Drawing a line in the sand: The Canning Stock Route and contemporary art (part two)

Jeffrey James, Kilykily (Well 36), 2007:

All these waters are all our family trees.

The Canning Stock Route project began with the recognition that there were artists from each of the art centres surrounding the stock route who had historical and familial connections to it and adjacent Countries.

It was well known that many of Western Australia's most celebrated Indigenous artists, including Eubena Nampitjin, Nyuju Stumpy Brown, Billy Thomas, Donald Moko, Wimmitji Tjapangarti, Spider Snell and Patrick Tjungurrayi, have direct historical connections to the Canning Stock Route.

What could not have been anticipated, before people came together to share their stories throughout the life of the Canning Stock Route Project, was the extent of these family connections between seemingly unrelated artists from geographically diverse art centres.

Martumili artist Jakayu Biljabu was married to Warlayirti artist Eubena Namptijin's brother. Eubena herself helped 'grow up' – or raise – Yulparija artist Donald Moko and Martumili artist Nancy Chapman. Kayili artist Jackie Giles's sister was Warlayirti artist Elizabeth Nyumi's mother. And Papunya Tula artist Charlie Wallabi was somehow closely related to everyone.

The depth and density of these relations across the artistic compass of the Western Desert is somewhat disorienting for those used to thinking in geographic terms of 'Balgo' or 'Bidyadanga' artists.

What these relationships that cut across art centres highlight today is the history of those 20th-century movements, both along the stock route and away from it, that separated people from their Country and from their families.

Among the most striking examples of someone who exemplifies the relationship between social and artistic dispersal around the Canning Stock Route is a man who is not regarded as a Western Desert artist at all. Rover Thomas was born at Yalta, a soak just north of Kunawarritji (Well 33), and grew up around the Canning Stock Route in the 1930s.

After the death of his parents, Rover met up with drovers travelling back along the stock route and followed them north into an improbable future in which he became one of Australia's greatest artists. [2] In his wake other waves of contemporary Aboriginal art, less obvious and less commonly understood, fanned out across the desert.

As Rover moved north, his sister Nyuju Stumpy Brown followed, travelling first to Balgo and later Fitzroy Crossing. Rover's other sister, Kupi, gave birth to Mary Meribida, who left the desert in one of the westward migrations that took people to Bidyadanga. Rover's older brother, Charlie Brooks, moved south to Jigalong, where his son, Clifford Brooks, was born.

Rover's extraordinary trajectory represented the rule not the exception. Just as his siblings dispersed to Balgo, Bidyadanga and Jigalong, a similar scattering was also the fate of many of the families whose lives intersected the Canning Stock Route.

Kin moving at different times, and for different reasons, out of their home Country found themselves settled on missions and stations at vast distances from one another.

It was in these small communities that painting flourished in many localised forms. And so in one small family group such as Rover's, we can find artists from four geographically and stylistically diverse schools of contemporary desert art.

When we find Bidyadanga artist Donald Moko painting Rover Thomas's birthplace Yalta, or Papunya Tula artist Richard Yukenbarri painting Kayilli artist Norma Giles's birthplace Kalyuyangku, it becomes clear that the identities of contemporary artists are constituted as much by relationships across art centres as they are by those within them.

That Jan Billycan, who lives in Bidyadanga, and Nada Rawlins, who lives in Wangkatjungka, are painting the same place, Kiriwirri, shows how greatly the paths followed by people from the same Country had diverged.

There is perhaps no greater embodiment of the family connections underpinning the story of contemporary desert art than the men's collaborative painting, Kunawarritji to Wajaparni, that was produced at Kilykily (Well 36) in 2007 as part of the 'return to Country' trip.

The work was painted by eight men (Patrick Tjungurrayi, Jeffrey James, Helicopter Tjungurrayi, Charlie Wallabi, Clifford Brooks, Richard Yukenbarri, Peter Tinker and Putuparri Tom Lawford), representing five different desert art centres.

The painting makes no reference to the line of the stock route at all. Rather the artists took a cross-section of the Country intersected by wells 33–38 and used it to explain the vast relational logic of their social world.

Jeffrey James, Well 36, 2007:

All this waters from that line to this line are all our family trees where our mob used to go from one waterhole to another, all as one people. This is our family tree this painting ... Yeah, some mob came from here, some from there; all met up along these wells, jilas, before wells. People from the north, south, east and west all came together.

The painting is made up almost entirely of different shades of white, but the variations in dotting technique reveal the hands of separate artists and the distinctive styles of different art centres. These artists meet around the wells, as their ancestors once did, to share a common story for that Country.

It is revealing that such a small part of the stock route Country should have been painted by men from five art centres spread across the Western Desert.

To see family members painting the same Country in very different styles, or indeed to see people from the same art centre painting different Country in the same style, is to begin to piece together the history of contemporary desert painting.

Of course, not every artist paints Country along the stock route: some belong to Country further east or west. Not everyone followed the stock route to their current communities, or even encountered drovers. Indeed, many intentionally avoided the route.

But all of the artists represented in the collection consider themselves part of the story of this Country, a story that, while often organised around the Canning Stock Route, ultimately surrounds, absorbs and overwhelms it.

The Canning Stock Route story helps to contextualise desert painting in time as well as space. While this story allows us to make sense of the geographical and familial relations across contemporary desert art, it also helps us to reframe that art in terms of a much longer art history.

Acrylic paintings and other contemporary mediums are but the latest expression of a century of cross-cultural communication mediated through the visual languages of the desert.

When Alfred Canning was carving his commercial channel through the desert it was, while often a matter of coercion, nevertheless a process of aesthetic translation. Canning would sometimes ask the Aboriginal men to draw, in the sand, a diagram of the waters to be found north or east of their current location.

You would know the native name of two of the waters behind you. You would draw them on the ground and clear a fairly large space on the sand, and then the natives would draw other waters at proportionate distances to those wells you put down, and get them to point to them with their hunting spear, and I would take the bearings. After we had taken the bearings I would know about the direction I wanted to go ... That is how the natives were so extremely useful to us. [3]

And as soon as the bearings were secured, using a spear point as 'compass', doubtless these sand drawings were casually effaced by Canning's boot or a guide's hand.

Canning did sometimes endeavour to create more lasting records: 'I gave [Tom, one of the guides] a lead pencil to try and draw a map himself, and then he could put it through his nose as an ornament.' [4]

While Tom was not inclined to use the pencil for either purpose, he used his skill at sand drawing to other creative ends; when the drawing was finished, and Canning was distracted, Tom seized his chance to escape. This sand drawing, like the many others Canning used to survey the stock route, was erased. These are the missing maps.

Ngarralja Tommy May, Nyarna (Lake Stretch), 2007:

I know that kartiya fella [white man] been putting all the road. Still, I reckon, only lately. That road been put by that Canning mob lately. But we trust this bloke [our Dreamtime ancestor]. Dreamtime, that's really true. Before, used to be blackfella country.

Canning failed to collect more lasting records of the Aboriginal perspective on the desert. Instead, we have his map, which, despite its austere beauty, tells us nothing of the Indigenous world it cut through. Maps encode the perspective, the ideologies and the values of the people who make them.

Canning's map reveals only the bare details of feed and water to either side of the narrow corridor he was employed to survey. On either side of this channel, the country is seemingly empty, without value to the settler imagination.

True Map of Canning Stock Route Country by Billy Patch (Mr P) [5]

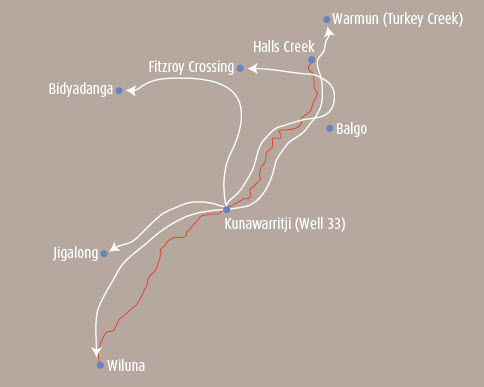

In 2008 a senior Martu man, Billy Patch (Mr P), sought to explain the deficiencies of Canning's map, and modern tourist maps, by creating an alternative map of the desert Country the stock route bisected.

He began by laying a network of horizontal and vertical lines through the sand. The intersecting points on the grid marked different Ngurra, camps or water sources, while the lines connecting them denote the songs that are sung for these sites and the journeys people took between them.

It was a grid symbolising the cultural topography of the desert. Then, over the top of that he drew a thin line curling between two points, Wiluna and Billiluna.

That line, the Canning Stock Route, cuts through a pre-existing network of cultural and political boundaries, songlines and laws which were invisible to the early explorers (see also the Dreaming tracks map, which expresses a kindred Aboriginal perspective).

Minyipuru (Seven Sisters) by the late Muni Rita Simpson, Rosie Williams and Dulcie Gibbs, appears to be a complete inversion of Canning's map. While the stock route is present, as a red ribbon cutting through the artists' Country, it is surrounded by the waters and Dreaming sites of the Minyipuru.

Where Canning's line representing the stock route was intricately detailed and the Country either side of it was blank, here the perspective is reversed. The women's painting has the stock route as a negative red space through the centre of the painting, surrounded on all sides by the abundance of Country and the authority of another, much older story: one in which the incursions of 20th-century history, however radically disruptive they may have been to the material conditions of people's lives, remain merely as scratches on the surface.

Ngarralja Tommy May, Nyarna (Lake Stretch), 2007:

Righto. This story about Dreamtime. Dreamtime people before Canning. Before whitefella come with a camel Dreamtime people were there.

Minyipuru was painted on the stock route in 2007, during the 'return to Country' trip. At the end of that trip, Mangkaja artist Ngarralja Tommy May drove down to the final camp from Fitzroy Crossing.

He brought with him a painting he had recently completed, Kurtal and Kaningarra. It depicted two of the ancestral jila men, whose journeys are inscribed in the Country around the northern end of the stock route. On the banks of Nyarna (Lake Stretch), Ngarralja laid the painting down and proceeded to explain what it meant.

Ngarralja Tommy May, Nyarna (Lake Stretch), 2007:

That Canning Stock Road they been only put 'em lately. It wasn't Canning Stock Road before. Before, it was these two men [Kurtal and Kaningarra], Dreamtime story. Before, it was blackfella Country.

Ngarralja explicitly places the story of the stock route within the context of a deeper history and a longer story: the Dreaming or Jukurrpa. This autonomy and authority of the Jukurrpa in relationship to the whitefella road is expressed in different ways by artists throughout the collection.

Patrick Tjungurrayi sets the historical line of the Canning Stock Route against the tracks of the Tingari Jukurrpa, which dominates the Country east of the stock route. Cast in this mythic shadow, the stock route wells become absorbed into the Tingari iconography of concentric squares. Whereas in Minyipuru the stock route is surrounded by the Jukurrpa, here it is reclaimed by it, and reinterpreted though it.

Another painting that reintegrates the stock route into the Country it passed through is Kumpaya Girgaba's Kaninjaku.

The name 'Kaninjaku' is Kumpaya's desert-inflected translation of 'Canning Stock Route' but, among the undulating sandhills running west to east in this painting, the road itself is barely perceptible. At best, it is a topographic kink in the colour around Kunawarritji. The road has been absorbed into the artist's voice and vision of her Country.

The stock route is used as a cross-cultural reference point, visually and verbally, in several important works in the collection, but in many more it remains unnamed, invisible as either a landmark or narrative.

Although collaborative paintings such as Kunkun cover vast tracts of desert, most artists paint the relatively small areas of Country with which they are intimately associated: their waters, and the small section of a song or Jukurrpa narrative for which they are custodians.

Male artists such as Wimmitji Tjapangarti, Brandy Tjungurrayi and Charlie Wallabi paint sections of the Tingari Jukurrpa for which they have authority, and likewise many women paint different sections of the Seven Sisters Jukurrpa. These paintings reveal the links, made manifest through shared Jukurrpa narratives, between sites and people across the desert.

Stories of the jila men help us understand the social and environmental essence of the jila Country in the Great Sandy Desert. Paintings by Spider Snell, David Downs and Jakayu Biljabu reveal the extent to which these areas of the desert, and the people who paint them, are linked together by epic narratives.

It is through attending to these paintings, and to the relationships between them, that we can better understand the desert world the stock route cuts across.

Pukarlyi Milly Kelly, Jigalong, 2009:

Puntawarri. My home. I was walking around little naked one!

While the collection as a whole presents a vast political tapestry of Dreamings, desert sites and boundaries that were interrupted by the currents of 20th-century history, individual paintings return us to the often overlooked intimacy of desert art.

Pukarlyi Milly Kelly's tiny brown painting, Puntawarri, rough and rusted, has a little yellow space in the corner: this was Milly's home, the shelter she lived in as a girl with her family.

Jewess James contributed a painting that is no less affecting; Kulyayi shows her family camping long ago, their fires burning between them as they sleep. It was such homes as these that colonial history interrupted.

Notes

2. For more on Rover Thomas, see Rover's legacy.

3. Alfred Canning, evidence given in the 1908 Royal Commission into the Treatment of Natives by the Canning Expedition party (Commission ref. 3515)

4. ibid. (Commission ref. 3496).

5. With thanks to the family of Mr P for permission to reproduce this image. Thanks also to Peter Veth and Jo McDonald of the Australian Research Council-funded Australian National University Canning Stock Route Rock Art and Jukurrpa project, for which this photo was taken.

Drawing a line in the sand:

You may also like