The first sustained encounter the Yolngu had with Ngapaki, or Europeans, began in 1935 with the establishment of the Methodist mission at Yirrkala. Because it was on Rirratjingu land, the Marikas became major players in all subsequent events in the region. Art played a critical part in these interactions.

When Wilbur Chaseling encouraged the commercial sale of bark painting, Mawalan 1 Marika and other Yolngu used this opportunity to present their ancestral narratives to a non-Indigenous audience.

This type of cultural brokerage was evident in the artists' subsequent work with anthropologists and collectors and was the motivation behind the famous Yirrkala church panels and the Yirrkala bark petitions.

Church panels

Between 1962–63 artists from various clans collaborated to paint the ancestral narratives of their respective Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties on two three-metre high masonite panels.

Almost half of the Dhuwa panel depicts the Djang'kawu episodes at Yalangbara by Mawalan 1, Wandjuk and Mathaman Marika. The panels that were originally mounted on either side of the church altar were a political assertion of Yolngu religion and land ownership. They were also a response to the threat of mining activity on Rirratjingu and Gumatj land and became the model for the famous Yirrkala bark petitions.

Yirrkala bark petitions and land rights

In 1963 the government approved the excision of Rirratjingu and Gumatj land for the Nabalco bauxite mine, despite opposition from the mission and the land owners.

In a bid to have their land rights recognised, Mawalan and other Yolngu representatives sent a bark petition edged by their clan patterns with text translated and typed by Wandjuk Marika, to the Federal House of Representatives.

This was followed later by another similar petition in 1968. By then Mawalan 1 Marika had passed away so it fell to his successors – Mathaman, then Milirrpum – to continue the struggle. This began in 1968 with the first major land rights case Mathaman v Nabalco Pty Ltd that continued after his death as Milirrpum and Others v Nabalco Pty Ltd and the Commonwealth of Australia.

Although the Yolngu were unsuccessful in having their land rights recognised on this occasion, the case was a catalyst for the eventual passing of the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act in 1976.

A year later the Rirratjingu presented one of their Djang'kawu digging sticks to the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs to celebrate the final acknowledgement of their land rights. This exhibit, which is part of the Yalangbara exhibition, is normally displayed alongside the Yirrkala bark petition in Parliament House.

Copyright and the carpet case

The next important issue that was spearheaded by the Marika family was recognition of Indigenous copyright.

It was instigated by Wandjuk Marika after he found his sacred Yalangbara designs reproduced without permission.

Some time ago I happened to see a tea towel with one of my paintings represented on it ... I was deeply upset and for many years I have been unable to paint. It was then that I realised that I and my fellow artists needed some sort of protection. It is not that we object to people reproducing our work, but it is essential that we be consulted first, for only we know if a particular painting is of special sacred significance.

It was due to Wandjuk's advocacy as Chairman of the Australia Council's Aboriginal Arts Board, that the Council established the Aboriginal Artists Agency (AAA) in 1976 specifically to monitor unauthorised reproductions and obtain royalty payments for Aboriginal artists.

Since this time, Indigenous artists have used the existing Copyright Act to pursue a number of copyright infringements of their artwork.

In 1993 Wandjuk's sister, Dr B Marika AO, was involved in one of the most successful cases regarding Indigenous copyright in Australia.

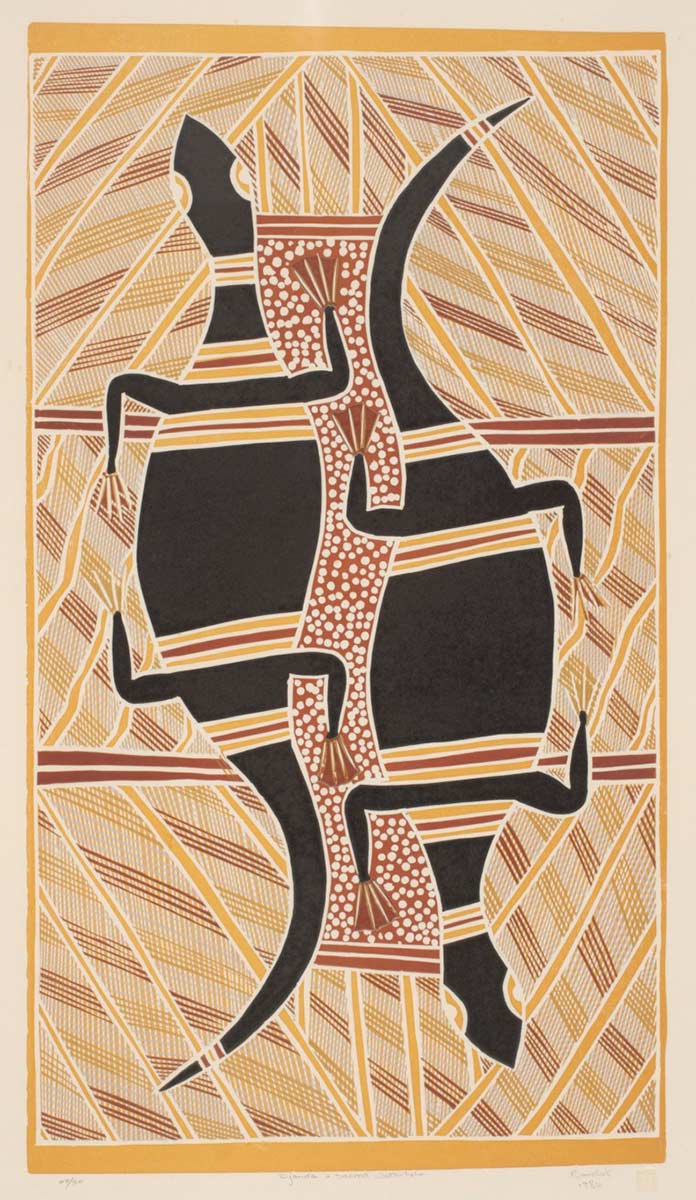

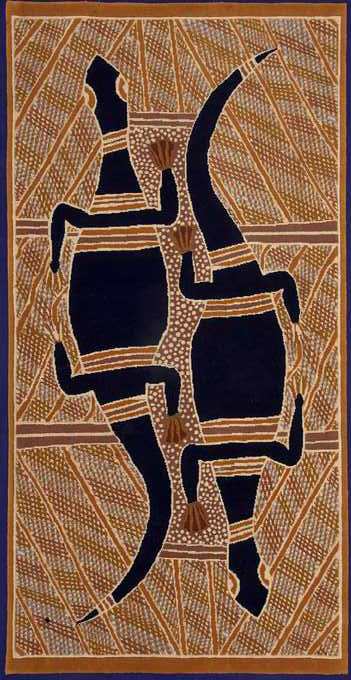

It involved an Australian company which had reproduced woollen carpets with the unauthorised artwork of eight Aboriginal artists, including a Yalangbara-based print by Dr B Marika AO, Djanda and the Sacred Waterhole.

Dr B Marika AO, along with the other two living artists involved, George Milpurrurru and Tim Payungka Tjapangarti, sought reparation for breaches under the Copyright Act and the Trade Practices Act.

In a landmark decision in 1994, the Federal Court ruled in favour of the artists and awarded the largest award for an infringement of an Australian artist's copyright.