War Immigration.

He retained the seat for the next 17 years and held the portfolios of shipping and transport (1960–63) and immigration (1963–66).

In 1967 Oppy moved to Valletta as Australia’s first High Commissioner to Malta. He was knighted in 1968 and retired from public life in 1972.

Oppy's longtime manager, Bruce Small, also ventured into politics in later life. After giving up his business interest in Malvern Star in the 1960s, Small became involved in property development on the Gold Coast, Queensland, where he made millions building Florida-style canal estates. In 1967 Small was elected Mayor of the Gold Coast and encouraged tourism with bikini-clad meter maids.

Opperman's legacy

In later life Oppy faded from popular imagination in Australia. Yet he remained an inspiration to the cycle-loving French.

He attended the centenary celebrations of the gruelling Paris–Brest–Paris 1200 km event in 1991 – 60 years after his famous win of that same ride – and received the Gold Medal of the City of Paris.

In February 1996 Oppy wrote to inform the National Museum of Australia that his 'most ancient of berets', worn in Europe between 1928 and 1931, was on its way to Canberra.

He handed over this treasured object with some solemnity, for it had 'meant so much to [him] during a varied life'.

Less than two months later, at the age of 91, Oppy died at his retirement village, after suffering a heart attack while riding his exercise bike.

Cycling in Australia series 21 Mar 2013

The Human Motor: Sir Hubert Opperman and endurance cycling in Australia

In our collection