Yunkurra Billy Atkins, Jigalong, 2008:

I’m telling you that that cannibal mob is out there and they are no good.

The power of the Jukurrpa, and of the ancestral beings whose actions shaped the world, remains present in the land. These ancestral beings, who often transformed into the landscapes they created, can also affect living people and events. Along the Canning Stock Route, this influence is felt most powerfully at Kumpupirntily (Lake Disappointment).

Kumpupirntily is a vast dry salt lake that dominates the country east of the Canning Stock Route, from wells 18 to 21. Explorer Frank Hann came across it in 1896. Having followed creeks that flowed inland in the hope of finding a freshwater lake, he named it after the disappointment he felt.

Hann knew nothing of Kumpupirntily’s cultural importance. One of the most dangerous areas in the Western Desert, the lake is home to cannibal beings known as Ngayurnangalku (the word means ‘will eat me’).

The Ngayurnangalku live under the surface of the lake, in their own world, with its own sky and a sun that never sets. They are said to resemble people, except for their large fangs and the long curved fingernails they use to catch and hold their victims.

Cannibals and the Canning

Martu people will not set foot on the lake’s salt-encrusted surface for fear of those who live beneath. According to Yunkurra Billy Atkins, even passing by can be dangerous:

When the wind is blowing we can go there, can go past. If the wind stops you can’t go any further, because he is there.

Such places made life difficult for Aboriginal people working with the drovers. As a boy, Frank Gordon travelled the route several times with his parents:

[Cannibal] there, properly. Might kill me fellas. All the devil. We was frightened all the way along.

As they approached the lake, Aboriginal stockmen would muffle their horses’ bells so as not to alert the cannibals to their presence. Yunkurra also describes how they sought the aid of local maparn (magic men):

Drovers used to get a maparn to go front, make a big wind come up so they could go through.

The cannibal Jukurrpa

In the Jukurrpa, when Ngayurnangalku were living all over the desert, they came together for a big meeting at Kumpupirntily, and debated whether or not they should stop eating people. Jeffrey James continues the story:

That night there was a baby born. They asked, ‘Are we going to stop eating the people?’ And they said, ‘Yes, we going to stop,’ and they asked the baby, newborn baby, and she said, ‘No’. The little kid said, ‘No, we can still carry on and continue eating peoples,’ but this mob said, ‘No, we’re not going to touch.’

Following the baby, one group continued to be cannibals, dividing the Ngayurnangalku forever into ‘good’ and ‘bad’. The bad people remained at Kumpupirntily, but the good were kept safe by ‘bodyguards’.

The bodyguards were saving all the people. Sandhill in the middle of the lake separates good people and bad people.

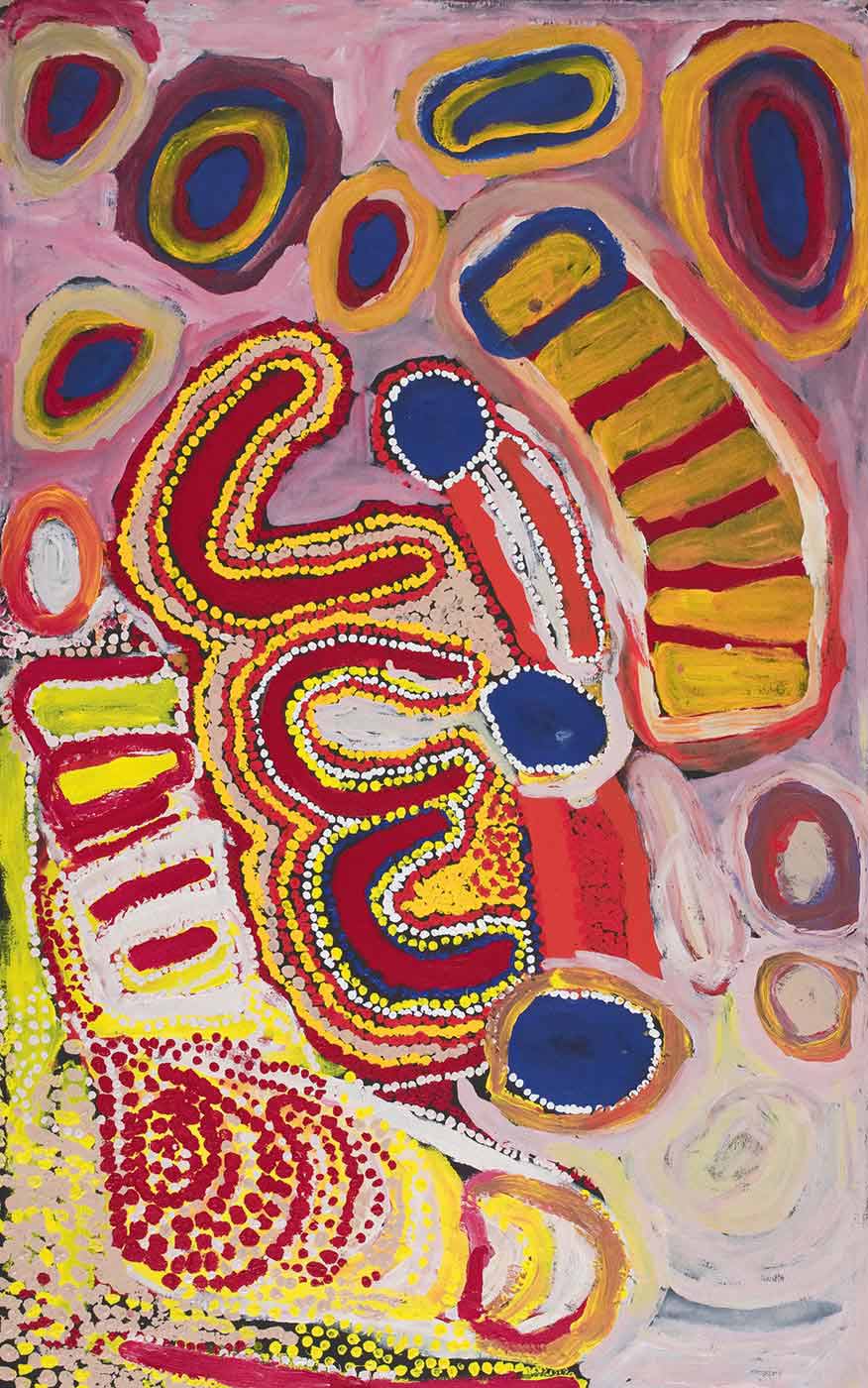

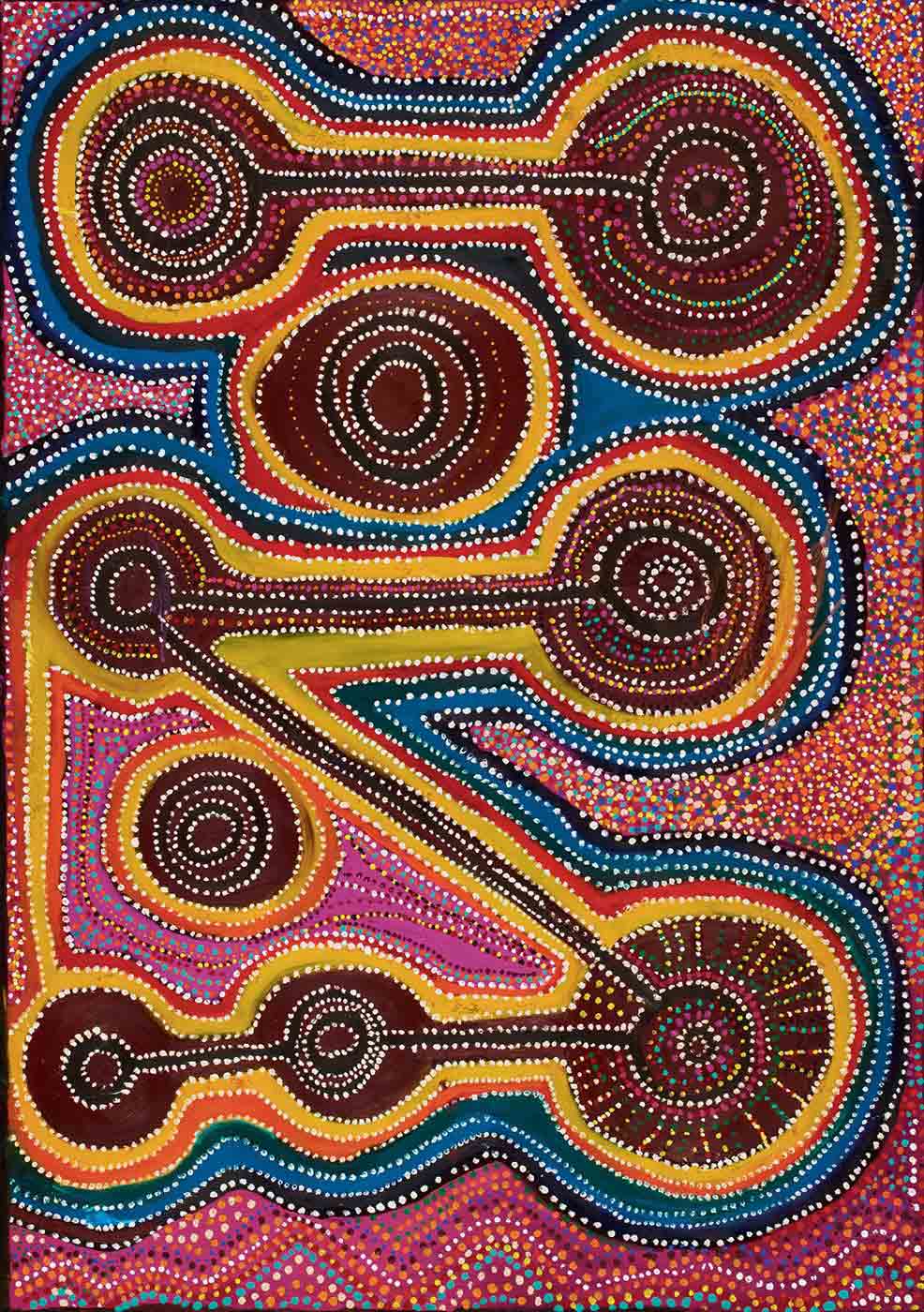

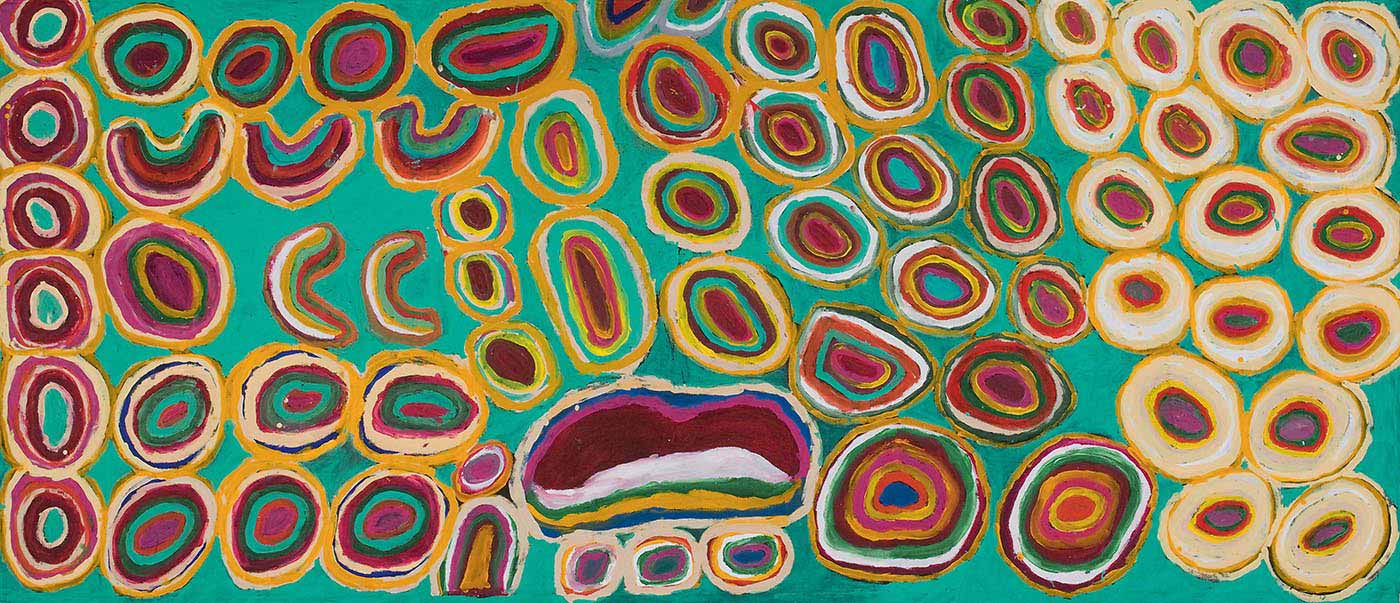

Kumpupirntily by J. Biljabu (dec.) and Dadda Samson

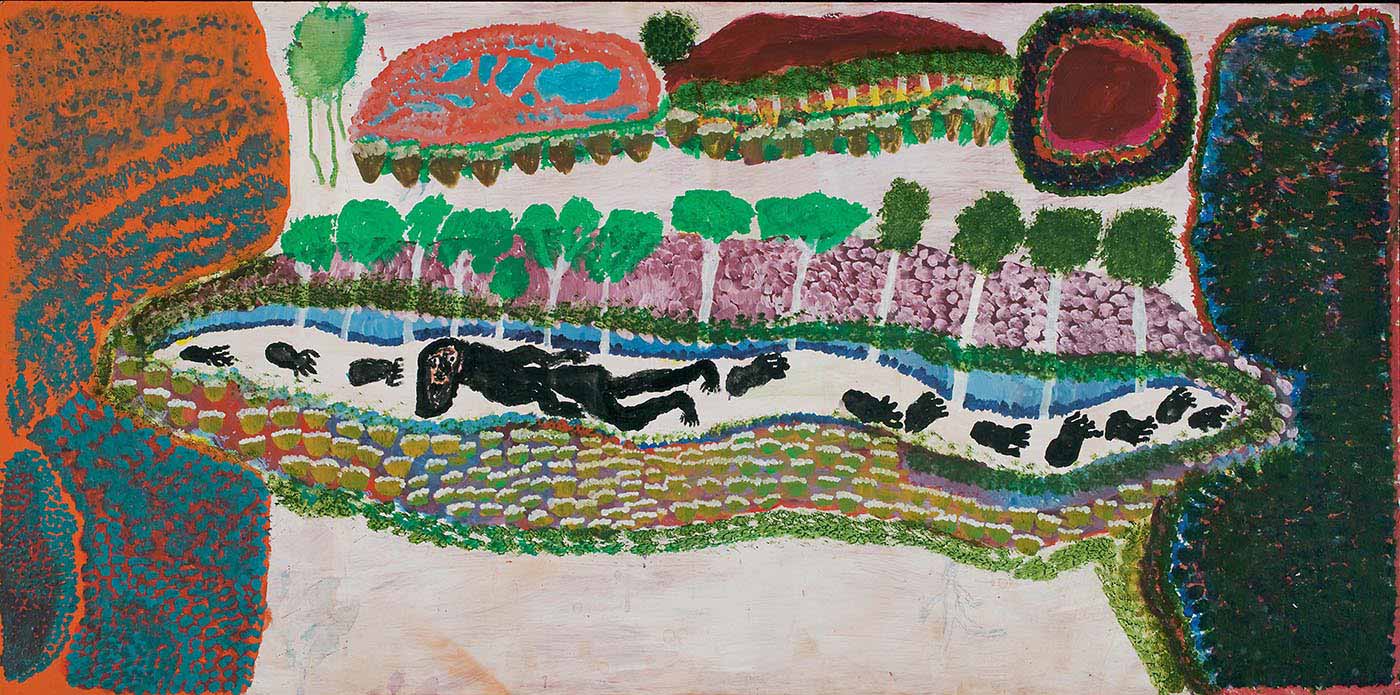

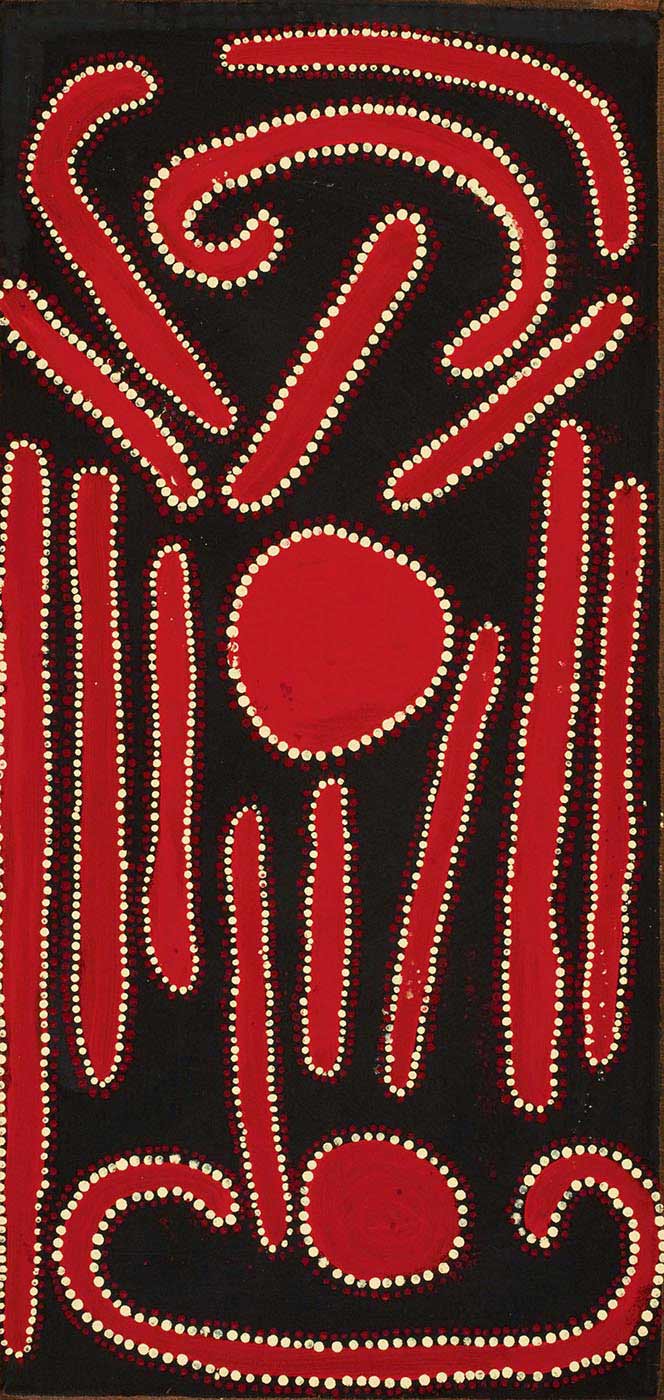

Cannibal Story by Billy Atkins

Kumpupirntily Cannibal Story by Billy Atkins

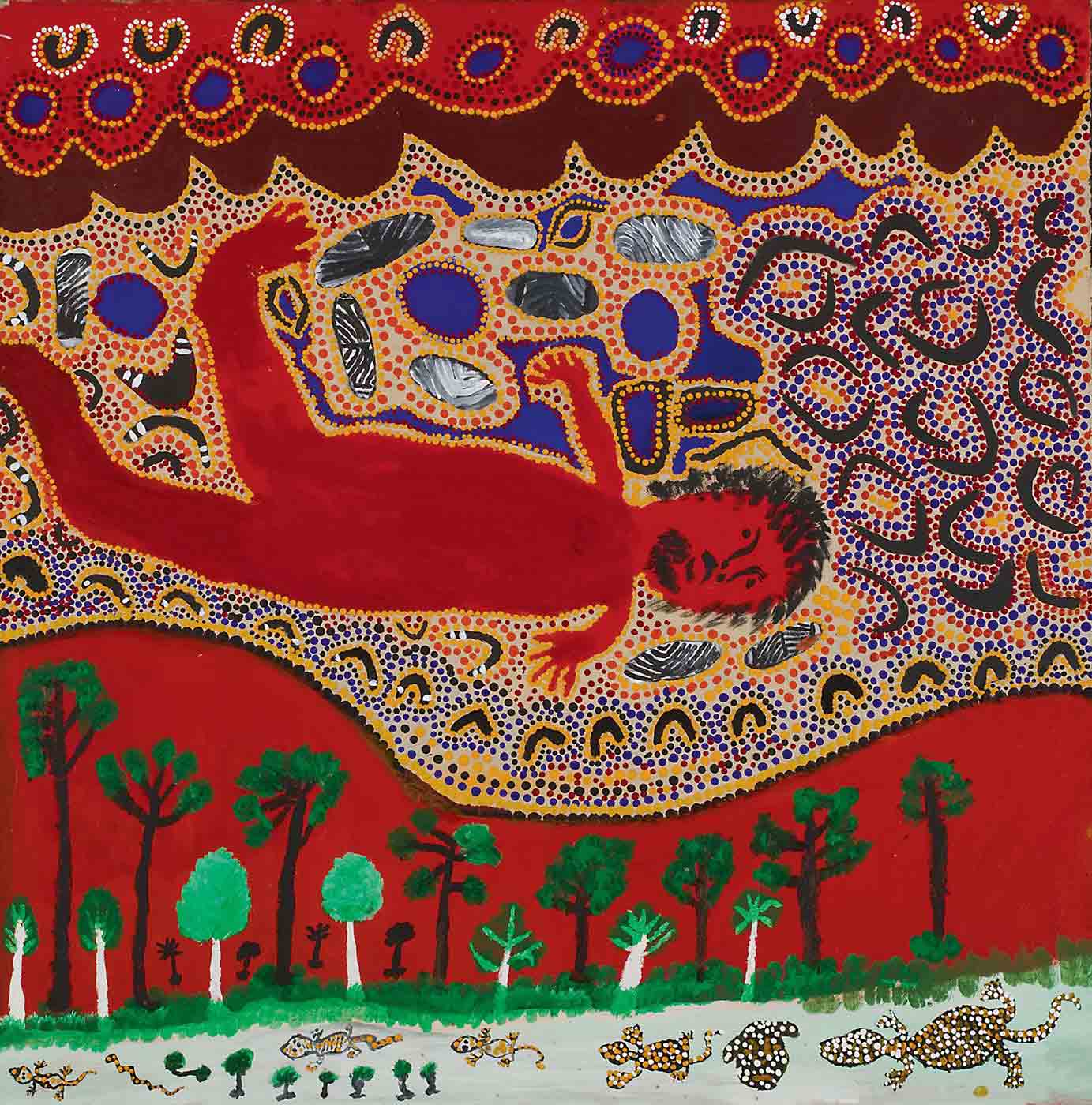

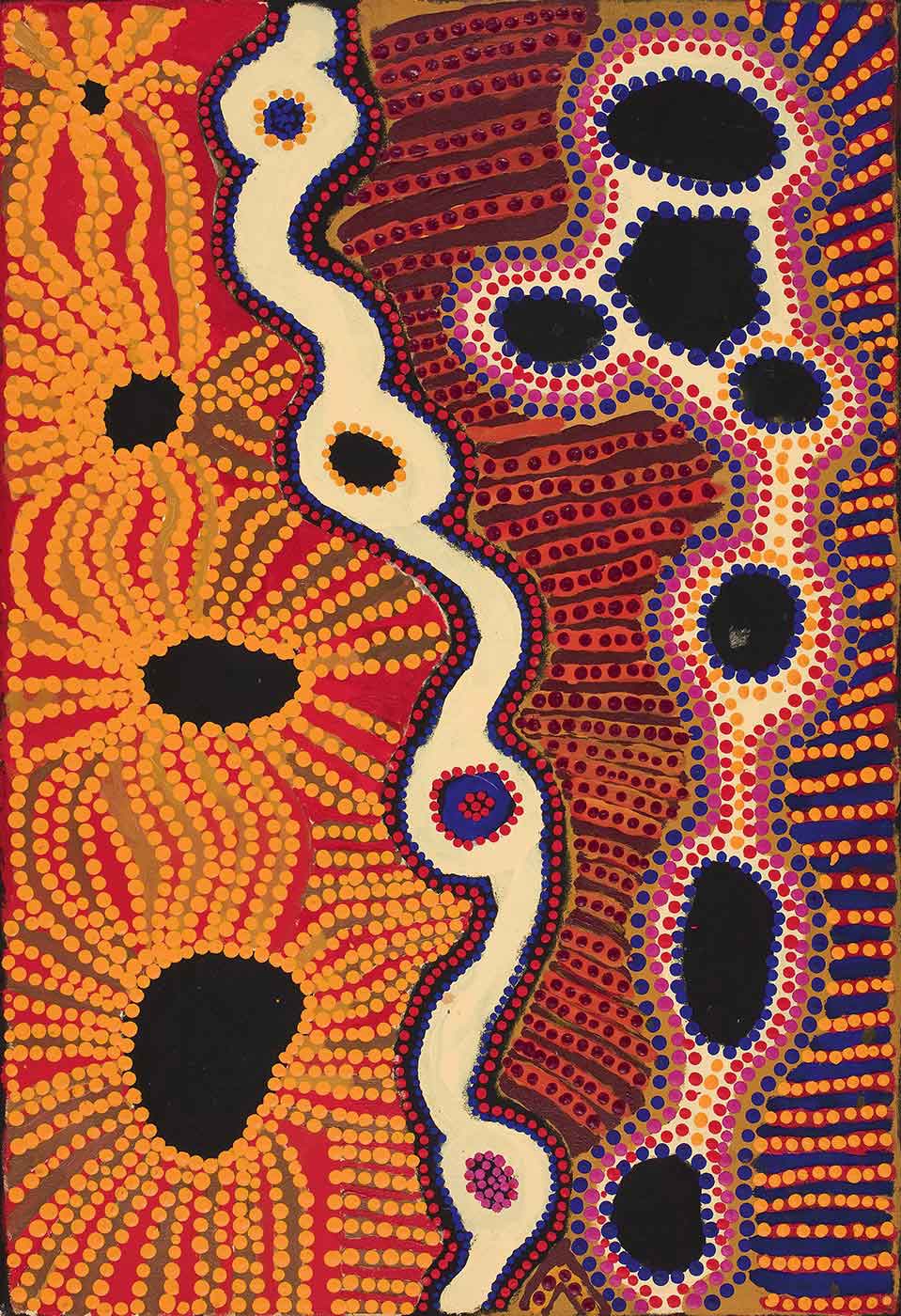

Kumpupirntily by Yanjimi Peter Rowlands

Lake Disappointment by Yanjimi Peter Rowlands

Lake Disappointment by Yanjimi Peter Rowlands

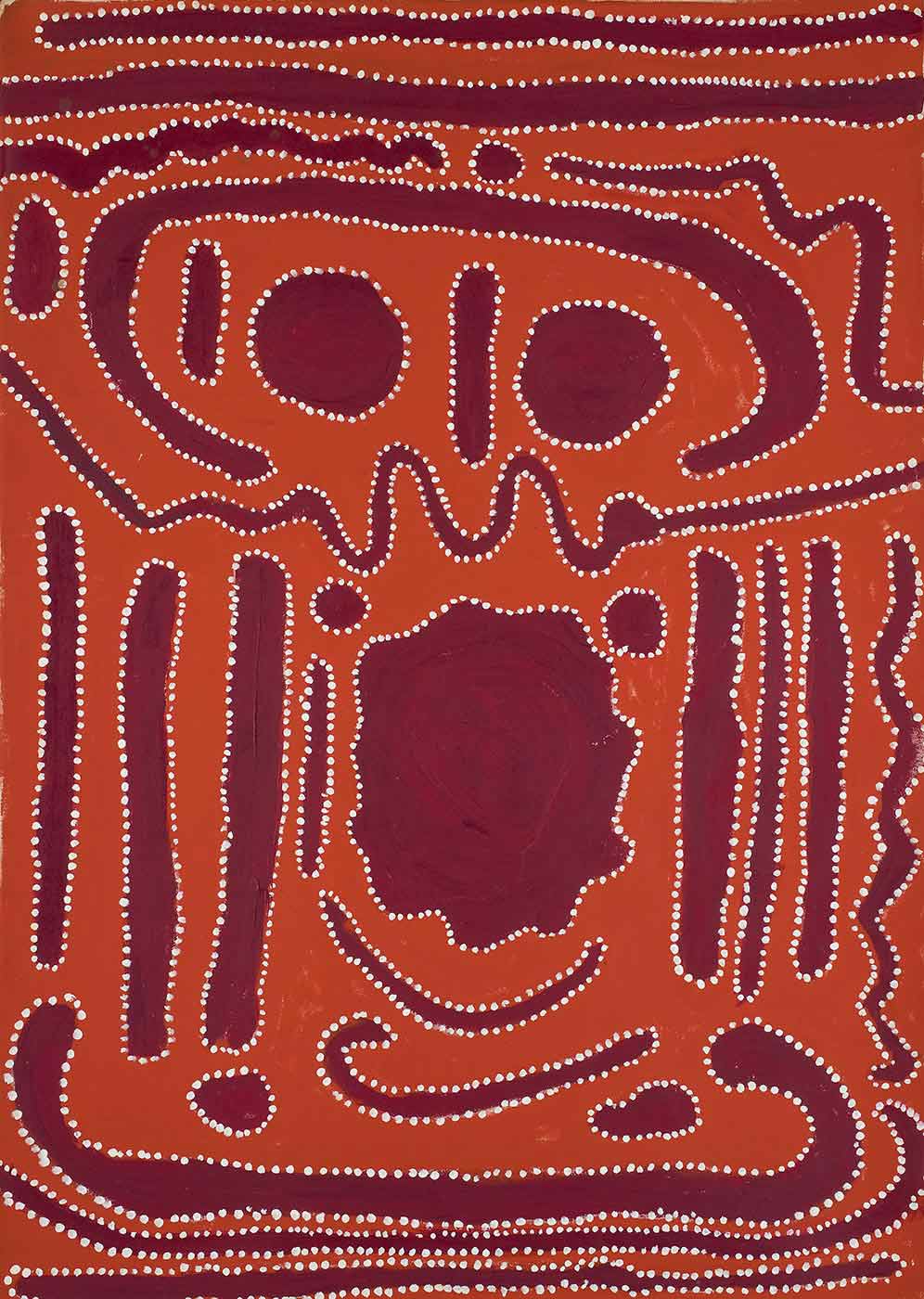

Kumpupirntily by Billy Atkins

Puntawarri, Jilakurru and Kumpupirntily by Dadda Samson and Judith Samson

Explore more on Yiwarra Kuju