Of mining and meat: The story of the Canning Stock Route (part four)

William Snell's Canning Stock Route diary, 1929:

It would appear that the natives disliked the whites for some reason. The cast iron pulley wheels were broken up by the natives and iron shoot taken from the well, stood alongside a bloodwood, a life sized policeman drawn on it, and bullnosed spear driven through his heart. This is the centre of large tribes.

Another royal commission into the price of beef led to the re-opening of the stock route in 1929.

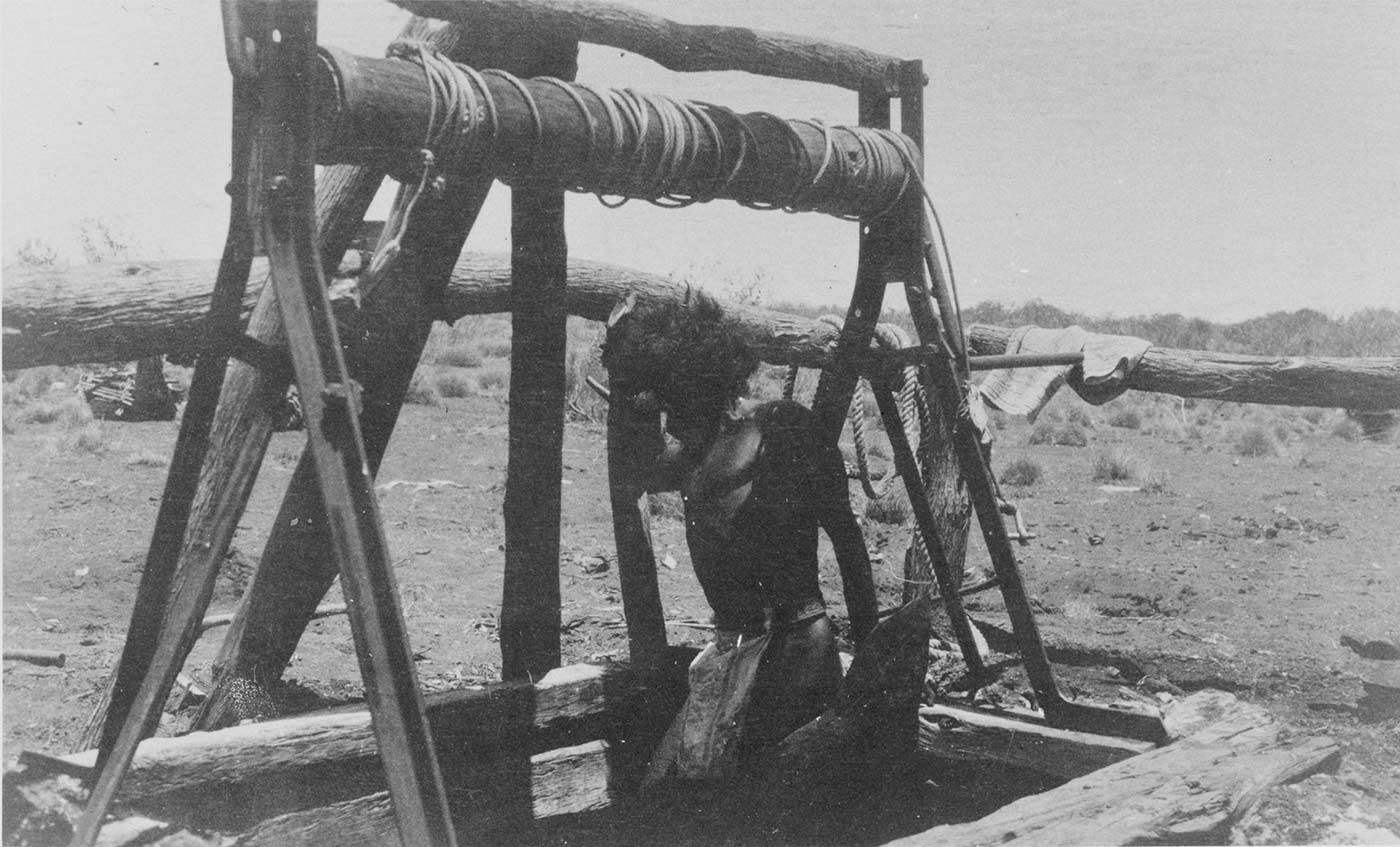

William Snell, who was commissioned to recondition the wells, was extremely critical of the structure and location of Canning's wells. He believed that they were impossible for Aboriginal people to use safely, and that their destruction was due to the anger and frustration people felt at being unable to access their own waters.

William Snell, 1930:

Natives cannot draw water it takes three strong white men to land a bucket of water with the equipment thereon it is beyond the natives power to land a bucket. They let go the handle some times escape with their life but get an arm and head broken in the attempt to get away. They then burn them down.

Snell rebuilt the wells, fitting some with ladders for easier access, but he ran out of materials before the reconditioning was completed. At nearly 70 years of age, Alfred Canning returned to complete the job in 1930–31. Unlike Snell, he encountered considerable hostility from Aboriginal people.

The reconditioning of the wells led to a new era of droving along the Canning Stock Route. Between 1932 and 1959 hundreds of cattle were moved along the desert corridor every year. As they passed through complex and dangerous cultural landscapes, cattle trampled important sites and further impacted local waters.

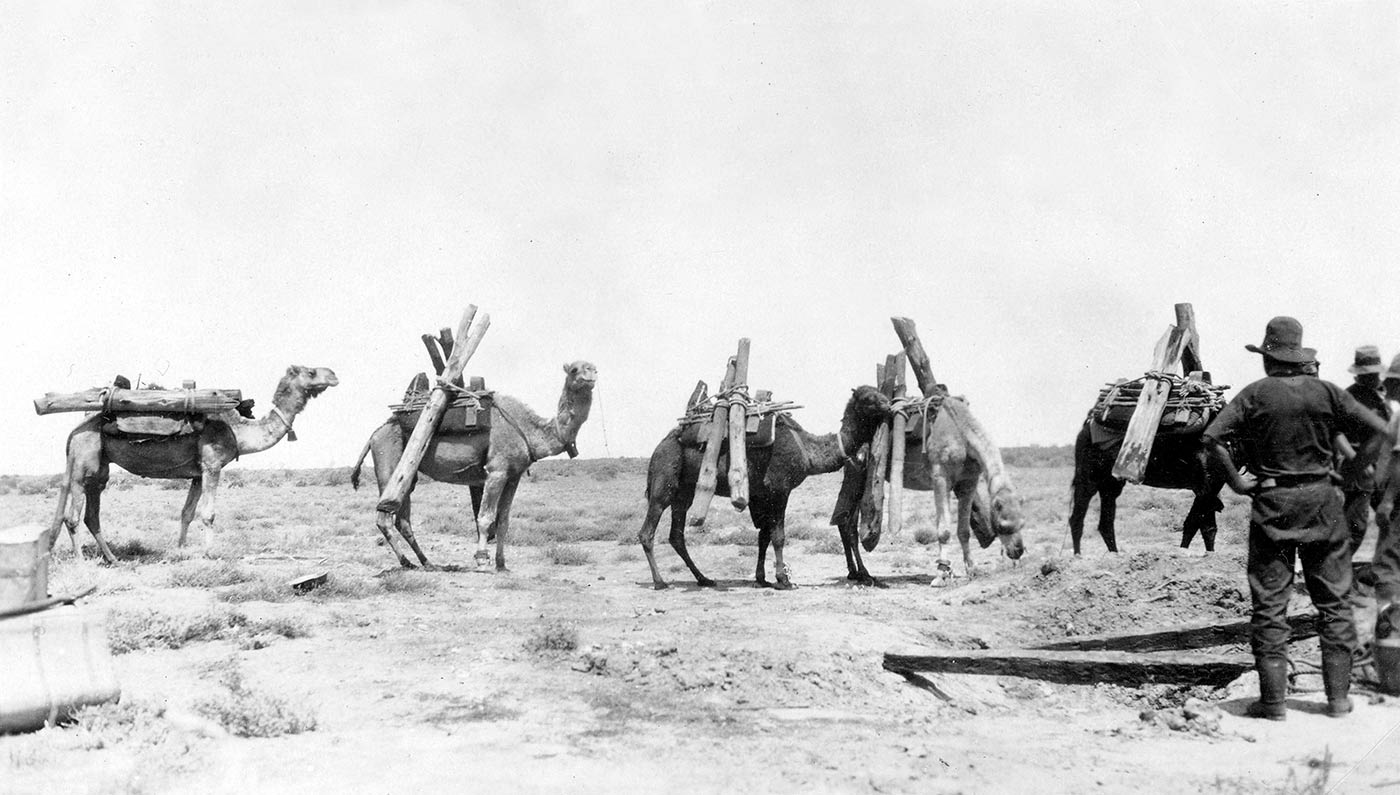

The droving era also marked a time when many of the artists in this catalogue were children growing up in the bush. Many had never seen white people before. They and their families had to make sense of the strange men and beasts that were appearing more frequently in their Country.

Kurpaliny Bessie Doonday, Halls Creek, 2009:

People used to look at kartiya [white people], that skin – white – and say to themselves, 'Might be kukurr [devil]. Ghosts coming out of the grave!'

Nyangkarni Penny K-Lyons, Fitzroy Crossing, 2008:

I thought them camels were bringing bad news. I didn't know what they were.

In the 1930s some Martu came across the tracks of a camel from a droving team. The Martu men believed the camel tracks to be the imprint of 'little fella bums' – small spirit-beings who were 'sitting' their way across the Country.

Such stories reveal an important perspective on the 'history' of the Canning Stock Route – for Aboriginal people that history unfolded within a much older story.

They perceived their changing world and made sense of it in terms of the world they knew. In their story camel tracks were the marks of spirit beings, and white men were the ghosts of Aboriginal people.

Today Aboriginal artists continue this tradition in reverse, revealing their world to audiences through painting.

Just as Martu came to realise that camel tracks were not the marks of ancestral beings, so might these audiences see that the ancestral tracks that mark the canvas of contemporary paintings are not strange traces from another world, but rather the intimate impression of worlds intersecting.

In many cultures history is understood to be a sequence of events unfolding in time: Canning surveyed the stock route in 1906–07, built the wells shortly after, and fixed them in 1930–31. This was followed by an era of droving that continued until 1959.

For the people of the Western Desert, however, stories about the past are defined not by time but by place – the specific locations or Country in which the events occurred. These are the places where history happened.

For the people who belong to this Country, history is never past, but lives on in the land today, kept alive through their oral and artistic traditions. Desert painters explore their vision of the Canning Stock Route through the stories of the Country that it cut across. They put history in its place.

The Canning Stock Route collection reveals the ways in which Aboriginal artists interpret the events of the past on their own terms. The collection, and the exhibitions that emerge from it, invite audiences to share in these perspectives, to imagine themselves as part of a bigger story than conventional history allows.

Of mining and meat: