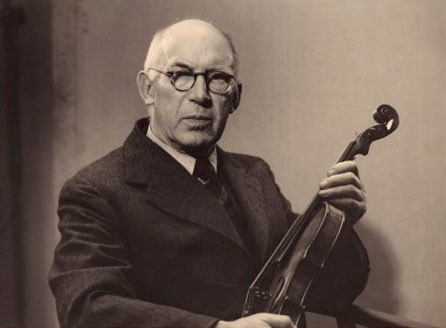

Arthur Edward Smith (1880–1978) is widely regarded as the most important violin maker in Australia. The National Museum holds a quartet put together by Smith's daughter Ruth and her husband Ernest Llewellyn.

Gifts from a golden period

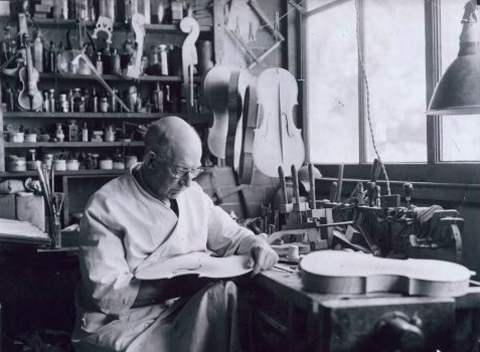

Smith handcrafted more than 200 instruments in his Sydney workshop.

The cello, viola and two violins in the Museum's collection are from Smith's 'golden period', from the 1940s to mid-1950s. They have changed little since they were made.

These instruments are played on special occasions under the guidance of the Museum's conservators.

Quality craftsmanship

Smith was born in England and trained as an engineer before he joined an antique and musical instruments firm.

Believing his opportunities as a violin maker in England were limited, he travelled to Melbourne and San Francisco. He returned to Australia and set up a shop in Sydney in the 1910s. Smith's workshop in Hunter Street soon established a reputation for repairing and selling quality stringed instruments.

Illustrious musicians including Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern visited Smith's workshop. This allowed him to model instruments on the work of European masters such as Stradivari.

Smith experimented with Australian timbers but preferred to use those from Europe. He set up a strings factory after a wartime shortage and produced his own varnish, which remains a family secret.

Quartet assembled

Smith made about 170 violins, 40 violas and three cellos in his career.

The instruments in the Museum's quartet belonged to various owners until they were assembled by the Llewellyns and bought by the Australian Government in 1978. Ernest Llewellyn was director of the Canberra School of Music, where Llewellyn Hall now bears his name.

The 1946 violin is modelled on the 'Maurin' Stradivarius. This instrument was originally made for Mrs Swinburne Johnson, who gave lessons under the name of Madame Rolunde.

The 1954 violin is modelled on the 'Alard' Stradivarius and was given personally by Ernest Llewellyn to ensure the high standard of the quartet.

The viola made in 1952 was modelled on Brescian lines, meaning its construction follows the ideas of early Italian makers. It was originally made for Priscilla Kennedy and this instrument came to the quartet through a swap or an exchange.

The cello, made in 1953, is modelled on the 'Haussmann' Stradivarius. Smith studied the Stradivarius original which came to him for repairs while Edmund Kurtz was touring Australia. Kurtz played the Smith cello at several venues on his Australian tour as he considered the Smith to have comparable qualities to the Stradivarius.

Conservation challenges

Functioning objects in a museum collection challenge curators and conservators and the AE Smith quartet is no exception.

Conservator Robin Tait said debate over whether to play or preserve is interesting, though the National Museum believes it has adopted a position of compromise.

Robert Barclay, a conservator from the Canadian Conservation Institute calls it 'display and occasional use'. The instruments are played occasionally, and displayed and stored in controlled conditions. Barclay says:

the quartet is still celebrated for its cultural value and pedigree and the conservation practices reflect concern for historical value and integrity. This compromise also highlights the fact that 'to play or to preserve' is by no means an exclusive choice.

The historical integrity of the instruments has been retained. Two small repairs on the cello were completed by members of AE Smith's family. His daughter Kitty Smith and grandson Daffyd Llewellyn both took on the trade.

Smith made these instruments at a time in history when he was able to benefit from the lessons of the early makers, the past innovations and the changes to violin construction.

His instruments have not been altered and were constructed with a craftsmanship that has ensured that no major interventive repairs have been required. His original varnish exists on all the instruments in the National Museum's quartet.

Playing to new audiences

The Museum's approach to conservation balances the historical integrity and physical preservation of the instruments with their need to be played, as functioning objects.

The pieces in the quartet were so finely constructed that they have needed only minor repairs. They have not been altered and Smith's original varnish remains on each.

The Museum has worked with top professional musicians so that audiences can experience the continuing joy of hearing music produced by Smith's instruments.

Concerts have featured the Canberra Symphony Orchestra.