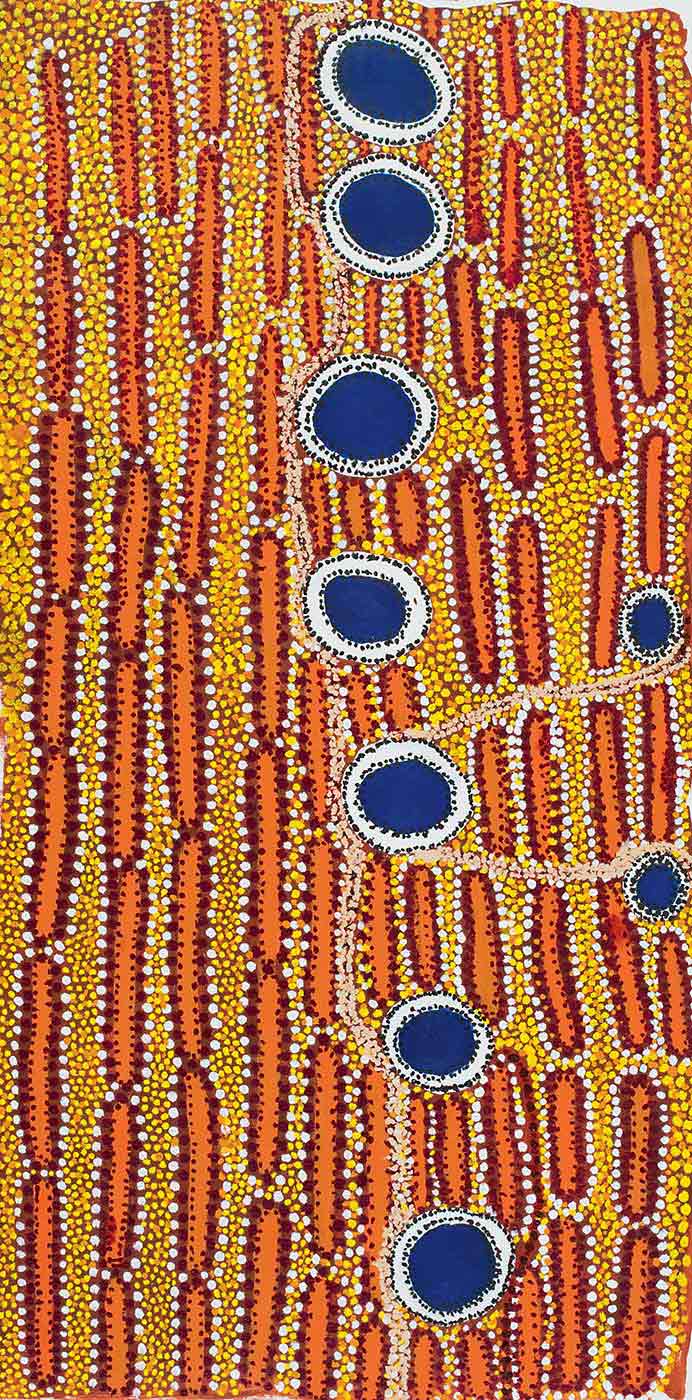

Jeffrey James, Kilykily (Well 36), 2007:

All these waters, from that line to this line, are all our family trees. Where our mob used to go from one waterhole to another, all as one people. This is our family tree, this painting.

Walyja means ‘family’, but in a much wider sense than many non-Aboriginal people may be familiar with.

In the Country crossed by the stock route, the experience of kinship and family is shaped by the desert’s harsh environment, which required extensive travel and cooperation between distant groups. Here family ties include social and cultural, as well as genealogical, relationships, linking artists from the central desert to the Kimberley coast.

'Ngurra kuju walyja' is the term used by desert people to describe what binds them to each other. Translated literally as ‘Country one family’, it encapsulates two seemingly contradictory ideas: that all of the people who belong to the desert Country are related as one family, and that there are many distinct cultural and linguistic family groups, all with specific responsibilities for their own areas.

Although proud of their distinctive identities, these language groups are united by their shared kinship, histories, ceremonies and relationships to Country.

When the Canning Stock Route was opened up to droving, it led to new connections being forged between peoples without previous cultural or historical ties. Aboriginal stockmen and women from Balgo, Billiluna and Fitzroy Crossing married and settled in Wiluna, thereby establishing familial ties between the northern and southern ends of the stock route, which remain strong today.

But these new patterns of movement also caused many families to be split apart, as brothers, sisters, parents, uncles, aunts and grandparents journeyed in different directions at different times. Some followed the drovers north or south; others shunned the sometimes dangerous stock route and travelled east and west.

Most settled at the missions, stations, towns and settlements on the peripheries of the deserts. During periods of drought, relatives who had earlier come into these settlements sent back word of the abundant food supplies to be found there.

In these new places, many people were not only far from their traditional homes but also separated from their closest relatives. Some would not be reunited for decades. Others returned to the desert, looking for family members who had stayed behind, or because they felt homesick for Country and for the old ways of life.

Some of the last desert people to make the permanent transition from nomadic life to life in a community were the families of couples who had chosen self-imposed exile for marrying in defiance of traditional marriage laws.

Fortunately, today these families are able to maintain close connections with their relatives across the desert. Much as they did in the past, Aboriginal people still visit their kin regularly, for ceremonial, social and familial reasons. It is just that now they make their way across the vast distances by bus, car or plane.

Explore more on Yiwarra Kuju