The National Museum of Australia's collection of objects related to the Burke and Wills expedition include a water bottle which belonged to Burke and a breastplate awarded to the Aboriginal people who came to the explorers' assistance.

Victorian Exploring Expedition

The Victorian Exploring Expedition, usually known as the Burke and Wills expedition, remains one of the most celebrated journeys of the 'heroic era' of Australian land exploration.

In the 1860s the colony of Victoria was flush with wealth from the gold fields and wanted to enter the field of exploration.

Supported by the Victorian Government, the Royal Society of Victoria and private citizens, the expedition hoped to be the first to cross the continent from south to north.

Robert O'Hara Burke led the expedition. Burke was an Irish-born soldier who emigrated to Melbourne in 1853. He served as a police inspector and superintendent in Victoria, and was involved in policing at the Buckland River riots in 1857.

Despite having little exploration or navigation experience, he was chosen to lead the expedition.

William John Wills was the expedition's surveyor and astronomer, and was second-in-command. Wills had arrived in Victoria in 1853, first working as a shepherd and then as an assistant to his father, a surgeon. He studied surveying and was appointed to a position at the Melbourne Observatory.

Grand departure

Described as the best equipped expedition in Australia's history, the explorers set off for the Gulf of Carpentaria carrying about 21 tonnes of equipment. The departure from Royal Park in Melbourne on 20 August 1860 was a grand public event – the expedition party was farewelled by 15,000 Victorians.

As they progressed northward, Burke found the expedition overburdened and the wagons unreliable. He feared that South Australian explorer John McDouall Stuart, who was also heading for the Gulf, might get there first.

At Menindie, Burke appointed William Wright to be in charge and left for Cooper Creek. Wright was to bring up the party and supplies. Burke grew impatient waiting for Wright to arrive and decided to leave Depot Camp 65 for the Gulf.

On 16 December 1860 Burke, Wills, Charles Gray and John King left Cooper Creek to make a dash for the northern shoreline. Burke and Wills eventually encountered salty marshes and a shifting tide, and could proceed no further. They had reached their goal, even though they could not see the open water.

Fatal return

The return journey proved fatal. Charles Gray died and the others limped back to the Cooper Creek camp only to find that rest of the depot party had departed just hours earlier. Burke and Wills died attempting to reach Mount Hopeless. King, near death, was cared for by the Yandruwandha people until a relief expedition rescued him.

When news of their disappearance reached Melbourne, four relief parties were despatched to search for them. One of the parties, led by Alfred Howitt, rescued King and buried Wills and Burke at Cooper Creek.

An expedition led by William Landsborough worked south from the Gulf through the Flinders, Gregory and Georgina River regions. Landsborough continued all the way to Melbourne and was the first European to cross the continent from north to south.

John McKinlay and his party left from Adelaide and found the flood plains of the Diamantina and travelled through northern Queensland.

Frederick Walker's party left from Rockhampton and travelled across northern Queensland. They did not find the expedition party, but these three relief parties made significant tracts of grazing land known and accessible to pastoralists. John McDouall Stuart reached the ocean and returned to Adelaide in 1863.

In 1862 Howitt returned to Cooper Creek and retrieved the remains of Burke and Wills. They lay in state at the Royal Society of Victoria in Melbourne and were viewed by over 100,000 people. Some estimated that three-quarters of the city's population watched the funeral procession in January 1863.

The tragic fate of the Burke and Wills expedition received international attention. King was given a public welcome on his return to Melbourne but never recovered from the expedition ordeal.

Victorian Exploring Expedition breastplate

This breastplate was one of three presented to the Yandruwandha people in appreciation for the assistance they gave to Burke, Wills and King.

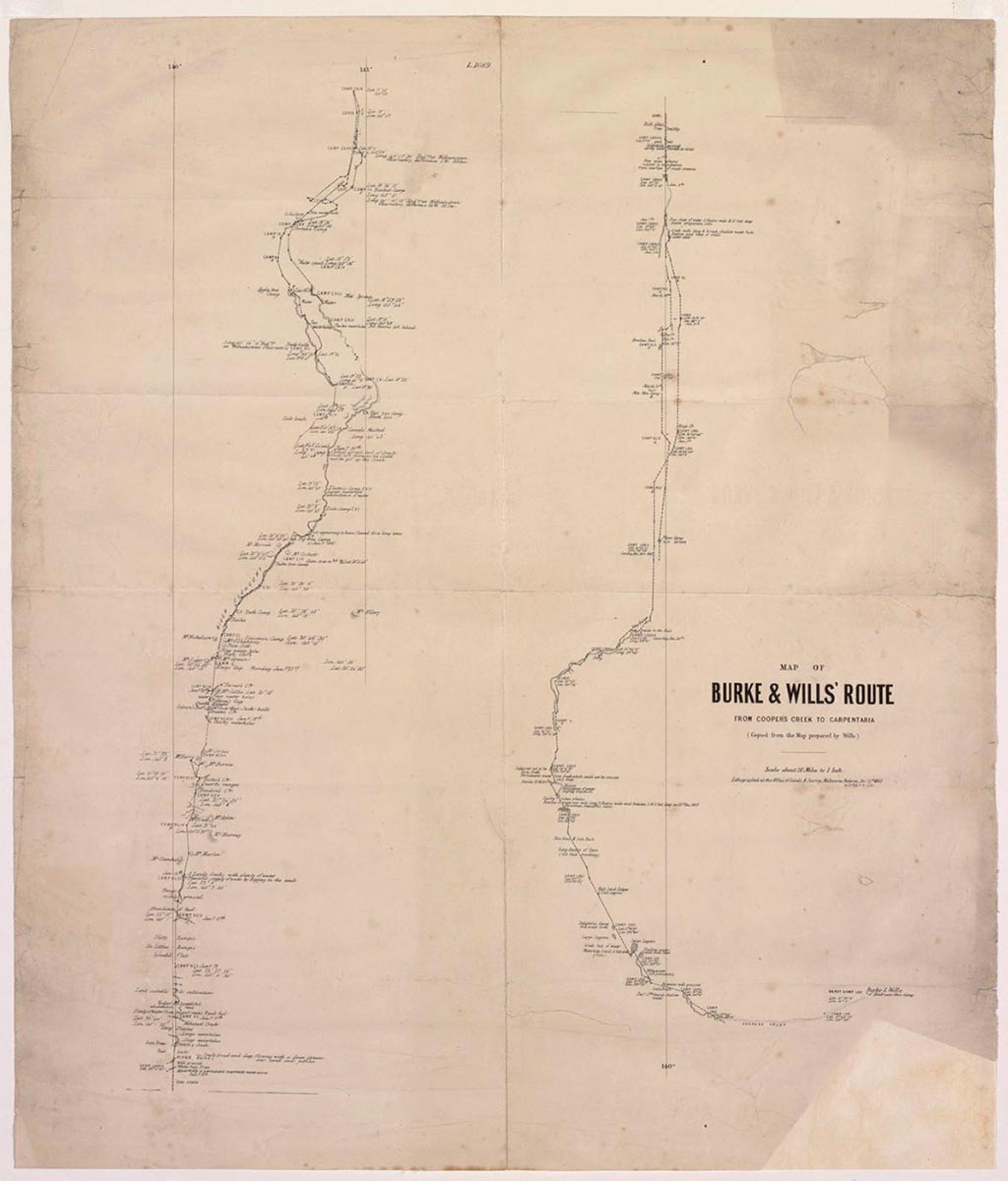

Map of the route taken by Burke and Wills

Map in black ink on white paper which is stained. The map is set in a buff-coloured mat, with has a thin clear plastic window. It is titled:

MAP OF BURKE & WILLS' ROUTE

FROM COOPER'S CREEK TO CARPENTARIA

(Copied from the map prepared by Wills.)

Scale about 20 Miles to 1 Inch.

Lithographed at the Office of Lands & Survey, Melbourne, Victoria, Nov. 25th 1861

by J. B. Philp & W. Collis.

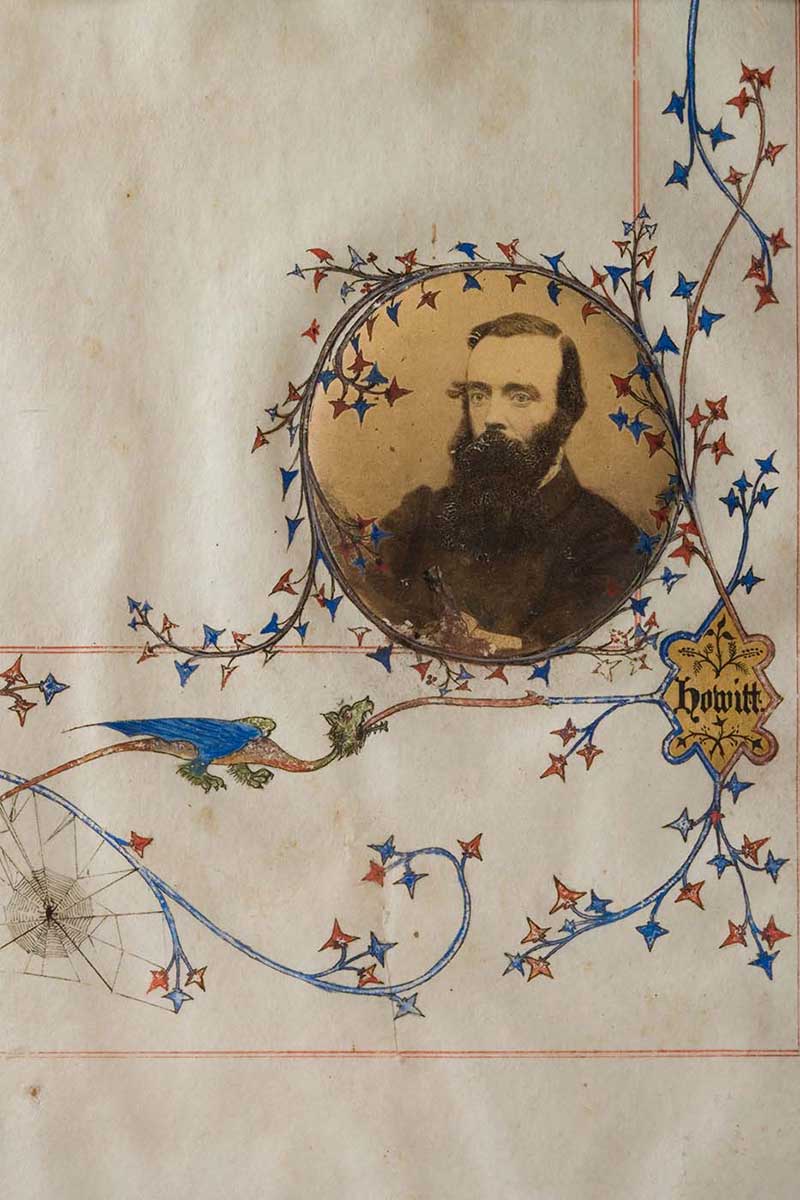

Ambrose Kyte illuminated address

A framed manuscript, written in black ink and coloured paints recognising Ambrose Kyte's support of the Victorian Exploring Expedition.

The manuscript features two rondels housing albumen print photographs of Kyte (left) and Burke (right). It is housed in an elaborate, carved timber, glazed frame which features the Australian coat of arms on the top.

The illumination was presented to Kyte by the Governor of Victoria, Sir Henry Barkly, on behalf of the Victorian Exploration Committee, on 21 January 1863, in recognition of Kyte's support of the Burke and Wills expedition.

In 1858 Kyte had donated £1000 towards the fit-out of the expedition. This enabled the committee to raise further funds required for the expedition.

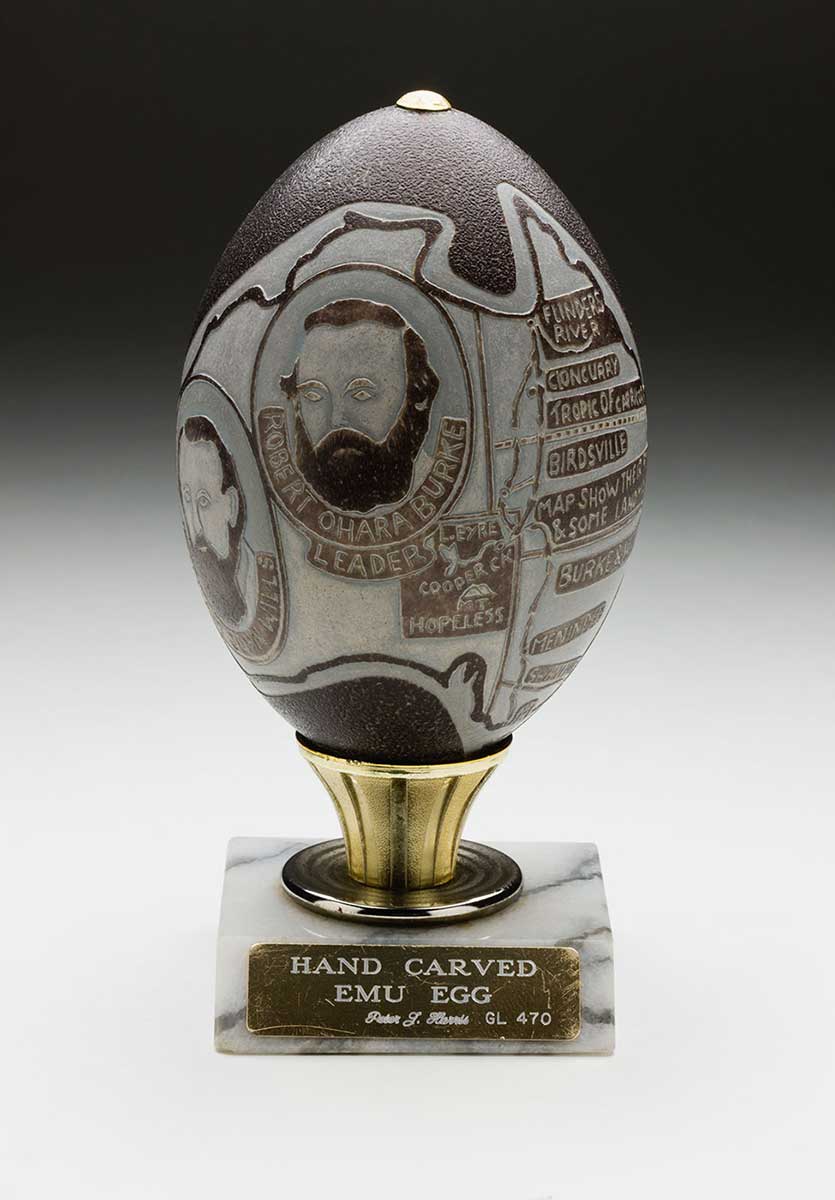

Carved and mounted emu egg

The egg, carved by craftsman Peter Harris, depicts a map of the journey of Burke and Wills.

The egg rests on a marble base with a plaque with gold lettering. The engraved text reads 'HAND CARVED / EMU EGG / Peter J. Harris GL 470'.

Burke and Wills have been the subject of art, craft and popular media since the outset of their journey. Harris has carved two eggs relating to Burke and Wills. They display his interest in local and national history as his home in Lake Cargelligo, New South Wales lies on the explorers’ route.

Emu egg carving has its origins from the 1930s when it was first taken up by Aboriginal people. Harris’ compositions reflect the style of these early carvers. He is regarded as one of the most skilled contemporary emu egg carvers.

In our collection