In 2021 the Museum will open a new permanent gallery on the environmental history of Australia, showing how everything is interconnected and interdependent. We are part of the natural environment, and our lives depend on relationships with other elements of the natural world, including other species.

We are dependant not only on organisms that are alive today, but also those from the deep past.

For example, fossil fuels such as coal are composed of plants and animals that lived hundreds of millions of years ago. Burning of these ancient lifeforms today produces energy, releasing carbon dioxide, which is altering the Earth’s atmosphere and leading to changes in the Earth’s climate.

But if we go even further back in time, some two and a half billion years, lifeforms existed that were altering the composition of the earth’s atmosphere. Without these we would never have evolved.

Watch the full Ancient life revealed: Live at the Museum video on YouTube

Oxygen

The Earth’s early atmosphere contained very little oxygen, but this began to change with the evolution of photosynthetic organisms known as cyanobacteria.

These microbes lived in shallow seas and lakes. They used sunlight, water and carbon dioxide to create simple carbohydrate molecules, releasing oxygen as a by-product.

Some of these microbes formed colonies — microbial mats — which grew as layers on the lake or sea floor. As they grew, they built structures called stromatolites, by trapping and binding the sediments that washed over them.

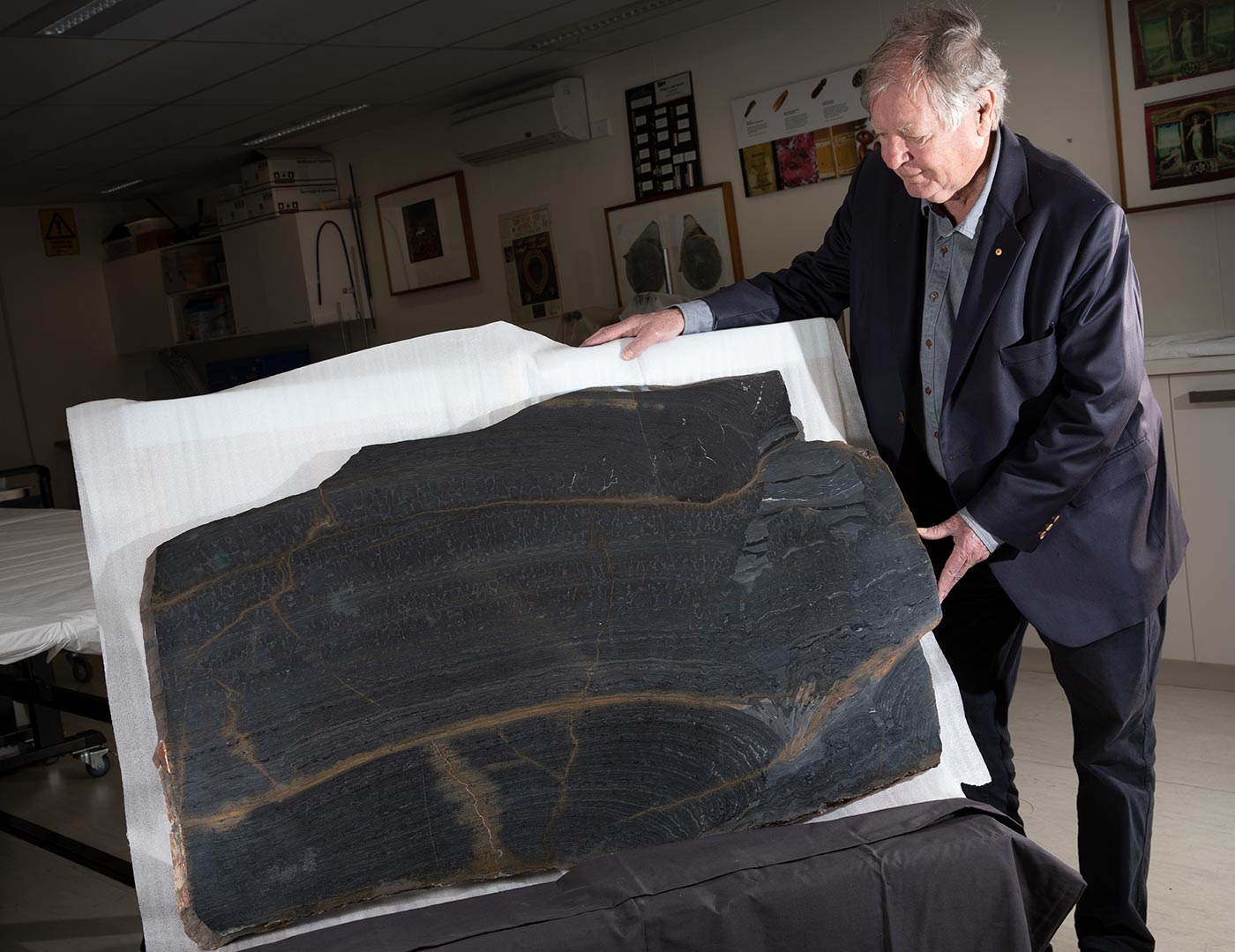

One of the oldest objects in the Museum’s collections is a 2.7 billion-year-old rock containing fossilised stromatolites from the Pilbara in Western Australia.

The rock was brought to the Museum by geologist Malcolm Walter in 2001 for an exhibition called To Mars and Beyond: Search for the Origins of Life. The rock was used to illustrate what early life forms on other planets might look like.

A life documented

The Museum’s new environmental history gallery will display a cross-section of this ancient rock.

Like the rings of a tree, the stromatolite layers represent the life history of the colony of microbes that built it. According to Malcolm Walter, the layers even reveal a period of disrupted growth when a change in climate saw more sediments being washed over the microbial mat, forcing the colony to adapt and change its pattern of growth.

Written into the earth itself is a record of life emerging, changing and responding to its surroundings, and altering the environment in ways that would influence life deep into the future.

Watch the full Ancient life revealed: Live at the Museum video on YouTube

In our collection