The Art of Science: Baudin’s Voyagers 1800–1804 featured illustrations of Australian animals and marine life, as well as striking portraits of Aboriginal people, rare documents and hand-drawn maps from Nicolas Baudin’s expedition to Australia.

The Art of Science was previously on show at the National Museum of Australia from 30 March to 24 June 2018.

Exhibition highlights

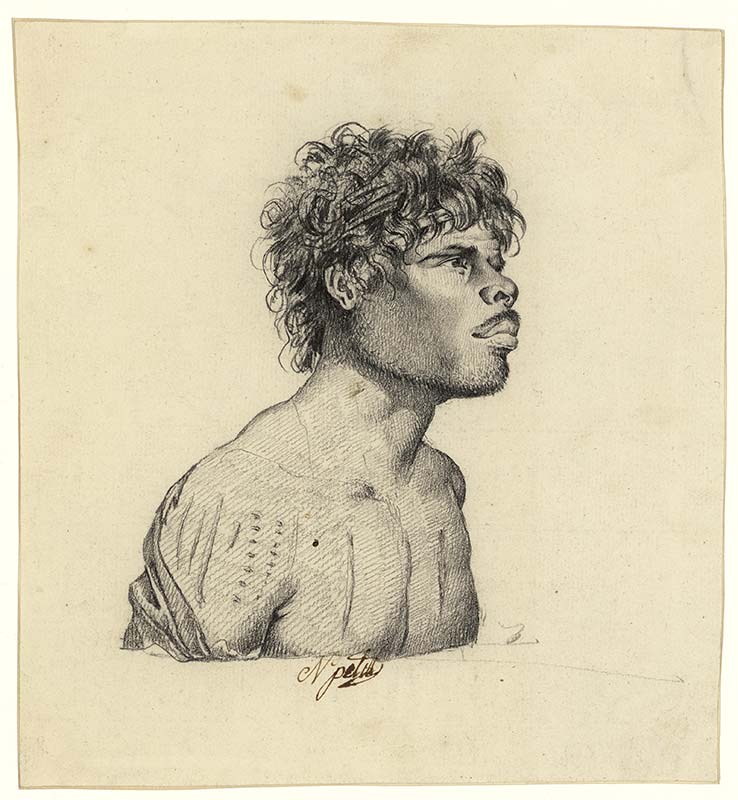

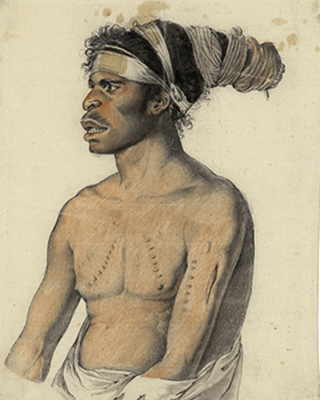

A New Holland man by Nicolas-Martin Petit

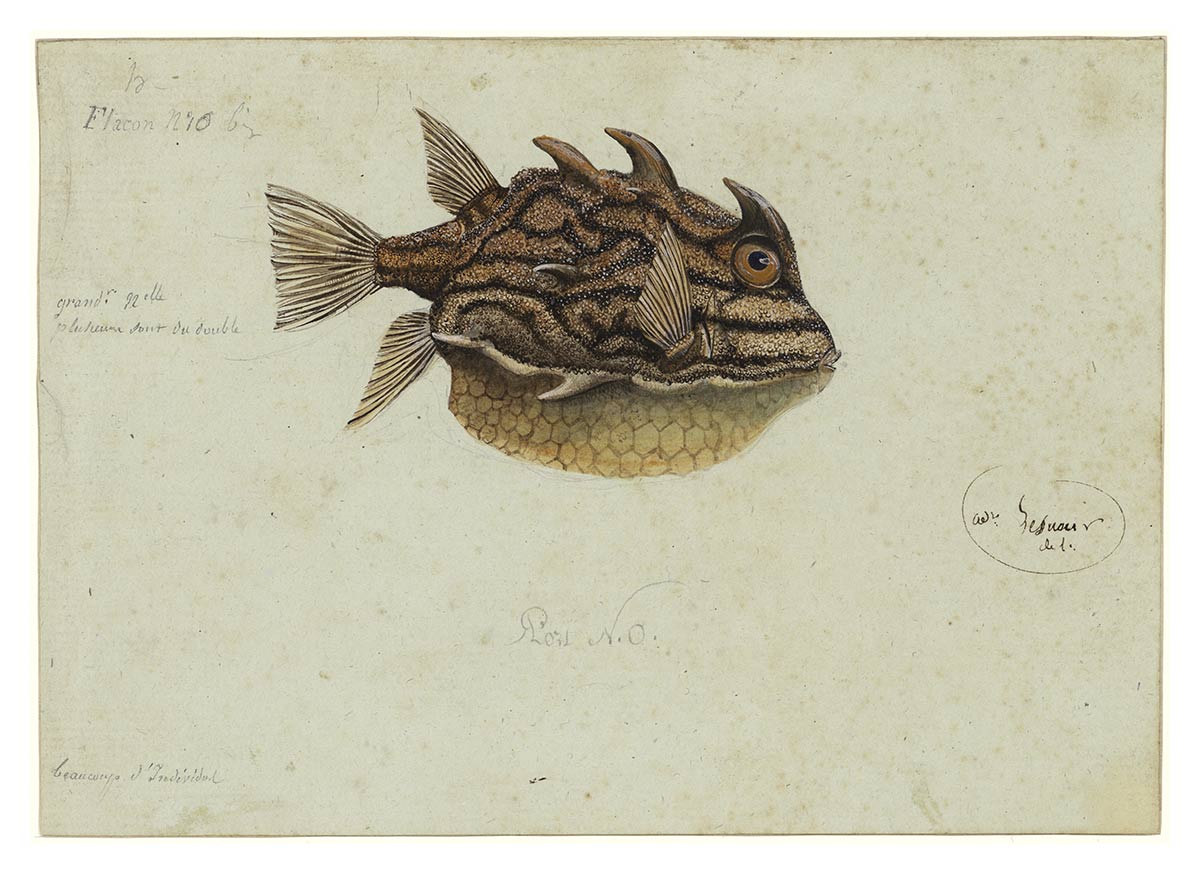

Cowfish – Aracana sp. by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Emu – Dromaius sp. by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Starfish – Archaster angulatur by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Canda returning from the fountain by Nicolas-Martin Petit

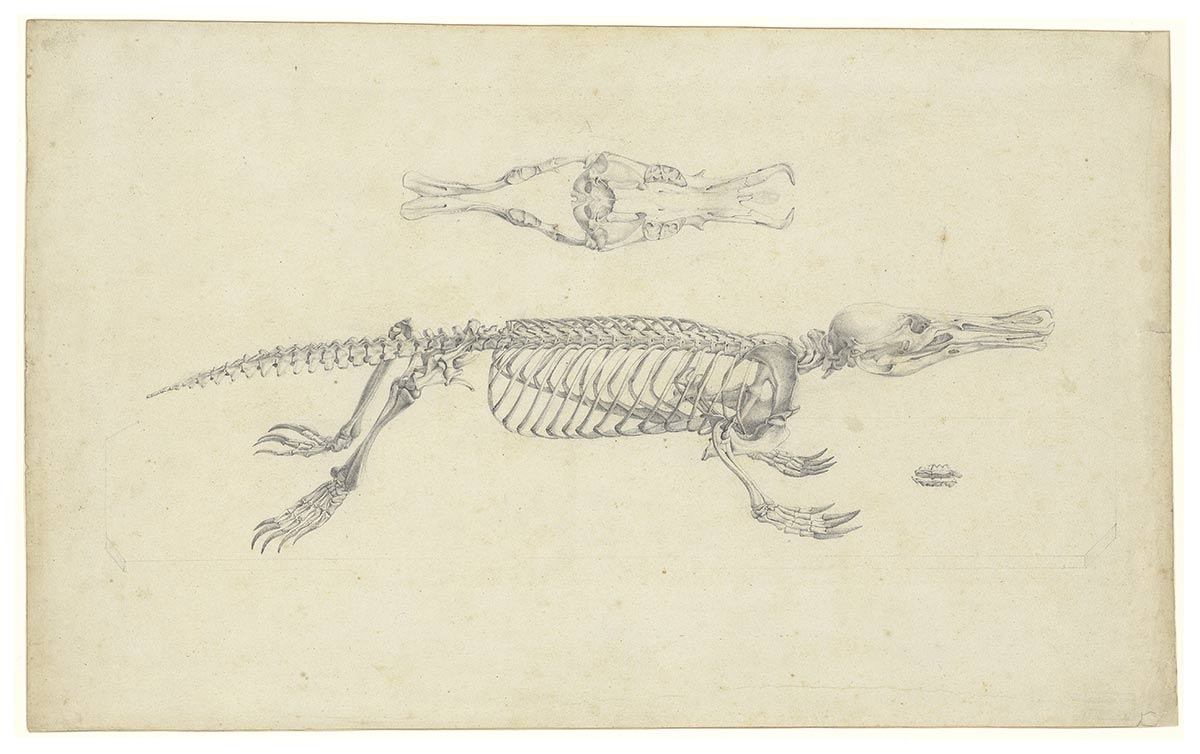

Skeleton of platypus – Ornithorhynchus anatinus by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

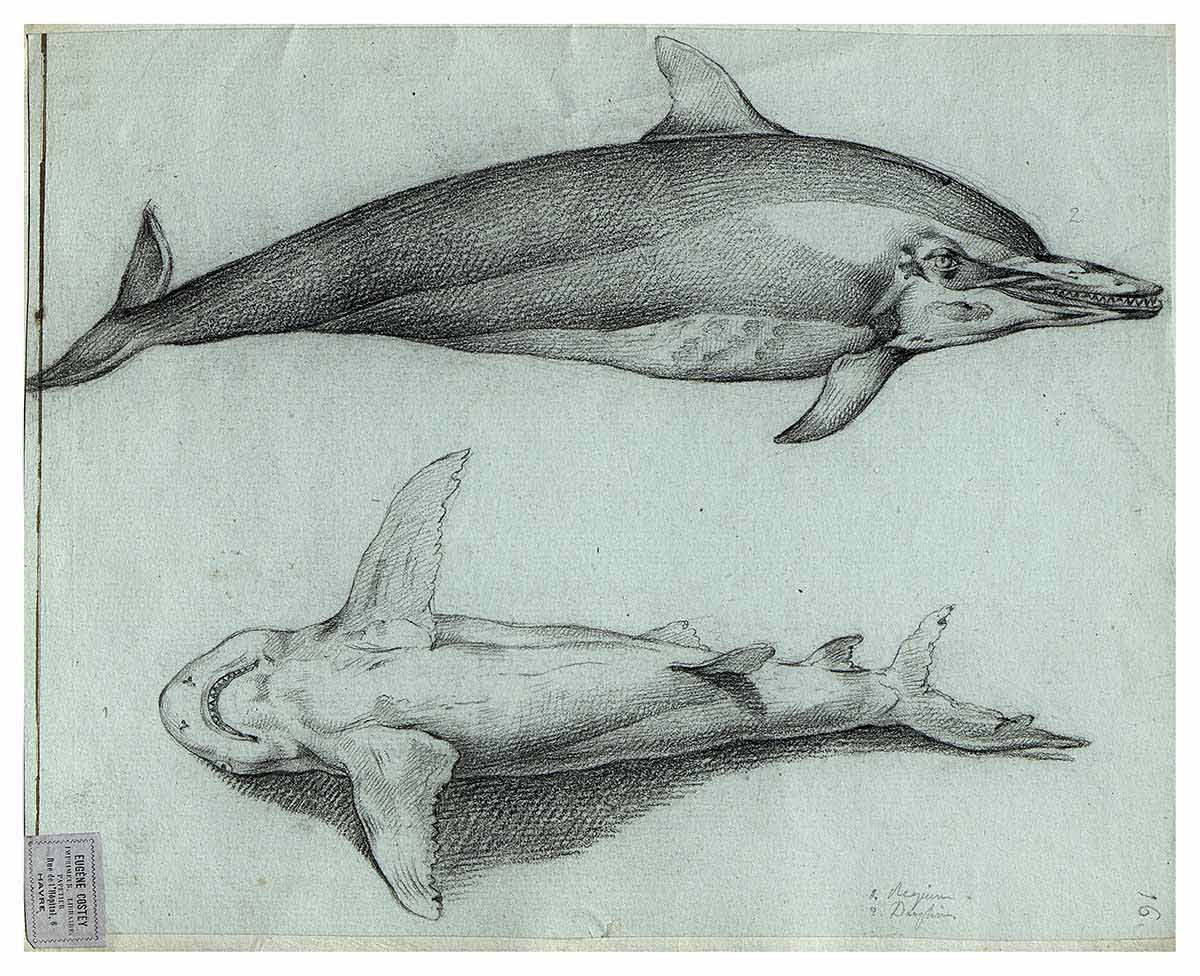

Profile of a dolphin and ventral view of a shark, attributed to Louis Lebrun or Jacques-Gérard Milbert

Bluebottle fish – Nomeus albula by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

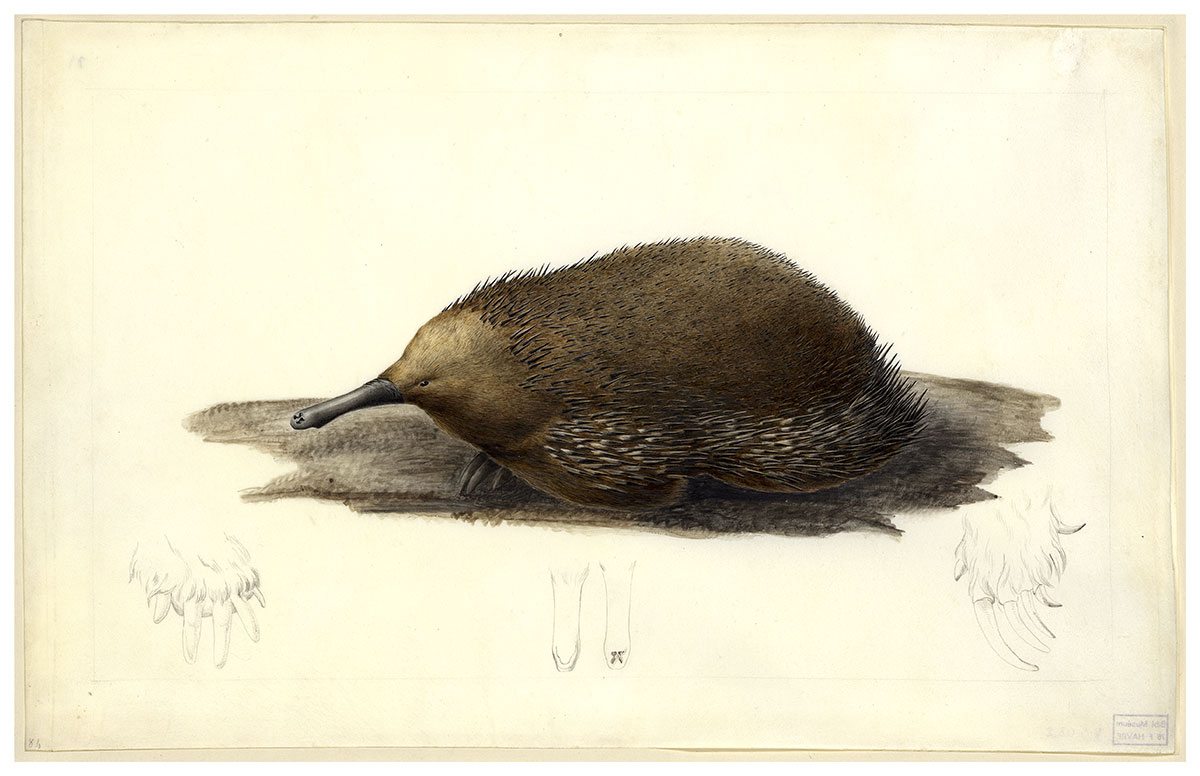

Short-beaked echidna – Tachyglossus aculeatus setosus by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

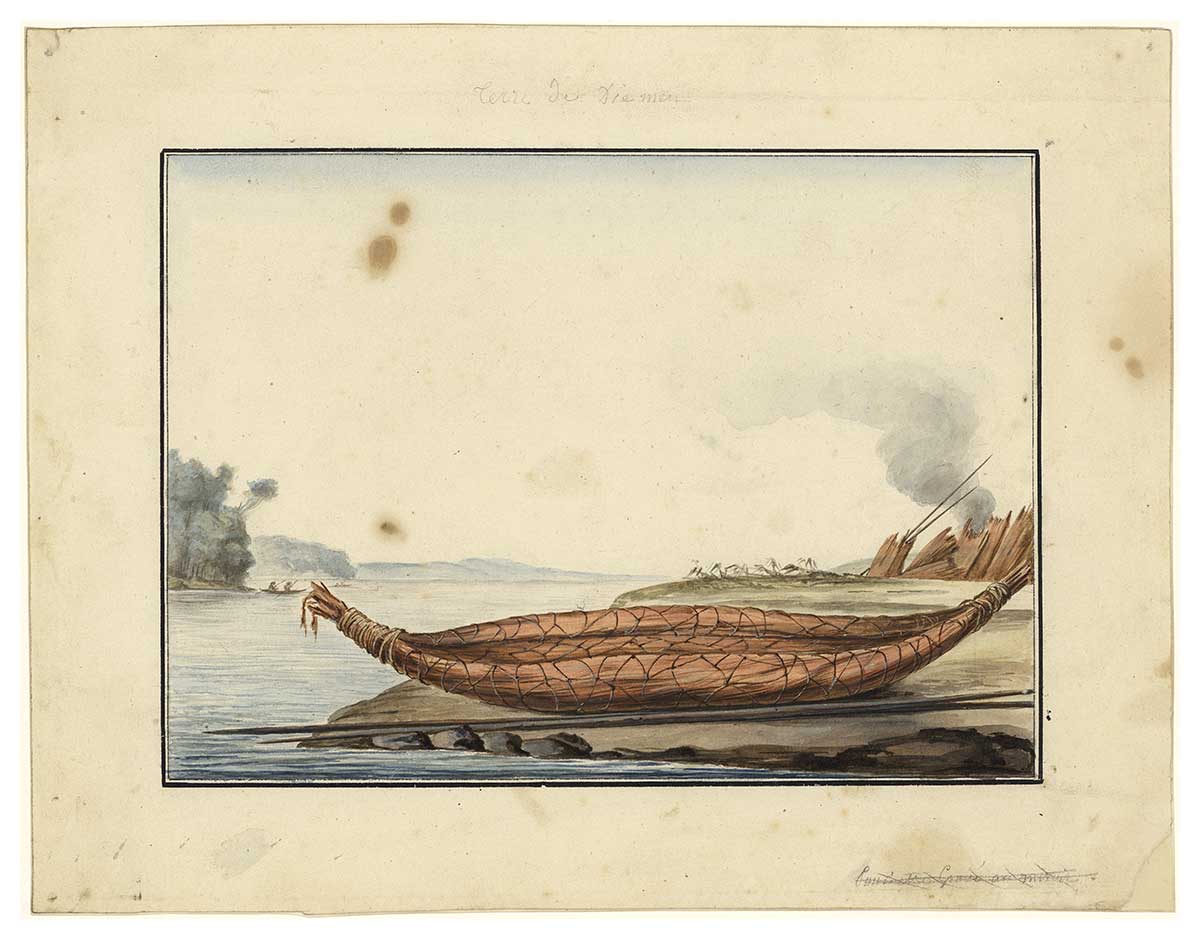

Ninga (bark canoe) with spears by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur or Nicolas-Martin Petit

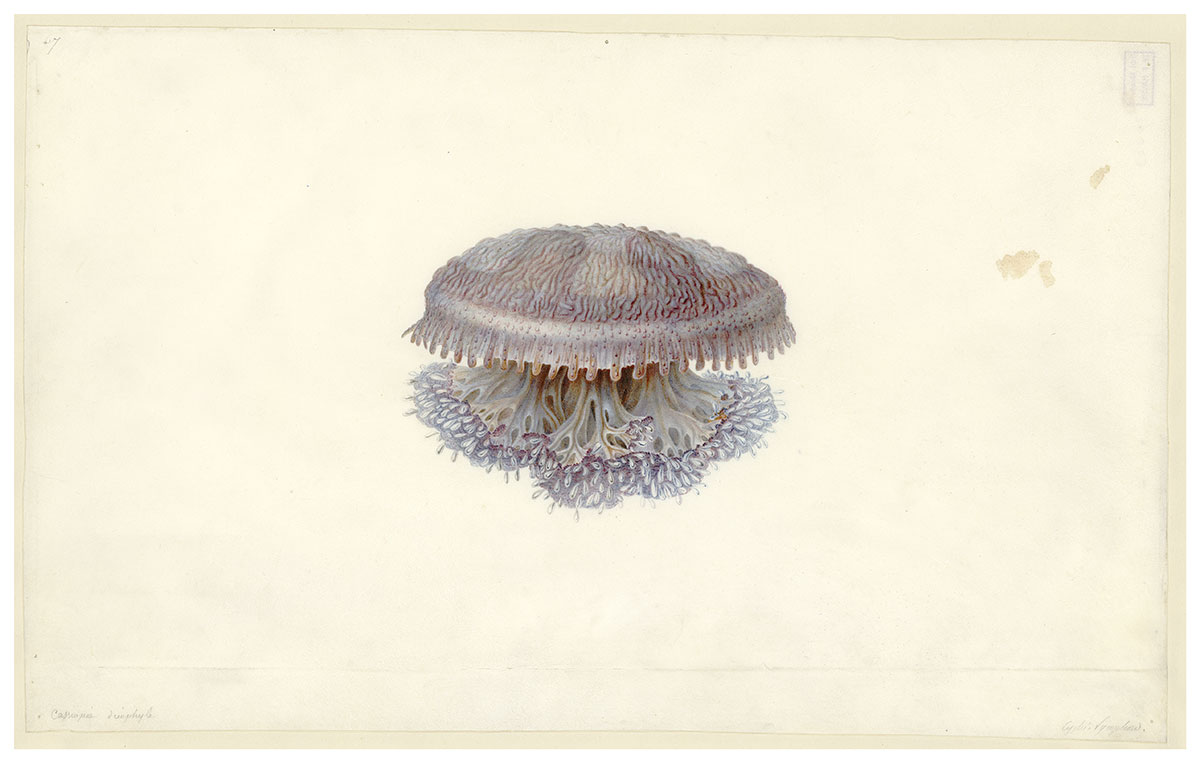

Jellyfish – Cassiopea dieuphila by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

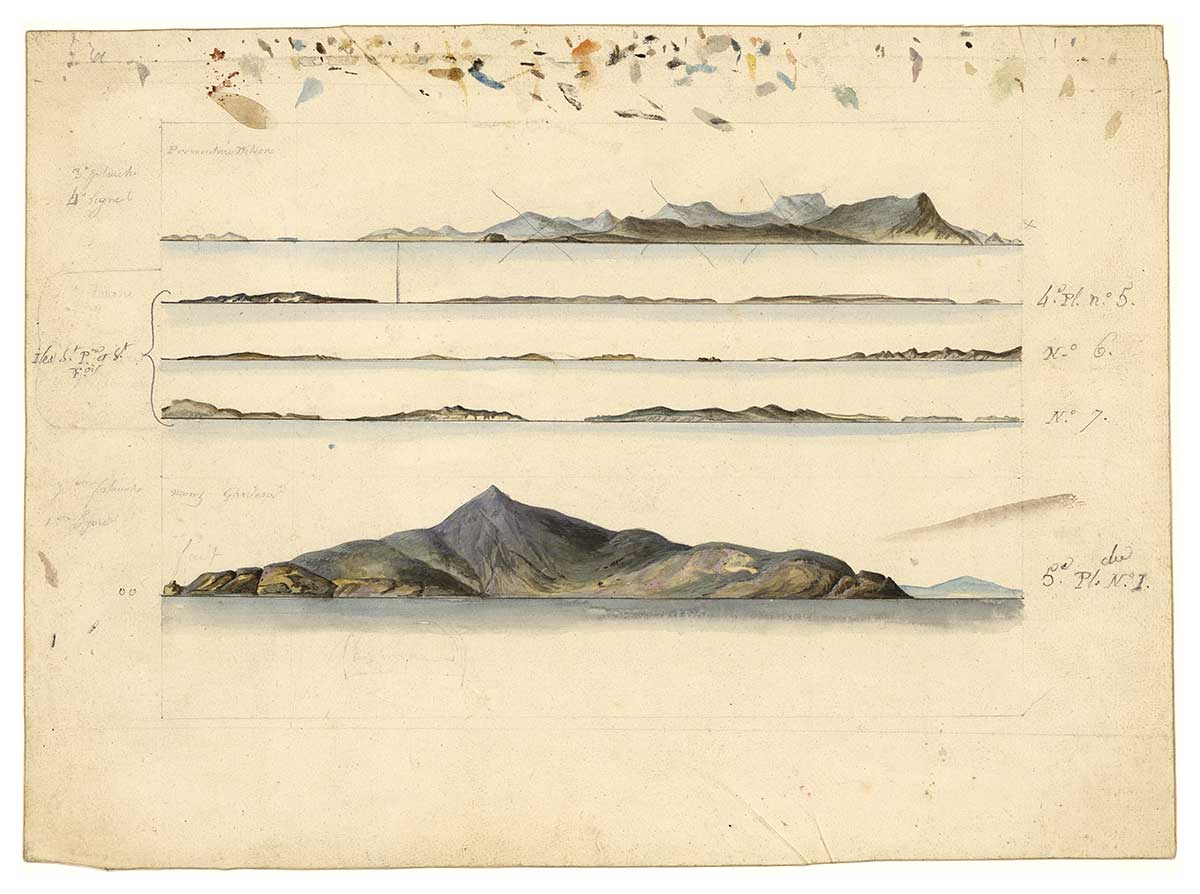

Five coastal profiles including Wilson's Promontory (Victoria) and Nuyts Archipelago (South Australia) by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Gastropod shell – Conus miles by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

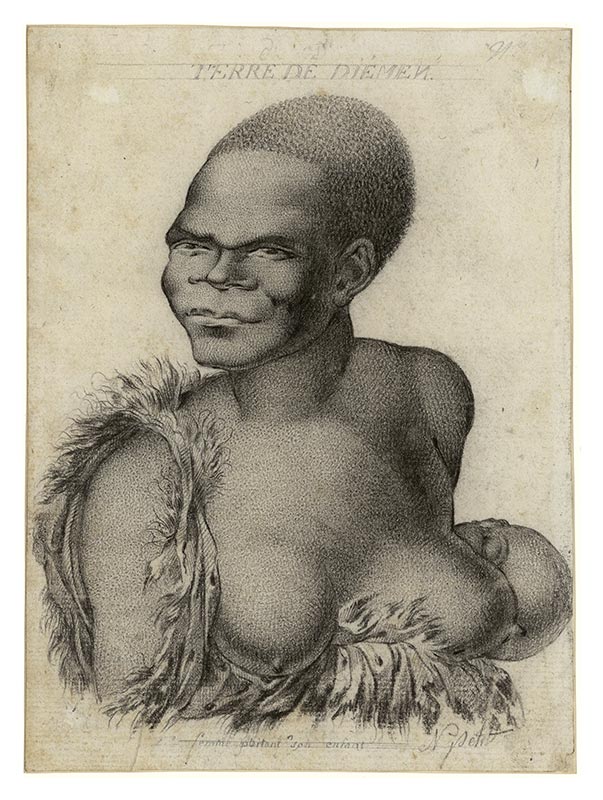

Arra Maïda carrying her infant child by Nicolas-Martin Petit

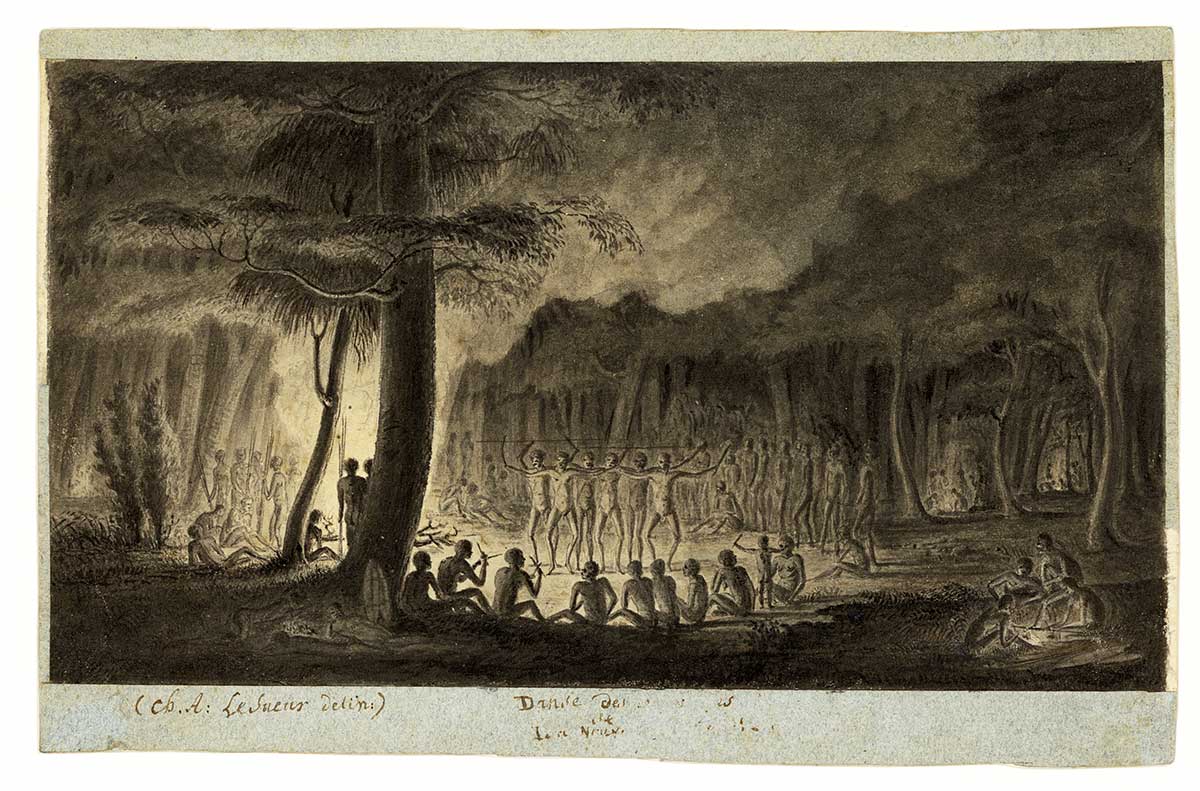

Aboriginal people dancing near a fire by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

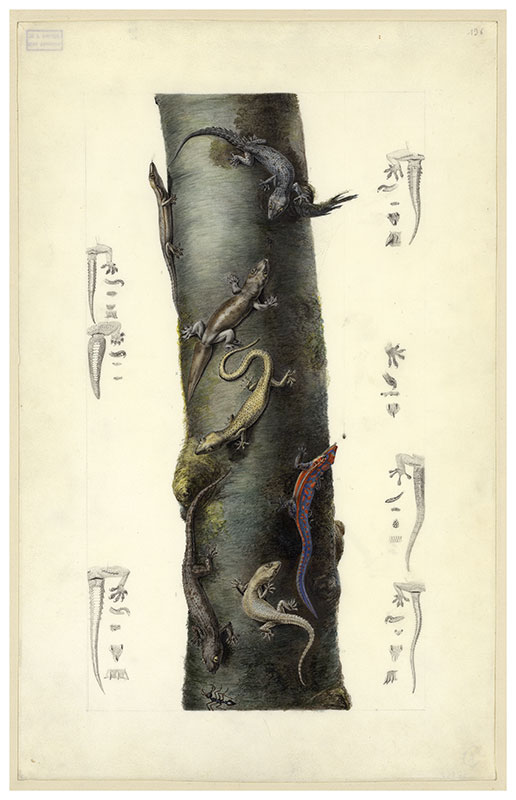

Lizards from Australia and the Indian Ocean by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Shell necklace by Lola Greeno

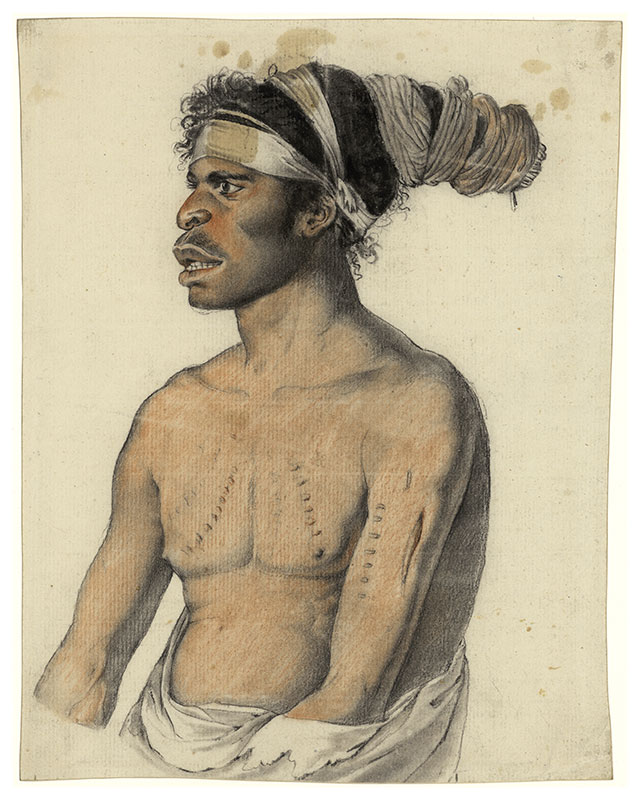

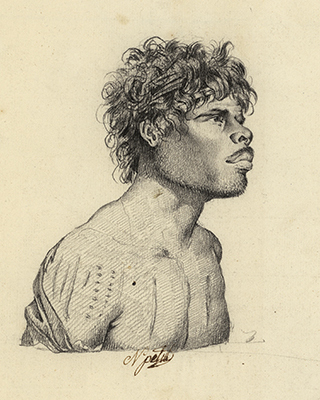

Eora man Mororé by Nicolas-Martin Petit

Model paperbark canoe by Rex Greeno

Baudin's expedition embodied the Enlightenment’s hunger for knowledge. National Museum curator Cheryl Crilly wrote for The Museum magazine about the remarkable works created by Baudin’s artists, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit, and what they reveal about the sense of wonder that this strange ‘new’ world inspired.

Art, science and discovery

In 1800 Nicolas Baudin led two ships carrying 22 scientists and more than 230 officers and crew on a three-and-a-half-year voyage to the ‘Southern Lands’. Embodying the Enlightenment’s hunger for knowledge, the expedition studied the natural environment, recorded encounters with Indigenous peoples and published the first complete chart of Australia.

Baudin’s artists, Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit, painted remarkable portraits of Aboriginal people, and produced some of the earliest European views of Australian fauna and marine life. Their artworks reveal the sense of wonder that this strange ‘new’ world inspired.

Blue sea slug — Glaucus atlanticus (detail), Caper white butterfly — Belenois java teutonia (detail), starfish — Archaster angulatus (detail) by Charles Alexandre-Lesueur

Expedition

Captain Nicolas Baudin’s scientific expedition to map the ‘unknown’ coast of Australia is a complex and fascinating narrative that rivals any fictional tale of exploration set on the high seas. The voyage took three-and-a-half years and is a remarkable story of political tensions, class division, fanatical collectors, desertion, death and thwarted colonial ambition, as well as scientific discovery and artistic creation.

The Géographe and Naturaliste were lavishly fitted out for the expedition and included a library and an extra deck to house the scientists, live animals and plants. The ships were crammed with cases of scientific equipment and crates of barter items such as mirrors, buttons, scissors, earrings, combs and ribbons.

On board were more than 230 officers and crew, three official artists, five gardeners and 22 scientists, including two mineralogists, three botanists, six zoologists and two geographers. Zoologist François Péron and cartographer Louis de Freycinet would later pen the official account of the expedition.

Tensions on board festered in the six months it took to reach the first landfall in Mauritius. Baudin, a man of modest birth, was disliked, even despised, by officers and scientists alike. Ten scientists and 46 crew jumped ship, setting the tone for what would be a long and difficult voyage.

Baudin’s ships Géographe and Naturaliste set sail from Le Havre, France on 19 October 1800, in pursuit of geographical and scientific knowledge. It was a time of great political, cultural and social change in France, with new ideas and philosophies underpinning the ideals of the French Revolution. Religion and superstition were being replaced by science and reason and theories on the rights of man.

Fascinated by voyages of scientific discovery and driven by a hunger for knowledge – and the power it could wield – First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte authorised and generously funded Baudin’s expedition to chart New Holland’s ‘unknown’ southern coast, study the natural environment, and record encounters with Indigenous peoples.

Baudin’s ships finally reached Australia in May 1801, arriving at Cape Leeuwin, Western Australia. Despite escalating tensions between Baudin and his savants (learned scientists), and a crew ravaged by scurvy and dysentery, the expedition achieved two surveys of the south and west coasts. It charted almost two-thirds of the Australian coastline and collected a vast array of animal and plant specimens. The French spent 10 weeks exploring Tasmania, charting the east coast and frequently interacting with Tasmanian Aboriginal people.

Encounters

France and Britain were at war during Baudin’s voyage and, although scientific endeavour transcended national borders, the expedition had to request a passport for safe conduct for its ships and crew. In doing so, they alerted the British to their intentions and the Investigator, captained by Matthew Flinders, was sent to Australia.

In April 1802 Géographe and the Investigator crossed paths at what is now Encounter Bay in South Australia, and Baudin learnt that the British had beaten him to charting the southern coast. At Port Jackson several months later, the captains of both expeditions shared charts and observations.

Henri de Freycinet, Louis’ brother and an officer on the voyage, told Flinders, ‘If we had not been kept so long picking up shells and catching butterflies in Van Diemen’s Land, you would not have discovered the South Coast before us.'

Captain Baudin died of tuberculosis in Mauritius in 1803, on the journey back to France. By the time the expedition returned, the focus had shifted to the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and interest in the southern lands had waned. François Péron and other scientists tarnished Baudin’s reputation, emphasising the disasters and disappointments and the failure to chart the southern coast.

Napoleon was rumoured to have said Baudin did well to die in Mauritius, for he would have hanged him had he returned to France.

Collections

Despite the political turmoil in Europe and Baudin’s blackened name, the expedition was a triumph for science, returning with over 100,000 specimens and more than 2,500 new species. The scientists’ perseverance and zeal produced a rich scientific haul as they strove to classify and ultimately tame the natural world.

Péron was an insatiable collector, often disobeying instructions and risking his safety to gather specimens. He and the other savants amassed an extensive collection of flora and fauna that was meticulously documented by Péron, who noted the dates and places of capture, along with other details for each specimen.

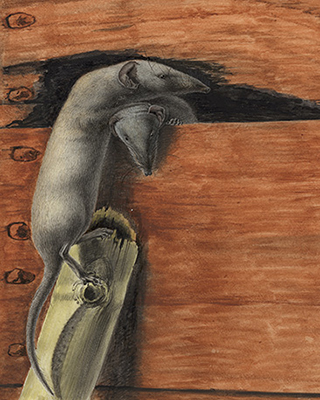

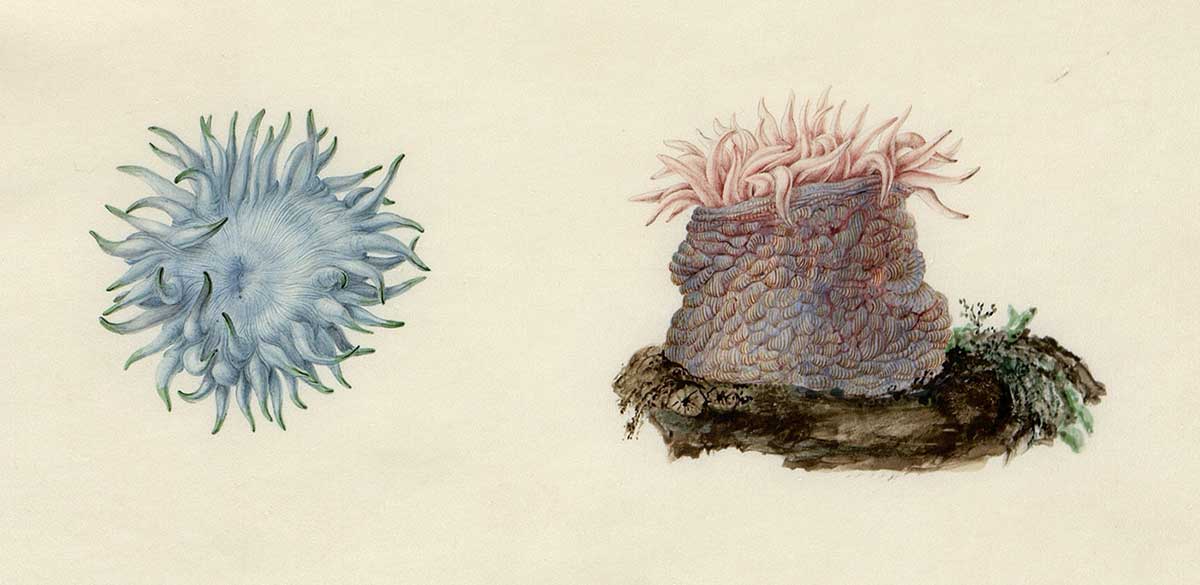

Marine life was an obsession of the expedition, and the ocean was where the scientists made their greatest discoveries. They were fascinated by the strange and beautiful marine creatures they scooped from the sea, and discovered 18 new species of jellyfish. The specimens had to be stored in alcohol, with Péron and Lesueur often sacrificing their own rum rations to preserve the collections. Much of the marine life was dissected and sketched on deck, including several dolphins that were later served up to a malnourished crew in a ragout.

Collections of live animals were also taken on board and the ships became floating menageries. Baudin was determined to return to France with an impressive live cargo and officers were evicted from their cabins to make space for kangaroos, emus, wombats, tortoises and caged birds.

Water rations were reduced, so no animal went thirsty. When the kangaroos and emus became seasick and stopped eating, they were force-fed wine and rice mash. The ship stank of animals and rotting marine specimens. Seventy-two animals survived the voyage and many lived out their days in the Empress Josephine Bonaparte’s menagerie at her Paris retreat, Château de Malmaison.

Artists

The ships were overcrowded with scientists, equipment and the immense collections, yet Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit found the creative space to produce a remarkable legacy of the expedition.

Although both men were registered as assistant gunners for the voyage, they had been engaged by Baudin to illustrate his journal. When the three official artists deserted the expedition at Mauritius, Lesueur and Petit were promoted, going on to create over 1,500 drawings and paintings that are among the most historically important and beautiful records of 19th-century discovery.

As the voyage unfolded and Lesueur worked closely with naturalist Péron, his illustrations of birds, animals and marine creatures became more ambitious and scientifically accurate. Among the most impressive are his watercolours of elusive jellyfish and other marine invertebrates. These diaphanous and gelatinous specimens were impossible to preserve, and Lesueur’s watercolours were the only way to capture their true form and colour.

While Lesueur illustrated the natural world, Petit focused on the people encountered during the voyage. He created a series of fine portraits of Aboriginal people from Tasmania and Port Jackson, many of whom are identified by name.

The portraits are beautiful, strong and sensitive portrayals, offering a rare view of First Australians before the widespread impact of colonial invasion. Objects made and used by Aboriginal people were also illustrated and ‘acquired’ by the voyagers.

Sea anemones — Tealia sp. (detail) by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur

Objects

Baudin's Voyagers includes stunning original illustrations by artists Charles-Alexandre Lesueur and Nicolas-Martin Petit on loan from the Natural History Museum, Le Havre. Although more than 200 years old, these works have a contemporary aesthetic, with bold compositions, rich colours and attention to detail.

Other highlights are Nicolas Baudin’s journal, on loan from the National Archives, Paris, a chronometer from the voyage and the copper plate used to print the first complete map of Australia ever published.

Objects on show from the National Museum of Australia’s collection include a stunning maireener shell necklace by Tasmanian Aboriginal artist Lola Greeno and a first edition copy of the official expedition account, Voyage de Découvertes aux Terres Australes.

'Art, science and discovery' by Cheryl Crilly, Curator, Australian Society and History, National Museum of Australia, extract from The Museum magazine, issue 13, 2018

The Art of Science: Baudin’s Voyagers 1800–1804 is a touring exhibition created through a partnership between the South Australian Maritime Museum (Adelaide), the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (Launceston), the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (Hobart), the Australian National Maritime Museum (Sydney), the National Museum of Australia (Canberra) and the Western Australian Museum (Perth).

The exhibition features illustrations from the Lesueur Collection on loan from the Museum of Natural History, Le Havre, France, and a range of objects from other French and Australian cultural institutions.

The exhibition has been made possible by the generous support of the following partners:

Museum of Natural History, Le Havre, Normandy, France

Presenting partners

Funding partners

This exhibition is supported by the National Collecting Institutions Touring and Outreach Program, an Australian Government program aiming to improve access to the national collections for all Australians.

This exhibition was supported by the Australian Government International Exhibitions Insurance (AGIEI) Program. This program provides funding for the purchase of insurance for significant cultural exhibitions.