Sand, seed, hair and paint

An introduction to Papunya Painting by Michael Pickering, Director of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Program at the National Museum of Australia.

We enter the exhibition space. Immediately before us extends a magnificent gallery, with spectacular artworks from Central Australia.

Paintings of impressive scale and full of colour, complemented by careful design and lighting that show them to their full advantage.

This National Museum of Australia exhibition is a comfortable space where we can walk, pause, possibly even sit and contemplate the scale and beauty of the designs before us. We admire the works and appreciate how they are aesthetically contextualised through the design of this gallery.

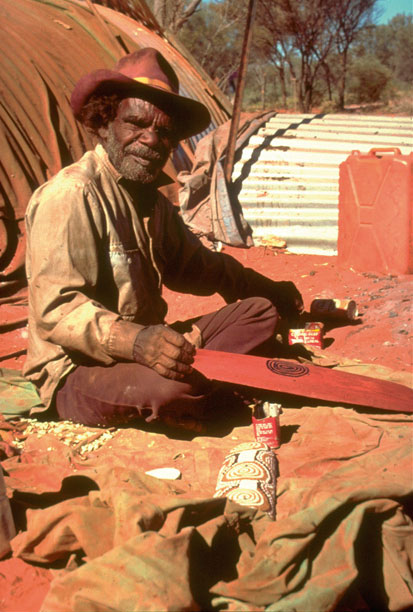

This scene, however, is but a small part of the story. Imagine the Central Australian desert — somewhere in time. A desert defined by meteorological criteria rather than by a sparseness of animals and plants. A clear blue sky. A distant and all encompassing horizon.

Maybe an isolated cloud or hill. Red sand, spinifex, grasses, and the occasional shrub and tree. In the middle of the scene there is a four-wheel drive surrounded by canvas-wrapped mattresses and camping equipment. A fire burns with a large cooling billy of tea off to one side.

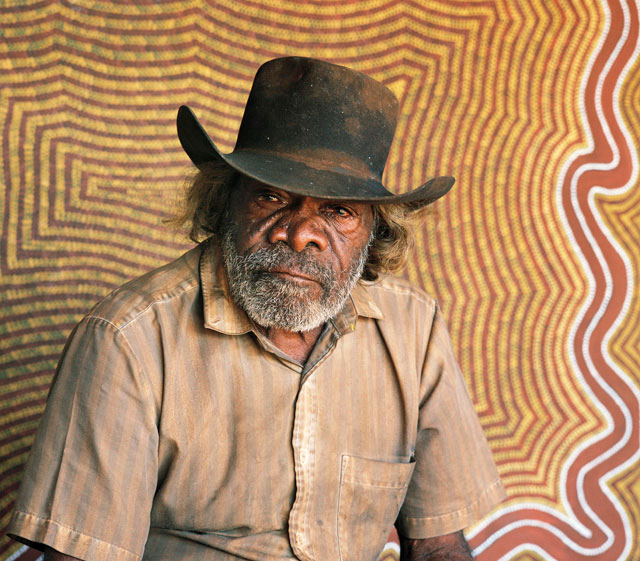

Further over, a group of men sit in a huddle. In front of them lies a large sheet of canvas.

The senior artist sits on the canvas, working directly onto the surface in front of him. Occasionally a song is sung.

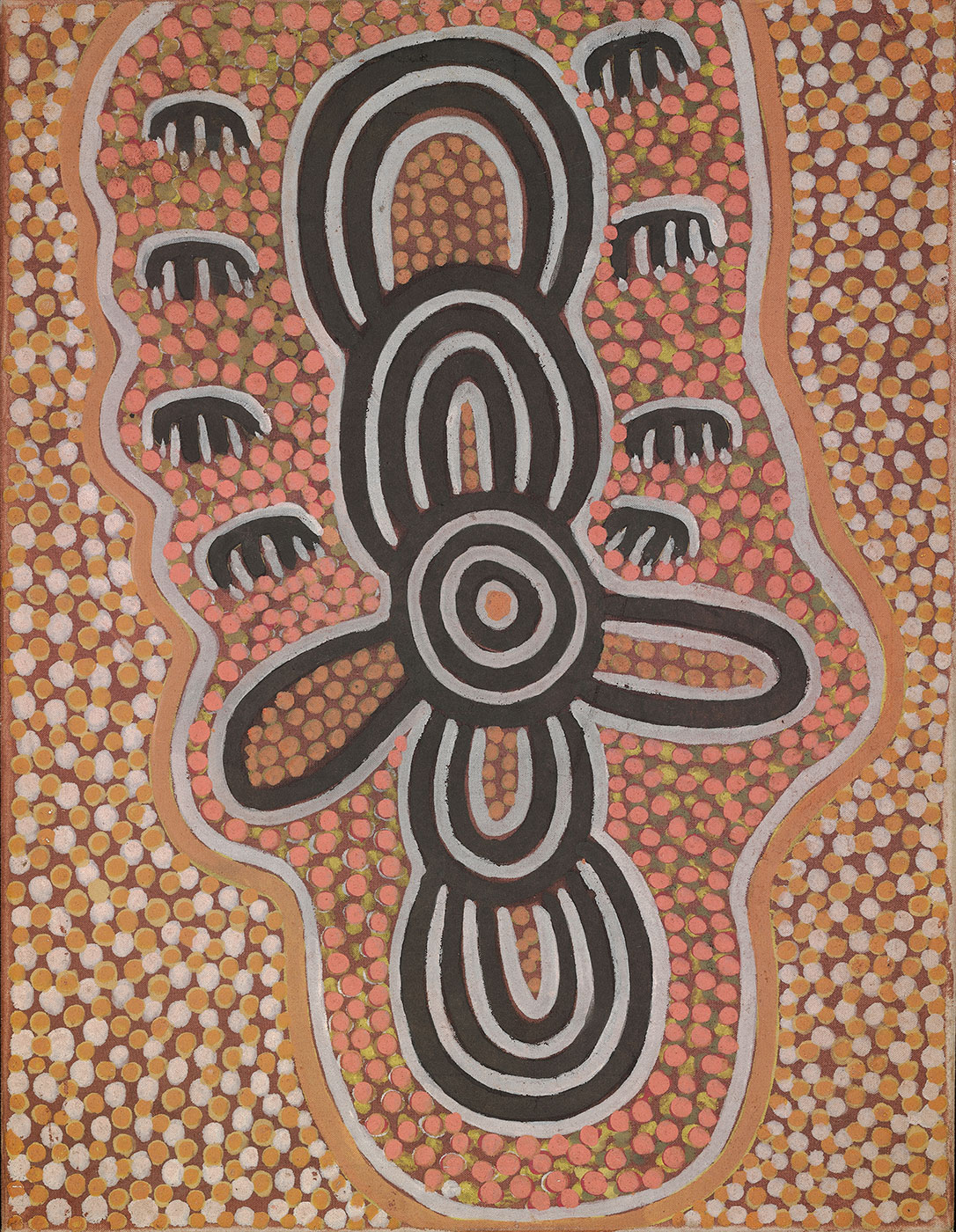

Their brushes dip into the acrylic paints and they work their way across the canvas — dots, lines, footprints and circles — all gradually coming together in a form that will be recognisable to the gallery visitor in years to come.

The wind blows, specks of sand drift across the canvas, seeds and fragments of grass adhere to the paint.

The artist pauses and scratches his head; a hair falls and is trapped in the paint, like an insect in amber. Thirty-five years later, someone looking closely at the canvas comments that it is a shame it has so much foreign material caught in it.

For many people entering the exhibition space the first impact is of the familiar. The designs on the wall reflect designs that now surround us in our day-to-day lives.

The dot patterning has become identified with Australia. Papunya-style art has become 'nationalised' and is to be found on pens, cups, diaries, calendars and clothing. It hangs on office and shop walls. It is sometimes broadcast through the media as a backdrop to unrelated topics. It is produced by people with no historical or cultural affiliation to the original artists.

Few people, however, are aware of the history and culture behind the development of this signature design style. That is where this exhibition comes into its own as we revisit the origins of the Papunya movement through reference to a very special collection.

This exhibition at the National Museum in Canberra is about an important 'school' of Australian art — one that deserves international recognition. More significantly, it is about how stories of people's lives, histories and cultures can be expressed and mediated through their art.

These works are, quite literally, historical documents, even if the ‘alphabet’ and ‘grammar’ — the lines, dots, circles, and prints — are new or unusual to a viewer.

For the National Museum of Australia, this is a significant and exciting aspect of these works.

The challenge for the Museum is to show how the works’ significance extends beyond the aesthetic to tell us about the lives, spiritual and secular beliefs, world views, iconography and aspirations of the artists.

There are many stories to be told here. Indeed, it is doubtful whether any curator or contributor would agree what the single most important aspect of the exhibition is.

We can look at the works and consider their artistic merit. We can see them as the first products of an artificially conceived commercial art industry and the issues associated with its emergence and independence.

Alternatively, we can focus on the cultural phenomena manifested in the works: the ancestral stories they relate, the cultural landscapes they describe, the religious and social relationships between the artists and their assistants, and the iconographic devices used to construct and communicate the stories.

No less significant are the stories of the relationships between the art advisers, the artists and their families.

The exhibition catalogue expands on this list. We are particularly fortunate that the authors largely write from their own experiences.

As well as illuminating the history of the works on display, these personal stories and opinions compel us to revisit our own preconceptions about the history of the Papunya art movement, as well as its significance to the artists who participated in it.

Exhibitions like this are an intellectual challenge for any museum. Such a large exhibition of predominantly two-dimensional works on canvas would normally be seen to be the exclusive domain of art galleries.

Museums are traditionally expected to concentrate on ‘the artefact’. This exhibition, however, clearly challenges that preconception, by presenting stories, imagery and objects that position the works as objects of mediation.

We first look at the works, becoming comfortable with the structure of design, imagery and aesthetic value, and then we move to look through the works to access the rich and interwoven historical and cultural narratives that lie behind their genesis.

The process of exhibition delivery is a logistical challenge. What the visitor sees is just the tip of the iceberg.

The Papunya Paintings exhibition involves staff from inside and outside the Museum, including curators, Aboriginal community members, expert contributors and advisers, collection management staff, conservators, exhibition teams, educators, publications, administration and visitor services staff amongst many others. All are contributors to the exhibition’s success.

This is an important exhibition. Our hope is that while some exhibition visitors, or readers of this volume, will come out thinking ‘I did like that bit’ and others will come out thinking ‘I didn’t like that bit’, all will come away thinking ‘I didn’t know that’.

Look closely at the works, explore their structure and investigate their meaning. But, importantly, look also for the sand, the seeds and the trapped hair. Those little touches of both person and place are just a small part of what makes these works more than just art.

This text is an extract from Papunya Painting: Out of the Desert exhibition catalogue.

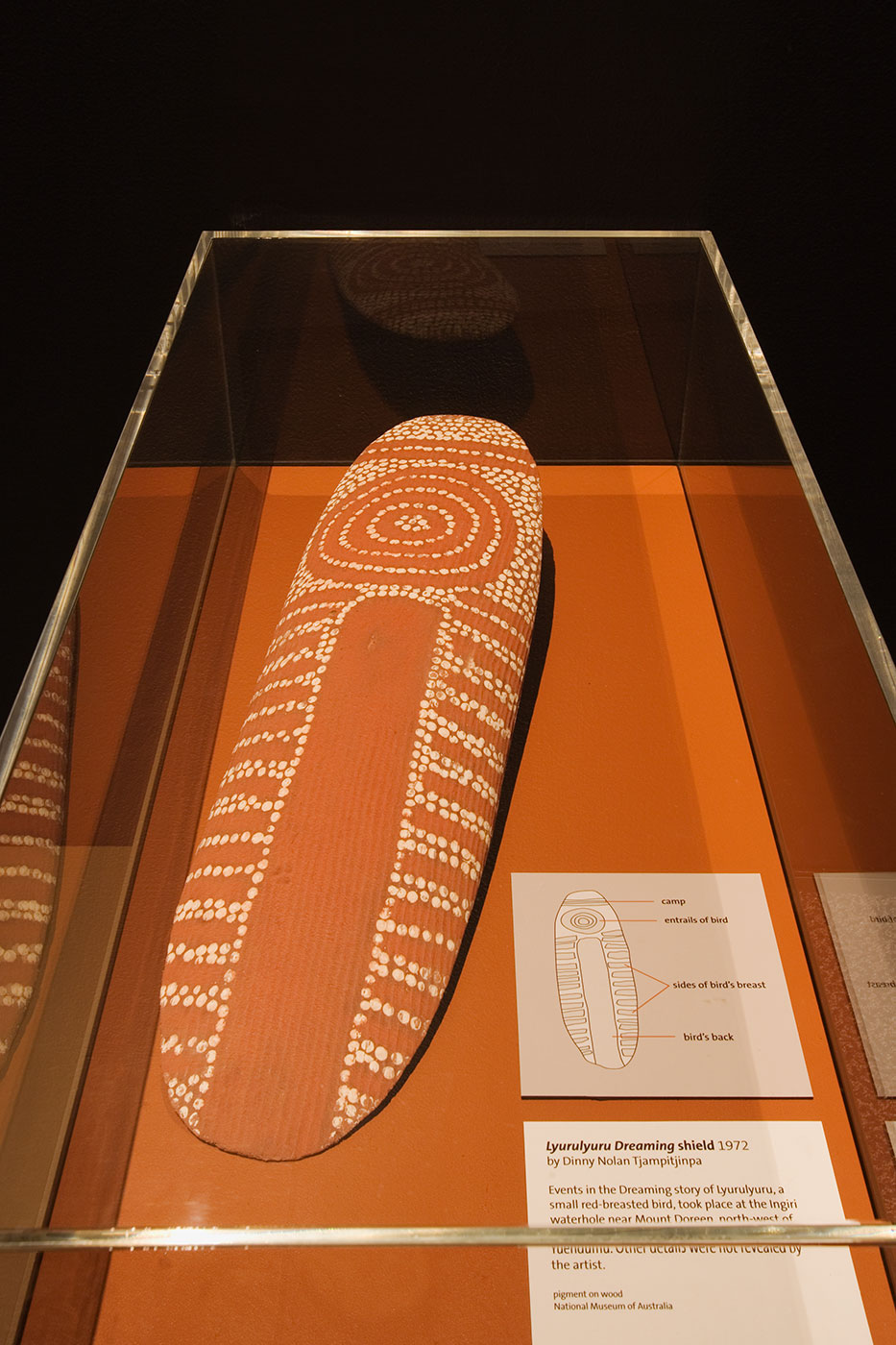

The Papunya Painting exhibition, on show at the National Museum in Canberra from 28 November 2007 to 3 February 2008, included many works on canvas, carvings and other objects. All works are part of the National Museum of Australia collection unless otherwise stated.

All photography is by Lannon Harley and George Serras, unless otherwise stated.

All works are copyright the artists or their estates and are licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency 2007. They must not be reproduced in any form without permission.

Explore more on PAPUNYA PAINTING