Drawing a line in the sand: The Canning Stock Route and contemporary art (part three)

Manmarr Daisy Andrews:

It is beautiful Country with sad feelings from the past.

None of the artists painting today were alive between 1906 and 1910, the period during which Canning surveyed the stock route or first sank the wells. Despite the fact that the existence of the road predates the births of all the artists in the collection, in the Aboriginal worldview of the desert Country the stock route happened 'only yesterday'. [6]

Many desert painters who were born in the height of the droving era (1930s–50s) first experienced their Country as something that included the Canning Stock Route and the beings that it conveyed seasonally through their world.

They were therefore as familiar with the stock route wells and their associated tales as they were with their rock holes and Dreaming stories. Several paintings in the collection therefore address specific historical events on and around the stock route.

Many accounts of early cross-cultural encounter around the stock route – seeing white people and strange animals, or trying the new foods they brought with them – are told with great humour.

But, just as often, these initial experiences of contact involved conflict. Some paintings in the collection, such as Mayapu Elsie Thomas's Natawalu, address specific conflicts remembered by both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people.

Other artists, such as Daisy Andrews and Dadda Samson, recall horrific events that have never featured in the official catalogue of historical 'facts'. Other paintings are catalogues unto themselves.

Patrick Tjungurrayi accompanied his work (below) with a series of oral histories recorded during the project and the process of painting. Tjungurrayi painted the stock route waters between Well 33 and Billiluna station in the north, narrating the unwritten history of those sites.

At Lipuru (Well 37), he noted the murder of a white man by members of his family, while between Tiru (Well 41) and Kulyayi (Well 42), he painted the site where white men massacred a desert family.

Tjungurrayi also recalls other killings at Jintijinti and Jikarn (wells 45 and 50), where Aboriginal people fell victim in various ways to the stock route and the troubled history that coursed along its path.

Patrick Olodoodi (Alatuti) Tjungurrayi, Jikarn, 2007:

This is their Country. And they all died, whole lot. They got matches and chained them, made them sit down and put them in the fire. They fired the people, you know. Jikarn people. Those [white] people were bad. They killed the people from this Country. There's nobody left from Jikarn.

Patrick Olodoodi (Alatuti) Tjungurrayi, Kiwirrkurra, 2007:

Bones are still there where they killed people ... I been see those bones. (Peter) Kurtiji was a little kid, he was crying. His mother was dead there. I will show you.

These conflicts, like so many on Australia's frontier, are missing from the annals of history because they were not written down. But they were not forgotten.

Clifford Brooks, Wiluna, 2006:

We wanna tell you fellas 'bout things been happening in the past that hasn't been recorded, what old people had in their head. No pencil and paper. The white man history has been told and it's today in the book. But our history is not there properly. We've got to tell 'em through our paintings.

Clifford Brooks is an artist for whom painting is an intentional act of historical redress. His painting Blood on the Ground outlines events surrounding Clifford's father's search for his brother, Rover Thomas, and the subsequent discovery of a massacre.

Clifford Brooks, Wiluna, 2006:

He been get up on a sandhill and he been look down ... whitefella massacre. They been get shot: men, women and children.

This massacre may be the same one recorded by Patrick Tjungurrayi, but it is nowhere recorded in official histories. In Brooks's painting the massacre sits outside the stock route and outside mainstream history, like much Aboriginal history itself.

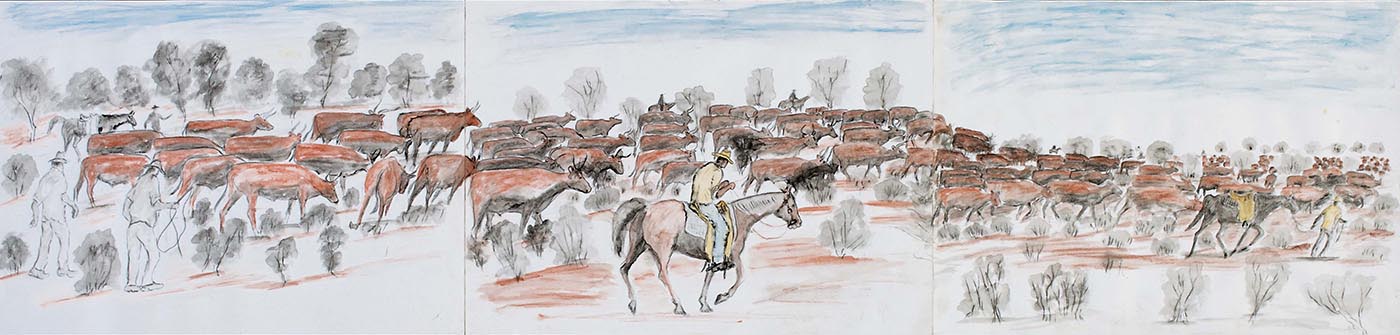

These explicit acts of redress in contemporary artistic practice are not confined to histories of frontier violence and conflict. Mervyn Street's record of Indigenous drovers working cattle on the stock route counterbalances the usual valorisation of white drovers such as Wally Dowling.

Mervyn Street, Jilakurru (Well 17), 2007:

Lotta old people telling me 'bout they used to drove from Billiluna straight across to Wiluna. But they're not in the photos, they got no name. Nothing. They gotta be part of this droving story.

This retelling of history is nothing new in Aboriginal art. East Kimberley artists such as Paddy Bedford, and indeed Rover Thomas himself, have a long tradition of painting historical narratives, station stories and massacres. Most Indigenous artistic traditions in Australia – whether on canvas, bark or rock walls – reveal similar historical depths.

The value of this collection is to be found not simply in how it fills the gaps or corrects the facts of established histories. What is important is the way those events, our history, are imagined and remembered through alternative world views, which provide a different perspective on the past and on what that past continues to mean today.

For Aboriginal people, the creation of the stock route, the sinking of the wells, the coming of the drovers did not happen in time, as we commonly think of it, but in place. Events do not just happen in the desert; they happen here or there, in the places – Ngurra, or Country – that people paint.

Mayapu Elsie Thomas, Ngumpan, 2008:

At Natawalu an Aboriginal man speared a kartiya, then that kartiya got a rifle and shot him. Right [at] Natawalu. That's the place I painted now.

In this place-based view of the world, stories from the Jukurrpa, from family, from colonial history and from personal experience, are all layered in the sites where they happened. Country is a kind of memory.

Natawalu, in the paintings of the Canning Stock Route collection, is not just the site of the first conflict on the stock route, but also the place where there occurred a cross-cultural encounter laced with humour and goodwill: the rescue of Helicopter Tjungurrayi.

It is where desert families and ancestral beings rested on their travels, and the place from which many artists began their own epic journeys out of their traditional way of life. Natawalu has been overlaid with new narratives for more than 100 years, but it was long ago inscribed with stories and meanings that 'history', in the form of the stock route, came to intersect.

Nowhere was the intersection of worlds more dramatic than at Kulyayi. Kulyayi was one of the ancestral jila men who had become a rainbow serpent, inhabiting the water that would become Well 42 on the stock route. According to the artist Jewess James, white men killed Kulyayi when they built or rebuilt the Canning Stock Route well over his water.

Milkujung Jewess James, Ngumpan, 2007:

They killed that jila for that water Kulyayi. They found him at his own waterhole and killed him.

Kulyayi's death marks the clash of history and the desert world. This death of an ancestral being might be taken as a metaphor for the collision of world views; but it is also very real. When the well was built, and the snake was killed, people's relationship to Country was irrevocably changed.

The homes of desert people were organised around waters, which were created by ancestral energies and around which the stories, sentiments and logic of desert life were forever woven. It was these waters that the stock route usurped, and these stories that it stumbled into.

Lily Long's painting, Tiwa, provides a final example of a place where personal, historical and ancestral threads entwine around the image of the 'government well'.

'This is the Canning Stock Route,' the artist begins, and we are invited to imagine ourselves with Lily as a child perched on the hill watching the incongruous marvel of the drovers and 500 head of bullock drinking at her family waterhole. Then as those memories shift to the horizon of hills that oversee the well, we realise these events occurred within a sacred landscape of much older narratives.

One of those stories relates to the poisoning of the ancestral heroes, the Wati Kutjarra, by an ancestral woman. In a sad twist on the tale of this Country, Lily notes that her own uncle was in turn poisoned by drovers on the stock route.

In one painting about one place, these threads of history, memory, art and Country have been interwoven. Stories of cross-cultural conflict on the Canning are prominent in people's oral histories, and appear as themes in contemporary art, but they also remain layered within alternative world views that challenge us to consider the nature and impact of such conflict in the stories we tell about Australia.

What is a rainbow serpent if it can be killed by human action? What was the Canning Stock Route if its impact was, among so many other things, to kill Kulyayi? How is Australian history to be understood on these other terms? The paintings of the Canning Stock Route collection invite us to ask these questions.