Jakayu Biljabu, Parnngurr, 2008:

Now we make lovely baskets in bright and earthy colours.

Acrylic paintings are only one part of the Canning Stock Route collection, and one of the most recent expressions of desert people’s innovative traditions. Indeed, the Museum’s acquisition of art and material culture is not even the first ‘Canning Stock Route collection’.

During the survey of the stock route in 1906–07, Alfred Canning and his men collected various items of Aboriginal people’s material culture as ethnographic curios, including boomerangs, spears and sacred boards. (Canning’s cook, Edward Blake, later accused the party of ‘unfairly’ acquiring some of these items.)

When Canning went back to recondition the stock route wells in 1930–31, the Western Australian and South Australian museums arranged for an ornithologist and taxidermist, Otto Lipfert, to accompany him for the purpose of making official collections.

The usual objects of ethnographic curiosity – coolamons, spear-throwers, shields, pearl shell, throwing sticks, sandals and boomerangs – were acquired from desert people as a record of their ancient technologies.

Yet today these objects tell another story: they cast a light on the innovations in material culture continually made by Aboriginal people as they responded to new influences, materials and ideas.

The ill-conceived placement and construction of Canning’s wells made many traditional water sources inaccessible to Aboriginal people. Aboriginal people responded by destroying the wells, part of their attempt to prevent the return of the white men who were colonising their land.

But they also did something else, as William Snell, who set about reconditioning the wells in 1929, reported: they creatively incorporated the well materials into desert life by fashioning pieces of metal and wood into everyday items, such as digging sticks and coolamons.

At Well 28, Snell noted in his diary, ‘the troughing and rope was carried away. Some of the troughing forms their camp several miles to the east’. This creative absorption of new materials is not limited to domestic uses. Snell also noted that people had begun drawing or painting on the well lids themselves.

A metal coolamon was recently discovered near Kalypa (Well 23) by Martumili artists Wokka Taylor and Yanjimi Peter Rowlands. It appears to have been made out of well troughing, the metal edges having been folded over to create a rounded lip. Martumili artist Ngamaru Bidu subsequently recognised the object as having been made and used by her parents.

In the desert, coolamons made of wood, known as piti and ngurti, were among a woman’s most important possessions. Deep bowls were used for carrying water and food, and for soaking medicinal plants; shallower dishes were used for separating seed and as cradles for newborn babies. Smaller coolamons also served as tools for digging and clearing.

The colourful baskets woven by Martu women today recall these vessels.

Nola Taylor, Parnngurr, 2008:

We design baskets to remind us of the piti [wooden dishes] we used to carry on our heads. We gather the minari [grass] from our own Country and we like lovely coloured wool.

Another coolamon, collected by Canning’s party in 1930–31, is so roughly hewn it looks as if it had dropped off a tree, but the fluting along its inner surface suggests a convention that emerged in Western Desert material culture through contact with Central Australian traditions. This aesthetic approach to even the most elementary technology reminds us that these objects are part of the enduring and dynamic artistic traditions of the region.

Canning also collected various other items from desert people, both during the first survey in 1906–07, and again when he returned 25 years later.

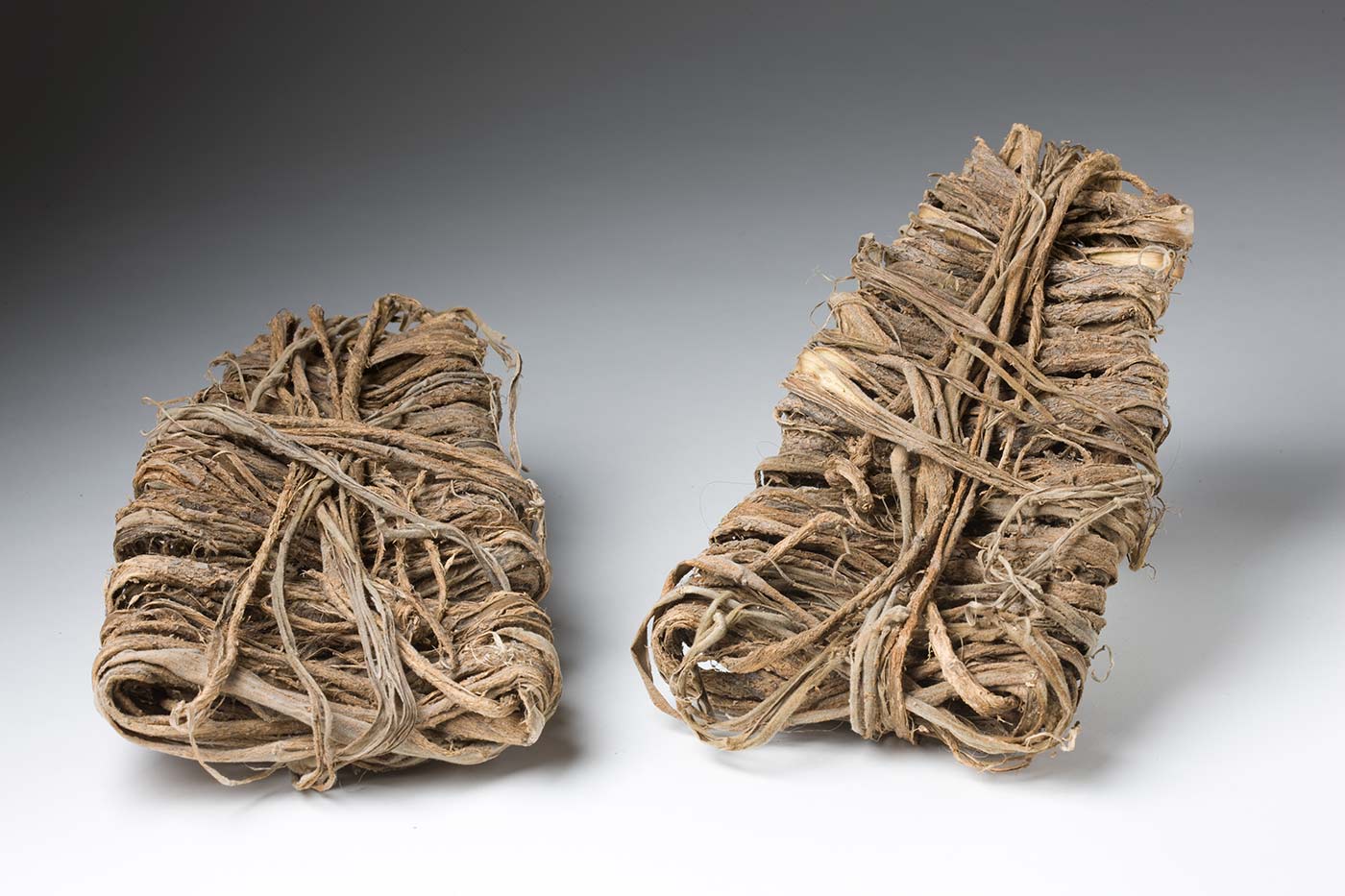

Worn as protection against desert sands, scorched to more than 45°C by the summer sun, yakapiri (woven bark sandals) are unique to the peoples of the Western Desert. They are usually made from the tough inner bark of the yakapiri or ‘bird plant’, which grows in sandy areas over much of the Western Desert.

Women also wore woven manguri (head pads) to cushion the weight of water, food and other items carried in wooden coolamons.

Yuwali Janice Nixon, Parnngurr, 2008:

I was away when they started making baskets. I came home to Jigalong and watched my sister-in-law and she taught me. It was really nice. I used to watch Yikartu Bumba and Kumpaya; they really love making baskets. Nalda Searles came to Parnngurr and we coiled baskets all night and all day. All night and all day – no sleep in Parnngurr! Kumpaya, you have to talk because you brought this good idea to us.

Kumpaya Girgaba, Parnngurr, 2008:

When I was in Kurungal [Wangkatjungka] I was learning to make baskets. I learned how to make baskets before I started making painting. It’s like weaving manguri [head pads].

Desert shields were used principally during fighting and ceremonial occasions. An integral part of male hunting technology, spear-throwers were used to launch spears with great speed and accuracy. The designs engraved on the weapons made them powerful.

Certain styles of engraving entered the Western Desert from Central Australia and from the coastal people to the west. They reveal longstanding trade routes and cultural interactions.

Innovations in material culture continue to be made. Desert women produce a variety of woven forms that fuse traditional weaving techniques with the wooden vessels so vital to their cultural life.

Such baskets are made from coiled desert grasses wound with brightly coloured yarns that reveal subtle variations. Some are even constructed on the metal bases of tin cans, or embellished with beads, their shapes and design evolving in step with the imagination of their makers.

Today the most important innovation occurs in the realm of ceremonial activity – the dances, songs and ritual items that are central to desert culture. Ceremonies arising from the Jukurrpa are performed to revitalise both the desert people and their Country.

But Aboriginal people today also create new songs, dances and ceremonial materials; these are drawn from dreams and from the stories that are critical to the historical and cultural identity of desert people.

Putuparri Tom Lawford, Fitzroy Crossing, 2008:

Old people were happy because all the young ones been dancing and learning artefact making and collecting materials for ceremony. They been passing down to their grandkids so they can carry on that dancing.

Explore more on Yiwarra Kuju