Harry Clarke raced bikes for most of his life. He first fell in love with cycling while working as an apprentice engineer in Melbourne during the Second World War, after a fellow worker persuaded him to participate in a local competition.

Clarke juggled work, trade school and training, to clock up more than 200 miles, or 320 kilometres, of riding each week, often by torchlight.

He raced for the Richmond and Kew Amateur Cycling clubs, and turned professional after failing to qualify for the 1956 Melbourne Olympics, riding for Richmond.

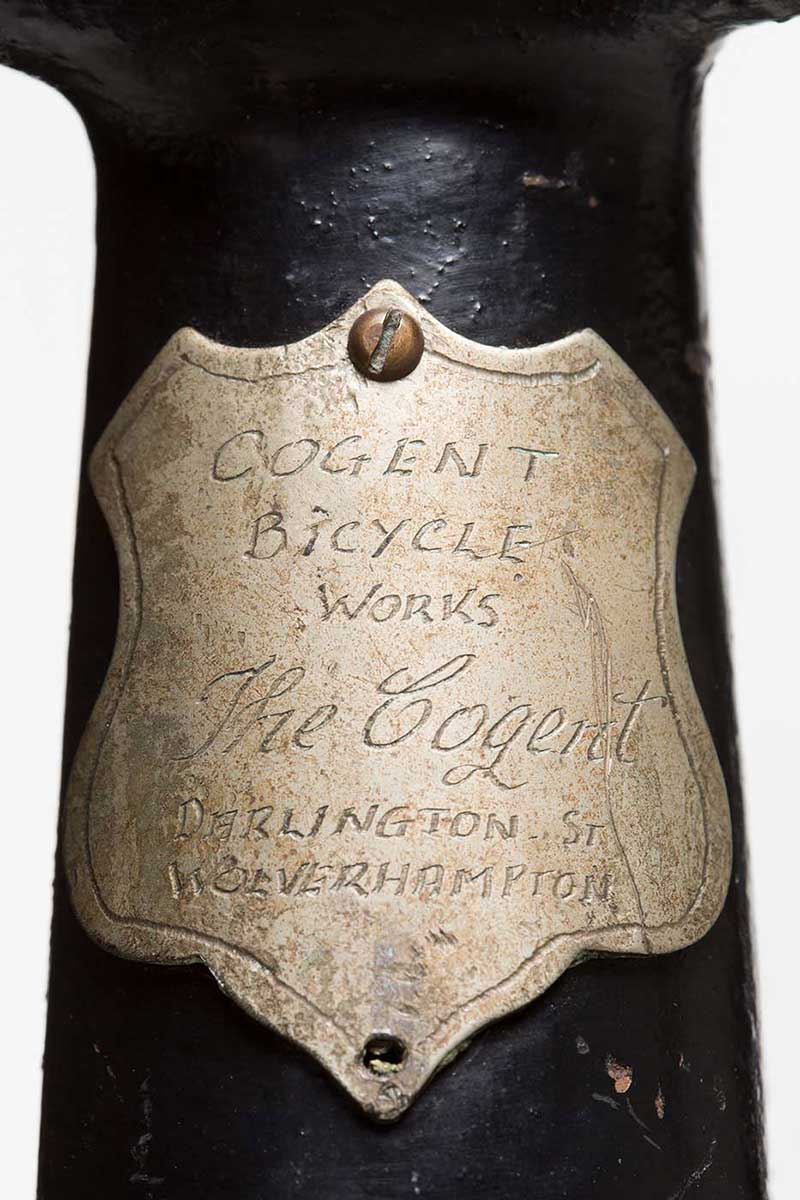

At an antiques auction in his late 50s, Clarke impulsively purchased a machine that would shape the rest of his life, an 1884 English-made penny-farthing bicycle. He named it ‘Black Bess’.

Clarke offered his beloved penny-farthing to the National Museum in 2013 with some sadness.

In his late 80s he was unable to ride a conventional bicycle let alone a penny-farthing, thus bringing to an end a lifetime of riding, racing and exploring the world by bike.

Romance of cycling

Harry Clarke recalls catching the cycling bug while working as an apprentice. A typical day involved working a 12-hour shift from 7am, then night school which finished at about 9pm. He would then hope to get in a few hours training, riding by torchlight with a few mates. Clarke would race for his club each Saturday.

As a teenager, each Sunday he and his cycling friends would gather on Whitehorse Road in Melbourne waiting for trucks and vans transporting people up to the Dandenong Mountains to enjoy picnics and bush walks. Many of the vehicles were open furniture vans with bench seats laid out along the sides. With the rear loading platform raised into a vertical position, a careful cyclist could easily keep up with the truck by riding in the slipstream.

Part of the attraction was trying to ‘make time’ with the girls riding in the vans who would pass food and lollies to the riders through the side rails.

Sometimes they would follow the vans as far as Mount Donna Buang (80 km from Melbourne), spend the day with the picnickers and ask for a lift with their bikes back to town in the afternoon. Still dressed only in their cycling attire, they ‘naturally hoped to cuddle down’ with the girls in the back of the van.

Australia's cycling craze

Penny-farthing bicycles first arrived in the colonies in the 1870s. Difficult and dangerous to ride, these towering machines had riders sitting at more than 2.5 metres in the air.

Nevertheless, they helped inspire the great enthusiasm for cycling, which peaked in the 1880s when the diamond frame, chain-driven 'safety' bicycle arrived on the scene.

High wheelers were soon rendered obsolete, as safety bikes became the dominant form of personal transportation in the colonies.

The later decades of the 20th century, however, saw a revival of interest in vintage cycles.

Harry Clarke was hooked. Once he learnt to ride, a process that involved numerous spills, he competed in the National Penny-Farthing Championships in Evandale, Tasmania, winning the relay event in his first race.

Clarke attended the annual Evandale festival for the next 20 years, winning the veterans category in 1985, 1993, 1995 and 1997.

Re-enacting the Burston and Stokes penny-farthing journey

In 1988 Clarke, then president of the Vintage Cycle Club of Victoria, joined 23 other cycling enthusiasts to mark the centenary of the round the world journey made by Melbourne penny-farthing riders George Burston and Harry Stokes.

Celebrations included a partial re-enactment of their adventures, with the group spending 2 weeks riding from Melbourne to Sydney on their penny-farthings, following the original route where possible.

In our collection