Four iconic maps illustrating the history of the Great South Land and its role in the development of European cartography and voyages of discovery have been acquired by the National Museum of Australia.

An ancient myth of a Great South Land was powerful and persistent despite many unsuccessful journeys to find it. These four maps illustrate the survival of the myth in the work of the 16th century's leading cartographers.

These maps represent the state of geographic knowledge that Captain James Cook's voyages finally rendered obsolete, by disproving the existence of a Great South Land.

Lands that must exist

The Ancient Greeks, using astronomical observation and advanced mathematics, discovered that the world was not flat, but a sphere comprised of northern and southern hemispheres. Unable to explore distant regions which 'must' exist, philosophers could only imagine what might be found there.

Pythagoras (580–500 BC) asserted that the world was divided into five zones – two frigid zones at the poles, two temperate zones and a torrid zone at the equator, which he believed formed an impassable barrier between the hemispheres.

Aristotle (384–322 BC), building on Pythagorean thought, argued that symmetry was nature's favoured form and if the world was symmetrical, then a Great South Land must exist to counterbalance the lands of the north.

Theories about the Great South Land were given their most authoritative form in the maps of Claudius Ptolemy (90–168 AD). During the Middle Ages the renewed popularity of Ptolemy's world map and the expansion of trade routes encouraged belief in the existence of rich but undiscovered lands.

Voyagers from the late 15th century returned with charts of previously unvisited regions to add to existing geographical maps. New maps were drawn that combined increasingly accurate representations of the new world with entirely speculative entities such as the Great South Land.

Myth of the Great South Land

When Lieutenant James Cook sailed for Tahiti in 1768, the maps he carried represented the sum of European knowledge of the Pacific. Vast expanses of ocean remained unexplored, few islands had been accurately plotted, and hopes were entertained that a southern continent – equal in size and wealth of the Americas – might be discovered.

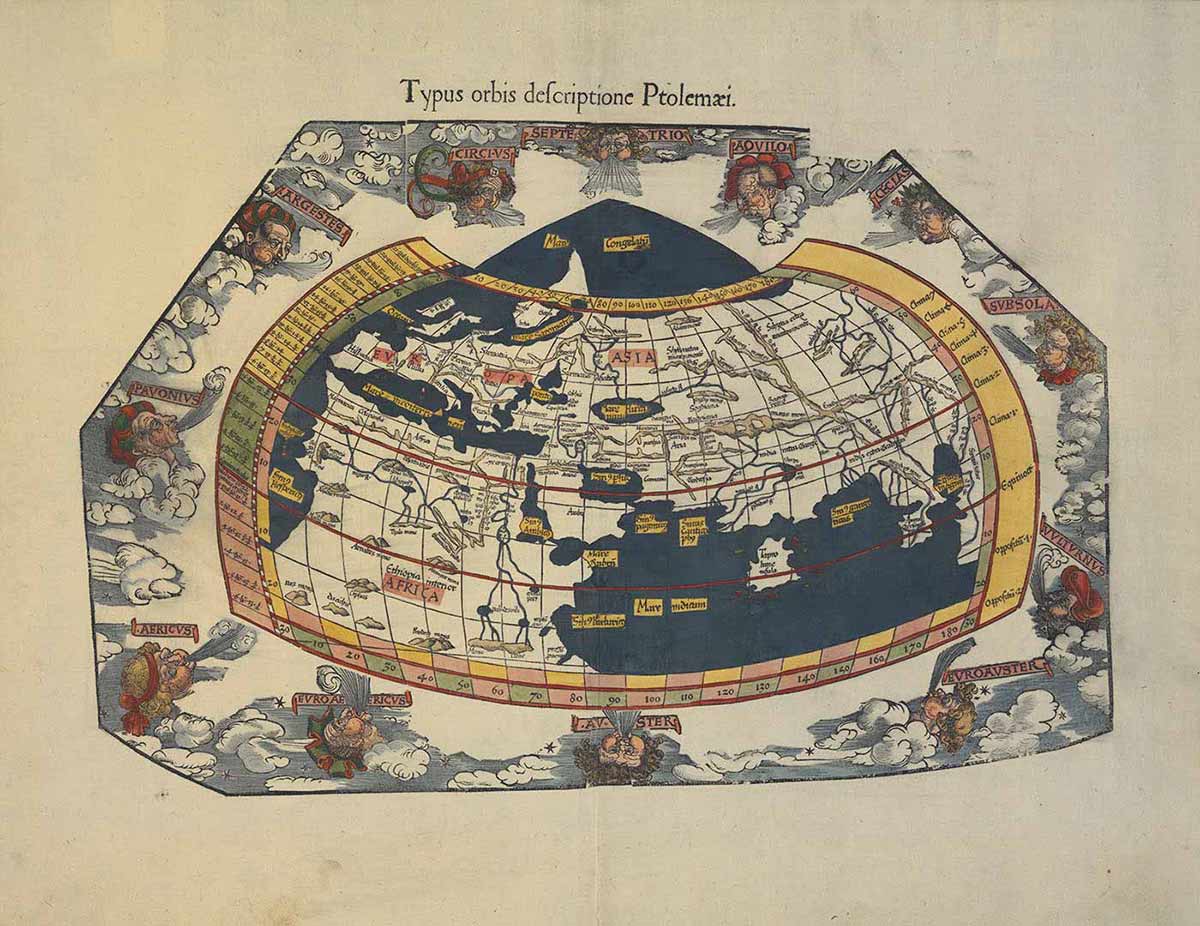

The hand-coloured map Typus orbis descriptione Ptolemaei (World map according to Ptolemy), represents Ptolemy's mid-second century world map. Produced in 1541 by Gaspar Treschel, it is significant for its role in perpetuating the idea of a Great South Land. It represents European knowledge of world geography prior to the Age of Discovery in the 15th to 17th centuries.

Ptolemy's map uses a north-south orientation and latitude and longitude coordinates, both now standard features of Western maps.

The map is decorated with 12 'wind heads', each one named for the direction from which it blows. Although it is supposed to represent 180 degrees east and west, the map actually shows only 105 degrees and so made the European and Asian land masses occupy a disproportionally large part of the globe.

Christopher Columbus used a similar Ptolemaic world map to argue that China could be reached by sailing west. His discovery of the Americas revealed a continent entirely unsuspected by Ptolemy.

Antipodean monsters

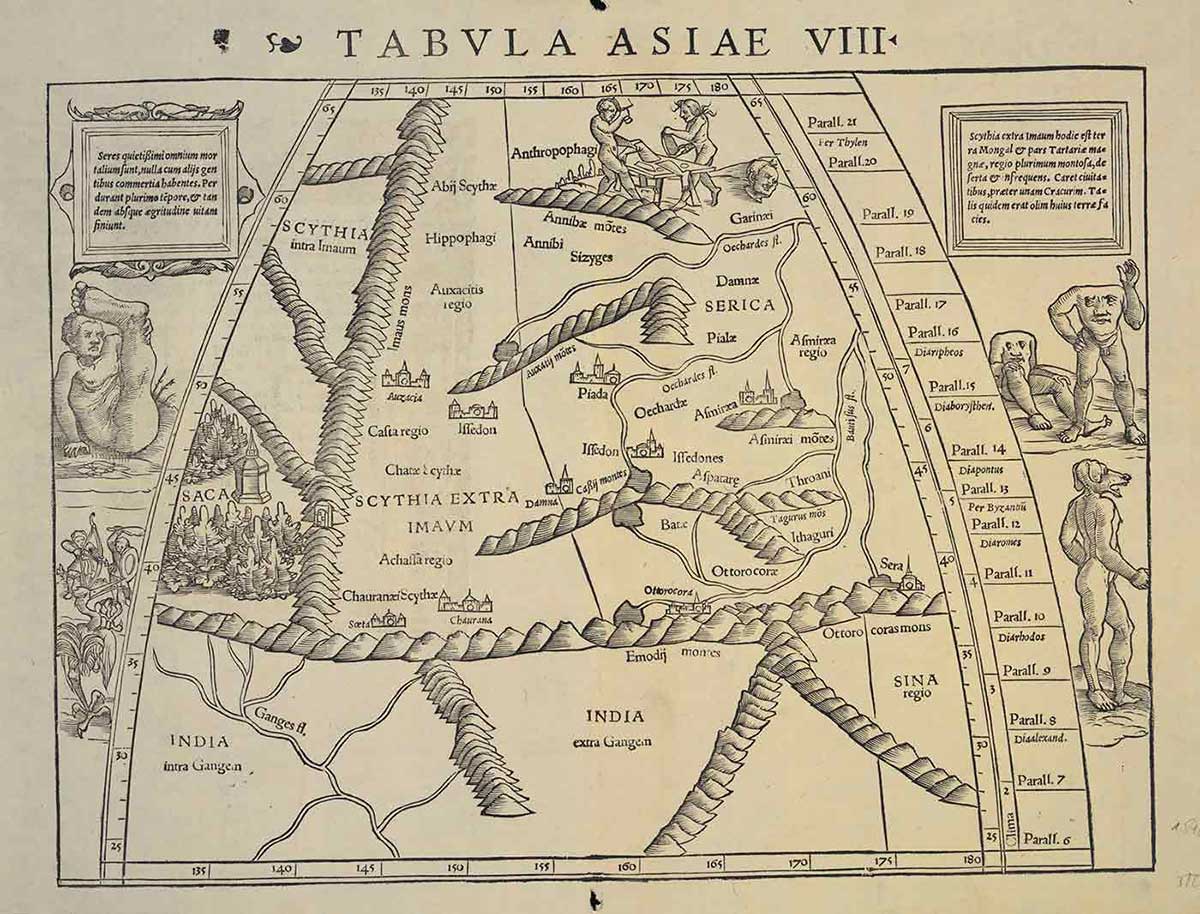

The Tabula Asiae VIII map (Map of India and Central Asia No. 8) represents the region of Scythia, in Central Asia, as it was understood at the height of the Roman Empire.

This double-page woodcut copy was published in the first edition of Sebastian Münster's atlas, the Geographia Universalis, Vetus et Nova (Universal Geography, Old and New), in 1540. Münster was skilled in ancient languages, mathematics and cartography and sought to represent the work of Ptolemy in an accurate, newly translated edition.

This map is decorated in the margins with images of Antipodean monsters, and is significant for its ability to demonstrate the survival of ancient conceptions about the world, including the existence of a monster-filled Great South Land.

These ideas remained current in the 16th century, until improved navigation and a greater reliance on empirical evidence began to challenge older beliefs.

Münster's map of India and Central Asia combines classical and medieval representations of the world, with the monsters long thought to lurk beyond Christendom decorating a Ptolemaic map.

Münster has borrowed from Pliny the elder (23–79 AD), Hans Burgkmair the elder (1473–1531) and Giovanni Botero around 1544–1617) to provide 'ethnographic' details for the monsters his map.

In his Natural History of the World Pliny wrote:

In India there is a kind of men with heads like dogs who in lieu of speech use to bark. Likewise there is a kind of people named monoscelli that have but one leg apiece. In the hottest season of Summer they lie along their back and defend themselves with their foot against the Sunnes heat.

In 1508 Burgkmair produced a two-metre long multi-woodblock frieze featuring images of the natives of the coast of Africa and India. They are now referred to as Burgkmair's 'Prodigies'.

Although the Burgkmair originals are lost, Botero reproduced a number of these images in his Le relationi universali. The images include anthropophagi, or cannibals, men whose heads grow beneath their shoulders and men with the heads of other creatures including dogs and serpents.

Hope for a second America

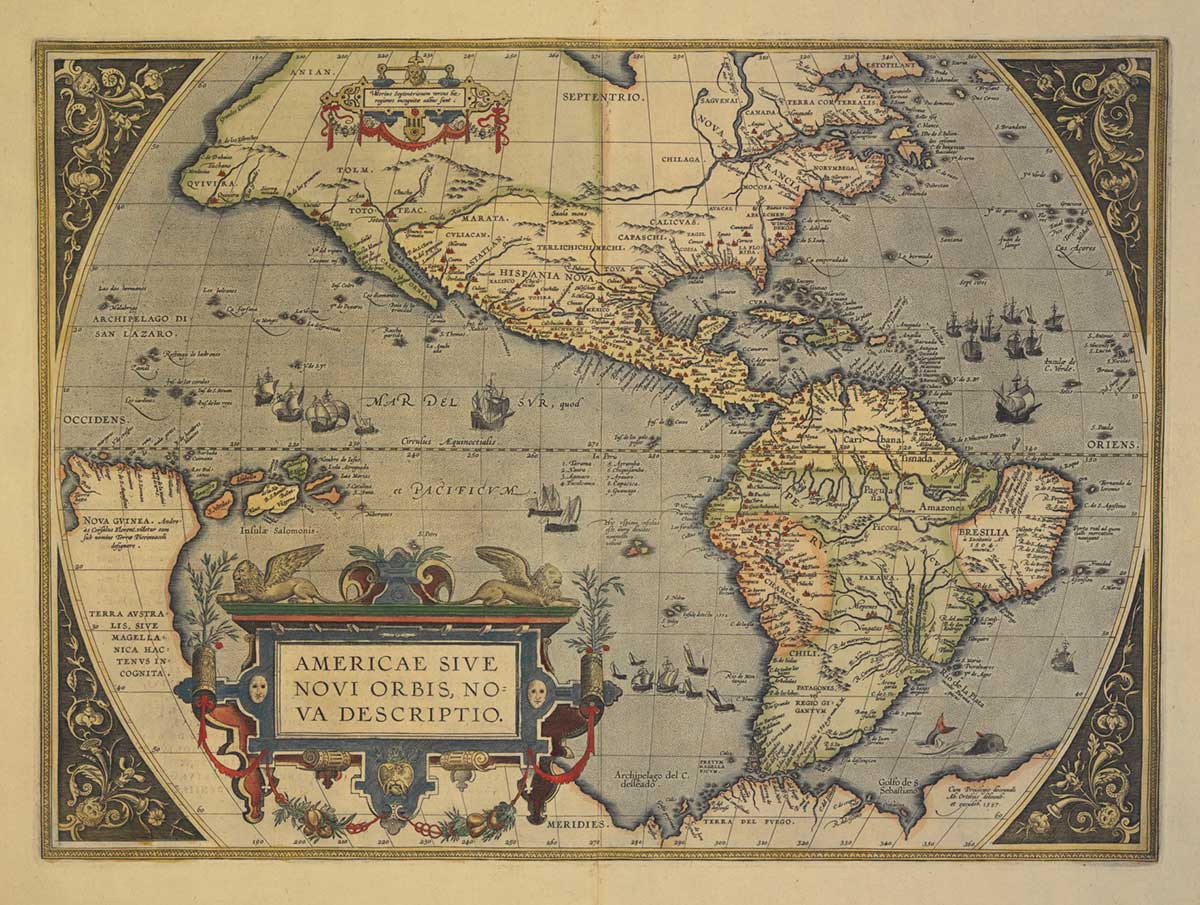

The map Americae sive novi orbis nova descriptio (America, or a description of the new world) is a 1612 edition of the third state map of America by Abraham Ortelius. It was first printed in the 1587 edition of his atlas, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World).

Considered the most accurate map of the Americas then available, it marks the emergence of a new generation of maps based on first-hand observations rather than continued reliance on classical models.

The Great South Land was reputed to be a second America and the hope of discovering it lay behind Cook's voyages to the Pacific. His voyages resulted in the claiming and mapping of Australia's east coast, and ultimately, the colonisation of Australia by the British.

Opening the Pacific

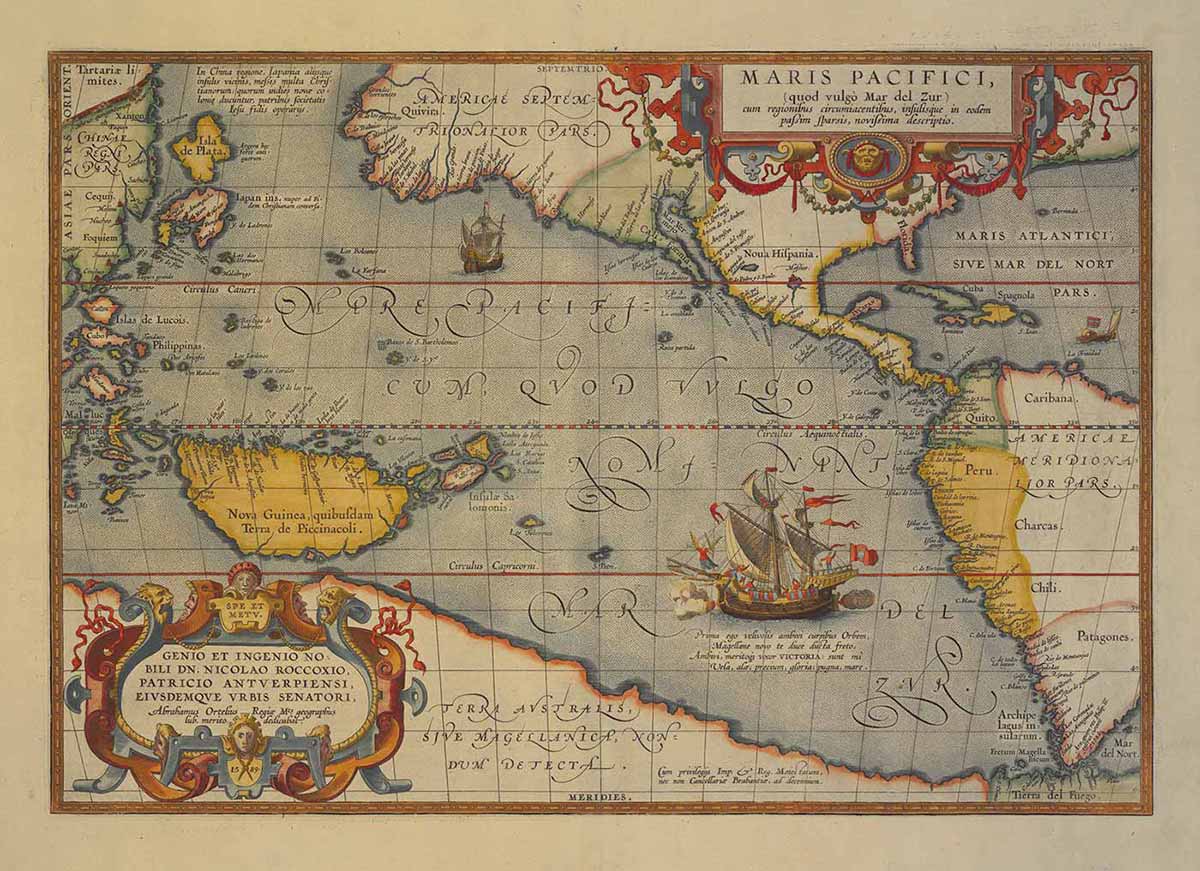

Maris Pacifici was the first printed map of the Pacific. It was first engraved in 1589 for inclusion in the 1590 edition of Abraham Ortelius' atlas Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World). This hand-coloured edition was printed in Antwerp in 1595.

Maris Pacifici quod vulgo Mar del Zur (Pacific Ocean, commonly known as the South Sea) reveals the limited knowledge the region gained from Ferdinand Magellan's (1480–1521) voyage across the Pacific in search of new route to the Indies in 1519 and subsequent voyages up the west coast of the Americas.

The ship shown between the coast of South America and a huge New Guinea is the Victoria, Magellan's flagship and the first vessel to circumnavigate the globe. The ship is shown flying the Spanish flag and with cannons firing. On her bow an angel, representing the spread of Christianity, points the way forward with one hand and holds a martyr's palm in the other.

In 1519 Magellan sailed from Seville, Spain, with five ships and 239 men to find a western route to the spice-rich Indies. They discovered the Straits of Magellan between the tip of South America and Tierra del Fuego, and continued westward across the Pacific to reach the Philippines in 1521. There, during a fight on Mactan on 27 April 1521, Magellan was killed.

The following year on 8 September, 1522, 18 crew under Captain Juan Sebastian del Cano (around 1476–1526) limped into Seville in the Victoria. The sole survivors of those who had sailed across the Pacific with Magellan, they had completed the first recorded circumnavigation of the globe, but at a terrible cost in men and ships. Antonio Pigafetta (1485–1534/5) recorded the horrendous conditions on board:

We ate biscuit, which was no longer biscuit but powder swarming with worms ... [which] stank strongly of the urine of rats. We drank yellow water that had been putrid for many days. We also ate some ox hides that covered the top of the mainyard to prevent the yard from chafing the shrouds ... Rats were sold for one-half ducado apiece, and even then we could not get them.

When Cook embarked on the first of his three Pacific voyages in 1768, he aimed to chart the southern and northern Pacific, still unknown nearly 250 years after Magellan's expedition.

In our collection