Marking 100 years since Edward's royal tour

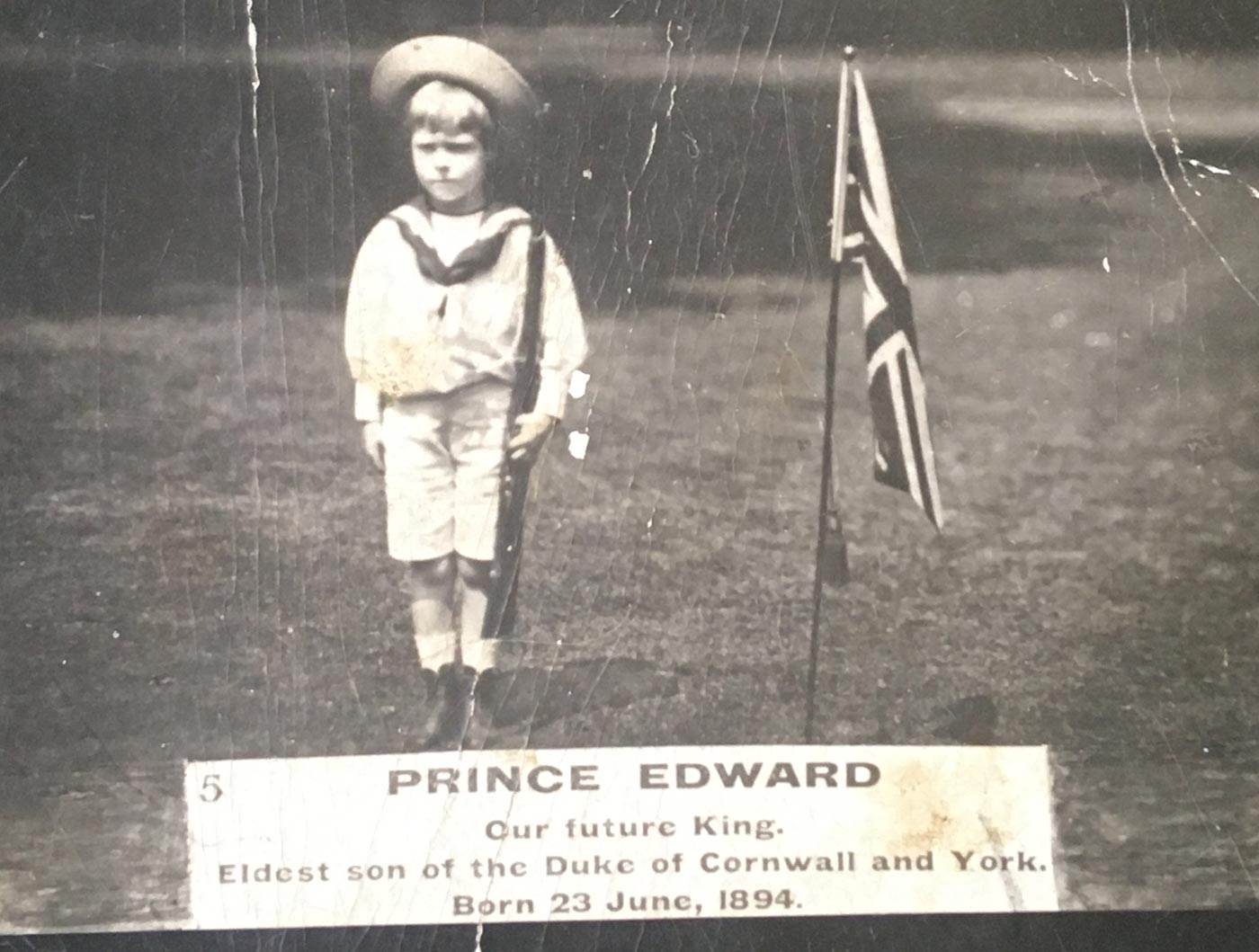

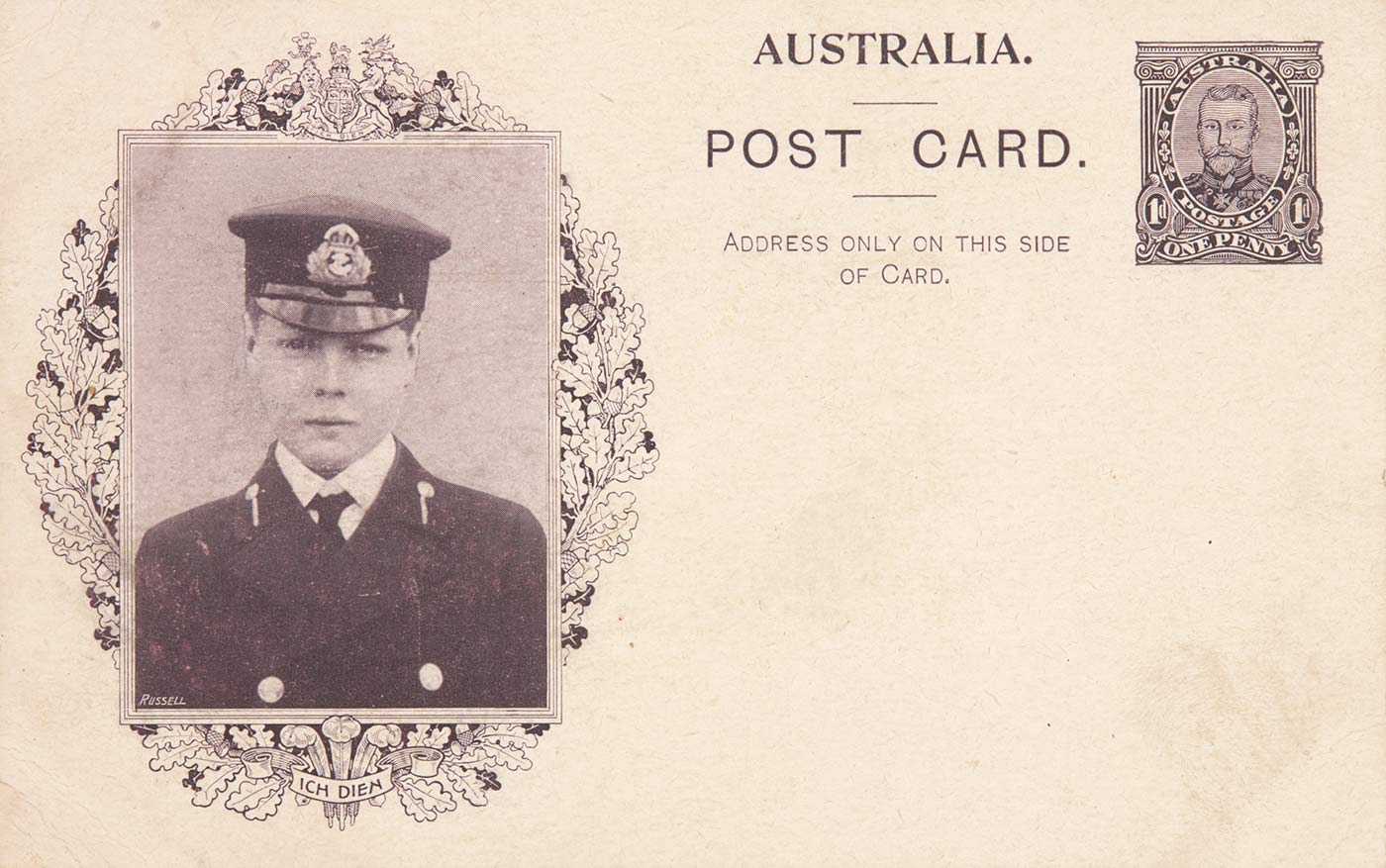

Prince Edward’s arrival in Australia had been long anticipated. Before the outbreak of the First World War, King George V had planned to send his young sons on a far-reaching tour of the British Empire. While still a child, Edward had attracted global attention as the heir to the throne. This only increased after he became the Prince of Wales, aged 16 in 1911.

Royal tours were an instrument of policy to rally popular support for imperialism and calm nationalistic sentiment. Edward especially endeared himself to the Dominion troops during wartime by his eagerness to serve on the frontline. By the end of the war in 1918, he had never been more popular.

Dominion tours

Nonetheless, the King’s 26-year-old son was more interested in romance and racing than preparing for his future duties.

The royal household and the British Government hoped that an extended series of dominion tours would train him for public life, as well as reinforce collective pride in the Allied forces’ victory.

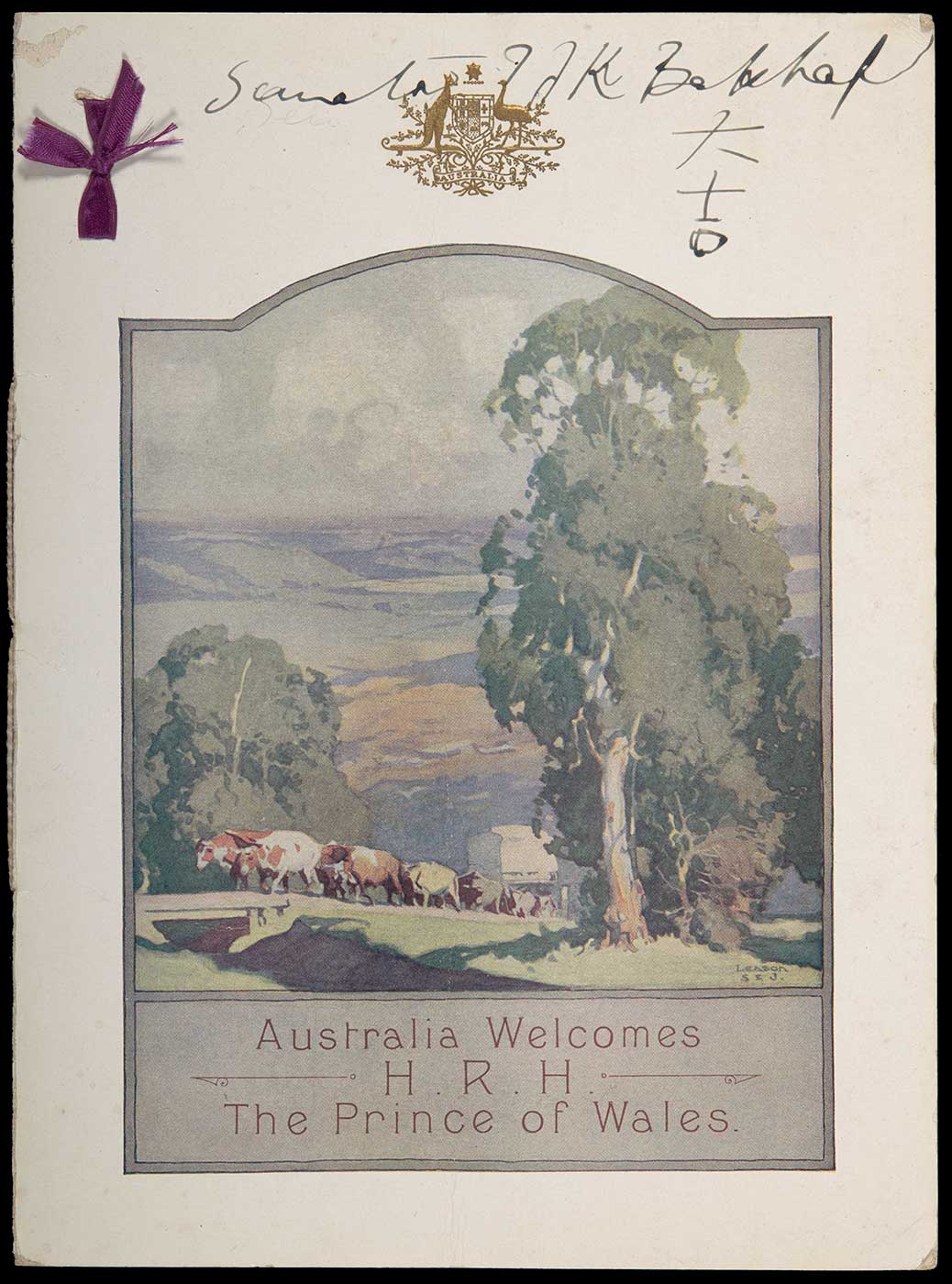

Dispatched first to Canada in 1919, Edward arrived in Australia aboard HMS Renown to great fanfare in May 1920.

Over the following three months he and his entourage visited over 100 regional and urban destinations on a 14,000-kilometre round trip.

A modern prince

Australians were eager to lay eyes on the man who would one day be King, but the remarkable appeal of this rather ordinary man ran even deeper.

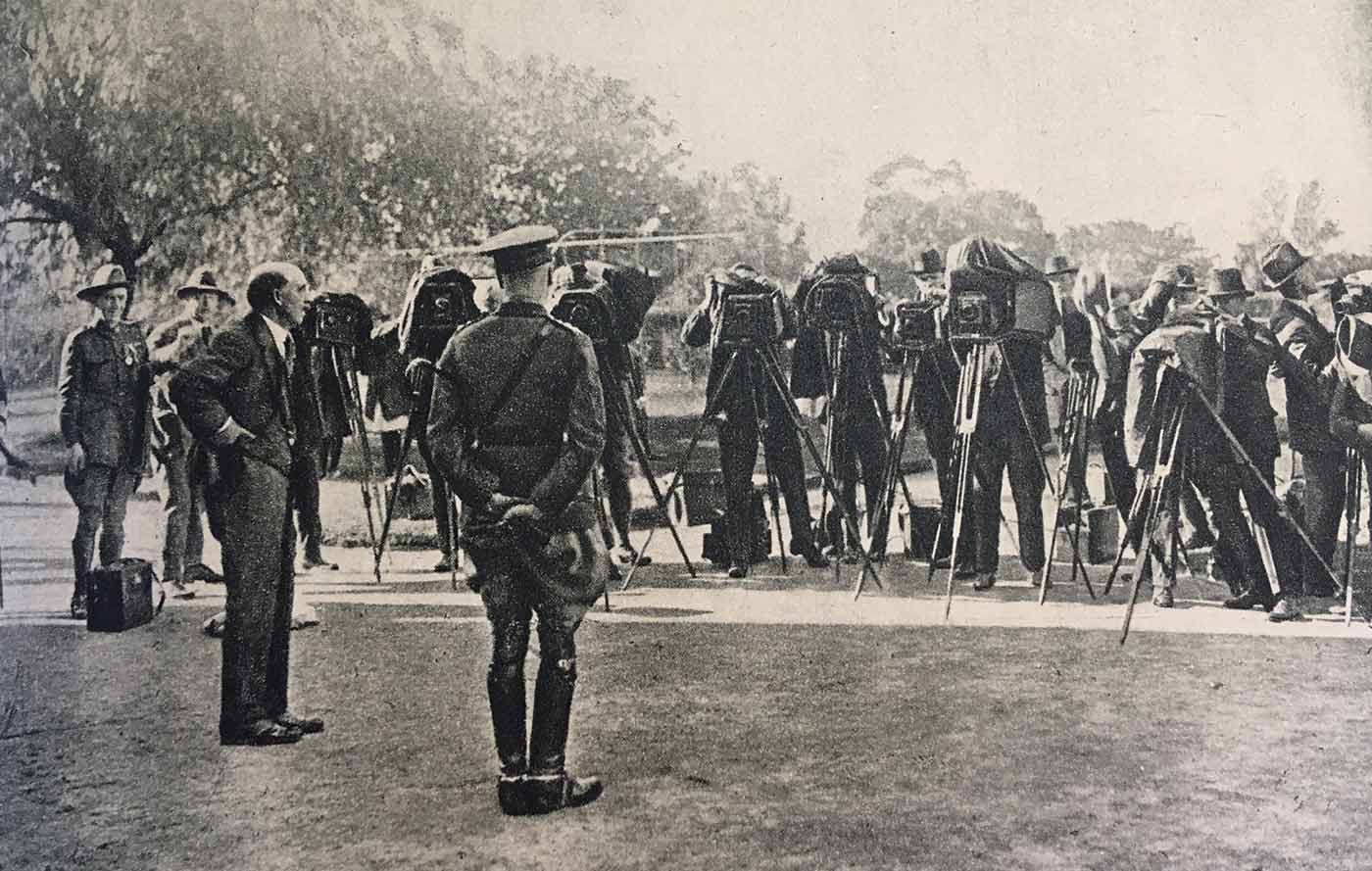

By 1920 the monarchy’s public façade was changing. Edward’s public life coincided with global advances in visual technology and growing public interest in the private lives of ‘celebrities’.

The press applauded his love for modernity, his taste for parties and flirtations, fashionable clothes, and new aviation and automobile technologies. He also had a reputation for caring about poverty and oppression.

Many anglophones living across the dominions hoped this captivating royal would steer the interwar monarchy towards a bright and progressive future.

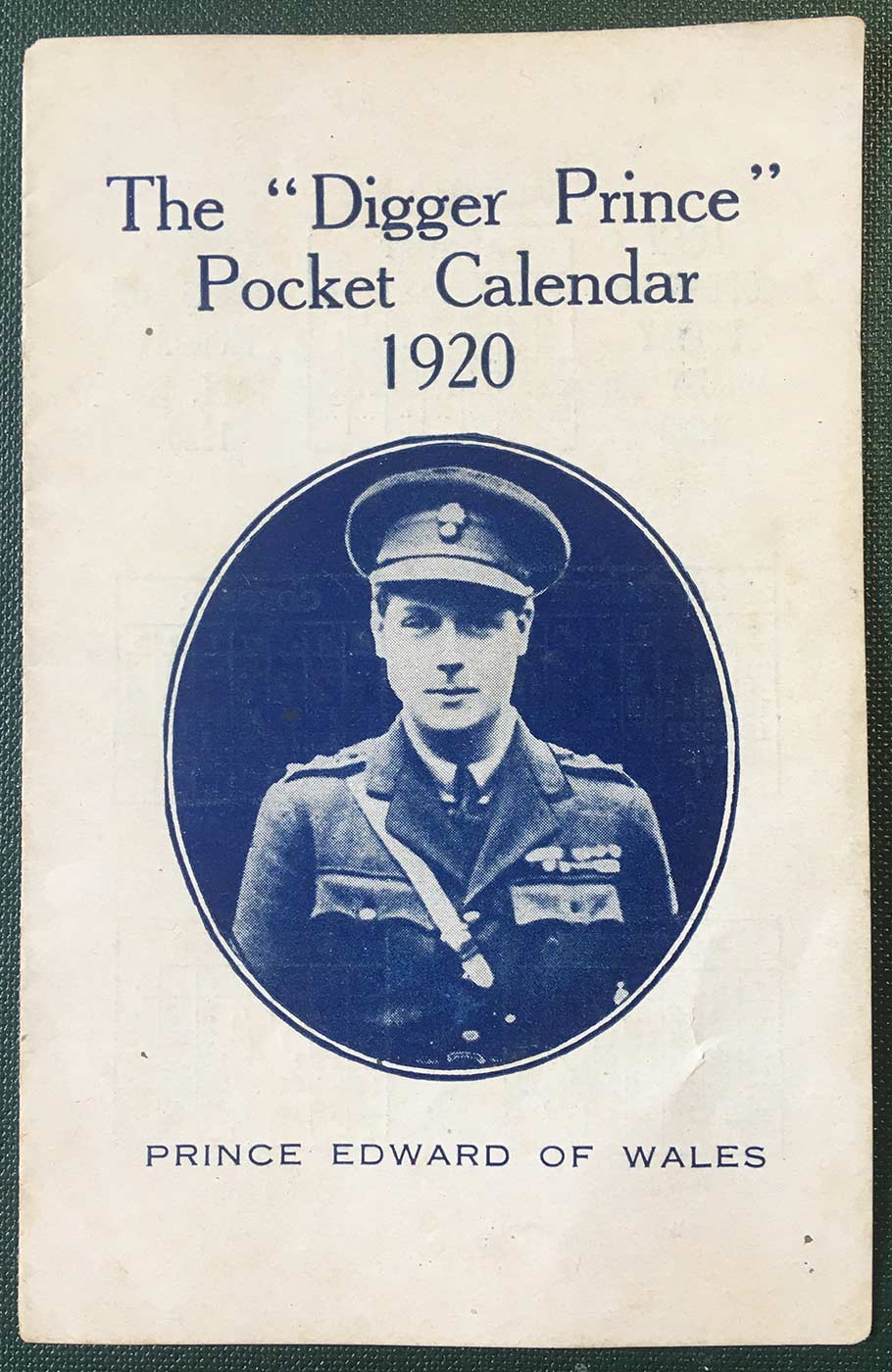

The Digger Prince

As the dominions reeled in the aftermath of war and the social and economic cost of the horror was better understood, the Prince’s supposedly liberal outlook ensured the tour’s success.

For many, his arrival confirmed that Britain had recognised the dominions’ immense sacrifice and contribution to the war effort.

Edward’s reported dislike of fuss, snobbishness and pretension resonated with supposedly similar Australian characteristics.

Despite his limited war service, he was still hailed as a brother in arms and triumphantly nicknamed the ‘Digger Prince’.

Australian tour controversies

The tour’s management was mostly administered by Australian authorities. The scope was dauntingly vast.

After arriving in Victoria, the entourage travelled through New South Wales and Western Australia, returned east through South Australia and Tasmania, before finishing in Queensland.

The complexities of the itinerary provoked heated controversy between local, state, national and even vice-regal officials. Each state pushed its own objectives in defence, industry, migration and communications. The Prince was used to promote anything and everything from pianolas to peace loans, three-piece-suits to threshing machines.

On the other hand, administrators were also empowered to steer the itinerary clear of areas of social, religious and political controversy. Fears grew over sectarianism, workers’ rights movements and socialism, which were variously gaining traction across the country.

The conservative press, both in Australia and in Britain, reported extensively on Edward’s tour and vigorously suppressed any note of discord. Instead, a different Australia was performed for the Prince; one populated by a youthful healthy and peaceful pro-imperial population.

Tour highlights

Edward donned brown overalls to descend a goldmine in Bendigo, and smashed bottles on the hulls of Newcastle’s finest ships. In Western Australia’s ancient forests, he took an axe to a mighty jarrah at a planned settlement in Pemberton.

Heading east on the Trans-Australian railway, he hobnobbed with controversial welfare worker Daisy Bates at Ooldea, admired Tasmania's apple-cheeked schoolchildren and Queensland’s splendid racehorses.

Almost everywhere he went, the public and press enthusiasm was uncontrollable. Victory celebrations had been curbed by the devastating 1919 influenza pandemic, but by 1920 communities felt ready to mingle without fear. Perhaps many among the crowds were simply pursuing a good time, rather than a glimpse of a remote royal.

The Prince was put through repetitious theatrical welcoming rituals, kitted out in ceremonial clothing and paraded in old-fashioned forms of transport. Well-attended ‘people’s receptions’, the royal progress, race meets, balls and garden parties were all repeated with dizzying frequency.

This pageantry did have another purpose. Edward’s presence at ex-servicemen’s functions, visits to repatriation hospitals, soldier settlements and local monuments to the dead acknowledged Australia’s profound collective grief.

Overscheduled royal

Privately contemptuous of blustering officials and profoundly racist in his attitude towards Australia’s Indigenous population, the Prince tired of Australia long before the itinerary wrapped up.

Although his staff tried to force him to eat breakfast, go to bed before midnight and cut down on cigarettes, the strain of being the centre of public spectacle got the better of him on many an occasion.

First and last visit

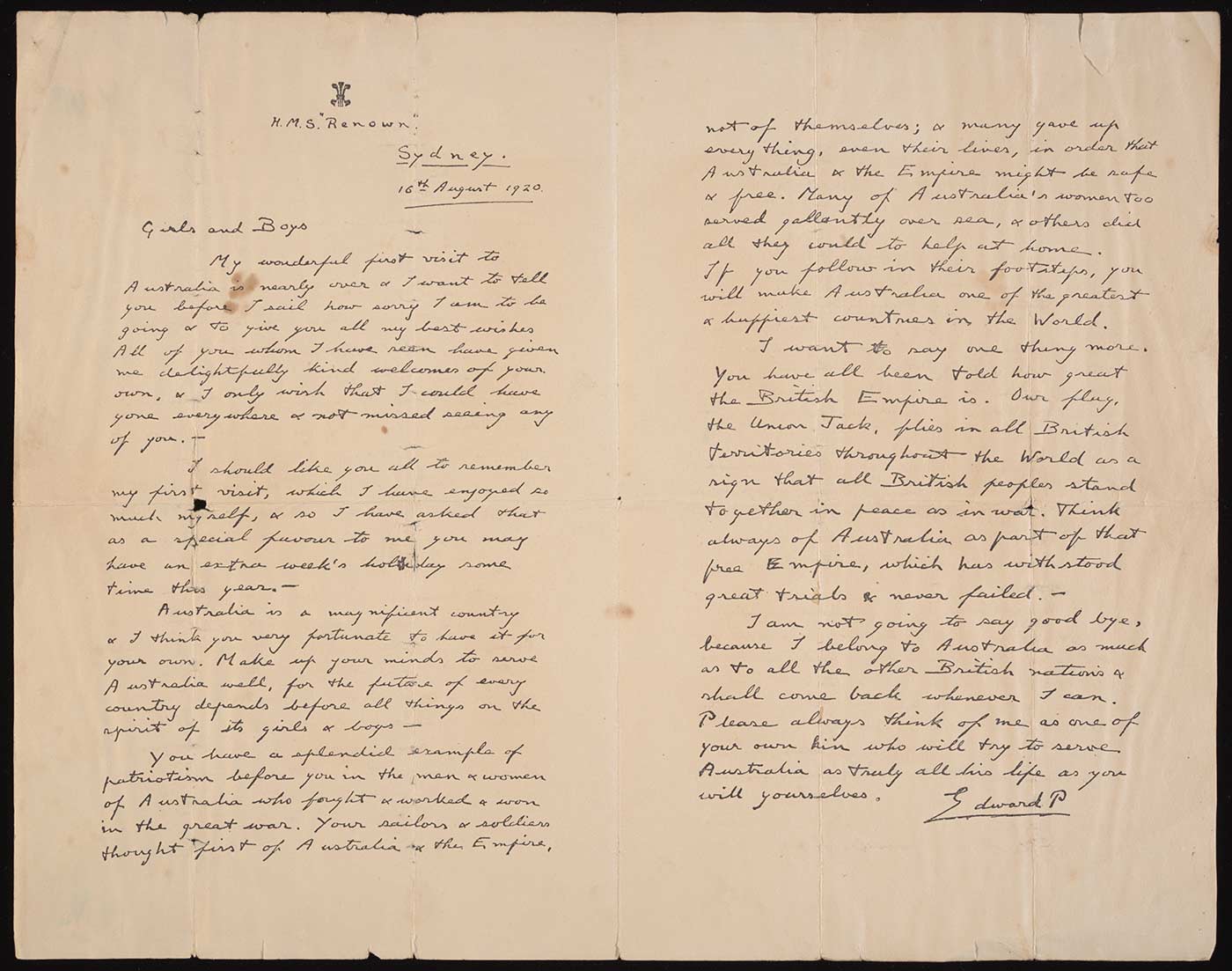

As HMS Renown sailed away in August 1920, local authorities attempted to prolong the sentimentality by minting thousands of commemorative medallions intended for the nation’s schoolchildren. Facsimiles of a patriotic letter written by the Prince at the end of the tour were also distributed through schools.

Although he pledged to ‘come back whenever I can’ and serve Australia ‘truly all his life’, the King-to-be would never return.

After briefly ascending the throne after the death of his father in 1936, he abdicated in favour of his brother Albert, the Duke of York, in 1936.