Spirited: Australia’s Horse Story explored how horses helped enrich our lives, build our society and shape our environment. It invited Australians to reflect on the enduring and sometimes complex relationships between people and horses.

Introduction of horses

Horses arrived in Australia in January 1788 with the first British colonists, who had purchased at least 7 light riding types at Cape Town, en route to Sydney.

For several decades horses remained scarce and highly valuable. By the 1830s, however, Australia’s herd was growing steadily, as settlers imported mixed-breed horses from India and the Cape, and Thoroughbreds, Clydesdales and Arabians from England.

Explorers began using horses to traverse and chart inland Australia, and from the 1850s thousands of hopeful miners relied on horses to carry them to the booming goldfields.

Pastoral stations

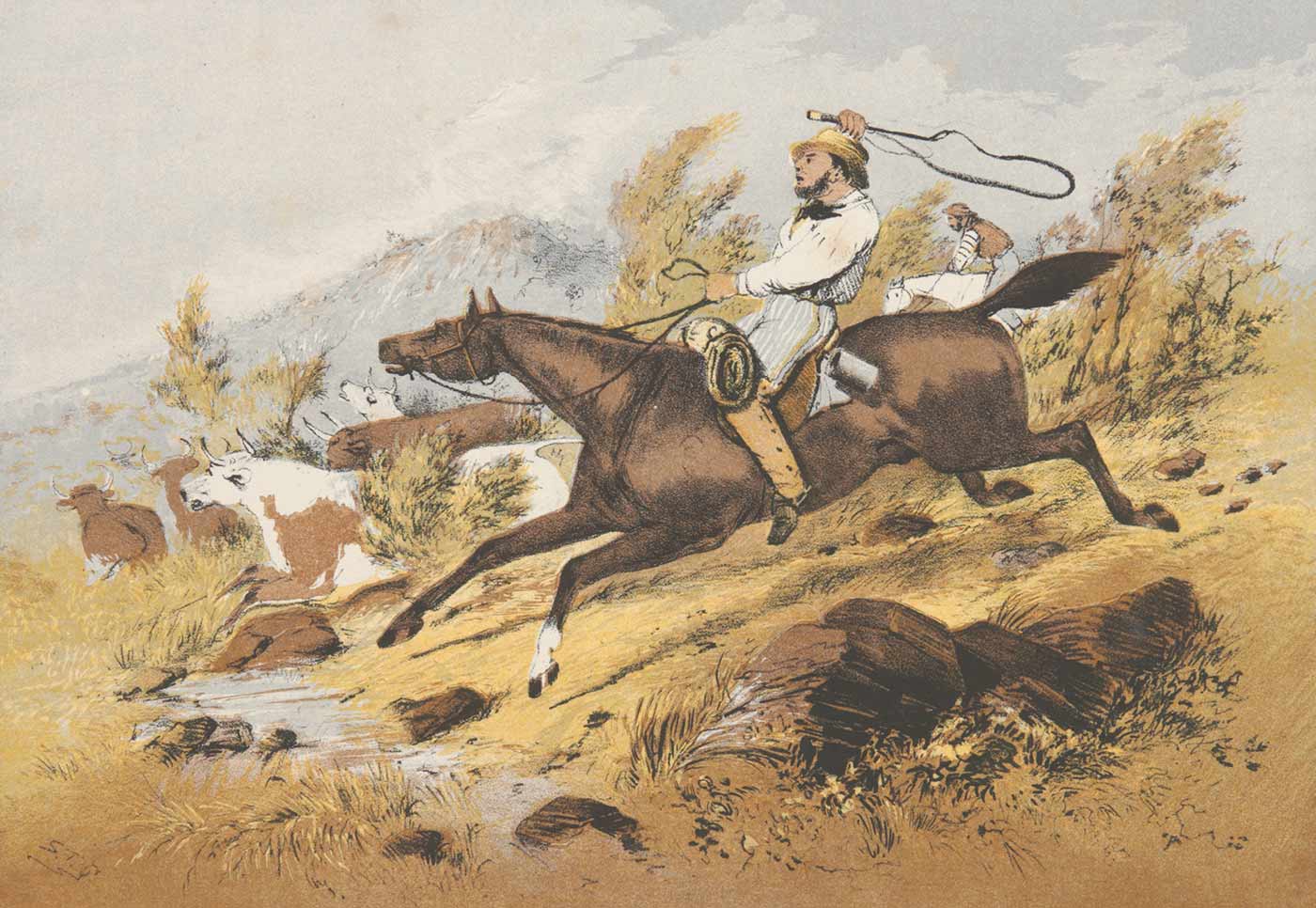

From the late 18th century European settlers, together with their sheep, cattle and horses, spread inland across the Australian continent, occupying tracts of grazing land.

On pastoral stations, horses became indispensable for moving flocks and herds across open country, mustering animals for shearing or slaughter, patrolling property boundaries and recovering lost or stolen livestock.

By the late 19th century the hard-riding, whip-cracking stockman – and his tough bush horse – had become a symbol of national identity.

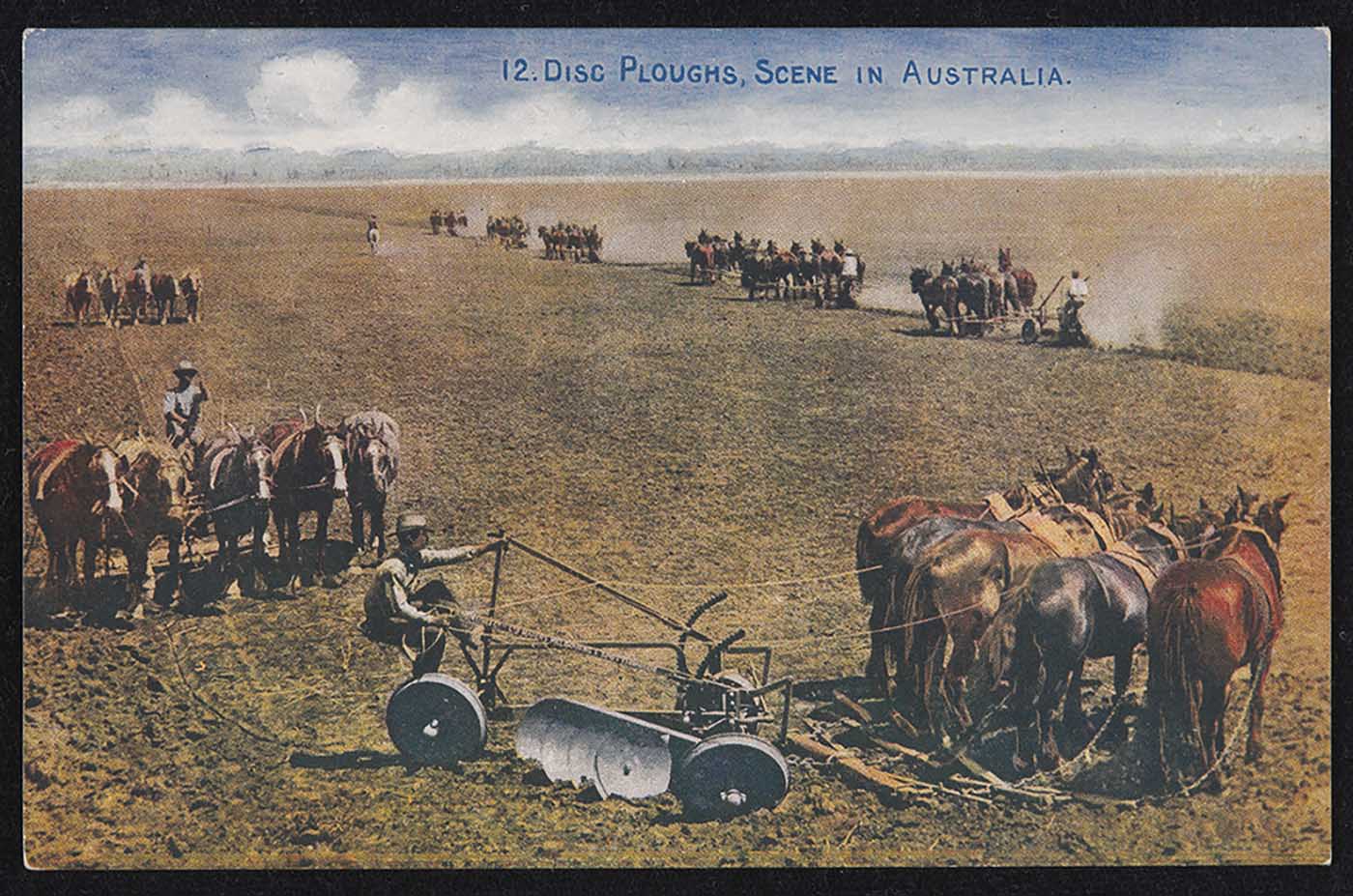

Farming horses

In the early decades of European settlement, farmers relied on people working with hand tools to plant, harvest and process crops. Horses and bullocks were in short supply, as was equipment for them to pull.

Then, from the 1830s, draught horses and lighter workhorses became increasingly available and equine muscle became the key form of power on Australian farms.

For more than a century, horses coupled to an expanding range of machines worked the land, helping to drive agricultural expansion, defining farm life and reshaping the land.

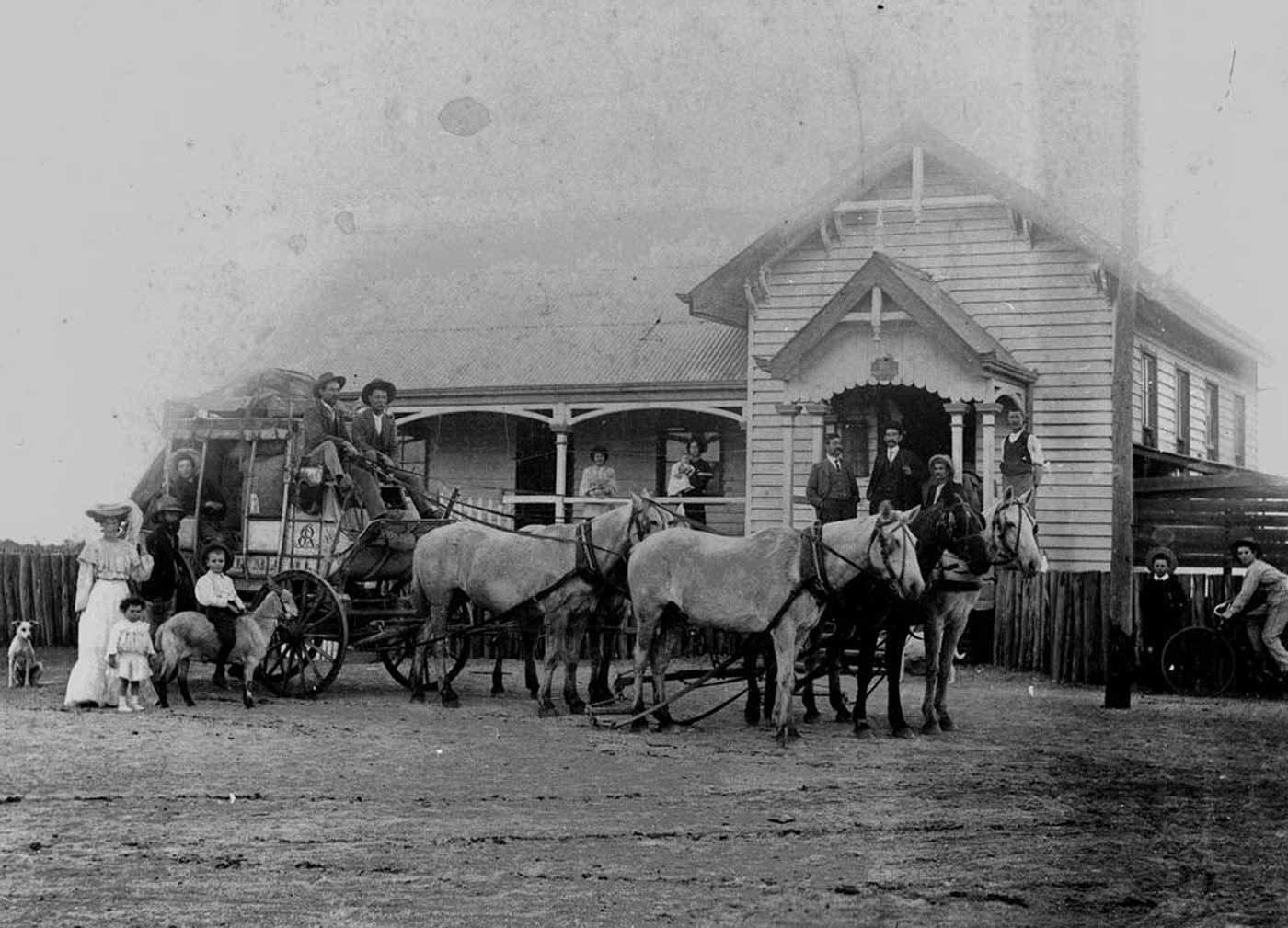

Travelling by horse

As colonial settlement expanded inland, rough tracks were built between towns, ports and remote pastoral stations.

At first most people walked or relied on bullocks to pull their loads, but as roads improved they increasingly used horses to ride, pull passenger vehicles and haul heavy goods.

While horses were expensive to buy and keep, they were faster, enabling trade to flourish, people to visit and communicate with each other, and the long arm of the law to reach across the continent.

Sale of horses

Many Australian towns grew up where drovers or teamsters stopped to water their horses and stock, or as staging posts on coaching routes.

By 1900 most main streets offered a wide range of horse-related goods and services, including blacksmiths, ironmongers, coachbuilders, saddlers and harness-makers.

There were also feed merchants, tack suppliers, agents for horsedrawn or horse-powered equipment, and mail, passenger and haulage contractors.

Working horses

At the turn of the 19th century, tens of thousands of horses lived and worked in Australia’s cities. An estimated 20,000 horses were stabled in Melbourne in the 1880s, and in the same period Sydney’s horse population supported over 50 livery stables, more than 100 saddlers and coachbuilders and over 200 carriage and buggy proprietors.

Horses hauled goods between shops, homes, factories and docks, pulled cabs, omnibuses and private vehicles, and helped with construction projects.

They also provided humans with leisure and entertainment.

Hundreds of businesses sustained the horses’ work and, as their numbers grew, civic authorities found ways to regulate their use – and clean up after them.

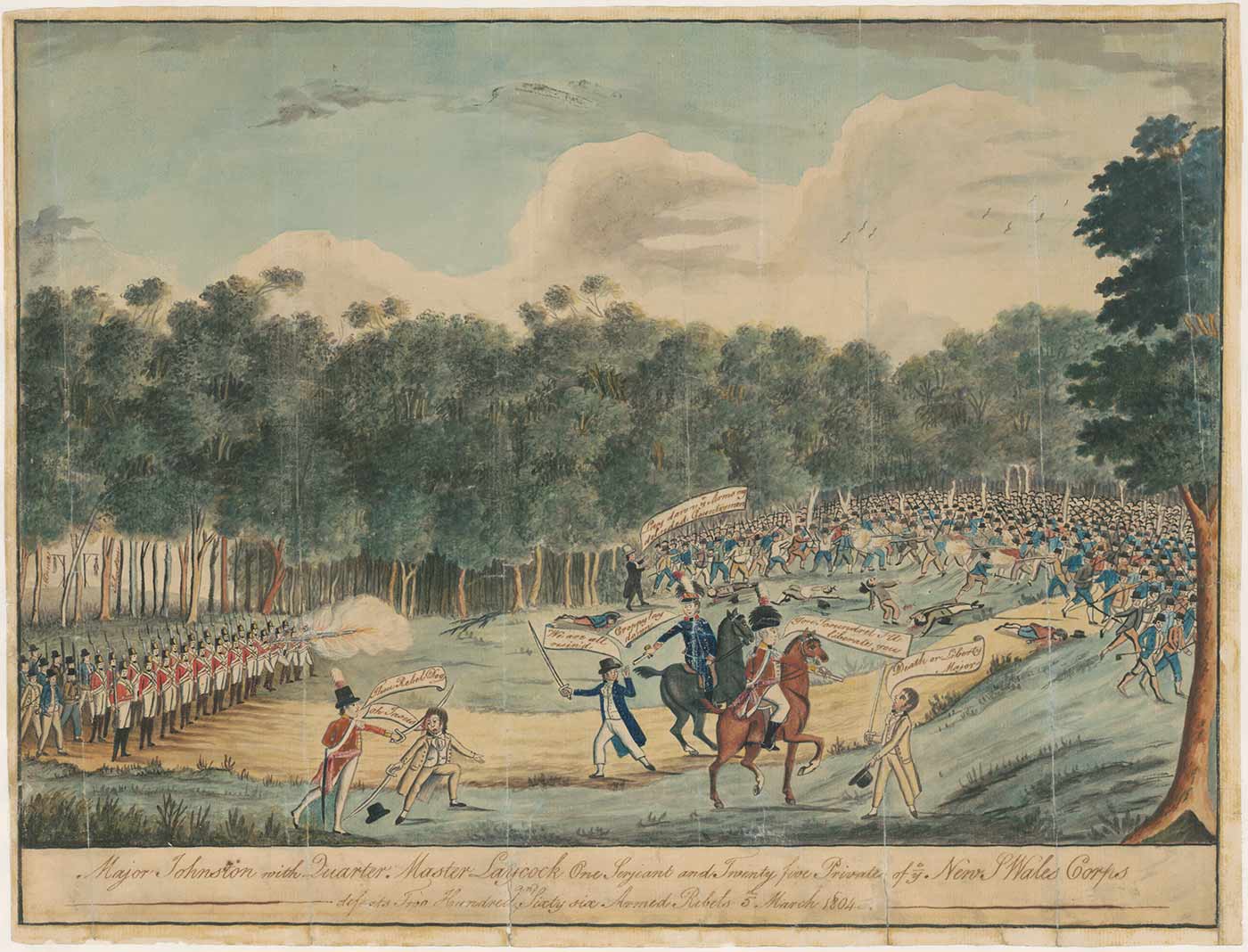

Army horses

From the 1830s to the 1940s Australian horses in their hundreds of thousands were sent to live, work and die on overseas battlefields. At first, lighter types suited as infantry remounts, as well as heavier artillery and gun horses, were sold to the British Army for allocation to British and Indian Army units in Asia and the Middle East.

The remounts, usually Thoroughbreds crossed with hard station horses carrying Arab, Timor pony and Cape horse bloodlines, became known as ‘Walers’, because the first exports were shipped from New South Wales.

Demand for quality cavalry horses also grew at home from the 1850s, as locals formed volunteer units of mounted troops. From the 1880s Australian colonial troops also took their own mounts to wars in Africa and during the First World War, Australia shipped almost 120,000 horses overseas.

Thirty thousand Australian Light Horse mounts went to the Middle East, another 80,000 horses were supplied to Indian cavalry units, and a further 10,000 were sent to haul artillery and supplies through the mud and cold of the Western Front.

The Australian Light Horseman, mounted on his Waler, became a national symbol of heroism, endurance and sacrifice.

Welfare of horses

From the mid-19th century, Australians’ concern for the health and welfare of horses mounted as these animals became more common and integral to people’s everyday lives.

Working horses often developed injuries, illnesses and disease, sometimes due to overwork, poor care or cruelty.

Some people aimed to alleviate the physical suffering of horses, in part to keep them labouring. Others were more concerned about the physical and emotional wellbeing of horses, believing they deserved kind treatment and a happy life.

More recently, activists have fostered public debate about horses being involved in activities such as racing, jumping, rodeo and other high-performance sports.

Noxious trades

A host of businesses took care of the collection, disassembly and recycling of horses’ bodies. They were known, collectively, as the ‘noxious trades’ because of the foul smells and waste products generated during slaughter and from rotting carcasses, boiled down hooves and burned bones.

Initially these trades were located near city centres, reducing transport costs for the collection of live horses and the recovery of dead ones. By the early 20th century, however, residents were calling for their relocation to outlying suburbs.

Riding sports

From the 19th century mounted overlanders drove thousands of sheep and cattle to new stations across central and northern Australia. On these vast, isolated properties, flocks and herds roamed semi-wild over the open rangelands, and to manage them, stockworkers, including many Aboriginal men and women, developed distinctive kinds of horses and styles of riding.

Friendly rivalries over who was best at everyday tasks like mustering, horse breaking, and droving developed over time into the sports of campdrafting, rodeo and endurance riding.

Influenced by similar competitions in the United States of America, by the mid-20th century these sports had become codified, and today attract thousands of competitors from across Australia.

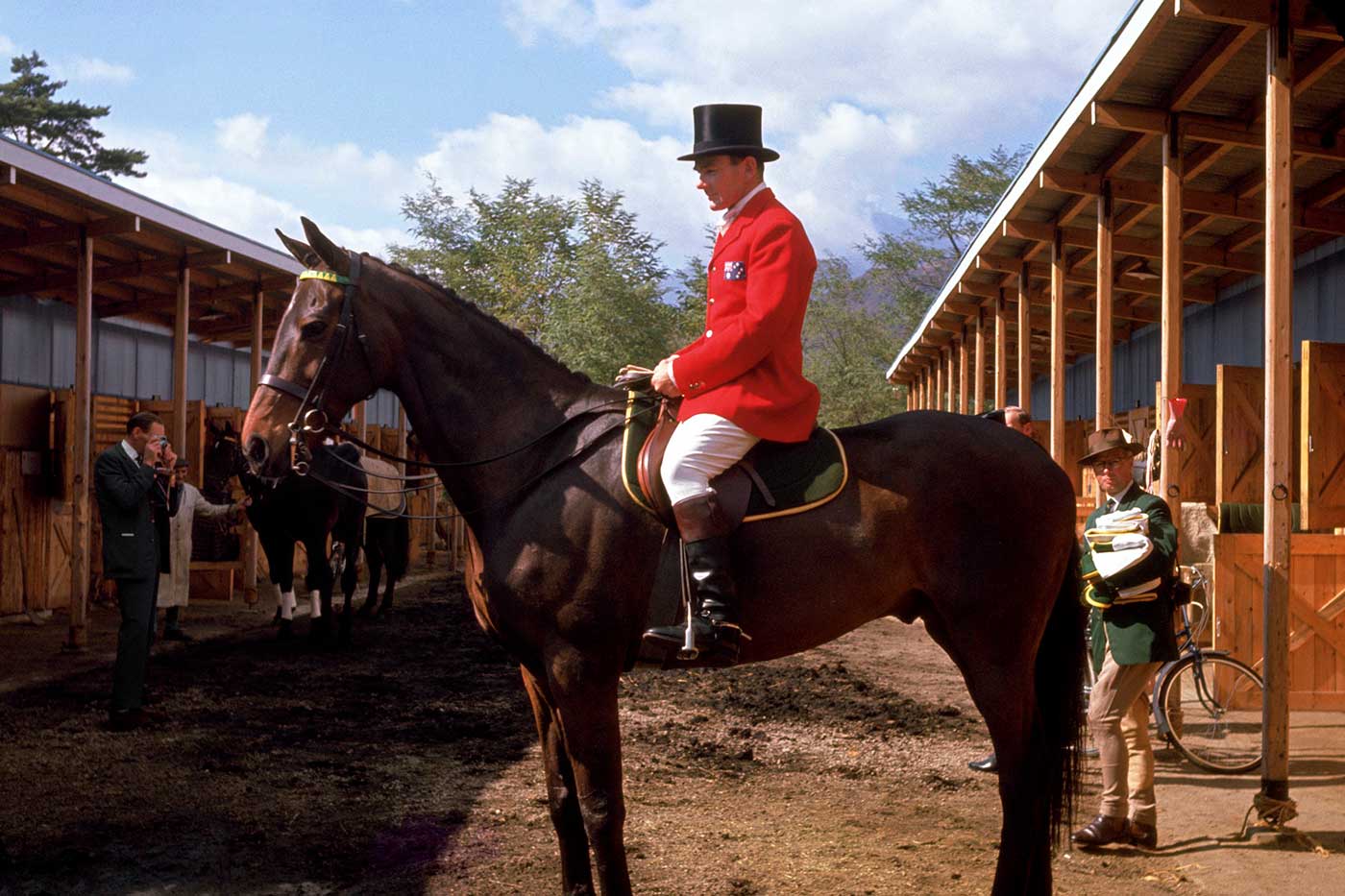

Dressage

Australian horsemen and women have always competed to test their knowledge, courage and skill, and their horses’ training, ability and quality. From the 1820s agricultural shows offered riding, driving and breed classes. Team field sports, cross-country riding tests and circus acts featuring performing horses soon followed.

Today these events have developed into organised sports such as showing, carriage driving, polocrosse, hunting and vaulting. Australian equestrians and their horses participate at the highest levels of international competition. In 2014 riders have claimed 6 gold, 3 silver and 2 bronze Olympic medals, all in eventing.

Humans and horses

People (Homo sapiens sapiens) and horses (Equus ferus caballus) have lived together for thousands of years.

At first, people hunted and herded horses for food, but around 6,500 years ago they began riding horses and using them to pull loads. Horses have derived food, care and safety from humans, and humans have benefited from horses’ strength, speed and grace.

Along the way, people have endeavoured to understand, communicate with and influence equine companions, often coming to love them in the process. But how do horses think and feel about us?

Explore more Spirited: Australia's Horse Story

You may also like