Exploring the Museum’s new Great Southern Land gallery, I’m stopped by a flat-topped case. I bend forward and peer in at a thylacine, half-curled on his side in a bath of preserving fluid, his skin flayed away to reveal sinewy muscles and tendons.

Long whiskers glint russet in the dim light and the animal’s spine curves in a peculiar kind of hump. The thylacine’s front paw pads are callused, his toenails chipped and cracked. His last steps must have been hurried, I think, not a fluid padding by but a desperate leaping away over rough ground.

On 7 September each year, Australia marks National Threatened Species Day. The date commemorates the death of the last known living thylacine, once thought to have been nicknamed Benjamin by his captors, and since found to be a she rather than a he. This thylacine passed away in 1936 in a zoo in Hobart after being locked out of its shelter overnight in the cold.

Since that sad event, the thylacine has become a widely recognised symbol of extinction. From 1996, Threatened Species Day has deployed the story of this loss to call for action to prevent the hundreds of our continent’s at-risk plant, insect, fungi and animal species suffering a similar fate.

Extinction icon

Thylacine remains have been transformed over time into relics

Standing in Great Southern Land, keeping company with the flayed thylacine, I’m reminded of my first visit to a French cathedral. I glanced into a curious window beneath an altar and was shocked to discover the bones of a diminutive, long-dead saint.

This rather bizarre association begins to make sense as I think on how the thylacine has become an extinction icon. Thylacine remains have been transformed over time into relics, akin to the sacred skeleton, material instantiations of and spiritual conduits to a reverenced, incorporeal being.

The problem with myths

Thylacine themselves have become moral lessons in the consequences of human rapaciousness. Indeed, the National Museum previously displayed the thylacine with the lovely russet whiskers in a kind of solitary shrine, a place for remembering how most European settlers' incomprehension of Australia’s unique landscapes resulted in tragic ecocide.

I can’t argue with the marketing genius of this trajectory, and goodness knows we need every tool we can muster to galvanise collective will to head off the current extinction catastrophe. But I’m troubled by the story of the thylacine, or, better, thylacines’ stories, being reduced to myths.

Is this enough to honour the species and its ancestors’ experiences over the 25 million years they roamed Earth? Is it sufficient to enable us to truly grasp and absorb what was lost from the world when thylacine were exterminated?

Surely, we need to also comprehend something of what it was to be a living thylacine, and to know this not abstractly but in a loping, yawning, nuzzling, biting, making a mess kind of way.

Thylacines in the Museum collection

The National Museum of Australia holds a wide range of thylacine material, encompassing a diversity of anatomical preparations, historical artefacts, images and artworks.

These collections reveal a long history of people trying to decide what a thylacine was, how to see it, classify it and act towards it. They can also, perhaps, particularly when considered in relation to each other, help us imagine the thylacine not as representative of something else but as, well, a thylacine.

Through our empathetic attention, these objects can further enable some of the thylacine’s world-making to continue, telling fresh stories, generating relationships and fostering new ways of being in the world.

In search of the thylacine

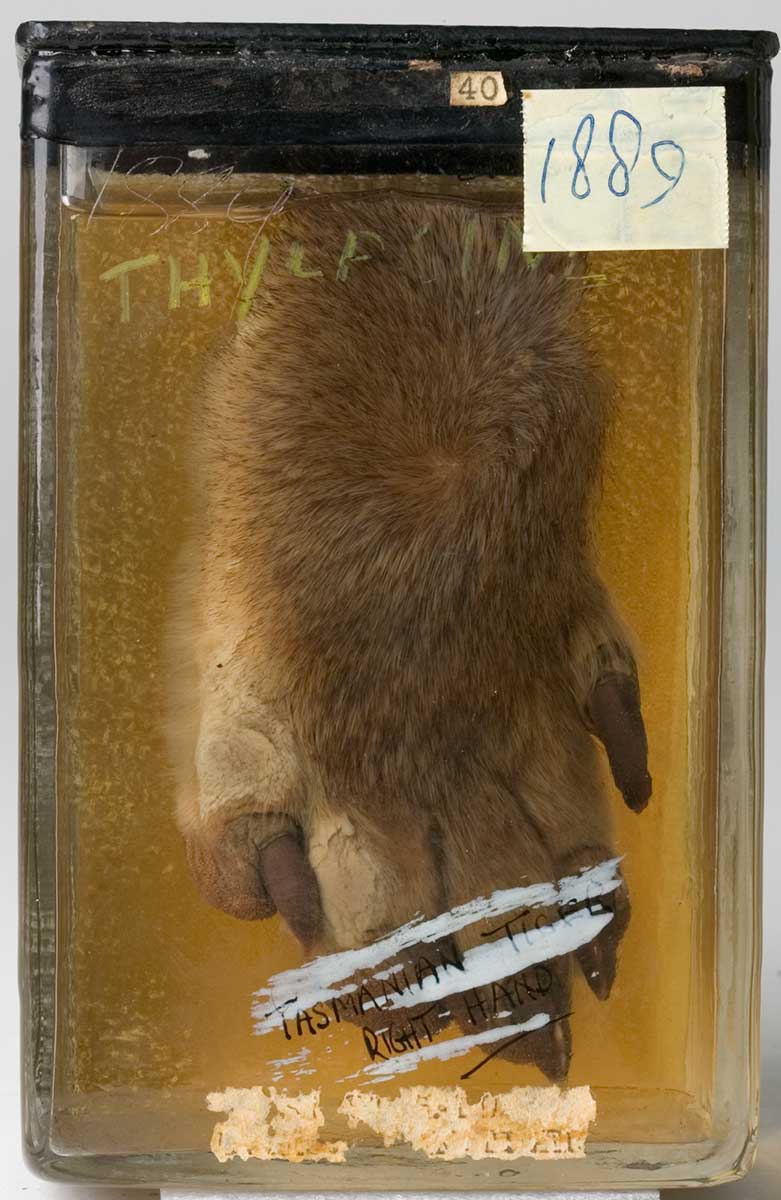

The Museum’s Australian Institute of Anatomy collection, created during the early decades of the 20th century by Melbourne orthopaedic surgeon Sir Colin MacKenzie, includes more than 30 thylacine body parts preserved in fluid, as well as a complete articulated skeleton.

Specimens in glass jars, identified as ‘pancreas’, ‘larynx/tongue’ or ‘right hand’, record MacKenzie’s invasive dismembering and his interest in laying bare the thylacine’s anatomical characteristics in order to decide and demonstrate its position in hierarchical evolutionary schemas.

MacKenzie was interested in thylacine mechanics, at the species level, rather than the marsupial’s collective or individual zoological, ecological or historical significance. He did not, consequently, record from where, when or in what manner he obtained the animals that became his specimens.

So, we know very little about each of them. The incredibly rare whole thylacine carcass with which I began this essay is part of the Institute of Anatomy collection.

His callused pads and cracked toenails help me imagine him in the shapes and textures of his territory, but I will never know exactly when he came into the world, where he liked to sleep or his individually unique pattern of stripes.

Zoo animal

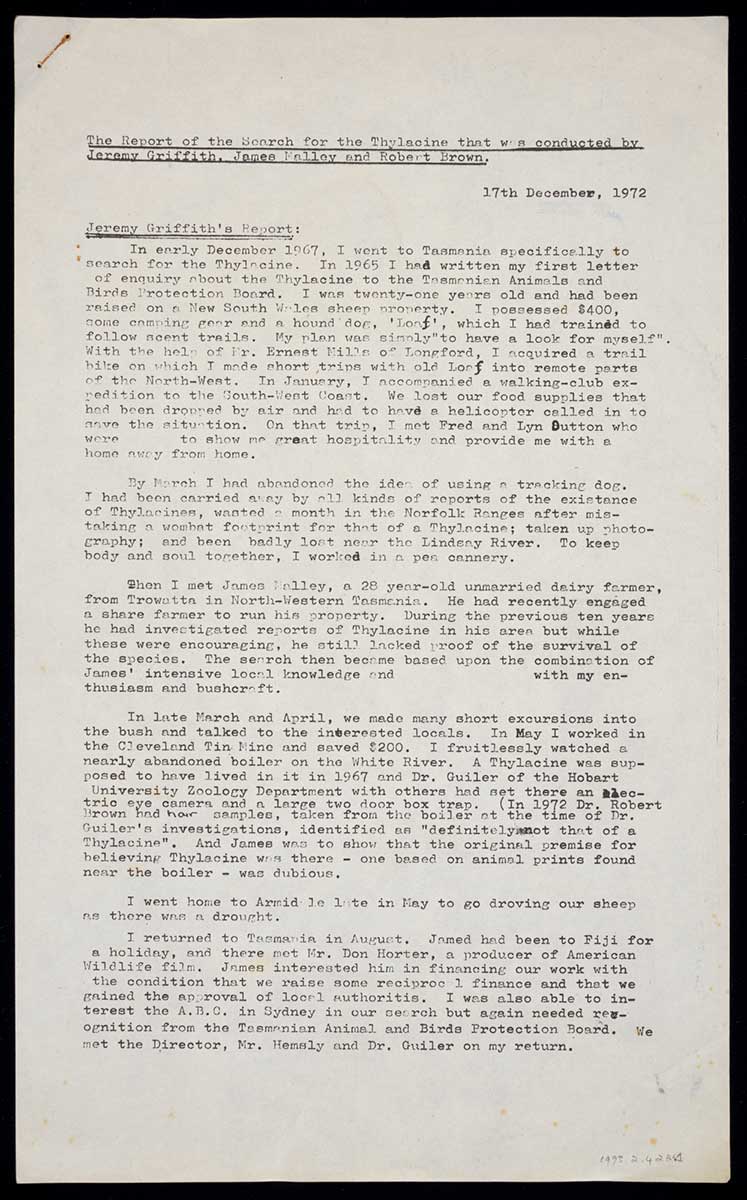

The David Seth-Smith collection at the Museum similarly lacks provenance, while revealing much about how people have perceived thylacine. The single glass lantern slide shows a solitary animal standing in an enclosure, probably at London Zoo in the early decades of the 20th century.

British zoologist Seth-Smith, who created the image, was a leading figure in the international trade in living thylacine. He may have bought the pictured individual for the European tour of his planned grand exhibition featuring exotic fauna from around the British Empire.

This thylacine, to my eye, looks quietly subdued by his brick and wire walls. Is he or she dreaming, perhaps, of the universe of grass, rock and sky from where he came? Or simply pausing after depositing the pile of scat you can make out, blurred, at the back of the enclosure?

‘Tasmanian Devil’

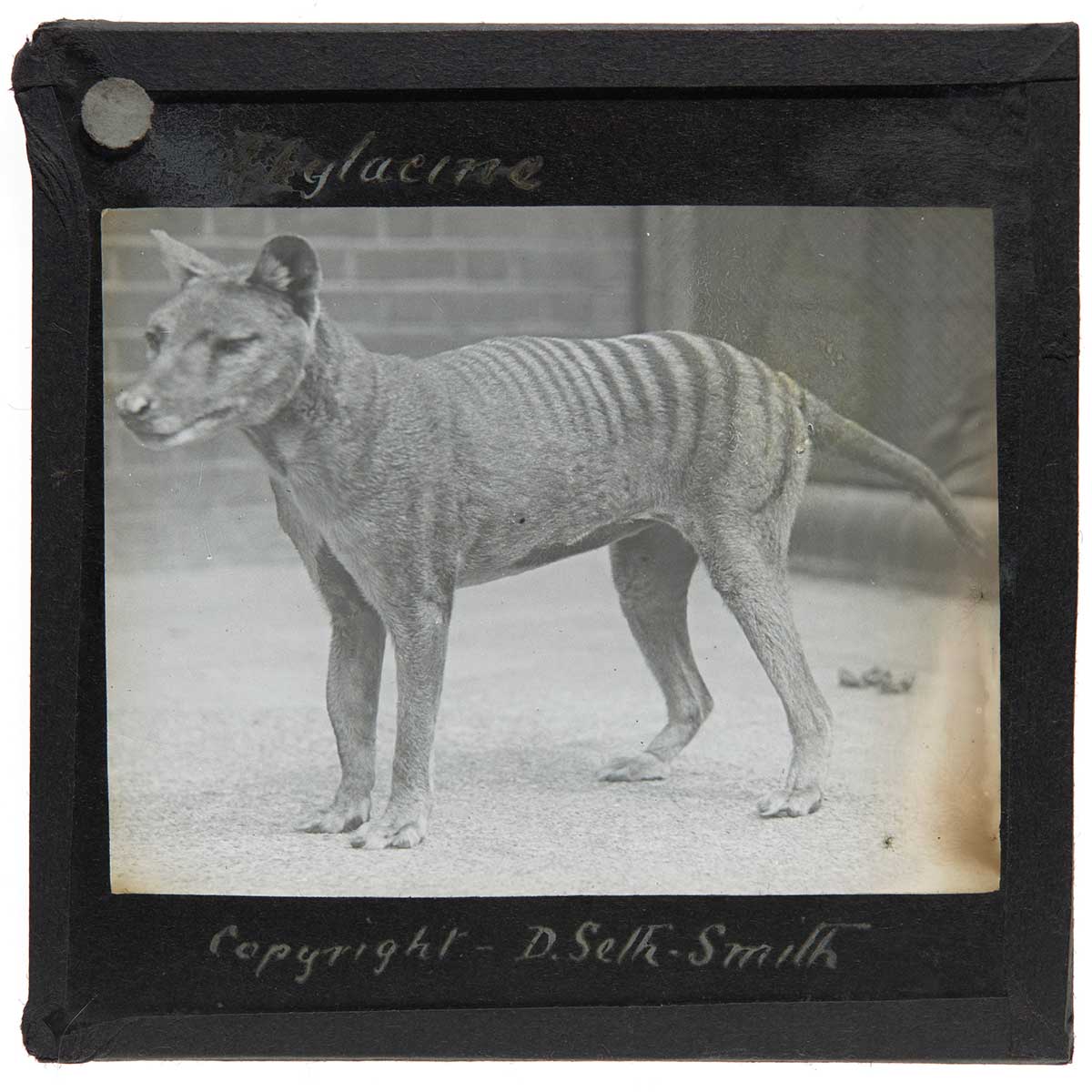

While Seth-Smith’s photograph captures a thylacine, watchful but quiet, other objects created in the same period suggest popular understandings of the species as an aggressive and dangerous hunter. Among the Museum’s extensive postcard collections, one by the Sydney-based photography studio Kerry & Co shows a snarling thylacine poised on the edge of a rocky precipice.

A reproduced drawing of what is almost certainly a taxidermied specimen in an imaginary landscape, the postcard gives the thylacine a wild eye and pointed tongue and proclaims it a ‘Tasmanian Devil’.

Hunted to extinction

Colonial British settlers and hunters lived this 'Tasmanian Devil' idea of the thylacine and responded to it as any good Christian army would when meeting demonic forces.

When colonists first arrived on Iutruwita (Tasmania) and began seizing land for sheep and cattle, around 5,000 thylacines lived among the rich grasslands and along the edges of forested areas. Read Carol Freeman's article on European impressions of the thylacine

By the 1930s thylacines were gone. Decimated through habitat loss and disease, they were hunted to extinction in the conviction – almost certainly wildly exaggerated – that they preyed on stock. The killing was catalysed by commercial and government bounty schemes.

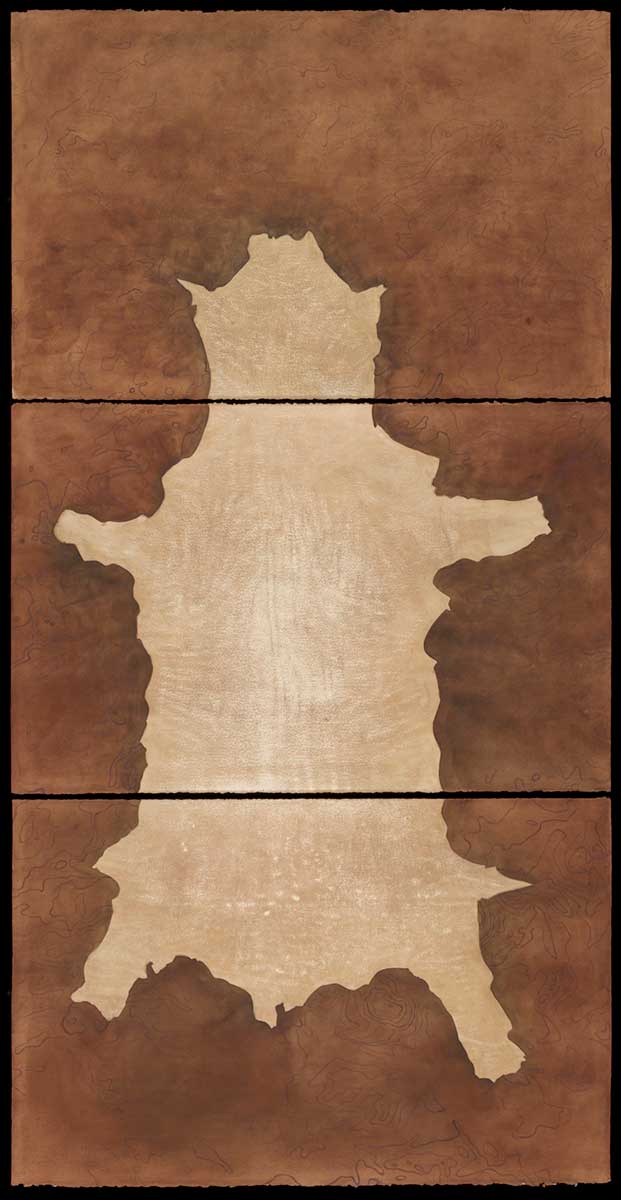

Thylacine pelts

In the Museum’s collection, two thylacine pelts record this sad story. One comes from an animal likely shot in 1930 by surveyor Charles Selby Wilson in the Pieman River–Zeehan area of north-west Tasmania. The last authenticated killing of a wild thylacine was in September that same year, so this pelt probably comes from one of the last individuals to roam the forests.

At around the same time that this thylacine died, his or her home range was proposed as a reserve protecting the species, but by then it was all too late.

The Pieman River–Zeehan area pelt is worn and faded, missing its tail and paws, in the process of becoming something more like a floor mat than the hide of a living animal.

It’s her paws that seem so almost alive

The second pelt held by the Museum remains closer to the individual of which it was once a part. Dense grey-brown fur, no doubt soft to the touch, invites me to imagine the female at home in Tasmania’s damp climate, dark stripes enabling a blending with stands of waving kangaroo grass.

But it’s her paws that seem so almost alive, each reminiscent of a delicate puppy hand that might sit gently on my palm. Again, we don’t know where this thylacine lived, only that her skin became part of New Zealand artist Archibald Campbell Robertson’s collection, probably in 1923.

![A brown coloured painting on canvas with white dots featuring several small pictures of goannas and thylacines [Tasmanian tigers] along a central curved line. The line is broken up with nine circles painted with dots. Human bones are also depicted. - click to view larger image](https://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/image/0006/784860/MA84143506-Murrdakurlies-2-1200h.jpg)

Shared histories

Thylacine histories are, of course, interwoven with those of First Nations Australians, reflecting the two peoples’ long co-habitation on the Australian continent and their shared experiences of settler invasion, violence and displacement.

Until around 3,000 years ago, thylacine lived across much of Australia, south to Tasmania and north to New Guinea. They appear in many First Nations people’s ancestral stories.

The Museum's collection includes South Australian Adnyamathanha artist Regina McKenzie’s Murrdakurlies I (Tasmanian tiger) and her daughter Juanella McKenzie’s Murrdakurlies II (Tasmanian tiger).

The artists explain that these works each represent, in very different styles, the story of a boy who disobeyed his father to take a swim in a cool waterhole and was eaten by thylacine beings, one white, one yellow, one orange or tawny, one red, one brown and one black.

Reimagining relationships

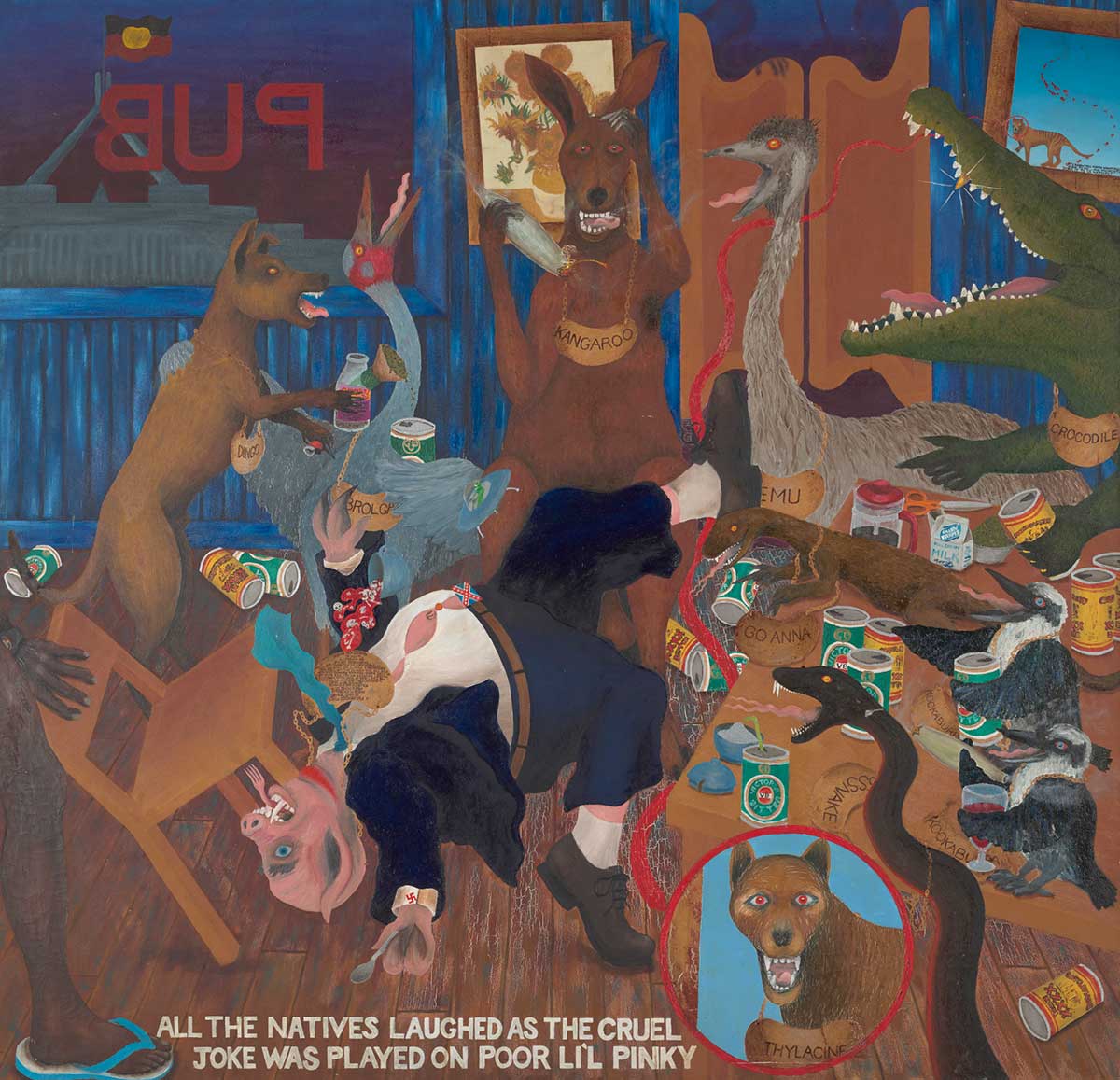

For Gordon Hookey, a Waanyi artist originally from Cloncurry in northern Queensland, thylacine symbolise the cultural and physical violence inflicted on First Nations peoples.

In his vibrant 1997 painting, All the Natives Laughed as the Cruel Joke Was Played on Li’l Pinky, held by the National Museum, Hookey reverses once widely circulated stories and cartoons caricaturing Aboriginal people as the butt of the white man’s jokes.

As Hookey reimagines this degrading tradition, native animals take over a pub’s front bar and enjoy some payback as an off-canvas Aboriginal person whips Pinky’s chair away so that he falls foolishly to the floor.

In the painting’s foreground, in a detail window from a painting on the wall, a thylacine grins delightedly, there in spirit, if not in person.

Thylacine and palawa

Thylacine lived longest with palawa, Iutruwita’s First People. In their island’s centre and east, palawa used fire to create open woodlands and grassy plains rich with pademelons and wallabies. People and thylacine, as well as other species like eagles, enjoyed this good food, keeping herbivore numbers in check.

When colonists arrived, they seized the grasslands for their stock. Palawa were murdered or exiled, and without fire-stick farming, the woodlands grew dense and difficult for thylacine to move through. Thylacine grew hungry and perhaps turned their gaze to the invader’s sheep and chickens.

Trawlwoolway artist Vicki West’s work, litter, created for the Great Southern Land gallery, responds to this shared history of exclusion and oppression.

A trio of sculptures of four- to five-month-old thylacine joeys, litter expresses palawa’s deep sense of the animal as kin and considers how settler culture sought to over-write both branches of the family.

Each joey is made from natural materials, including wallaby fur, jackey vine, bracken fern, wattle, native iris and native blueberry, over-wrapped by fencing and copper wire, metal fragments, polystyrene, waxed thread, horsehair and sheep fleece.

As West says, the sculpture invites us to consider ‘what lays beneath the surface’, drawing attention to the persistence of Indigenous Tasmanian people, culture, animals and plants, despite all colonising attempts to erase them. It also evokes how palawa practices of care for thylacine and other species' ways of life made possible settler prosperity.

Extended families

Back in the Museum’s Great Southern Land gallery, my attention eventually lifts from the gruesome and gorgeous flayed thylacine. My ears tune in to a soundscape of wind and leaves, bird calls and a strange barking – what we can record now of what a thylacine heard.

At the adjacent case, I crouch down to come eye to eye with Vicki West’s darling joeys. Below, a brushtail possum skin hat tells of one of the species that boomed after thylacine were exterminated, enabling a flourishing colonial Tasmanian fur trade.

What are we after all, without family?

On the other side of the case, native hen eggs, a Pacific black duck nest, a Tasmanian devil skull and eucalypt botanical specimens weave the story of the thylacine’s world.

These objects are not parts of thylacine or representations of them, but they too are part of the Museum’s thylacine collections, helping me understand what it meant to be a striped marsupial carnivore roaming the Tasmanian woodland. What are we after all, without family?

Reconnecting thylacine with kin

As National Museum senior curator Martha Sear later explains to me, the Great Southern Land team set out to reconnect the thylacine with its kin, returning the animal from splendid isolation as an extinction icon to dwell – narratively and imaginatively, at least – with its peoples and fellow species in Country.

This approach transforms my perception. In the gallery, a small screen plays the few minutes of extant film footage documenting living thylacine, all, of course, showing caged individuals. I’ve seen these images many times before – thylacine pacing back and forth, disturbed by men banging on their wire enclosures – but tuned to think of thylacine in relation to its community of species, I see this record in a new way.

I mark closely now how the thylacine move and turn their heads, yawn wide and flop to the ground to rest, experiencing this dance as a shadow of life among the tussock grasses.

Tied to our ancestors

Near to Vicki West’s joeys, I notice one more object, a teacup bearing the Launceston city coat of arms, the central shield supported by two fierce-looking thylacines gorged in collars and wrapped with chains.

I’m disturbed by the city choosing in the mid-1950s an emblem that perpetuates the idea of a wildly aggressive thylacine and celebrates the beast’s subjugation, but the teacup also reminds me that ‘kin’ is a difficult term.

Family is not inevitably happy and perhaps not everybody can love the thylacine. Yet, we are made by and tied to our ancestors and parents and siblings and cousins and children, regardless of whether we are thrilled, saddened or ashamed of them and their actions.

As an Australian and as a human, thylacine are part of my inheritance and the experiences they have accumulated – living and dead – shape my emotional and imaginative, as well as material, world.

Thylacine absence and resonance

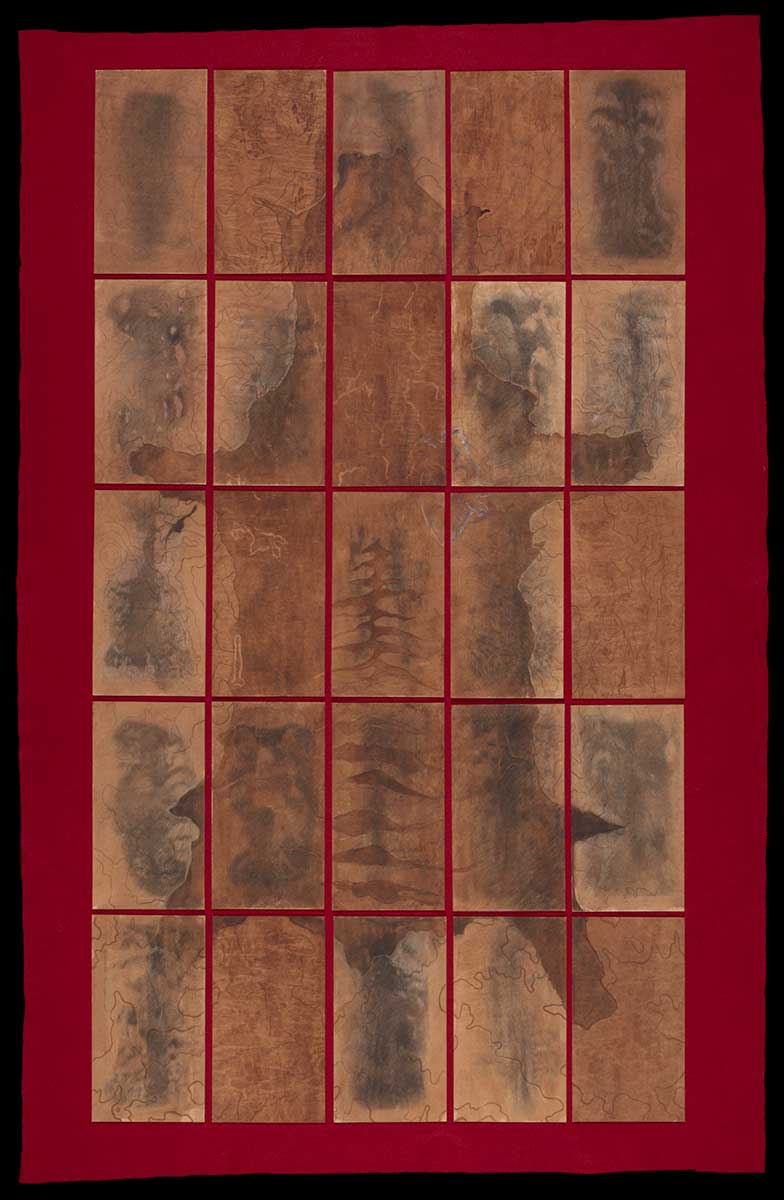

In 2013–14, Canberra-based artist Amanda Stuart, then undertaking a National Museum residency, explored the physical absence and enduring cultural resonance of the thylacine in response to the Pieman River–Zeehan area pelt.

After travelling to the region where this thylacine was shot, photographing landscapes, researching maps and recording oral histories with residents, Stuart produced a suite of evocative, multi-layered drawings.

In thylacine triptych: body, mind, spirit, painted layers of tannic acid, dingo urine, lanolin and soil pigments evoke eerie imprints of the animal’s body and skin, overlain with contour lines from maps of the area where it lived.

In the unquiet heart, Stuart considers the relationship between the thylacine and feral species, and people’s responses to these ‘unloved others’, overlaying her interpretation of a cat skin rug with the shadow of a thylacine.

Caring for what remains

For Museum staff who work with the thylacine collections, the species’ capacity to continue to build relationships, despite its extinction, is undeniable. During the development of Great Southern Land, curators and conservators spent long hours researching, contemplating and caring for the thylacine carcass now on display in the gallery.

This intimate examination led, many staff reported, to anger at the fate of the species, affection for this individual and arduous and long-lasting expressions of care and responsibility. Conservator Jennifer Brian says of the specimen that, ‘it’s a privilege to care for this incredibly rare object, to ensure that this thylacine can tell its story for as long as possible’.

Continuing power of the thylacine

The thylacine’s continuing power is undoubtedly why, despite all the evidence that the species has been gone for decades, people regularly set out into the Tasmanian forests to search for living animals, and why we feel a shiver of anticipation when scientists report that they are a small step closer to resurrecting the species.

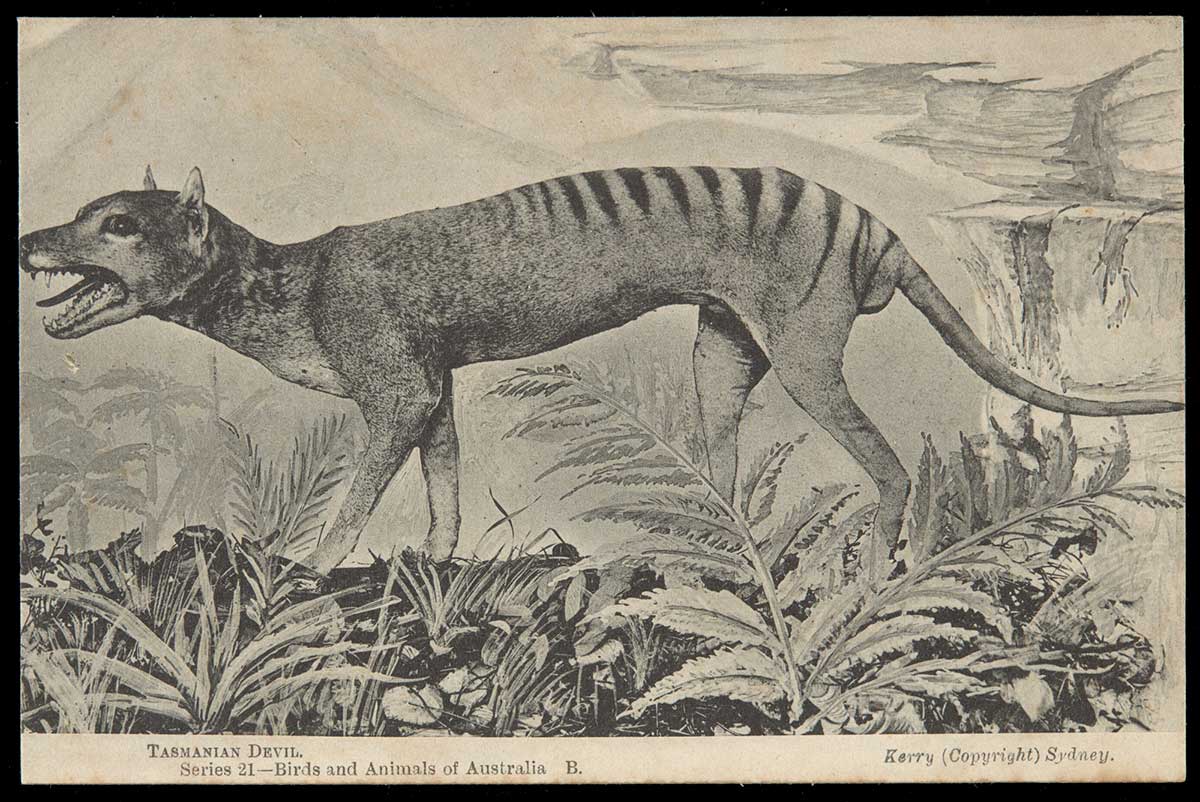

The lure of this possibility is perfectly captured in a manuscript report held in the Museum’s Bob Brown collection.

The typed and notated pages narrate how from 1967 to 1972 biologist Jeremy Griffith, farmer James Malley and physician and later politician Bob Brown overcame an incredible array of physical, financial and bureaucratic obstacles to complete a sustained series of expeditions into remote areas of Tasmania in search of the elusive marsupial.

Gifts from our kin

We want to see a thylacine run past, disappear into the trees, and release us from the sadness of its extinction. It’s probable that this will never happen, but if we pay attention to the thylacine as not simply a myth or a symbol but as an enduring member of our kin, then we can let it help us develop understanding, compassion, respect, and responsibility for the species still with us.

They have their own lives to live, and to lose them is to lose a part of ourselves.

In our collection

![A yellow coloured painting on canvas with white sponge effect featuring a seated orange coloured thylacine [Tasmanian tiger]. Circulating around the thylacine is a border made up of several smaller pictures of goannas and thylacines interspersed with lines and symbols.](https://www.nma.gov.au/__data/assets/image/0010/785422/MA424260485-Regina-McKenzie-1200w.jpg)